1.

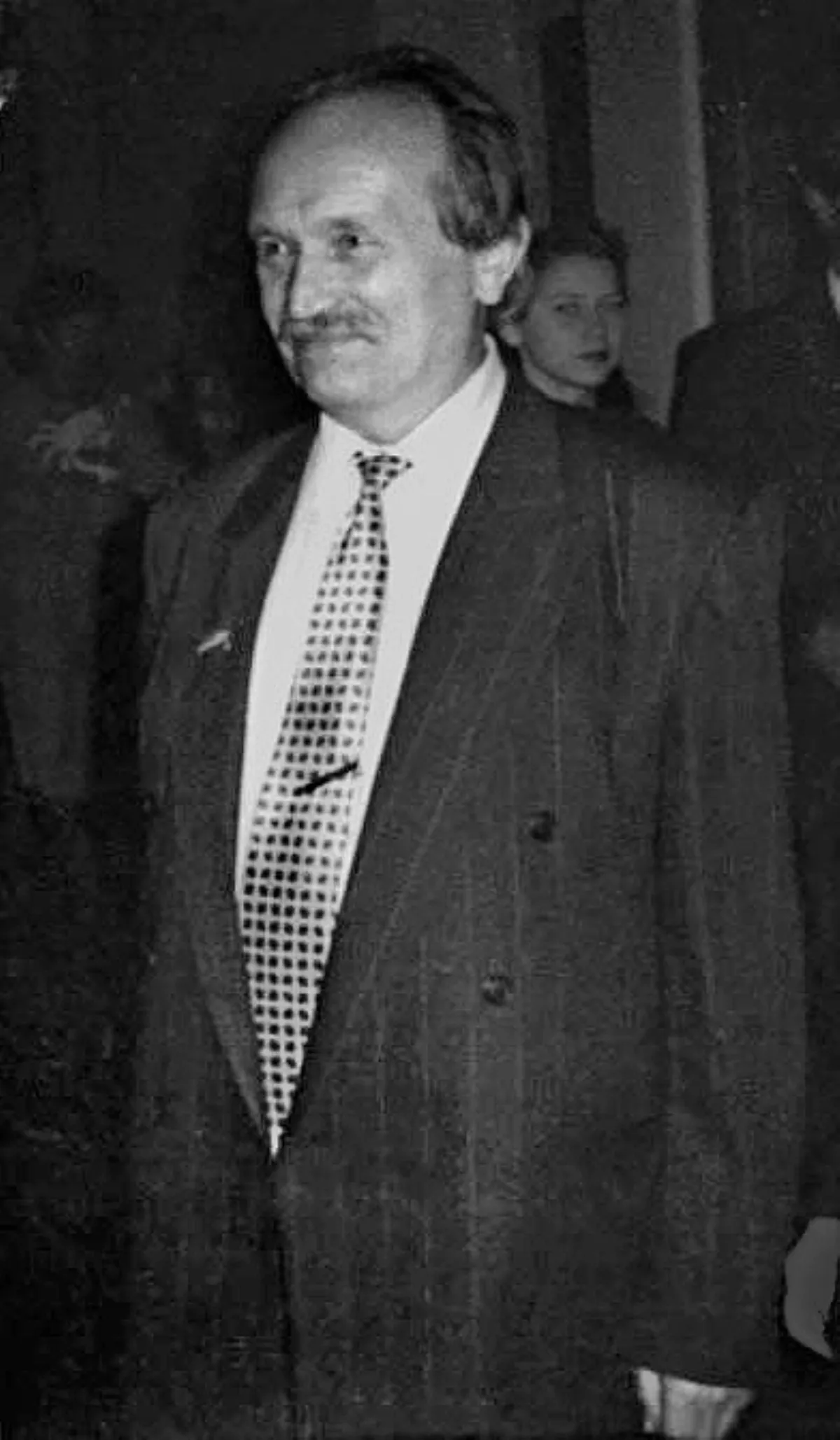

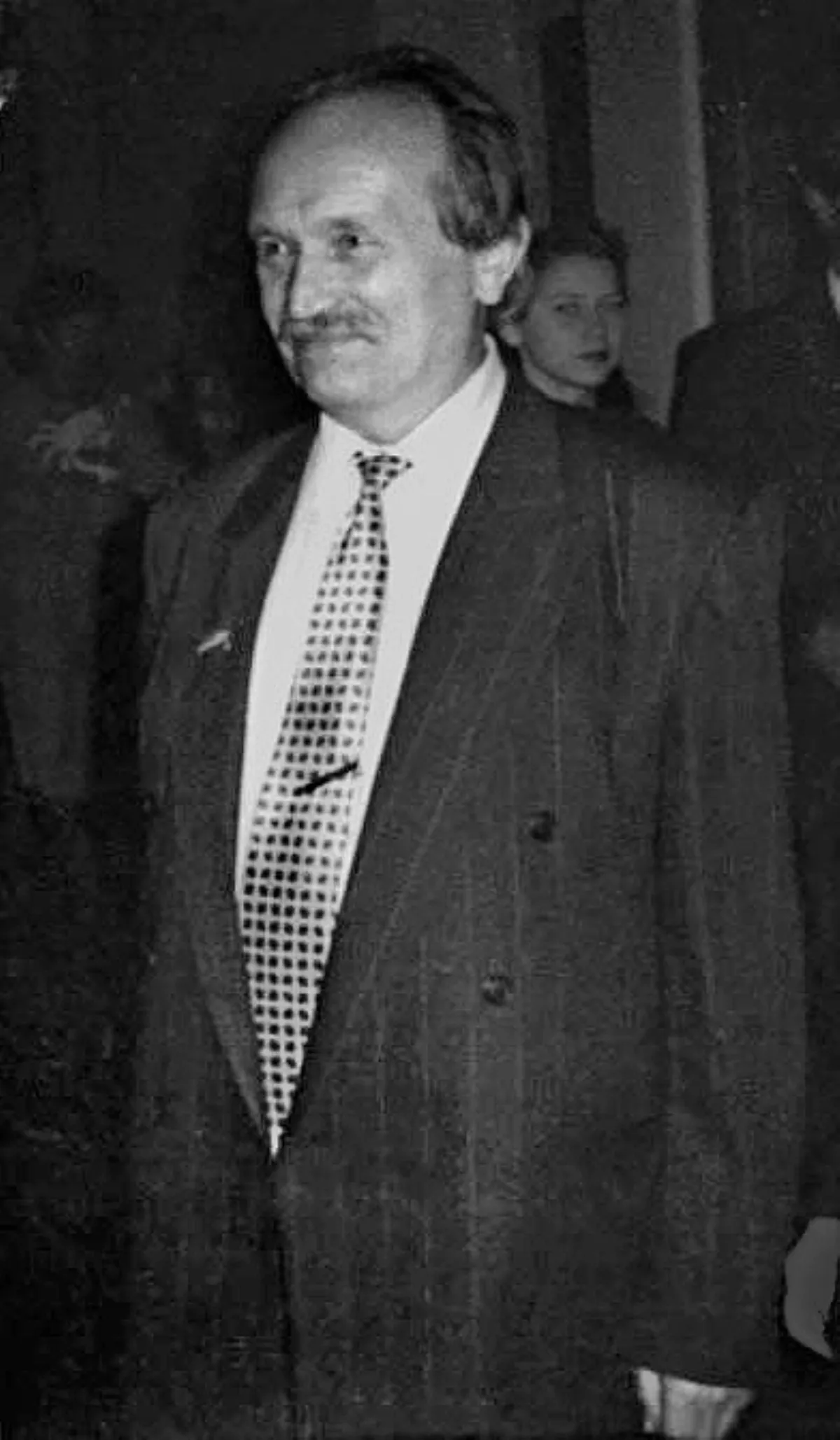

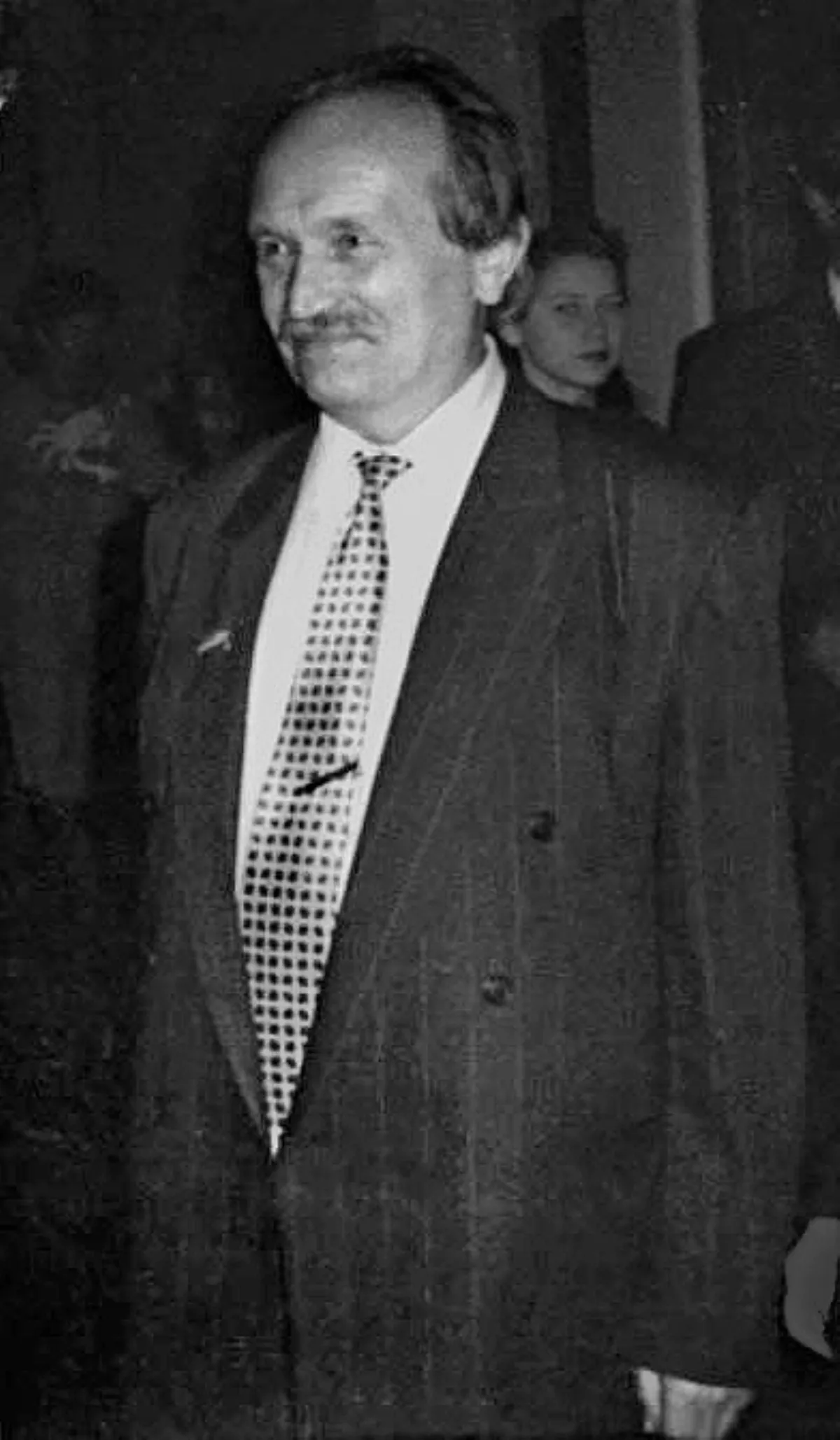

1. Viacheslav Maksymovych Chornovil was a Ukrainian Soviet dissident, independence activist and politician who was the leader of the People's Movement of Ukraine from 1989 until his death in 1999.

1.

1. Viacheslav Maksymovych Chornovil was a Ukrainian Soviet dissident, independence activist and politician who was the leader of the People's Movement of Ukraine from 1989 until his death in 1999.

Viacheslav Chornovil spent fifteen years imprisoned by the Soviet government for his human rights activism, and was later a People's Deputy of Ukraine from 1990 to 1999, being among the first and most prominent anti-communists to hold public office in Ukraine.

Viacheslav Chornovil twice ran for the presidency of Ukraine; the first time, in 1991, he was defeated by Leonid Kravchuk, while in 1999 he died in a car crash under disputed circumstances.

Viacheslav Chornovil was again arrested in another purge of intellectuals in January 1972 and sentenced to between six and twelve years in prison.

Viacheslav Chornovil was described by fellow dissident Mikhail Kheifets as "general of the zeks" for his leadership of Ukrainian political prisoners, and recognised as a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.

Viacheslav Chornovil was allowed to return to Ukraine in 1985 as part of perestroika.

The movement later resulted in a popular revolution that toppled communism and led to Viacheslav Chornovil taking office as a member of Ukraine's parliament.

Viacheslav Chornovil was one of the two main candidates in the 1991 Ukrainian presidential election, though he was defeated by former communist leader Leonid Kravchuk, and he actively promoted Ukrainian membership in the European Union and opposition to the emergence of the Ukrainian oligarchs.

Viacheslav Chornovil frequently made enemies and rivals among Ukraine's far-right and centrist political spheres, and the last months of his life were dominated by a split in his party, the People's Movement of Ukraine.

Viacheslav Chornovil's death in a car crash during the 1999 Ukrainian presidential election, during which he was a candidate in opposition to incumbent president Leonid Kuchma, has led to conspiracy theories and several years of investigations and trials, which have neither confirmed nor eliminated assassination as a possibility.

Viacheslav Chornovil is a popular figure in present-day Ukraine, where he has twice been placed among the top ten most popular Ukrainians and is a symbol of the country's democracy and human rights activism as well as Pro-Europeanism.

Viacheslav Maksymovych Chornovil was born on 24 December 1937 in the village of Yerky, in what was then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, to a family of teachers.

In spite of the Soviet policy of state atheism and the Russification of Ukraine, the young Viacheslav Chornovil was raised in Ukrainian Christian traditions, with his family celebrating Ukrainian festivals in their home.

Viacheslav Chornovil later claimed in his autobiography that following the recapture of Husakove by the Soviet Union, his family was expelled from the village.

Viacheslav Chornovil enrolled at the Taras Shevchenko University of Kyiv the same year, studying to become a journalist.

Viacheslav Chornovil worked as an itinerant editor for the Kyiv Komsomolets newspaper.

Viacheslav Chornovil wrote scripts for the channel's broadcasts, primarily concerning the history of Ukrainian literature.

Viacheslav Chornovil left his job at Lviv Television in May 1963 to return to Kyiv.

Viacheslav Chornovil simultaneously worked as an editor for the Kyiv-based newspapers Young Guard and Second Reading, and was part of the Artistic Youths' Club, an informal group of intellectuals affiliated with the counter-cultural Sixtier movement.

In June 1963, Viacheslav Chornovil married his second wife, Olena Antoniv, and by 1964, Viacheslav Chornovil's second son, Taras, was born.

Viacheslav Chornovil passed exams for post-graduate courses at the Kyiv Paedagogical Institute in 1964, but he was denied the right to take courses on the basis of his political beliefs.

Historian Yaroslav Seko notes that Viacheslav Chornovil's speech placed him as a member of the Sixtiers.

On 8 August 1965, during the opening of a monument to Shevchenko in the village of Sheshory, Viacheslav Chornovil gave a speech with strongly anti-communist overtones.

Later that year, with the purges continuing, Viacheslav Chornovil was called upon to give evidence at the trials of Mykhaylo Osadchy, Bohdan and Mykhailo Horyn, and Myroslava Zvarychevska.

Viacheslav Chornovil refused, and as a result was fired from his editor position at Second Reading.

Viacheslav Chornovil sent the work to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, the Committee for State Security of Ukraine, the Writers' Union of Ukraine, and the Union of Artists of Ukraine.

Viacheslav Chornovil chose to forgo a lawyer, as the latter option at the time carried the risks of having one's arguments distorted and manipulated during interrogations.

Viacheslav Chornovil argued his innocence, as well as that of those who had been arrested during the purge, saying,.

Viacheslav Chornovil stated that the process, and the lack of Soviet authorities' action on his complaints, had significantly reduced his faith in the Soviet system.

Viacheslav Chornovil continued to insist that he had no ill-will towards the Soviet government, alleging that he was being targeted by certain officials who wished to illegally prevent him from informing high-ranking officials about the state of the country.

Viacheslav Chornovil was convicted on 13 November 1967 and sentenced to three years' imprisonment.

In 1969 Viacheslav Chornovil married fellow activist Atena Pashko, whom he had met at the home of Ivan Svitlychnyi.

Pashko later recalled that, on the way back to Chappanda, Viacheslav Chornovil made an impromptu bouquet of St John's wort, while Pashko herself made one from wild roses.

Viacheslav Chornovil was released as part of a general amnesty in 1969.

Viacheslav Chornovil organised further donation campaigns for other formerly-imprisoned dissidents, such as Sviatoslav Karavanskyi and Nina Strokata.

In January 1970 Viacheslav Chornovil launched a new samvydav newspaper, known as The Ukrainian Herald.

The newspaper contained other samvydav publications, as well as information on human rights abuses by the Soviet government and police which Viacheslav Chornovil believed to be contrary to the constitution of the Soviet Union, Great Russian chauvinism and anti-Ukrainian sentiment, and other information regarding the dissident movement in Ukraine.

Viacheslav Chornovil was the chief editor of The Ukrainian Herald, and one of its three editors.

Viacheslav Chornovil established the Civic Committee for the Defence of Nina Strokata on 21 December 1971, following the eponymous activist's arrest.

Viacheslav Chornovil was imprisoned at the KGB pre-trial detention centre in Lviv, alongside Iryna Kalynets, Ivan Gel, Stefaniia Shabatura, Mykhaylo Osadchy and Yaroslav Dashkevych.

Viacheslav Chornovil likewise refused to give evidence against fellow dissidents or cooperate with investigators, stating during a 2 February 1972 interrogation that he believed his trial to be illegal and unrelated to that of other dissidents.

Viacheslav Chornovil was interrogated more than one hundred times during his trial, with 83 interrogations in 1972.

Viacheslav Chornovil was placed in a chamber-type room after refusing to obey any of the rules which prisoners were meant to follow.

Viacheslav Chornovil's activities continued to draw international attention during his imprisonment.

Viacheslav Chornovil was recognised as a prisoner of conscience by human rights group Amnesty International, and awarded the Nicholas Tomalin Prize for Journalism, recognising writers whose freedom of expression is threatened, in 1975.

Around this time Viacheslav Chornovil began to smuggle his writings out of prison, and used the opportunity as a means to continue to demonstrate Soviet human rights abuses.

Viacheslav Chornovil wrote a letter to US President Gerald Ford urging him to match the policy of detente with increased attention towards human rights in the Soviet Union, alleging that the Soviet authorities had used detente as a means by which to suppress dissident voices.

Viacheslav Chornovil was imprisoned at the time of the group's founding, and would not be able to become a member until he was released from prison in 1979.

Viacheslav Chornovil, who was imprisoned in a different camp from Moroz and Shumuk, refused to take a side in the conflict and served as an intermediator.

In early 1977, during a meeting with Shumuk at a hospital, Viacheslav Chornovil accused the former of artificially intensifying his conflict with Moroz, and compared letters by Shumuk to Canadian family members as being equivalent to police complaints.

Viacheslav Chornovil was released from prison and again sent to Chappanda in early 1978.

Viacheslav Chornovil continued to get involved in the conflict between Moroz and Shumuk; in a letter to Moroz's wife Raisa, he called for a public "boycott" of Shumuk, while arguing that Moroz was being inflexible.

Moroz's nine-year imprisonment had seriously impacted his mental and emotional state; Viacheslav Chornovil characterised him as self-aggrandising and narcissistic.

Viacheslav Chornovil wrote a samvydav pamphlet, entitled "Only One Year", and was admitted to PEN International that year.

Viacheslav Chornovil joined the Ukrainian Helsinki Group from exile on 22 May 1979.

Viacheslav Chornovil made contact with several other individuals who wished to establish chapters of the UHG in the oblasts of Ukraine.

Myroslav Marynovych, a member of the UHG, later accused the KGB of outright falsifying information which led to Viacheslav Chornovil's arrest, quoting a KGB officer as stating that "we will not make any more martyrs" by arresting individuals exclusively on political charges.

Viacheslav Chornovil was moved to a prison camp in Tabaga, Yakutia, where he was placed into a cell smeared with vomit and feces.

Viacheslav Chornovil was later held in solitary confinement from 5 to 21 November 1980 as a response to the hunger strike.

Viacheslav Chornovil was found guilty by a closed court in the city of Mirny and sentenced to five years imprisonment.

Viacheslav Chornovil continued to write in prison, including a February 1981 open letter to the 26th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in which he accused General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and KGB chairman Yuri Andropov of orchestrating massive purges against the UHG.

Viacheslav Chornovil wrote to his wife, urging "no compromises" in dissidents' reactions to the congress.

Viacheslav Chornovil wrote another letter on 9 April 1981, this time to the United Nations Human Rights Committee, Amnesty International, the Committee for the Free World, and the Helsinki Committees for Human Rights urging increased attention towards Soviet persecution of the UHG in formulating their diplomatic policies towards the Soviet Union.

Viacheslav Chornovil was released in 1983, but was barred from returning to Ukraine.

Viacheslav Chornovil remained in the town of Pokrovsk, working as a fire stoker.

Viacheslav Chornovil spent a total of 15 years imprisoned by the Soviet government.

Viacheslav Chornovil formally re-launched The Ukrainian Herald on 21 August 1987.

Human rights activities continued to be a significant focus for Viacheslav Chornovil's efforts following his release.

Viacheslav Chornovil was one of the founding members of the Ukrainian Initiative Group for the Liberation of Prisoners of Conscience, led by Mykhailo Horyn.

In one instance, Viacheslav Chornovil was blocked from attending a planned December 1987 seminar on the rights of non-Russian nations within the Soviet Union by being called to a "preventive" interview in Lviv, where he was warned against involvement in "anti-social" activities.

On 11 March 1988 Viacheslav Chornovil formally re-established the Ukrainian Helsinki Group in a letter co-signed by Mykhailo Horyn and Krasivskyi, although the group had already resumed activity in the summer of the previous year.

The fragmented nature of the dissident movement led Viacheslav Chornovil to begin the process of bringing the organisations together into one unified structure in April 1988.

Viacheslav Chornovil created the Ukrainian Helsinki Union on 7 June 1988.

Viacheslav Chornovil additionally supported the spread of Memorial, a human rights movement in the Soviet Union, to Ukraine, writing a positive letter to the presidium of the group's Ukrainian chapter upon its founding in March 1989.

Viacheslav Chornovil supported the strikes from their early days, issuing a statement on 21 July 1989 in part saying,.

Viacheslav Chornovil again mobilised the government against the perceived threat, disparaging the miners in state media and preventing communications between strike committees in various cities.

Viacheslav Chornovil published a pre-election programme for himself in August 1989, ahead of the March 1990 Supreme Soviet election, in which he called for "statehood, democracy, and self-government", cooperation with non-ethnic Ukrainians, and federalism.

Viacheslav Chornovil played a significant role in the event being realised, having pushed for the Unification Act's anniversary to be recognised as a holiday.

Viacheslav Chornovil was elected Chairman of the Lviv Oblast Council in April 1990, making him the first non-communist head of government of Lviv Oblast.

Viacheslav Chornovil quickly adapted from life as a dissident to politics, moving to the right and becoming one of the first Ukrainian politicians to explicitly endorse an anti-communist revolution.

Viacheslav Chornovil's policies were directly at odds with the laws of the Ukrainian SSR and the Soviet Union at the time, and his government was castigated in Ukrainian and Union-wide pro-government media.

Viacheslav Chornovil was appointed as head of the Galician Assembly upon its formation.

Viacheslav Chornovil was nominated as the Democratic Bloc's candidate for Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, though he refused the nomination and endorsed the coalition's leader, Ihor Yukhnovskyi.

Viacheslav Chornovil continued to agitate for federalism, saying in a May 1990 press conference that "Kyivan centralism" would lead to the emergence of Russian nationalism in the Donbas and a Rusyn identity in Zakarpattia Oblast.

Viacheslav Chornovil subsequently revealed that several deputies had received instructions to amend the draft law on sovereignty in order to strip it of measures such as the establishment of an independent military or legal system.

Viacheslav Chornovil continued to advocate for integration of the Galician oblasts, particularly in expanding access to education and inter-oblast trade, at the second meeting of the Galician Assembly on 16 February 1991.

At the time of the coup, Viacheslav Chornovil was in the city of Zaporizhzhia on a business trip.

Viacheslav Chornovil travelled throughout Ukraine to spread the message of Ukrainian independence, including staunchly pro-Russian regions such as Crimea.

Appealling to both Russophone and Ukrainian-language audiences by speaking in both languages, Viacheslav Chornovil argued for a programme in which he would transition from a planned economy to free-market capitalism within a year via a series of decrees and acquiring the attention of Western investors, as well as membership in the European Economic Community and a hypothetical pan-European collective security organisation.

Viacheslav Chornovil condemned Kravchuk as "a sly politician" who was "trying to get [Ukraine] back into the union," warning that he would re-establish political and economic ties with Russia.

Viacheslav Chornovil was initially unpopular due to decades of Soviet propaganda against his beliefs, which Kravchuk had previously directed.

Drach, Horyn and Viacheslav Chornovil were elected as co-chairs of Rukh as a compromise between the two factions.

Viacheslav Chornovil, who had maintained an interest in Crimean Tatars since his imprisonment, called for the Verkhovna Rada to cancel Crimea's declaration of independence and demand new elections to the Verkhovna Rada of Crimea.

Privately, Viacheslav Chornovil expressed a desire to deploy the Ukrainian military to Crimea, but he did not publicly state this as he felt that such a demand would go unfulfilled by Kravchuk or the rest of the government.

Viacheslav Chornovil was among the politicians who supported an independent nuclear arsenal, or alternatively membership in the NATO military alliance, which he felt was the only possible deterrent to Russian expansionism in the case that they were required to relenquish their weapons.

Viacheslav Chornovil initially chose to contest a Kyiv seat in the parliamentary election, as he felt this would establish him as a national figure and give him the opportunity to tour all of Ukraine to spread his ideological vision.

Viacheslav Chornovil has not been seen since, and he is believed to be dead.

At the time of Boichyshyn's abduction, Viacheslav Chornovil was campaigning in the southern Mykolaiv Oblast, and the two had spoken by phone shortly before Boichyshyn was "disappeared".

The New York Times noted after the election that Viacheslav Chornovil was regarded as an expected competitor to Kravchuk, alongside former Prime Minister Leonid Kuchma and Ivan Plyushch, who both won by significant margins after being established as potential opponents of Kravchuk.

Rukh gave a reluctant endorsement of Kravchuk's call to postpone the elections under the justification that not doing so without reform of electoral laws would lead to a political crisis, though Viacheslav Chornovil refused to back an expansion of his powers and argued that he would use it to empower former communist officials and agree to hand over both nuclear weapons and the Black Sea Fleet to Russia.

Viacheslav Chornovil argued that to expand presidential powers would lead to the emergence of "a quiet dictatorship of the oligarchy".

In spite of his electoral success in the parliamentary election, Viacheslav Chornovil decided not to run in the 1994 presidential election and instead endorsed economist Volodymyr Lanovyi, who had been removed from the government by Kravchuk after proposing reforms to end the economic crisis.

Journalist Taras Zdorovylo has claimed that it is possible this decision was taken out of fear for his life and the future of Rukh; according to Zdorovylo, Viacheslav Chornovil used his connections from his time in prison to secretly meet with leading Ukrainian mafia figures, who denied responsibility and claimed that the government had ordered Boichyshyn's abduction.

Kuchma's subsequent crackdown on independent media caused Viacheslav Chornovil to become one of the foremost critics of his government.

Viacheslav Chornovil indicated on 25 March 1995 that he backed Kuchma's proposed constitution, though he expressed that Rukh had "eleven serious objections" to its adoption.

Viacheslav Chornovil was appointed as among the first Ukrainian delegates to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe the same year, and along with the Ukrainian Red Cross Society organised the donation of 50 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Chechen civilians during the First Chechen War.

Viacheslav Chornovil praised Kuchma on a number of occasions during the early years of his presidency for his appointment of National-Democrats to governmental positions.

In 1997, Viacheslav Chornovil escalated his feud with Moroz, condemning his speeches as "primitive populism" and blaming him for the escalation of political polarisation in Ukraine.

Viacheslav Chornovil again led Rukh in the 1998 Ukrainian parliamentary election, this time running as the first candidate on the party's proportional representation list.

Viacheslav Chornovil was joined by Volodymyr Cherniak, Foreign Minister Hennadiy Udovenko, Drach and Environment Minister Yuriy Kostenko as the leading party-list candidates, along with Crimean Tatar activist Mustafa Dzhemilev.

Viacheslav Chornovil called on all National-Democratic parties to form a coalition against the left and the right-wing Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists, additionally arguing for a grand coalition with the pro-Kuchma People's Democratic Party and the Social Democratic Party of Ukraine.

Ukrainian historian Pavlo Hai-Nyzhnyk has said that Viacheslav Chornovil withdrew his name from the presidential nomination in January 1999 and according to the Jamestown Foundation he endorsed Udovenko, though Viacheslav Chornovil's son Taras has disputed this, saying he was still campaigning for the presidency until his death.

Viacheslav Chornovil responded at a 22 February press conference where he compared them to the State Committee on the State of Emergency that led the 1991 Soviet coup attempt and accused them of taking $40,000 per month from the Ukrainian government, of taking 4,000 hryvnias from a Rukh office, and of taking a million-dollar bribe from Rukh People's Deputy Oleh Ishchenko.

Mykola Stepanenko, a Ministry of Internal Affairs employee tasked with investigating Viacheslav Chornovil's death, noted Babenko as an individual who had substantial knowledge of Viacheslav Chornovil's daily routine and travel plans.

On 24 March 1999, Viacheslav Chornovil was at a campaign event in the city of Kirovohrad, either for himself or Udovenko.

Viacheslav Chornovil further claimed that Kuchma could only win by assassinating his opponents or turning them against one another.

Shortly before midnight on 25 March 1999, Viacheslav Chornovil was returning to Kyiv from Kirovohrad with aide Yevhen Pavlov and Rukh press secretary Dmytro Ponomarchuk.

Viacheslav Chornovil was granted a state honour guard, as well as a military orchestra.

Suspicions of Ukrainian government involvement in Viacheslav Chornovil's death emerged almost immediately, inflamed by Viacheslav Chornovil's controversial nature and the impending presidential election.

The first attempt to investigate Viacheslav Chornovil's death began with a Verkhovna Rada commission in April 1999.

On 6 September 2006, Minister of Internal Affairs Yuriy Lutsenko declared that Viacheslav Chornovil had been murdered and that evidence proving it had been handed over to the Prosecutor General of Ukraine.

Since then, investigations into Viacheslav Chornovil's death have been repeatedly closed and reopened without concluding whether Viacheslav Chornovil was the victim of an assassination plot or a simple car crash.

Viacheslav Chornovil has twice been placed among the ten most popular Ukrainians of all time.