1.

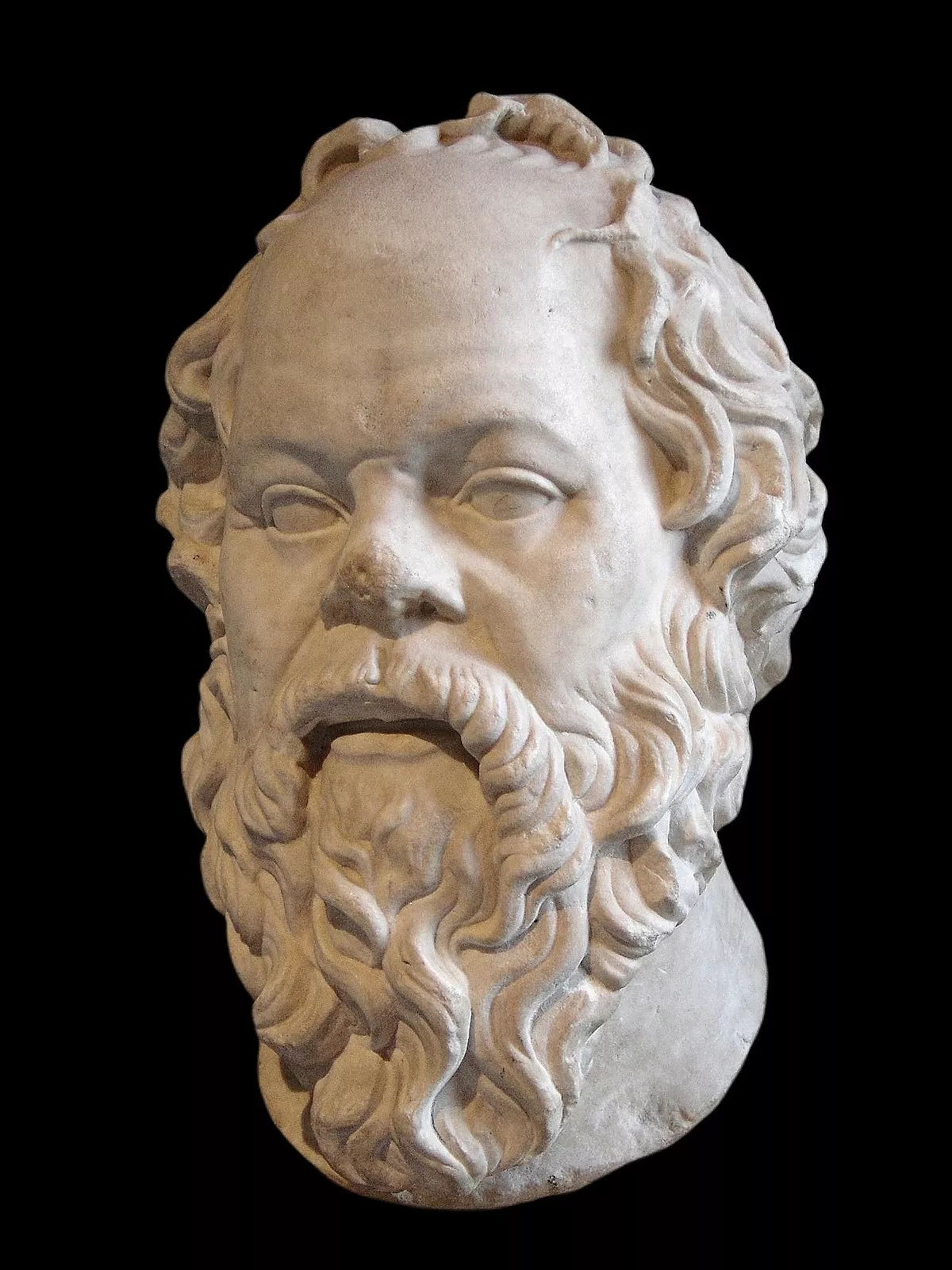

1. Socrates was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought.

1.

1. Socrates was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought.

An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no texts and is known mainly through the posthumous accounts of classical writers, particularly his students Plato and Xenophon.

Contradictory accounts of Socrates make a reconstruction of his philosophy nearly impossible, a situation known as the Socratic problem.

Socrates spent his last day in prison, refusing offers to help him escape.

Plato's dialogues are among the most comprehensive accounts of Socrates to survive from antiquity.

The Platonic Socrates lends his name to the concept of the Socratic method, and to Socratic irony.

Socrates is known for proclaiming his total ignorance; he used to say that the only thing he was aware of was his ignorance, seeking to imply that the realization of one's ignorance is the first step in philosophizing.

Socrates exerted a strong influence on philosophers in later antiquity and has continued to do so in the modern era.

Socrates was studied by medieval and Islamic scholars and played an important role in the thought of the Italian Renaissance, particularly within the humanist movement.

Socrates admired Socrates for his intelligence, patriotism, and courage on the battlefield.

In Memorabilia, he defends Socrates from the accusations of corrupting the youth and being against the gods; essentially, it is a collection of various stories gathered together to construct a new apology for Socrates.

Plato was a pupil of Socrates and outlived him by five decades.

How trustworthy Plato is in representing the attributes of Socrates is a matter of debate; the view that he did not represent views other than Socrates's own is not shared by many contemporary scholars.

Xenophon's Socrates is duller, less humorous and less ironic than Plato's.

Aristophanes's most important comedy with respect to Socrates is The Clouds, in which Socrates is a central character.

Aristotle was not a contemporary of Socrates; he studied under Plato at the latter's Academy for twenty years.

Furthermore, Xenophon was biased in his depiction of his former friend and teacher: he believed Socrates was treated unfairly by Athens, and sought to prove his point of view rather than to provide an impartial account.

Socrates was born in 470 or 469 BC to Sophroniscus and Phaenarete, a stoneworker and a midwife, respectively, in the Athenian deme of Alopece; therefore, he was an Athenian citizen, having been born to relatively affluent Athenians.

Socrates lived close to his father's relatives and inherited, as was customary, part of his father's estate, securing a life reasonably free of financial concerns.

Socrates learned the basic skills of reading and writing and, like most wealthy Athenians, received extra lessons in various other fields such as gymnastics, poetry and music.

Socrates was married twice : his marriage to Xanthippe took place when Socrates was in his fifties, and another marriage was with a daughter of Aristides, an Athenian statesman.

Socrates fulfilled his military service during the Peloponnesian War and distinguished himself in three campaigns, according to Plato.

Again Socrates was the sole abstainer, choosing to risk the tyrants' wrath and retribution rather than to participate in what he considered to be a crime.

Socrates attracted great interest from the Athenian public and especially the Athenian youth.

Socrates was notoriously ugly, having a flat turned-up nose, bulging eyes and a large belly; his friends joked about his appearance.

Socrates was indifferent to material pleasures, including his own appearance and personal comfort.

Socrates neglected personal hygiene, bathed rarely, walked barefoot, and owned only one ragged coat.

Socrates died in Athens in 399 BC after a trial for impiety and the corruption of the young.

Socrates spent his last day in prison among friends and followers who offered him a route to escape, which he refused.

Socrates died the next morning, in accordance with his sentence, after drinking poison hemlock.

Socrates was found guilty by a majority vote cast by a jury of hundreds of male Athenian citizens and, according to the custom, proposed his own penalty: that he should be given free food and housing by the state for the services he rendered to the city, or alternatively, that he be fined one mina of silver.

The accusations against Socrates were initiated by a poet, Meletus, who asked for the death penalty in accordance with the charge of asebeia.

Plato's Apology starts with Socrates answering the various rumours against him that have given rise to the indictment.

Meletus responds by repeating the accusation that Socrates is an atheist.

Socrates was given the chance to offer alternative punishments for himself after being found guilty.

Socrates could have requested permission to flee Athens and live in exile, but he did not do so.

In return, Socrates warned jurors and Athenians that criticism of them by his many disciples was inescapable, unless they became good men.

Socrates's friends visited him and offered him an opportunity to escape, which he declined.

The question of what motivated Athenians to convict Socrates remains controversial among scholars.

The first is that Socrates was convicted on religious grounds; the second, that he was accused and convicted for political reasons.

In those accounts, Socrates is portrayed as making no effort to dispute the fact that he did not believe in the Athenian gods.

The non-constructivist approach holds that Socrates merely wants to establish the inconsistency between the premises and the conclusion of the initial argument.

Socrates starts his discussions by prioritizing the search for definitions.

Philosopher Peter Geach, accepting that Socrates endorses the priority of definition, finds the technique fallacious.

In some of Plato's dialogues, Socrates appears to credit himself with some knowledge, and can even seem strongly opinionated for a man who professes his own ignorance.

One explanation is that Socrates is being either ironic or modest for pedagogical purposes: he aims to let his interlocutor to think for himself rather than guide him to a prefixed answer to his philosophical questions.

Socrates is known for disavowing knowledge, a claim encapsulated in the saying "I know that I know nothing".

Whether Socrates genuinely thought he lacked knowledge or merely feigned a belief in his own ignorance remains a matter of debate.

Lesher suggests that although Socrates claimed that he had no knowledge about the nature of virtues, he thought that in some cases, people can know some ethical propositions.

Socrates's irony is so subtle and slightly humorous that it often leaves the reader wondering if Socrates is making an intentional pun.

The story begins when Socrates is meeting with Euthyphro, a man who has accused his own father of murder.

When Socrates first hears the details of the story, he comments, "It is not, I think, any random person who could do this [prosecute one's father] correctly, but surely one who is already far progressed in wisdom".

When Euthyphro boasts about his understanding of divinity, Socrates responds that it is "most important that I become your student".

Socrates is commonly seen as ironic when using praise to flatter or when addressing his interlocutors.

In Vlastos's view, Socrates's words have a double meaning, both ironic and not.

Vlastos suggests that Socrates is being ironic when he says he has no knowledge ; while, according to another sense of "knowledge", Socrates is serious when he says he has no knowledge of ethical matters.

Some argue that Socrates thought that virtue and eudaimonia are identical.

Moral intellectualism refers to the prominent role Socrates gave to knowledge.

Socrates believed that all virtue was based on knowledge.

Socrates believed that humans were guided by the cognitive power to comprehend what they desire, while diminishing the role of impulses.

In Plato's Protagoras, Socrates implies that "no one errs willingly", which has become the hallmark of Socratic virtue intellectualism.

Whether Socrates was a practicing man of religion or a 'provocateur atheist' has been a point of debate since ancient times; his trial included impiety accusations, and the controversy has not yet ceased.

Socrates discusses divinity and the soul mostly in Alcibiades, Euthyphro, and Apology.

Socrates argued that the gods were inherently wise and just, a perception far from traditional religion at that time.

Socrates thought that goodness is independent from gods, and gods must themselves be pious.

Socrates affirms a belief in gods in Plato's Apology, where he says to the jurors that he acknowledges gods more than his accusers.

Socrates believed in oracles, divinations and other messages from gods.

Socrates then deduces that the creator should be omniscient and omnipotent and that it created the universe for the advance of humankind, since humans naturally have many abilities that other animals do not.

At times, Socrates speaks of a single deity, while at other times he refers to plural "gods".

Philosophy professor Mark McPherran suggests that Socrates interpreted every divine sign through secular rationality for confirmation.

Long suggests that it is anachronistic to suppose that Socrates believed the religious and rational realms were separate.

In Protagoras, Socrates argues for the unity of virtues using the example of courage: if someone knows what the relevant danger is, they can undertake a risk.

Socrates the elder thought that the end of life was knowledge of virtue, and he used to seek for the definition of justice, courage, and each of the parts of virtue, and this was a reasonable approach, since he thought that all virtues were sciences, and that as soon as one knew [for example] justice, he would be just.

In Gorgias, Socrates claims he was a dual lover of Alcibiades and philosophy, and his flirtatiousness is evident in Protagoras, Meno and Phaedrus.

However, the exact nature of his relationship with Alcibiades is not clear; Socrates was known for his self-restraint, while Alcibiades admits in the Symposium that he had tried to seduce Socrates but failed.

The Socratic theory of love is mostly deduced from Lysis, where Socrates discusses love at a wrestling school in the company of Lysis and his friends.

In Symposium, Socrates argues that children offer the false impression of immortality to their parents, and this misconception yields a form of unity among them.

Classicist Armand D'Angour has made the case that Socrates was in his youth close to Aspasia, and that Diotima, to whom Socrates attributes his understanding of love in Symposium, is based on her; however, it is possible that Diotima really existed.

Socrates obeyed the rules and carried out his military duty by fighting wars abroad.

Socrates's dialogues make little mention of contemporary political decisions, such as the Sicilian Expedition.

Socrates spent his time conversing with citizens, among them powerful members of Athenian society, scrutinizing their beliefs and bringing the contradictions of their ideas to light.

Socrates believed he was doing them a favor since, for him, politics was about shaping the moral landscape of the city through philosophy rather than electoral procedures.

Yet another suggestion is that Socrates endorsed views in line with liberalism, a political ideology formed in the Age of Enlightenment.

Interest in Socrates kept increasing until the third century AD.

The various schools differed in response to fundamental questions such as the purpose of life or the nature of arete, since Socrates had not handed them an answer, and therefore, philosophical schools subsequently diverged greatly in their interpretation of his thought.

Socrates was considered to have shifted the focus of philosophy from a study of the natural world, as was the case for pre-Socratic philosophers, to a study of human affairs.

Immediate followers of Socrates were his pupils, Euclid of Megara, Aristippus, and Antisthenes, who drew differing conclusions among themselves and followed independent trajectories.

The full doctrines of Socrates's pupils are difficult to reconstruct.

Socrates's school passed to his grandson, bearing the same name.

Socrates's theory was built on the pre-Socratic monism of Parmenides.

Euclid continued Socrates's thought, focusing on the nature of virtue.

For Muslim scholars, Socrates was hailed and admired for combining his ethics with his lifestyle, perhaps because of the resemblance in this regard with Muhammad's personality.

Socratic doctrines were altered to match Islamic faith: according to Muslim scholars, Socrates made arguments for monotheism and for the temporality of this world and rewards in the next life.

Bruni and Manetti were interested in defending secularism as a non-sinful way of life; presenting a view of Socrates that was aligned with Christian morality assisted their cause.

Ficino portrayed a holy picture of Socrates, finding parallels with the life of Jesus Christ.

In early modern France, Socrates's image was dominated by features of his private life rather than his philosophical thought, in various novels and satirical plays.

Michel de Montaigne wrote extensively on Socrates, linking him to rationalism as a counterweight to contemporary religious fanatics.

For Hegel, Socrates marked a turning point in the history of humankind by the introduction of the principle of free subjectivity or self-determination.

Not only did Socrates not write anything down, according to Kierkegaard, but his contemporaries misconstrued and misunderstood him as a philosopher, leaving us with an almost impossible task in comprehending Socratic thought.

Socrates was not only a subject of study for Kierkegaard, he was a model as well: Kierkegaard paralleled his task as a philosopher to Socrates.

Socrates writes, "The only analogy I have before me is Socrates; my task is a Socratic task, to audit the definition of what it is to be a Christian", with his aim being to bring society closer to the Christian ideal, since he believed that Christianity had become a formality, void of any Christian essence.

Kierkegaard denied being a Christian, as Socrates denied possessing any knowledge.

For Nietzsche, Socrates turned the scope of philosophy from pre-Socratic naturalism to rationalism and intellectualism.

Arendt, in Eichmann in Jerusalem, suggests that Socrates's constant questioning and self-reflection could prevent the banality of evil.

Socrates sees an elitist Socrates in Plato's Republic as exemplifying why the polis is not, and could not be, an ideal way of organizing life, since philosophical truths cannot be digested by the masses.

Popper takes the opposite view: he argues that Socrates opposes Plato's totalitarian ideas.