1.

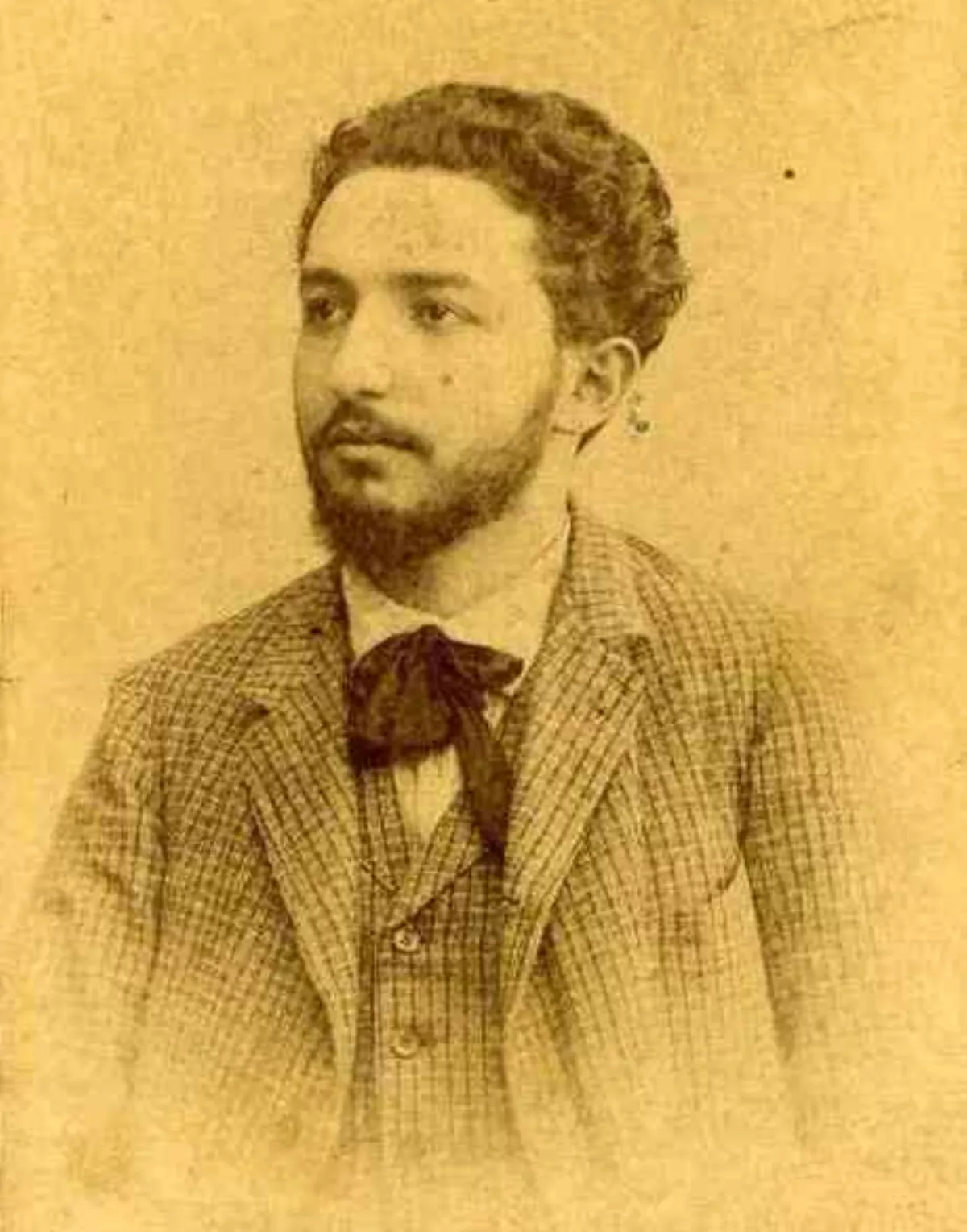

1. Alexander Movsesi Atabekian was an Armenian physician, publisher and anarchist communist.

1.

1. Alexander Movsesi Atabekian was an Armenian physician, publisher and anarchist communist.

In Geneva, Atabekian established the Anarchist Library, which published several seminal anarchist texts in the Armenian and Russian languages, with the intention of smuggling them into the Russian Empire.

Alexander Atabekian made links with the nascent Armenian Revolutionary Federation, helping to set up publication of its newspaper Droshak in Geneva.

Alexander Atabekian pursued his medical studies to Paris, where he began publishing the journal Hamaink, the first anarchist periodical in the Armenian language.

Alexander Atabekian wrote extensively about the oppression of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire and European countries and elaborated his vision for a social revolution in Armenia.

Alexander Atabekian ceased publication after hearing news of the Hamidian massacres, after which he re-established connections with other anarchists within the ARF.

Alexander Atabekian worked as a combat medic during World War I, during which he treated refugees that had fled the Armenian genocide.

Alexander Atabekian was critical of the rise of the Bolsheviks, whom he saw as working in opposition to the will of the people.

Alexander Atabekian instead advocated for the strengthening of the co-operative movement, seeing particular promise in Moscow's house committees as a means to establish socialist anarchism.

Alexander Atabekian acted as Kropotkin's personal doctor and confidant, staying by his side until his death.

Alexander Atabekian then participated in the management of a museum of Kropotkin, which he maintained throughout the period of the New Economic Policy.

Alexander Atabekian has since been held as a key example of an anarchist from outside the Western tradition, and his work on anti-authoritarianism, co-operative economics and tenants rights has been studied in Russia and Ukraine.

Alexander Movsesi Atabekian was born on 2 February 1869, in Shushi, a city in the region of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Alexander Atabekian was born into an Armenian noble family and was the son of a physician.

Alexander Atabekian left the SDHP and became an anarchist communist in 1890, after reading Words of a Rebel, a collection of writings by Peter Kropotkin.

Alexander Atabekian then began working at a Ukrainian publishing house, which he used to print translations of anarchist works in the Armenian and Russian languages.

Alexander Atabekian published a number of open letters, on behalf of the international anarchist movement, to Armenian peasants and revolutionaries.

Alexander Atabekian met Max Nettlau, Paraskev Stoyanov, Luigi Galleani and Jacques Gross; with whom he printed a poster in memory of the Haymarket martyrs, which they plastered throughout Geneva.

Alexander Atabekian then returned to Geneva and established a printing press in his own bedroom; he called it the Anarchist Library, and it would become the first Russian anarchist propaganda circle since Zamfir Arbore's own in the 1870s.

Alexander Atabekian had planned to start by publishing a Russian language edition of Words of a Rebel, but Kropotkin was overwhelmed by work and unable to translate more than a few chapters, leaving the rest to Varlam Cherkezishvili.

Alexander Atabekian initially lacked the resources to publish a periodical, so decided to start out publishing individual pamphlets.

Alexander Atabekian's first publication was a Russian language edition of Mikhail Bakunin's The Paris Commune and the Idea of the State, which was followed in 1892 by Kropotkin's The Destruction of the State.

In 1893, he published Kropotkin's Political Rights, Anarchism and Spirit of Revolt, as well as Reclus' To My Brother the Peasant, and Errico Malatesta's Between Peasants, the latter of which Alexander Atabekian wrote a preface directing it towards Armenians.

Alexander Atabekian moved first to Lyon, where he spent a few months working at a state-of-the-art clinic.

Alexander Atabekian's publishing work slowed down at this time, but didn't stop entirely, as he waited for further sheets of Words of a Rebel and began preparing to publish a magazine in the Armenian language.

Alexander Atabekian thought that Armenia was ripe for revolution, due to the conditions created by the Ottoman Empire's despotism and the exploitation of Armenian labour in Europe and America.

Alexander Atabekian called for the collectivisation of land and the establishment of self-governance in Armenia.

Alexander Atabekian published articles by the ARF, but supplemented them with his own criticisms of the authoritarianism and centralisation he'd experienced within the structures of Armenian political parties.

Alexander Atabekian ceased all of his publication activities after receiving news of the Hamidian massacres, which emotionally devastated him.

Together with other Armenian libertarians, Alexander Atabekian wrote a declaration to the London Congress of the Second International; he argued that European powers were complicit in the Hamidian massacres and declared the beginning of a social revolution in West Asia.

Alexander Atabekian was quickly appointed to head a field hospital in Baku, but he fell severely ill with typhoid fever and went on sick leave.

Alexander Atabekian recovered by early 1915 and was appointed to head a military hospital in Kars province, where his wife Ekaterina was working on a residency.

Alexander Atabekian travelled constantly to different fields during this period, witnessing the aftermath of battles in Karakilisa, Khnus and Mus.

Alexander Atabekian published an open letter to Kropotkin, in which he sharply criticised the Imperial Russian Army's attacks against the local Armenian and Kurdish populations, comparing them to the German occupation of Belgium.

Alexander Atabekian then called for anarchists to begin agitating for the construction of a new society through workers' self-management.

Alexander Atabekian placed his hopes in Moscow's "house committees", which had been established in order to protect the common interests of tenants and regulate landlords to ensure regular repairs and central heating.

Alexander Atabekian believed that these committees could be the means by which to fulfill people's needs and build a new social order, without political parties.

Alexander Atabekian considered cooperation to be a "law of life", stemming from the evolution of eusociality and human society, and saw it as essential to establishing socialist anarchism.

Alexander Atabekian defined the co-operative movement in opposition to the state, and believed that the abolition of the state would give way to a co-operative society based on mutual aid and voluntary labour.

Alexander Atabekian thus declared co-operative movement to be in opposition to state socialism, which he decried as imperialistic and limited by its own borders, whereas co-operative movement was internationalist in its methods.

Alexander Atabekian repeatedly attempted to recruit Peter Kropotkin to write for Pochin, but he refused each time, as he was focused on writing what would be his final work, Ethics: Origin and Development.

Alexander Atabekian nevertheless kept Kropotkin updated on the publication, receiving constructive criticism about an article that distinguished between territoriality and statehood, which Alexander Atabekian heavily revised before releasing.

On 24 October 1920, Alexander Atabekian was arrested by the Cheka, on charges of anti-Soviet agitation.

Alexander Atabekian was initially sentenced to two years in a labour camp, but this was quickly commuted to six months.

On 2 January 1921, Alexander Atabekian was prematurely released from prison, following a request for amnesty made by Peter Kropotkin to Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich.

Alexander Atabekian then tried to appeal for the lifting of the ban on Pochin, eventually receiving permission from Lev Kamenev to resume publication.

When Kropotkin fell ill with pneumonia, Alexander Atabekian travelled to Dmitrov to provide him with medical care.

Alexander Atabekian was joined by five other physicians, including Dmitry Pletnyov, who had been dispatched to treat Kropotkin by Lenin himself.

Emma Goldman and Alexander Atabekian Berkman arrived the following day, to belatedly pay their respects.

The Soviet authorities again briefly lifted the ban on the publication of Pochin, but it was banned again in 1922 and Alexander Atabekian's printing equipment was confiscated, bringing an end to his publishing career.

Alexander Atabekian was permitted by the authorities to continue his work with the Kropotkin Museum Committee throughout most of the period of the New Economic Policy.

Alexander Atabekian, who saw the committee as an organ of anarchist agitation, clashed with Kropotkin's widow Sofia, who wanted to avoid any conflict with the authorities.

In 1930, Alexander Atabekian suffered a stroke, which forced him into retirement.

Alexander Atabekian spent the last years of his life in his flat in Moscow, where he lived with his son, before dying on 5 December 1933.

Alexander Atabekian reported that in 1940, while working in a lagpunkt in Temnikov, he had treated an old anarchist called Alexei or Alexander Atabekian, who died of a heart attack towards the end of that year.

Today Alexander Atabekian is considered one of the foremost thinkers of post-classical anarchism in the former Russian Empire.

Information about Alexander Atabekian is scarce in the Russian state archives, which has resulted in some difficulty in forming a complete biographical picture of his life.

Some of Alexander Atabekian's papers have been preserved and archived by the International Institute of Social History, which collected his letters from Peter Kropotkin into the world's largest archive of Kropotkin's works.