1.

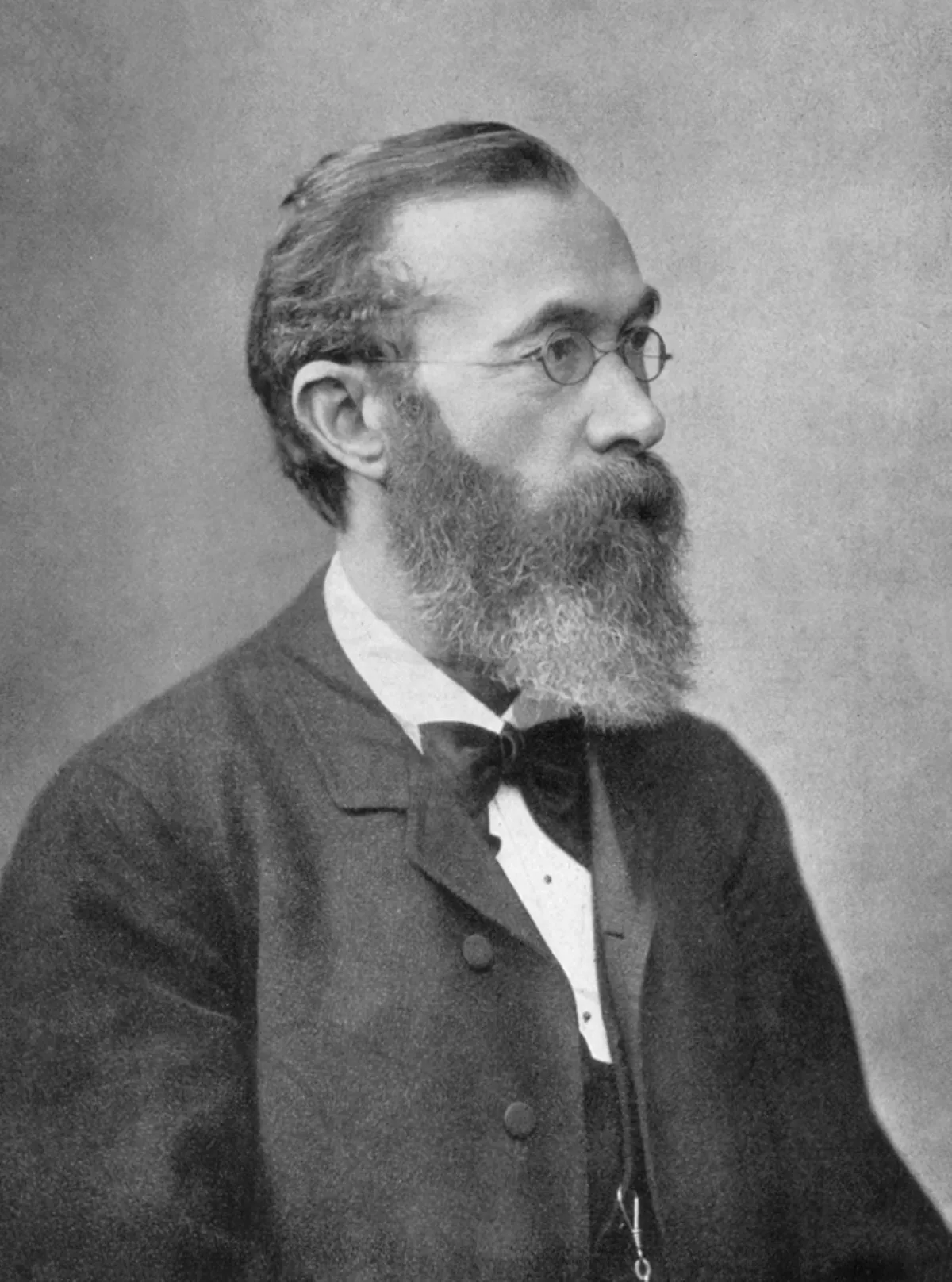

1. Wilhelm Wundt is widely regarded as the "father of experimental psychology".

1.

1. Wilhelm Wundt is widely regarded as the "father of experimental psychology".

In 1879, at the University of Leipzig, Wilhelm Wundt founded the first formal laboratory for psychological research.

Wilhelm Wundt established the first academic journal for psychological research, Philosophische Studien, followed by Psychologische Studien, to publish the institute's research.

Wilhelm Wundt was born at Neckarau, Baden on 16 August 1832, the fourth child to parents Maximilian Wilhelm Wundt, a Lutheran minister, and Marie Frederike, nee Arnold.

Two of Wilhelm Wundt's siblings died in childhood; his brother, Ludwig, survived.

When Wilhelm Wundt was about six years of age, his family moved to Heidelsheim, then a small medieval town in Baden-Wurttemberg.

Wilhelm Wundt studied from 1851 to 1856 at the University of Tubingen, at the University of Heidelberg, and at the University of Berlin.

Wilhelm Wundt applied himself to writing a work that came to be one of the most important in the history of psychology, Principles of Physiological Psychology, in 1874.

The couple had three children: Eleanor, who became an assistant to her father in many ways, Louise, called Lilli, and Max Wilhelm Wundt, who became a philosophy professor.

In 1879, at the University of Leipzig, Wilhelm Wundt opened the first laboratory ever to be exclusively devoted to psychological studies, and this event marked the official birth of psychology as an independent field of study.

Wilhelm Wundt arranged for the construction of suitable instruments and collected many pieces of equipment such as tachistoscopes, chronoscopes, pendulums, electrical devices, timers, and sensory mapping devices, and was known to assign an instrument to various graduate students with the task of developing uses for future research in experimentation.

In 1879, Wilhelm Wundt began conducting experiments that were not part of his course work, and he claimed that these independent experiments solidified his lab's legitimacy as a formal laboratory of psychology, though the university did not officially recognize the building as part of the campus until 1883.

The Psychological Institute, as it became known, eventually moved to a new building that Wilhelm Wundt had designed specifically for psychological research.

Wilhelm Wundt was responsible for an extraordinary number of doctoral dissertations between 1875 and 1919: 185 students including 70 foreigners.

Several of Wilhelm Wundt's students became eminent psychologists in their own right.

Wilhelm Wundt, thus, is present in the academic "family tree" of the majority of American psychologists, first and second generation.

Much of Wilhelm Wundt's work was derided mid-century in the United States because of a lack of adequate translations, misrepresentations by certain students, and behaviorism's polemic with Wilhelm Wundt's program.

Wilhelm Wundt retired in 1917 to devote himself to his scientific writing.

Wilhelm Wundt is buried in Leipzig's South Cemetery with his wife, Sophie, and their daughters, Lilli and Eleanor.

Wilhelm Wundt was awarded honorary doctorates from the Universities of Leipzig and Gottingen, and the Pour le Merite for Science and Arts.

Wilhelm Wundt was nominated three times for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Wilhelm Wundt was an honorary member of 12 scientific organizations or societies.

Wilhelm Wundt was a corresponding member of 13 academies in Germany and abroad.

Wilhelm Wundt was initially a physician and a well-known neurophysiologist before turning to sensory physiology and psychophysics.

Wilhelm Wundt was convinced that, for example, the process of spatial perception could not solely be explained on a physiological level, but involved psychological principles.

Wilhelm Wundt founded experimental psychology as a discipline and became a pioneer of cultural psychology.

Wilhelm Wundt's work remains largely inaccessible without advanced knowledge of German.

Wilhelm Wundt conducted experiments on memory, which would be considered today as iconic memory, short-term memory, and enactment and generation effects.

Wilhelm Wundt considered that reference to the subject, value assessment, the existence of purpose, and volitional acts to be specific and fundamental categories for psychology.

Wilhelm Wundt frequently used the formulation "the human as a motivated and thinking subject" in order to characterise features held in common with the humanities and the categorical difference to the natural sciences.

Wilhelm Wundt follows Leibniz and differentiates between a physical causality and a mental causality of the consciousness process.

Unlike other thinkers of his time, Wilhelm Wundt had no difficulty connecting the development concepts of the humanities with the biological theory of evolution as expounded by Charles Darwin.

Wilhelm Wundt set himself the task of redefining the broad field of psychology between philosophy and physiology, between the humanities and the natural sciences.

Wilhelm Wundt's concepts were developed during almost 60 years of research and teaching that led him from neurophysiology to psychology and philosophy.

The initial conceptual outlines of the 30-year-old Wilhelm Wundt led to a long research program, to the founding of the first Institute and to the treatment of psychology as a discipline, as well as to a range of fundamental textbooks and numerous other publications.

Wilhelm Wundt wrote about 70 reviews of current publications in the fields of neurophysiology and neurology, physiology, anatomy and histology.

Wilhelm Wundt wanted to connect two sciences with one another.

Wilhelm Wundt describes the sensory impression with the simple sensory feelings, perceptions and volitional acts connected with them, and he explains dependencies and feedbacks.

Wilhelm Wundt rejected the widespread association theory, according to which mental connections are mainly formed through the frequency and intensity of particular processes.

Wilhelm Wundt describes apperceptive processes as psychologically highly differentiated and, in many regards, bases this on methods and results from his experimental research.

Wilhelm Wundt critically analysed the, in his view, still disorganised intentions of Lazarus and Steinthal and limited the scope of the issues by proposing a psychologically constituted structure.

Wilhelm Wundt worked on, psychologically linked, and structured an immense amount of material.

Wilhelm Wundt recognized about 20 fundamental dynamic motives in cultural development.

Wilhelm Wundt saw examples of human self-education in walking upright, physical facilities and "an interaction in part forced upon people by external conditions and in part the result of voluntary culture".

Wilhelm Wundt described the random appearance and later conscious control of fire as a similar interaction between two motives.

Wilhelm Wundt considered calling it Anthropology, Social Psychology and Community Psychology.

Wilhelm Wundt contributed to the state of neuropsychology as it existed at the time in three ways: through his criticism of the theory of localisation, through his demand for research hypotheses founded on both neurological and psychological thinking, and through his neuropsychological concept of an apperception centre in the frontal cortex.

Wilhelm Wundt considered attention and the control of attention an excellent example of the desirable combination of experimental psychological and neurophysiological research.

Wilhelm Wundt called for experimentation to localise the higher central nervous functions to be based on clear, psychologically based research hypotheses because the questions could not be rendered precisely enough on the anatomical and physiological levels alone.

Wilhelm Wundt based his central theory of apperception on neuropsychological modelling.

Wilhelm Wundt is therefore a forerunner of current research on cognitive and emotional executive functions in the prefrontal cerebral cortex, and on hypothetical multimodal convergence zones in the network of cortical and limbic functions.

Kant had argued against the assumption of the measurability of conscious processes and made a well-founded, if very short, criticism of the methods of self-observation: regarding method-inherent reactivity, observer error, distorting attitudes of the subject, and the questionable influence of independently thinking people, but Wilhelm Wundt expressed himself optimistic that methodological improvements could be of help here.

Wilhelm Wundt later admitted that measurement and mathematics were only applicable for very elementary conscious processes.

Wilhelm Wundt differentiated between two objectives of comparative methodology: individual comparison collected all the important features of the overall picture of an observation material, while generic comparison formed a picture of variations to obtain a typology.

Wilhelm Wundt mainly differentiated between four principles and explained them with examples that originate from the physiology of perception, the psychology of meaning, from apperception research, emotion and motivation theory, and from cultural psychology and ethics.

Wilhelm Wundt demands co-ordinated analysis of causal and teleological aspects; he called for a methodologically versatile psychology and did not demand that any decision be made between experimental-statistical methods and interpretative methods.

Wilhelm Wundt was very familiar with these methods and used them in extended research projects.

Those who follow up these references will find that Wilhelm Wundt critically analysed both these thinkers' ideas.

Wilhelm Wundt distanced himself from Herbart's science of the soul and, in particular, from his "mechanism of mental representations" and pseudo-mathematical speculations.

Wilhelm Wundt gave up his plans for a biography of Leibniz, but praised Leibniz's thinking on the two-hundredth anniversary of his death in 1916.

Wilhelm Wundt did disagree with Leibniz's monadology as well as theories on the mathematisation of the world by removing the domain of the mind from this view.

Wilhelm Wundt secularised such guiding principles and reformulated important philosophical positions of Leibniz away from belief in God as the creator and belief in an immortal soul.

Wilhelm Wundt's differentiation between the "natural causality" of neurophysiology and the "mental causality" of psychology, is a direct rendering from Leibniz's epistemology.

Wilhelm Wundt devised the term psychophysical parallelism and meant thereby two fundamentally different ways of considering the postulated psychophysical unit, not just two views in the sense of Fechner's theory of identity.

Wilhelm Wundt derived the co-ordinated consideration of natural causality and mental causality from Leibniz's differentiation between causality and teleology.

Wilhelm Wundt had developed the first genuine epistemology and methodology of empirical psychology.

Wilhelm Wundt shaped the term apperception, introduced by Leibniz, into an experimental psychologically based apperception psychology that included neuropsychological modelling.

Unlike the great majority of contemporary and current authors in psychology, Wilhelm Wundt laid out the philosophical and methodological positions of his work clearly.

Wilhelm Wundt was against the founding empirical psychology on a principle of soul as in Christian belief in an immortal soul or in a philosophy that argues "substance"-ontologically.

Wilhelm Wundt's position was decisively rejected by several Christianity-oriented psychologists and philosophers as a psychology without soul, although he did not use this formulation from Friedrich Lange, who was his predecessor in Zurich from 1870 to 1872.

Wilhelm Wundt's guiding principle was the development theory of the mind.

Wilhelm Wundt's ethics led to polemical critiques due to his renunciation of an ultimate transcendental basis of ethics.

Wilhelm Wundt's evolutionism was criticised for its claim that ethical norms had been culturally changed in the course of human intellectual development.

Wilhelm Wundt distanced himself from the metaphysical term soul and from theories about its structure and properties, as posited by Herbart, Lotze, and Fechner.

Wilhelm Wundt is concerned about psychologists bringing their own personal metaphysical convictions into psychology and that these presumptions would no longer be exposed to epistemological criticism.

Wilhelm Wundt extrapolated this empirically founded volitional psychology to a metaphysical voluntarism.

Wilhelm Wundt interpreted intellectual-cultural progress and biological evolution as a general process of development whereby he did not want to follow the abstract ideas of entelechy, vitalism, animism, and by no means Schopenhauer's volitional metaphysics.

Wilhelm Wundt believed that the source of dynamic development was to be found in the most elementary expressions of life, in reflexive and instinctive behaviour, and constructed a continuum of attentive and apperceptive processes, volitional or selective acts, up to social activities and ethical decisions.

Wilhelm Wundt spoke on the idea of humanity in ethics, on human rights and human duties in his speech as Rector of Leipzig University in 1889 on the centenary of the French Revolution.

Wilhelm Wundt divided up his three-volume Logik into General logic and epistemology, Logic of the exact sciences, and Logic of the humanities.

The subsequent equitable description of the special principles of the natural sciences and the humanities enabled Wilhelm Wundt to create a new epistemology.

The American psychologist Edwin Boring counted 494 publications by Wilhelm Wundt that are, on average, 110 pages long and amount to a total of 53,735 pages.

Wilhelm Wundt was a member of the liberal Progressive Party of Baden.

Wilhelm Wundt spent several afternoons every week in his adjacent modest Professorial office, came to see us, advised us and often got involved in the experiments; he was available to us at any time.

Wilhelm Wundt never claimed that psychology could be advanced through experiment and measurement alone, but had already stressed in 1862 that the development history of the mind and comparative psychology should provide some assistance.

Wilhelm Wundt attempted to redefine and restructure the fields of psychology and philosophy.

Massive misconceptions about Wilhelm Wundt's work have been demonstrated by William James, Granville Stanley Hall, Edward Boring and Edward Titchener as well as among many later authors.

Wilhelm Wundt was involved in a number of scientific controversies or was responsible for triggering them:.

Wilhelm Wundt further influenced many American psychologists to create psychology graduate programs.

Wilhelm Wundt developed the first comprehensive and uniform theory of the science of psychology.

Wilhelm Wundt demanded the ability and readiness to distinguish between perspectives and reference systems, and to understand the necessary supplementation of these reference systems in changes of perspective.

Wilhelm Wundt defined the field of psychology very widely and as interdisciplinary, and explained just how indispensable is the epistemological-philosophical criticism of psychological theories and their philosophical prerequisites.

The fundamental reconstruction of Wilhelm Wundt's main ideas is a task that cannot be achieved by any one person today due to the complexity of the complete works.

Caution: Earlier translations of Wilhelm Wundt's publications are of a highly questionable reliability.