1.

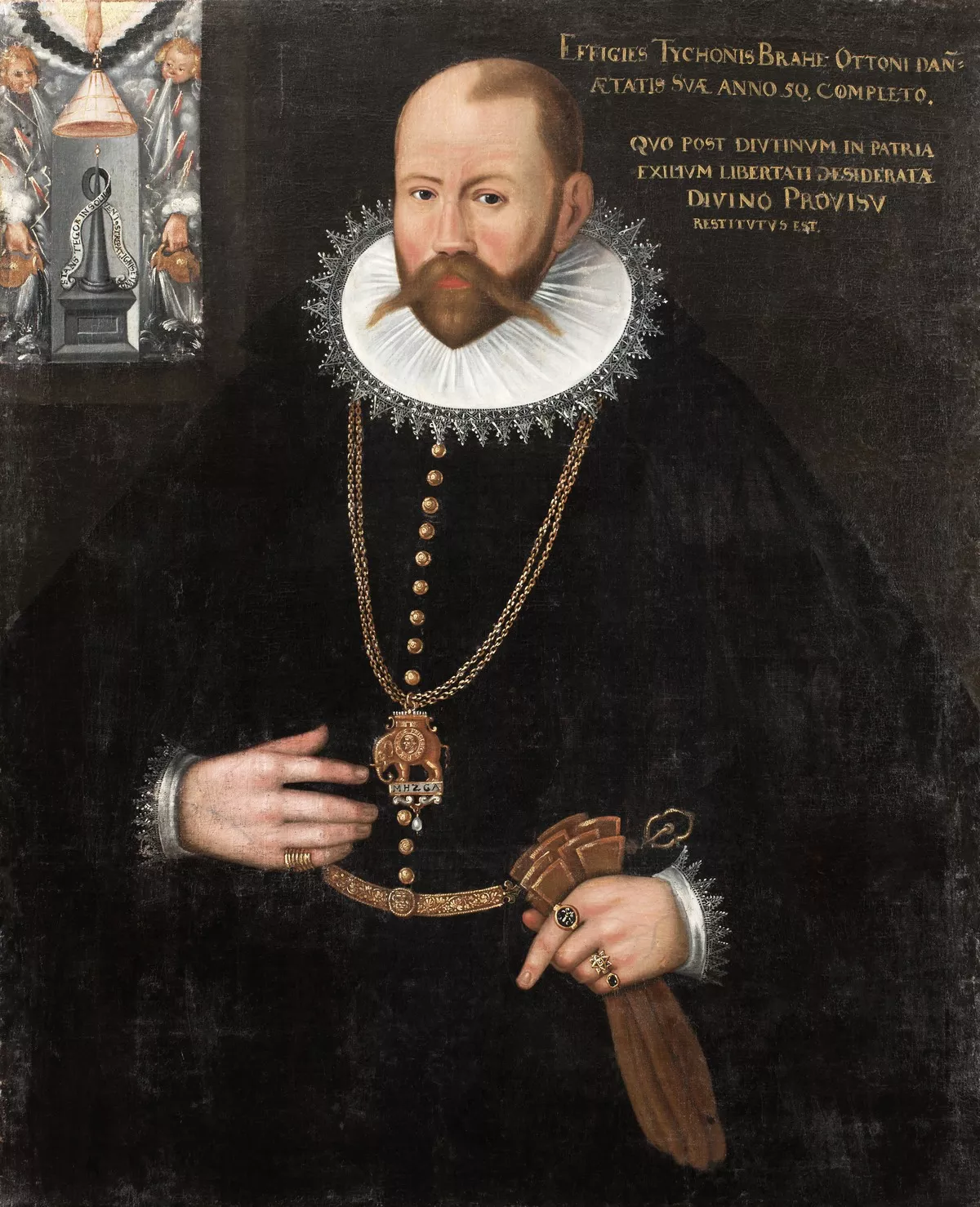

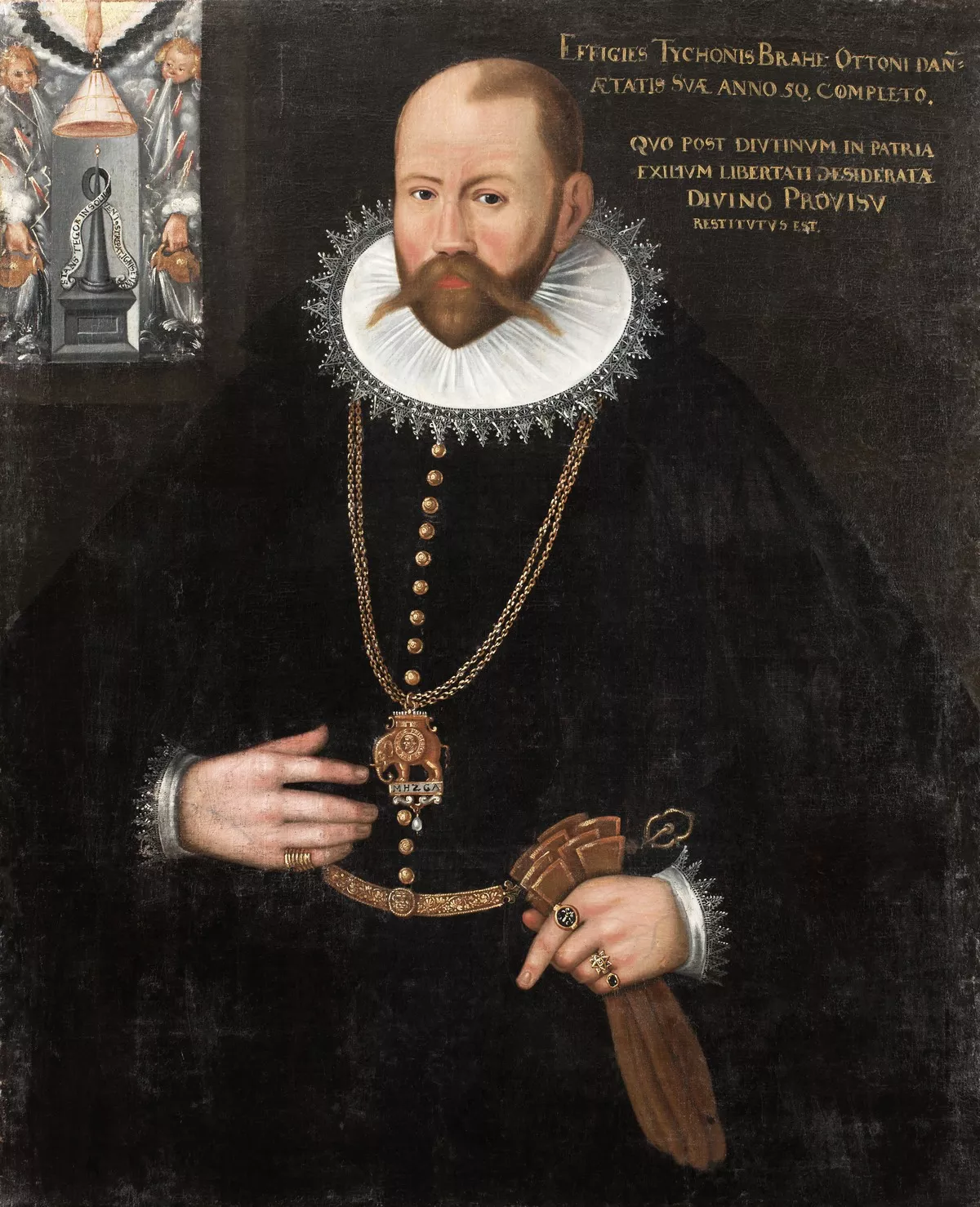

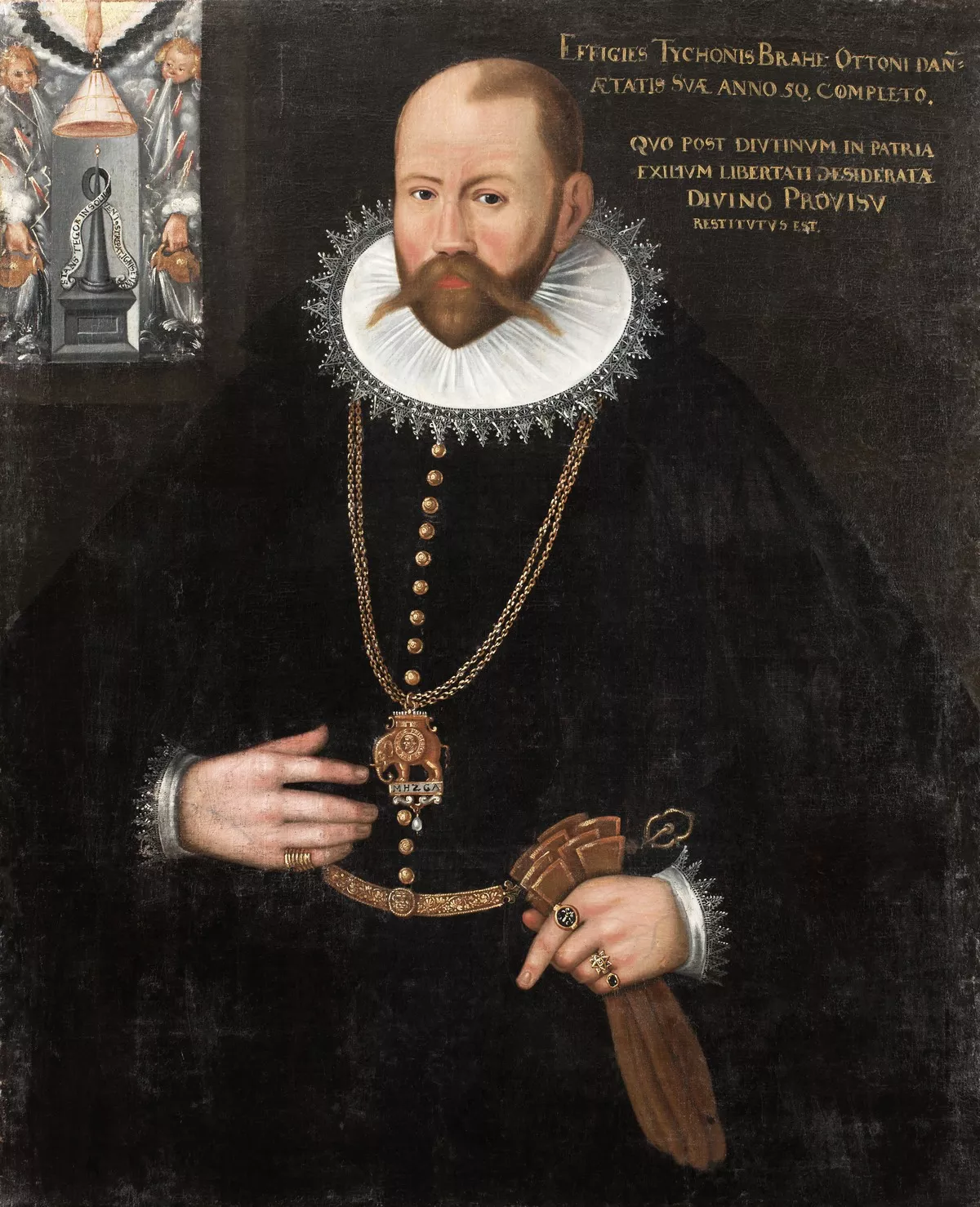

1. Tycho Brahe was known during his lifetime as an astronomer, astrologer, and alchemist.

1.

1. Tycho Brahe was known during his lifetime as an astronomer, astrologer, and alchemist.

Tycho Brahe was the last major astronomer before the invention of the telescope.

Tycho Brahe has been described as the greatest pre-telescopic astronomer.

In 1572, Tycho noticed a completely new star that was brighter than any star or planet.

Tycho Brahe later worked underground at Stjerneborg, where he realised that his instruments in Uraniborg were not sufficiently steady.

An heir to several noble families, Tycho Brahe was well educated.

Tycho Brahe worked to combine what he saw as the geometrical benefits of Copernican heliocentrism with the philosophical benefits of the Ptolemaic system, and devised the Tychonic system, his own version of a model of the Universe, with the Sun orbiting the Earth, and the planets as orbiting the Sun.

In 1597, Tycho Brahe was forced by the new king, Christian IV, to leave Denmark.

Tycho Brahe was invited to Prague, where he became the official imperial astronomer, and built an observatory at Benatky nad Jizerou.

Tycho Brahe was born as heir to several of Denmark's most influential noble families.

Tycho Brahe's parents are buried under the floor of the church of Kagerod, four kilometres west of Knutstorp Castle.

Tycho Brahe was the oldest of 12 siblings, 8 of whom lived to adulthood, including Steen Brahe and Sophia Brahe.

Tycho Brahe later wrote an ode in Latin to his dead twin, which was printed in 1572 as his first published work.

At the university, Aristotle was a staple of scientific theory, and Tycho Brahe likely received a thorough training in Aristotelian physics and cosmology.

Tycho Brahe realized that more accurate observations would be the key to making more exact predictions.

Tycho Brahe purchased an ephemeris and books on astronomy, including Johannes de Sacrobosco's, Petrus Apianus's and Regiomontanus's.

Tycho Brahe eventually talked Vedel into allowing him to pursue astronomy during the tour.

Tycho Brahe began maintaining detailed journals of all his astronomical observations.

Stories have it that he contracted pneumonia after a night of drinking with the Danish King Frederick II when the king fell into the water in a Copenhagen canal and Tycho Brahe jumped in after him.

In 1566, Tycho Brahe left to study at the University of Rostock in what is Germany.

Tycho Brahe received the best possible care at the university and wore a prosthetic nose for the rest of his life.

Tycho Brahe's father wanted him to take up law, but Tycho was allowed to travel to Rostock and then to Augsburg, where he built a great quadrant, then Basel, and Freiburg.

Soon, another uncle, Steen Bille, helped him build an observatory and alchemical laboratory at Herrevad Abbey, where Tycho was assisted by his keenest disciple, his younger sister Sophie Brahe.

Tycho Brahe was acknowledged by King Frederick II, who proposed to him that an observatory be built to better study the night sky.

Tycho Brahe was highly appreciated by King Frederick II, and he was accepted and supported by people of high social status.

The support Tycho Brahe received from the king allowed him to continue his research and make significant contributions to the field of astronomy.

Tycho Brahe began to build Uraniborg in 1576 and moved there soon after.

Tycho Brahe was a perfectionist, and by being secluded he had complete control over his research and was not limited by anyone else's restrictions, enabling him to develop innovative research.

Tycho Brahe could focus all of his energy on his work, without receiving any backlash or questioning from anyone.

Tycho Brahe compiled the most extensive and accurate catalog of stellar positions up to that time.

In 1597, Tycho Brahe moved to Prague, where he continued his work and was eventually appointed by Emperor Rudolf II in 1601 as imperial mathematician.

Kirsten and Tycho Brahe lived together for almost thirty years until Tycho Brahe's death.

However, Tycho Brahe observed that the object showed no daily parallax against the background of the fixed stars.

Tycho Brahe found that the object did not change its position relative to the fixed stars over several months, as all planets did in their periodic orbital motions, even the outer planets, for which no daily parallax was detectable.

Tycho Brahe continued with his detailed observations, often assisted by his first assistant and student, his younger sister Sophie.

In 1574, Tycho Brahe published the observations made in 1572 from his first observatory at Herrevad Abbey.

Tycho Brahe then started lecturing on astronomy, but gave it up and left Denmark in spring 1575 to tour abroad.

Tycho Brahe first visited William IV, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel's observatory at Kassel, then went on to Frankfurt, Basel, and Venice, where he acted as an agent for the Danish king, contacting artisans and craftsmen whom the king wanted to work on his new palace at Elsinore.

Tycho Brahe offered him a choice of lordships of militarily and economically important estates, such as the castles of Hammershus or Helsingborg.

Tycho Brahe was reluctant to take up a position as a lord of the realm, preferring to focus on his science.

Tycho Brahe secretly began to plan to move to Basel, wishing to participate in the burgeoning academic and scientific life there.

Tycho Brahe took control of agricultural planning, requiring the peasants to cultivate twice as much as they had done before, and he exacted corvee labor from the peasants for the construction of his new castle.

Tycho Brahe envisioned his castle Uraniborg as a temple dedicated to the muses of arts and sciences, rather than as a military fortress.

Uraniborg contained a printing press and a paper mill, both among the first in Scandinavia, enabling Tycho Brahe to publish his own manuscripts, on locally made paper with his own watermark.

Tycho Brahe created a system of ponds and canals to run the wheels of the paper mill.

Tycho Brahe was able to determine that the comet's distance to Earth was much greater than the distance of the Moon, so that the comet could not have originated in the "earthly sphere", confirming his prior anti-Aristotelian conclusions about the fixed nature of the sky beyond the Moon.

Tycho Brahe realized that the comet's tail was always pointing away from the Sun.

Tycho Brahe analyzed its motion, suggesting an orbit located between Mercury and Venus.

Pierre Gassendi wrote that Tycho Brahe had a tame elk and that his mentor the Landgrave Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel asked whether there was an animal faster than a deer.

Tycho Brahe replied that there was none, but he could send his tame elk.

When Wilhelm replied he would accept one in exchange for a horse, Tycho Brahe replied with the sad news that the elk had just died on a visit to entertain a nobleman at Landskrona.

Tycho Brahe gave gold coins to the ferryman and to the builders and workers at Tycho's paper mill.

Tycho Brahe inquired about other astronomers' observations and shared his own technological advances to help them achieve more accurate observations.

Prominent among them were John Craig, a Scottish physician who was a strong believer in the authority of the Aristotelian worldview, and Nicolaus Reimers Baer, known as Ursus, an astronomer at the Imperial court in Prague, whom Tycho Brahe accused of having plagiarized his cosmological model.

Craig tried to contradict Tycho Brahe by using his own observations of the comet, and by questioning his methodology.

Tycho Brahe published an apologia of his conclusions, in which he provided additional arguments, as well as condemning Craig's ideas in strong language for being incompetent.

Craig, who had studied with Wittich, accused Tycho Brahe of minimizing Wittich's role in developing some of the trigonometric methods used by Tycho Brahe.

Tycho Brahe realized that the young king was more interested in war than in science, and was of no mind to keep his father's promise.

Tycho Brahe, who was known to sympathize with the Philippists, followers of Philip Melanchthon, was among the nobles who fell out of grace with the new king.

The king's unfavorable disposition towards Tycho Brahe was likely a result of efforts by several of his enemies at court to turn the king against him.

Tycho Brahe became even more inclined to leave when a mob of commoners, possibly incited by his enemies at court, rioted in front of his house in Copenhagen.

Tycho Brahe left Hven in 1597, bringing some of his instruments with him to Copenhagen, and entrusting others to a caretaker on the island.

Tycho Brahe wrote his most famous poem, Elegy to Dania in which he chided Denmark for not appreciating his genius.

Tycho Brahe received financial support from several nobles in addition to the emperor, including Oldrich Desiderius Pruskowsky von Pruskow, to whom he dedicated his famous.

In return for their support, Tycho Brahe's duties included preparing astrological charts and predictions for his patrons at events such as births, weather forecasting, and astrological interpretations of significant astronomical events, such as the supernova of 1572, sometimes called Tycho Brahe's supernova, and the Great Comet of 1577.

Kepler had previously spoken highly of Ursus, but now found himself in the problematic position of being employed by Tycho Brahe and having to defend his employer against Ursus' accusations, even though he disagreed with both of their planetary models.

Tycho Brahe suddenly contracted a bladder or kidney ailment after attending a banquet in Prague.

The team's conclusion was that "it is impossible that Tycho Brahe could have been murdered".

Tycho Brahe is buried in the Church of Our Lady before Tyn, in Old Town Square near the Prague Astronomical Clock.

Tycho Brahe was the last major astronomer to work without the aid of a telescope, soon to be turned skyward by Galileo Galilei and others.

Tycho Brahe designed larger versions of these instruments, which allowed him to achieve much higher accuracy.

Tycho Brahe aspired to a level of accuracy in his estimated positions of celestial bodies of being consistently within an arcminute of their real celestial locations, and claimed to have achieved this level.

Incorrect transcription in the final published star catalogue, by scribes in Tycho Brahe's employ, was the source of even larger errors, sometimes by many degrees.

Tycho Brahe pioneered an early example while he was a student in Leipzig.

Tycho Brahe made sketches of what he saw as well from comets to the motions of planets.

Tycho Brahe created a quadrant that was thirty-nine centimeters in diameter and added a new type of sight to it called a pinnacidia, or light cutters as it is translated.

Tycho Brahe was critical of the observational data that Copernicus built his theory on, which he correctly considered to be inaccurate.

Tycho Brahe's system had many of the observational and computational advantages of Copernicus' system.

Tycho Brahe's system offered a major innovation in that it eliminated the idea of transparent rotating crystalline spheres to carry the planets in their orbits.

Kepler and other Copernican astronomers, tried unsuccessfully to persuade Tycho Brahe to adopt the heliocentric model of the Solar System.

Tycho Brahe held that the Earth was too sluggish and massive to be continuously in motion.

Tycho Brahe said the Earth was an inert body, not readily moved.

Tycho Brahe acknowledged that the rising and setting of the Sun and stars could be explained by a rotating Earth, as Copernicus had said, still:.

Tycho Brahe believed that, if the Earth did orbit the Sun, there should be an observable stellar parallax every six months.

Tycho Brahe noted and attempted to measure the apparent relative sizes of the stars in the sky.

Tycho Brahe used geometry to show that the distance to the stars in the Copernican system would have to be 700 times greater than the distance from the Sun to Saturn and to be seen at these distances the stars would have to be gigantic, at least as big as the orbit of the Earth, and of course vastly larger than the Sun.

Tycho Brahe believed this because he came to believe Mars had a greater daily parallax than the Sun.

Tycho Brahe said he had therefore rejected Copernicus's model because it predicted Mars would be at only two-thirds the distance of the Sun.

Tycho Brahe discovered librations in the inclination of the plane of the lunar orbit, relative to the ecliptic, and accompanying oscillations in the longitude of the lunar node.

Tycho Brahe was influenced by the Swiss physician Paracelsus, who considered the human body to be directly affected by celestial bodies.

Tycho Brahe used Paracelsus's ideas to connect empiricism and natural science, and religion and astrology.

The expression Tycho Brahe days referred to "unlucky days" that were featured in almanacs from the 1700s onwards, but which have no direct connection to Tycho or his work.

Whether because Tycho Brahe realized that astrology was not an empirical science, or because he feared religious repercussions, he did not publicise his own astrological work.

The first biography of Tycho Brahe, which was the first full-length biography of any scientist, was written by Gassendi in 1654.

In 1913, Dreyer published Tycho Brahe's collected works, facilitating further research.

Early modern scholarship on Tycho Brahe tended to see the shortcomings of his astronomical model, painting him as a mysticist recalcitrant in accepting the Copernican revolution, and valuing mostly his observations that allowed Kepler to formulate his laws of planetary movement.

The traditional view of Tycho Brahe is that he was primarily an empiricist who set new standards for precise and objective measurements.

The Tycho Brahe Prize, inaugurated in 2008, is awarded annually by the European Astronomical Society in recognition of the pioneering development or exploitation of European astronomical instrumentation, or major discoveries based largely on such instruments.

Alfred Noyes in his Watchers of the Sky included a long biographical poem in honour of Tycho Brahe, elaborating on the known history in a highly romantic and imaginative way.

In 2015, the planet Tycho Brahe was named after him as part of the NameExoWorlds campaign.

Tycho Brahe has their own space station named "Tycho Station".