1.

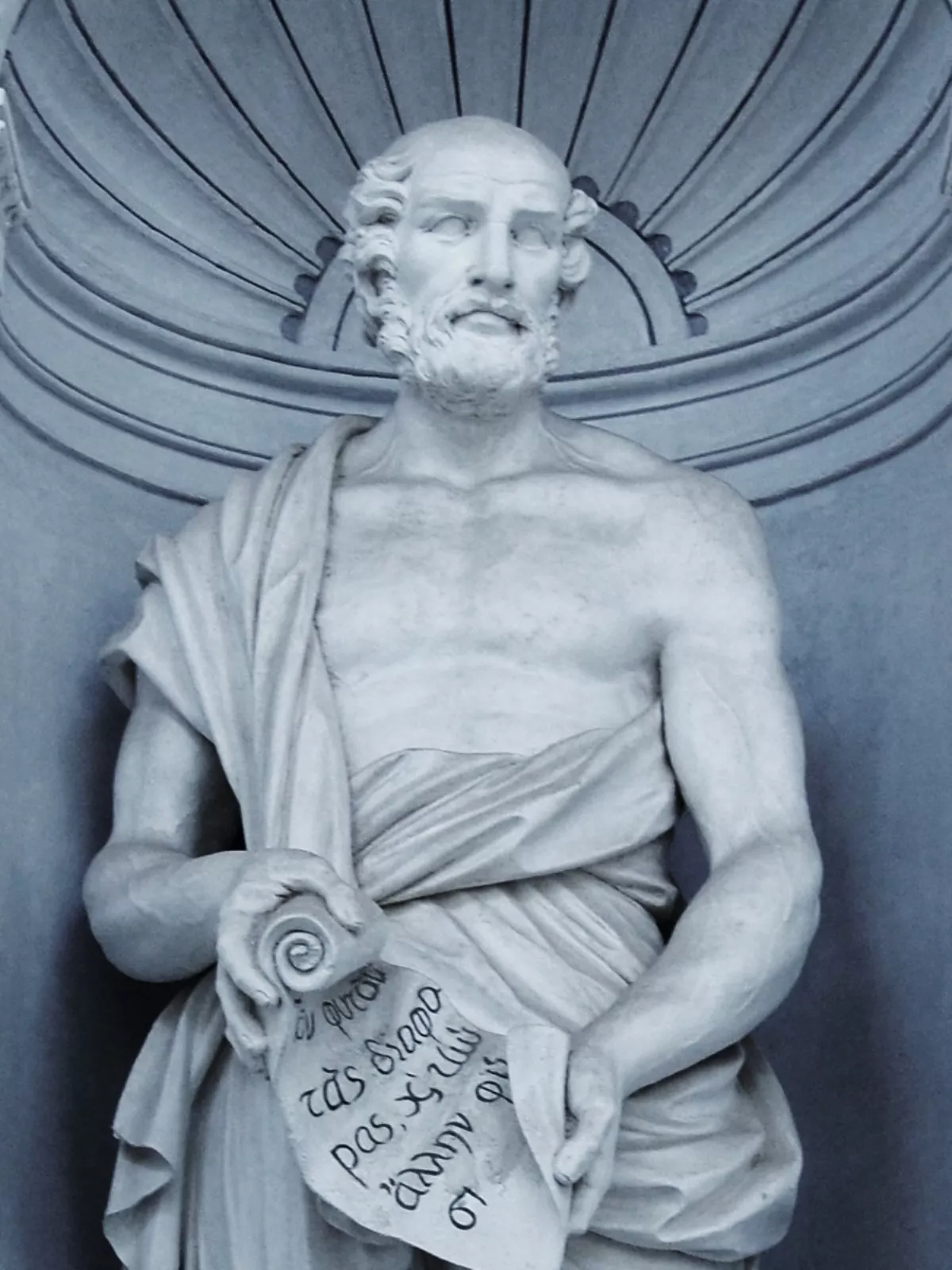

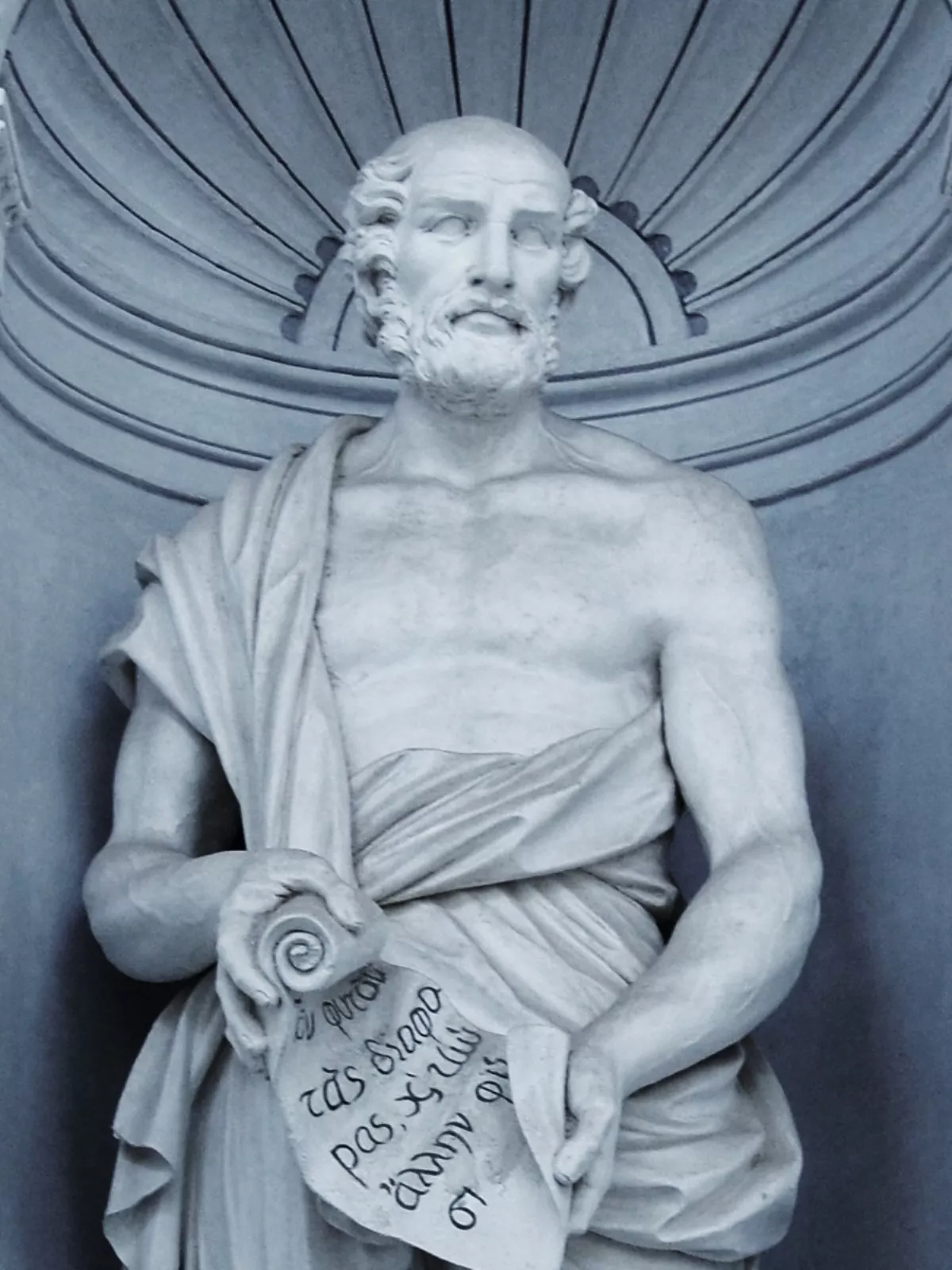

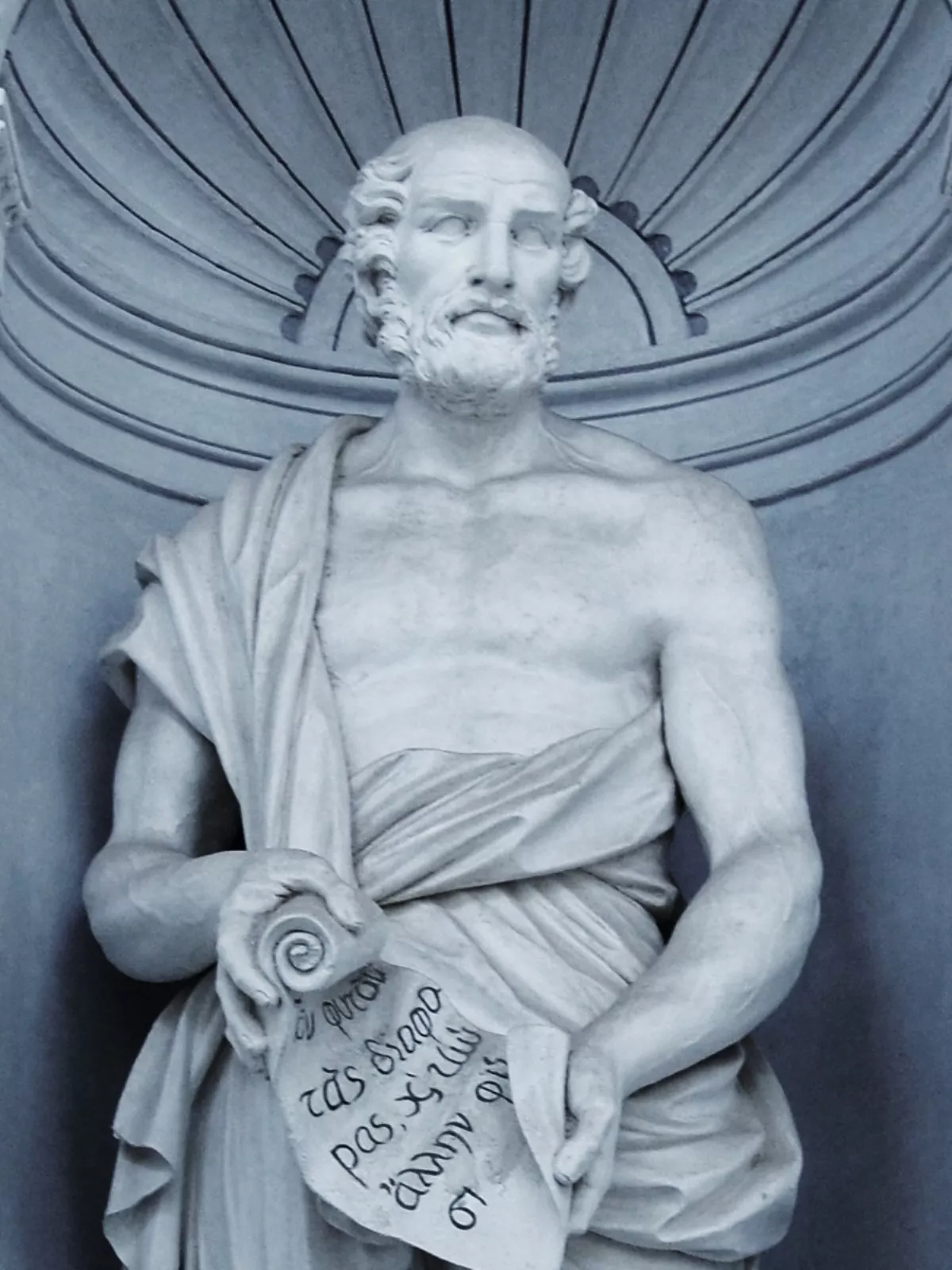

1. Theophrastus wrote numerous treatises across all areas of philosophy, working to support, improve, expand, and develop the Aristotelian system.

1.

1. Theophrastus wrote numerous treatises across all areas of philosophy, working to support, improve, expand, and develop the Aristotelian system.

Theophrastus made significant contributions to various fields, including ethics, metaphysics, botany, and natural history.

Theophrastus's given name was ; the nickname Theophrastus was reputedly given to him by Aristotle in recognition of his eloquent style.

Theophrastus came to Athens at a young age and initially studied in Plato's school.

Theophrastus presided over the Peripatetic school for thirty-six years, during which time the school flourished greatly.

Theophrastus is often considered the father of botany for his works on plants.

The interests of Theophrastus were wide ranging, including biology, physics, ethics and metaphysics.

Theophrastus's two surviving botanical works, Enquiry into Plants and On the Causes of Plants, were an important influence on Renaissance science.

Theophrastus regarded space as the mere arrangement and position of bodies, time as an accident of motion, and motion as a necessary consequence of all activity.

Around 335 BC, Theophrastus moved with Aristotle to Athens, where Aristotle began teaching in the Lyceum.

Theophrastus presided over the Peripatetic school for 35 years, and died at age 85, according to Diogenes.

Theophrastus is said to have remarked, "We die just when we are beginning to live".

Theophrastus's popularity was shown in the regard paid to him by Philip, Cassander, and Ptolemy, and by the complete failure of a charge of impiety brought against him.

Theophrastus's writing probably differed little from Aristotle's treatment of the same themes, though supplementary in details.

Theophrastus studied general history, as we know from Plutarch's lives of Lycurgus, Solon, Aristides, Pericles, Nicias, Alcibiades, Lysander, Agesilaus, and Demosthenes, which were probably borrowed from the work on Lives.

Besides these writings, Theophrastus wrote several collections of problems, out of which some things at least have passed into the Problems that have come down to us under the name of Aristotle, and commentaries, partly dialogue, to which probably belonged the Erotikos, Megacles, Callisthenes, and Megarikos, and letters, partly books on mathematical sciences and their history.

The text of these fragments and extracts is often so corrupt that there is a certain plausibility to the well-known story that the works of Aristotle and Theophrastus were allowed to languish in the cellar of Neleus of Scepsis and his descendants.

Theophrastus observed the process of germination and recognized the significance of climate to plants.

The book has been regarded by some as an independent work; others incline to the view that the sketches were written from time to time by Theophrastus, and collected and edited after his death; others, again, regard the Characters as part of a larger systematic work, but the style of the book is against this.

Theophrastus has found many imitators in this kind of writing, notably Joseph Hall, Sir Thomas Overbury, Bishop Earle, 17-century poet Samuel Butler, and Jean de La Bruyere, who translated the Characters.

Theophrastus describes different marbles; mentions coal, which he says is used for heating by metal-workers; describes the various metal ores; and knew that pumice stones had a volcanic origin.

Theophrastus knew that pearls came from shellfish, that coral came from India, and speaks of the fossilized remains of organic life.

Theophrastus considers the practical uses of various stones, such as the minerals necessary for the manufacture of glass; for the production of various pigments of paint such as ochre; and for the manufacture of plaster.

Lyngurium is described in the work of Theophrastus as being similar to amber, capable of attracting "straws and bits of wood", but without specifying any pyroelectric properties.

The extent to which Theophrastus followed Aristotle's doctrines, or defined them more accurately, or conceived them in a different form, and what additional structures of thought he placed upon them, can only be partially determined because of the loss of so many of his writings.

Theophrastus seems to have carried out still further the grammatical foundation of logic and rhetoric, since in his book on the elements of speech, he distinguished the main parts of speech from the subordinate parts, and direct expressions from metaphorical expressions, and dealt with the emotions of speech.

Theophrastus further distinguished a twofold reference of speech to things and to the hearers, and referred poetry and rhetoric to the latter.

Theophrastus wrote at length on the unity of judgment, on the different kinds of negation, and on the difference between unconditional and conditional necessity.

Theophrastus introduced his Physics with the proof that all natural existence, being corporeal and composite, requires principles, and first and foremost, motion, as the basis of all change.

Theophrastus attacked the doctrine of the four classical elements and challenged whether fire could be called a primary element when it appears to be compound, requiring, as it does, another material for its own nutriment.

Theophrastus departed more widely from Aristotle in his doctrine of motion, since on the one hand he extended it over all categories, and did not limit it to those laid down by Aristotle.

Theophrastus viewed motion, with Aristotle, as an activity, not carrying its own goal in itself, of that which only potentially exists, but he opposed Aristotle's view that motion required a special explanation, and he regarded it as something proper both to nature in general and the celestial system in particular:.

Theophrastus recognised no activity without motion, and so referred all activities of the soul to motion: the desires and emotions to corporeal motion, judgment and contemplation to spiritual motion.

Theophrastus seems, generally speaking, where the investigation overstepped the limits of experience, to have preferred to develop the difficulties rather than solve them, as is especially apparent in his Metaphysics.

Theophrastus was doubtful of Aristotle's teleology and recommended that such ideas be used with caution:.

Theophrastus did not follow the incessant attempts by Aristotle to refer phenomena to their ultimate foundations, or his attempts to unfold the internal connections between the latter, and between them and phenomena.

Theophrastus did not allow a happiness resting merely upon virtue, or, consequently, to hold fast by the unconditional value of morality.

Theophrastus was opposed to eating meat on the grounds that it robbed animals of life and was therefore unjust.

The International Theophrastus Project started by Brill Publishers in 1992.