1.

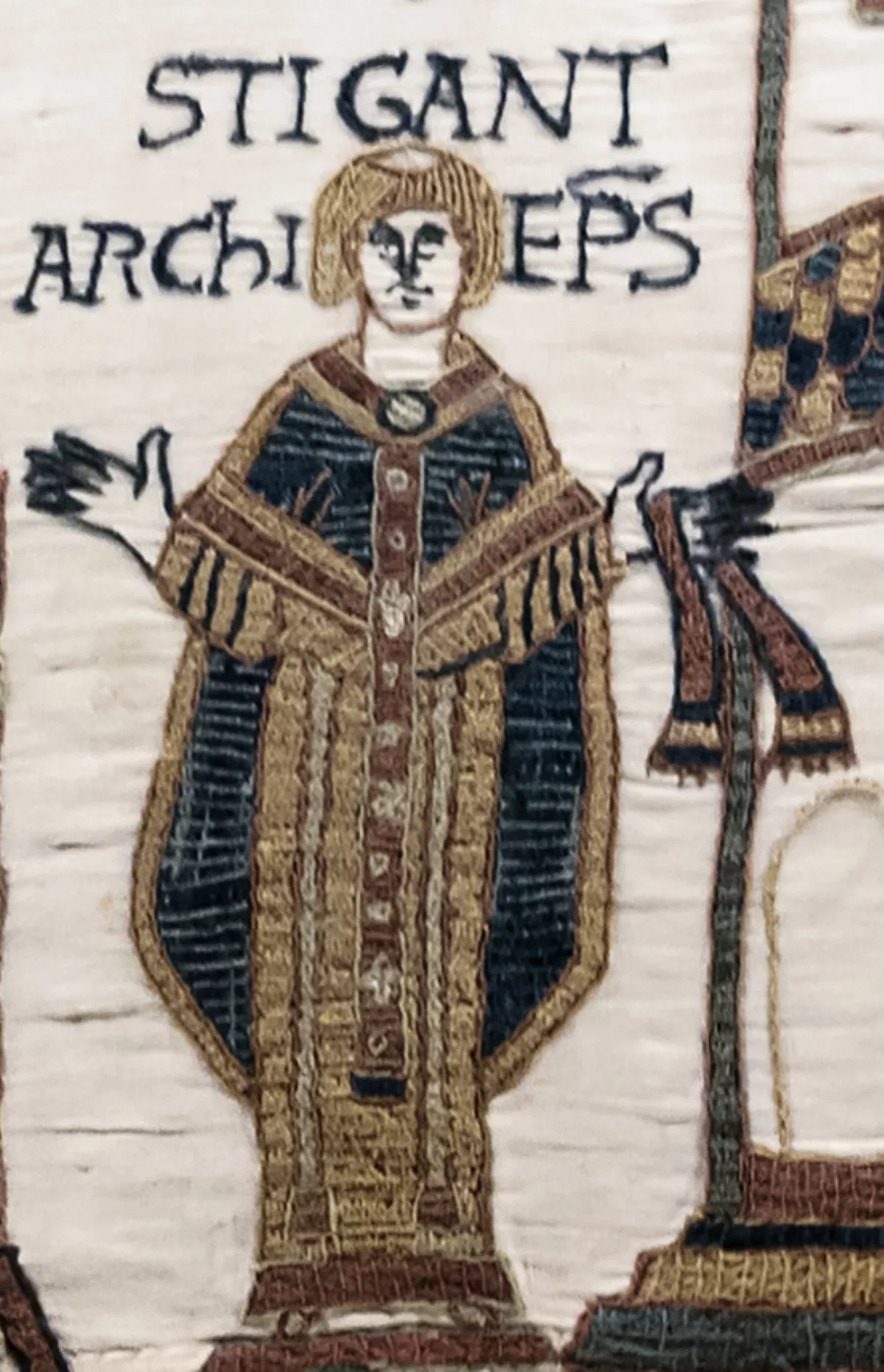

1. Stigand was an Anglo-Saxon churchman in pre-Norman Conquest England who became Archbishop of Canterbury.

1.

1. Stigand was an Anglo-Saxon churchman in pre-Norman Conquest England who became Archbishop of Canterbury.

Stigand was named Bishop of Elmham in 1043, and was later Bishop of Winchester and Archbishop of Canterbury.

Stigand was an advisor to several members of the Anglo-Saxon and Norman English royal dynasties, serving six successive kings.

Stigand served King Cnut as a chaplain at a royal foundation at Ashingdon in 1020, and as an advisor then and later.

Stigand continued in his role of advisor during the reigns of Cnut's sons, Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut.

Monastic writers of the time accused Stigand of extorting money and lands from the church, and by 1066 the only estates richer than Stigand's were the royal estates and those of Harold Godwinson.

Four years later he was appointed to the see of Winchester, and then in 1052 to the archdiocese of Canterbury, which Stigand held jointly with Winchester.

Stigand was present at the deathbed of King Edward and at the coronation of Harold Godwinson as king of England in 1066.

Stigand's excommunication meant that he could only assist at the coronation.

Stigand was born in East Anglia, possibly in Norwich, to an apparently prosperous family of mixed English and Scandinavian ancestry, as is shown by the fact that Stigand's name was Norse but his brother's was English.

Stigand's sister held land in Norwich, but her given name is unrecorded.

Stigand first appears in the historical record in 1020 as a royal chaplain to King Cnut of England.

Stigand was consecrated bishop in 1043, but later that year Edward deposed Stigand and deprived him of his wealth.

Some suspected that Stigand had urged Emma to support Magnus, and claimed that his deposition was because of this.

In 1047 Stigand was translated to the see of Winchester, but he retained Elmham until 1052.

Stigand, whether or not he was a supporter of Godwin's, did not go into exile with the earl.

Some medieval sources state that Stigand took part in the negotiations that reached a peace between the king and his earl; the Canterbury manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle calls Stigand the king's chaplain and advisor during the negotiations.

Stigand was the first non-monk to be appointed to either English archbishopric since before the days of Dunstan.

Historian Nicholas Brooks holds the view that Stigand was not excommunicated at this time, but rather was ordered to refrain from any archiepiscopal functions, such as the consecration of bishops.

Stigand argues that in 1062 papal legates sat in council with Stigand, something they would not have done had he been excommunicated.

Stigand did not travel to Rome to receive a pallium, the band worn around the neck that is the symbol of an archbishop's authority, from the pope.

Five successive popes excommunicated Stigand for holding both Winchester and Canterbury at the same time.

The medieval chronicler William of Poitiers claimed that in 1052 Stigand agreed that William of Normandy, the future William the Conqueror, should succeed King Edward.

York had long been held in common with Worcester, but during the period when Stigand was excommunicated, the see of York claimed oversight over the sees of Lichfield and Dorchester.

Stigand was allowed to attend the council they held and was an active participant with the legates in the business of the council.

Stigand was probably the most lavish clerical donor of his period when great men gave to churches on an unprecedented scale.

Between his holding of two sees and the appointment of his men to other sees in the southeast of England, Stigand was an important figure in defending the coastline against invasion.

Stigand's landholdings were spread across ten counties, and in some of those counties, his lands were larger than the king's holdings.

The English sources claim that Ealdred, the Archbishop of York, crowned Harold, while the Norman sources claim that Stigand did so, with the conflict between the various sources probably tracing to the post-Conquest desire to vilify Harold and depict his coronation as improper.

Stigand did support Harold, and was present at Edward the Confessor's deathbed.

Stigand was present at the coronation of William's queen, Matilda, in 1068, although once more the ceremony was actually performed by Ealdred.

Archbishop Stigand appears on several royal charters in 1069, along with both Norman and English leaders.

Stigand even consecrated Remigius de Fecamp as Bishop of Dorchester in 1067.

Some accounts state that Stigand did appear at the council which deposed him, but nothing is recorded of any defence that he attempted.

Besides witnessing charters and consecrating Remigius, Stigand appears to have been a member of the royal council, and able to move freely about the country.

Hugh the Chanter, a medieval chronicler, claimed that the confiscated wealth of Stigand helped keep King William on the throne.

Alexander Rumble argued that Stigand was unlucky in living past the Conquest, stating that it could be said that Stigand was "unlucky to live so long that he saw in his lifetime not only the end of the Anglo-Saxon state but the challenging of uncanonical, but hitherto tolerated, practices by a wave of papal reforms".