1.

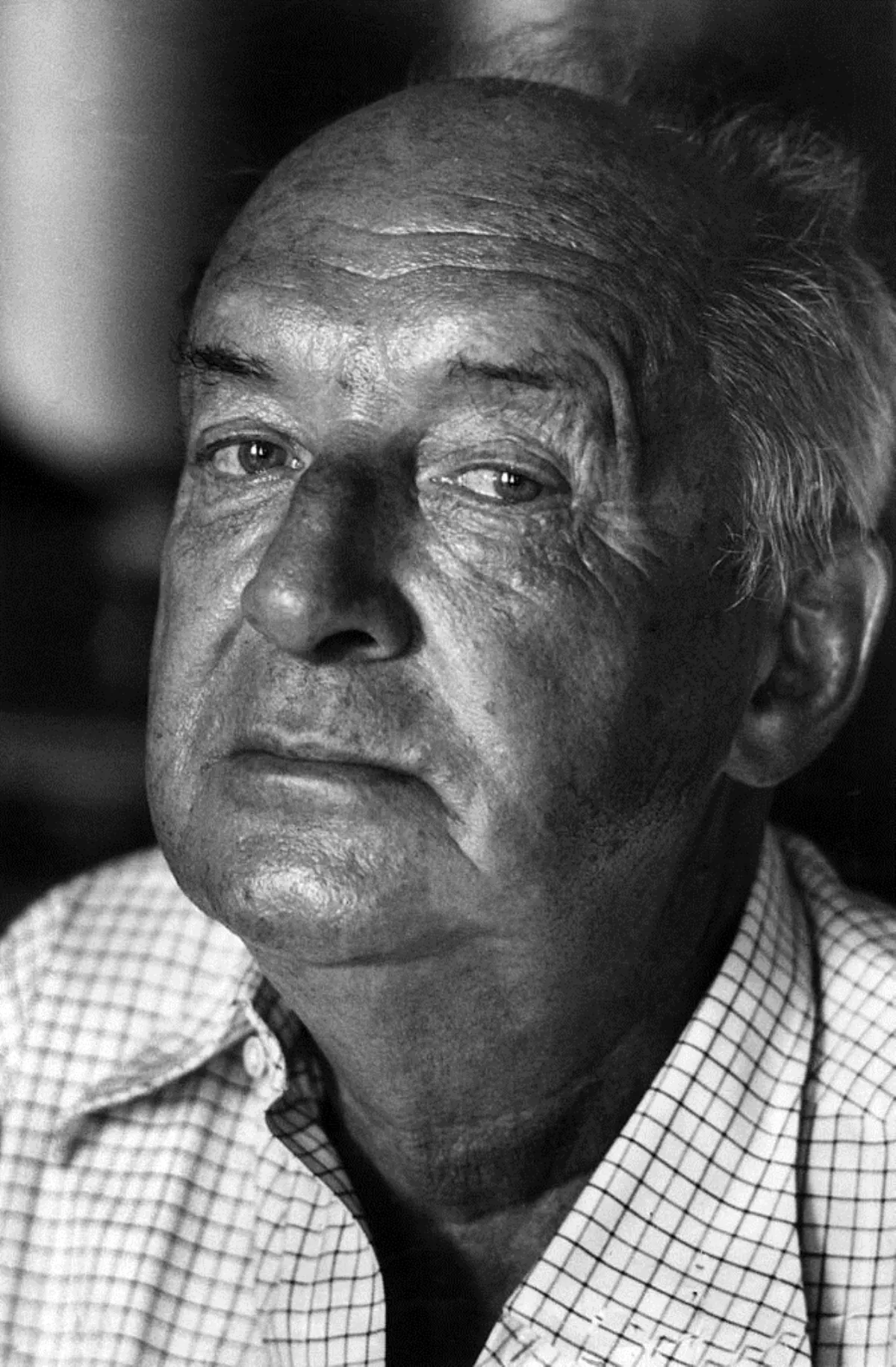

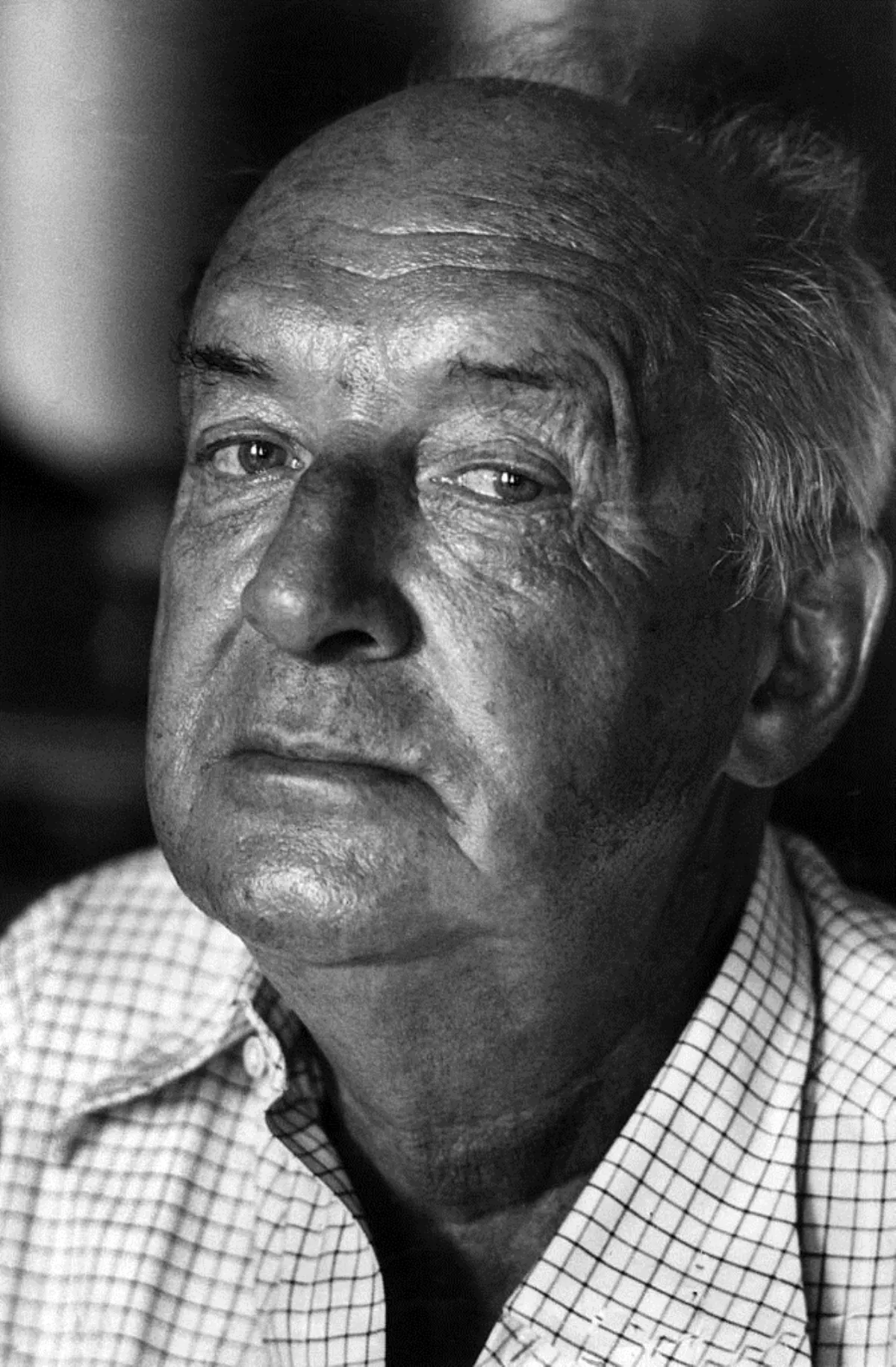

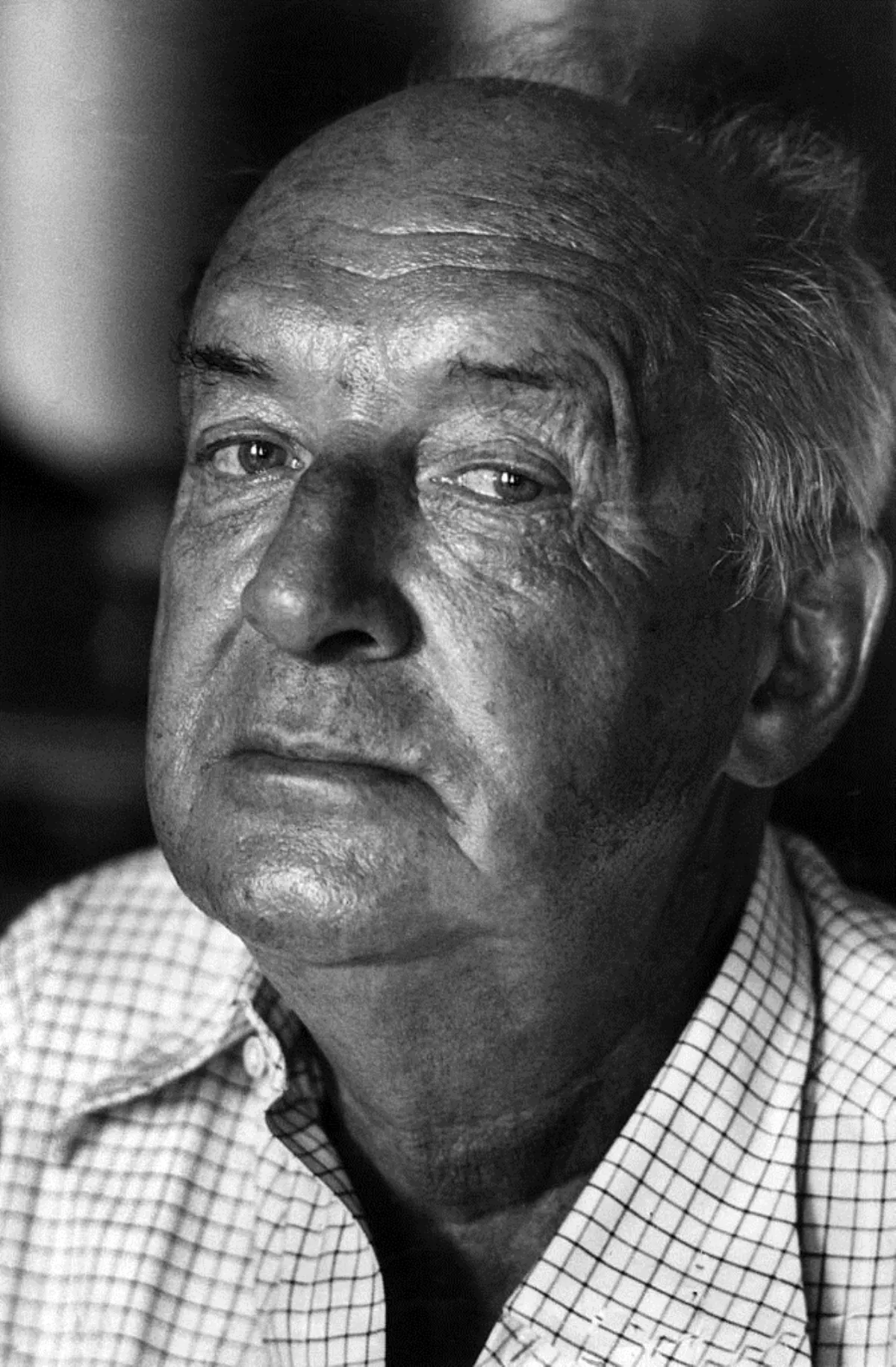

1. Vladimir Nabokov achieved international acclaim and prominence after moving to the United States, where he began writing in English.

1.

1. Vladimir Nabokov achieved international acclaim and prominence after moving to the United States, where he began writing in English.

Trilingual in Russian, English, and French, Vladimir Nabokov became a US citizen in 1945 and lived mostly on the East Coast before returning to Europe in 1961, where he settled in Montreux, Switzerland.

From 1948 to 1959, Vladimir Nabokov was a professor of Russian literature at Cornell University.

Vladimir Nabokov's memoir, Speak, Memory, published in 1951, is considered among the greatest nonfiction works of the 20th century, placing eighth on Random House's ranking of 20th-century works.

Vladimir Nabokov was a seven-time finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction.

Vladimir Nabokov was an expert lepidopterist and composer of chess problems.

Time magazine wrote that Vladimir Nabokov had "evolved a vivid English style which combines Joycean word play with a Proustian evocation of mood and setting".

Vladimir Nabokov was born on 22 April 1899 in Saint Petersburg to a wealthy and prominent family of the Russian nobility.

Vladimir Nabokov's family traced its roots to the 14th-century Tatar prince Nabok Murza, who entered into the service of the Tsars, and from whom the family name is derived.

Vladimir Nabokov's father was Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, a liberal lawyer, statesman, and journalist, and his mother was the heiress Yelena Ivanovna nee Rukavishnikova, the granddaughter of a millionaire gold-mine owner.

Vladimir Nabokov's father was a leader of the pre-Revolutionary liberal Constitutional Democratic Party, and wrote numerous books and articles about criminal law and politics.

Vladimir Nabokov had four younger siblings: Sergey, Olga, Elena, and Kirill.

Vladimir Nabokov spent his childhood and youth in Saint Petersburg and at the country estate Vyra near Siverskaya, south of the city.

The family spoke Russian, English, and French in their household, and Vladimir Nabokov was trilingual from an early age.

Vladimir Nabokov related that the first English book his mother read to him was Misunderstood, by Florence Montgomery.

Much to his patriotic father's disappointment, Vladimir Nabokov could read and write in English before he could in Russian.

Vladimir Nabokov's ability to recall his past in vivid detail was a boon to him during his permanent exile, providing a theme that runs from his first book, Mary, to later works such as Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle.

Vladimir Nabokov was not forced to attend church after he lost interest.

In 1916, Vladimir Nabokov inherited the estate Rozhdestveno, next to Vyra, from his uncle Vasily Ivanovich Rukavishnikov.

Vladimir Nabokov's adolescence was the period in which he made his first serious literary endeavors.

Vladimir Nabokov took the second part of the exam in his fourth year just after his father's death, and feared he might fail it.

Vladimir Nabokov later drew on his Cambridge experiences to write several works, including the novels Glory and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight.

In 1920, Vladimir Nabokov's family moved to Berlin, where his father set up the emigre newspaper Rul'.

Vladimir Nabokov followed them to Berlin two years later, after completing his studies at Cambridge.

Vladimir Nabokov drew upon his father's death repeatedly in his fiction.

Vladimir Nabokov lived within the lively Russian community of Berlin that was more or less self-sufficient, staying on after it had disintegrated because he had nowhere else to go to.

Vladimir Nabokov knew few Germans except for landladies, shopkeepers, and immigration officials at the police headquarters.

In 1922, Vladimir Nabokov became engaged to Svetlana Siewert, but she broke the engagement off early in 1923 when her parents worried whether he could provide for her.

In 1937, Vladimir Nabokov left Germany for France, where he had a short affair with Irina Guadanini, a Russian emigree.

Vladimir Nabokov's family followed him to France, making en route their last visit to Prague, then spent time in Cannes, Menton, Cap d'Antibes, and Frejus, finally settling in Paris.

In 1939, in Paris, Vladimir Nabokov wrote the 55-page novella The Enchanter, his final work of Russian fiction.

The Nabokovs settled in Manhattan, and Vladimir began volunteer work as an entomologist at the American Museum of Natural History.

Vladimir Nabokov joined the staff of Wellesley College in 1941 as resident lecturer in comparative literature.

Vladimir Nabokov is remembered as the founder of Wellesley's Russian department.

Vladimir Nabokov's classes were popular, due as much to his unique teaching style as to the wartime interest in all things Russian.

Vladimir Nabokov wrote Lolita while traveling on the butterfly-collection trips in the western US that he undertook every summer.

Vera acted as "secretary, typist, editor, proofreader, translator and bibliographer; his agent, business manager, legal counsel and chauffeur; his research assistant, teaching assistant and professorial understudy"; when Vladimir Nabokov attempted to burn unfinished drafts of Lolita, Vera stopped him.

Vladimir Nabokov called her the best-humored woman he had ever known.

Vladimir Nabokov roamed the nearby mountains looking for butterflies, and wrote a poem called "Lines Written in Oregon".

Vladimir Nabokov died of bronchitis on 2 July 1977 in Montreux.

Vladimir Nabokov's remains were cremated and buried at Clarens cemetery in Montreux.

Vladimir Nabokov is known as one of the leading prose stylists of the 20th century; his first writings were in Russian, but he achieved his greatest fame with the novels he wrote in English.

Vladimir Nabokov's trilingual upbringing had a profound influence on his art.

Vladimir Nabokov himself translated into Russian two books he originally wrote in English, Conclusive Evidence and Lolita.

The "translation" of Conclusive Evidence was made because Vladimir Nabokov felt that the English version was imperfect.

Vladimir Nabokov was a proponent of individualism, and rejected concepts and ideologies that curtailed individual freedom and expression, such as totalitarianism in its various forms, as well as Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis.

Vladimir Nabokov makes cameo appearances in some of his novels, such as the character Vivian Darkbloom, who appears in both Lolita and Ada, or Ardor, and the character Blavdak Vinomori in King, Queen, Knave.

Vladimir Nabokov is noted for his complex plots, clever word play, daring metaphors, and prose style capable of both parody and intense lyricism.

Vladimir Nabokov gained both fame and notoriety with Lolita, which recounts a grown man's consuming passion for a 12-year-old girl.

Vladimir Nabokov devoted more time to the composition of it than to any other.

Vladimir Nabokov firmly believed that novels should not aim to teach and that readers should not merely empathize with characters but that a 'higher' aesthetic enjoyment should be attained, partly by paying great attention to details of style and structure.

Vladimir Nabokov detested what he saw as 'general ideas' in novels, and so when teaching Ulysses, for example, he would insist students keep an eye on where the characters were in Dublin rather than teaching the complex Irish history that many critics see as being essential to an understanding of the novel.

Vladimir Nabokov wanted his students to describe the details of the novels rather than a narrative of the story and was very strict when it came to grading.

The novelist John Hawkes took inspiration from Vladimir Nabokov and considered himself his follower.

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Michael Chabon listed Lolita and Pale Fire among the "books that, I thought, changed my life when I read them", and has said, "Vladimir Nabokov's English combines aching lyricism with dispassionate precision in a way that seems to render every human emotion in all its intensity but never with an ounce of schmaltz or soggy language".

Vladimir Nabokov was a classical liberal, in the tradition of his father, a liberal statesman who served in the Provisional Government following the February Revolution of 1917 as a member of the Constitutional Democratic Party.

In Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov proudly recounted his father's campaigns against despotism and staunch opposition to capital punishment.

Vladimir Nabokov was a self-proclaimed "White Russian", and was, from its inception, a strong opponent of the Soviet government that came to power following the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917.

Racism against African-Americans appalled Vladimir Nabokov, who touted Alexander Pushkin's multiracial background as an argument against segregation.

Vladimir Nabokov was a self-described synesthete, who at a young age equated the number five with the color red.

Vladimir Nabokov's wife exhibited synesthesia; like her husband, her mind's eye associated colors with particular letters.

Vladimir Nabokov wrote that his mother had synesthesia, and that she had different letter-color pairs.

Many other subtle references are made in Vladimir Nabokov's writing that can be traced back to his synesthesia.

Vladimir Nabokov described his synesthesia at length in his autobiography Speak, Memory:.

Vladimir Nabokov was very open about, and received criticism for, his indifference to organized mysticism, to religion, and to any church.

Vladimir Nabokov was a notorious, lifelong insomniac who admitted unease at the prospect of sleep, once saying, "the night is always a giant".

Vladimir Nabokov spent considerable time during his exile composing chess problems, which he published in Germany's Russian emigre press, Poems and Problems and Speak, Memory.

Vladimir Nabokov describes the process of composing and constructing in his memoir: "The strain on the mind is formidable; the element of time drops out of one's consciousness".