1.

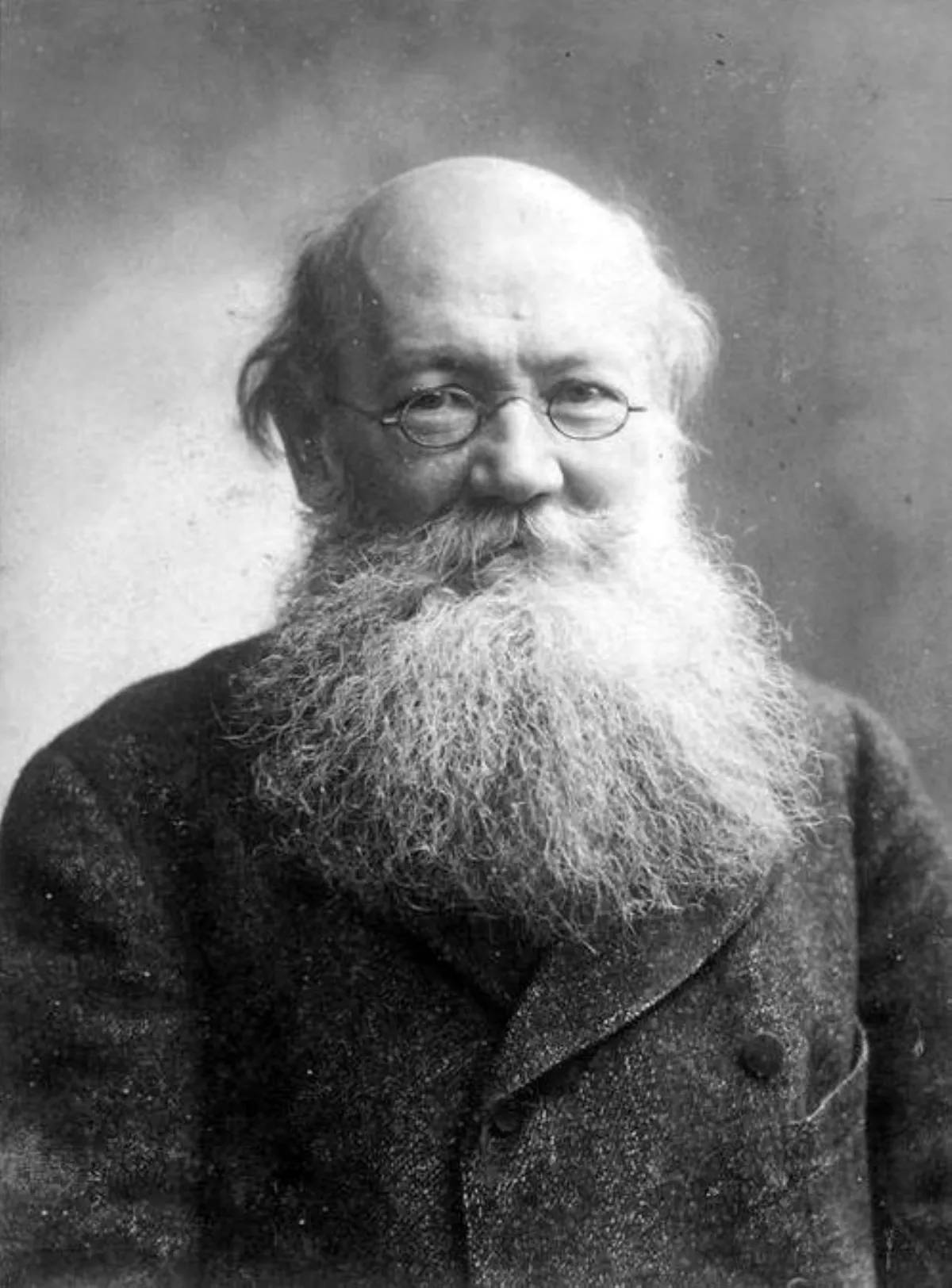

1. Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

1.

1. Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Peter Kropotkin was imprisoned for his activism in 1874 and managed to escape two years later.

Peter Kropotkin spent the next 41 years in exile in Switzerland, France and England.

Peter Kropotkin returned to Russia after the Russian Revolution in 1917, but he was disappointed by the Bolshevik state.

Peter Kropotkin was a proponent of the idea of decentralized communist society free from central government and based on voluntary associations of self-governing communities and worker-run enterprises.

Peter Kropotkin wrote many books, pamphlets and articles, the most prominent being The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories, and Workshops, with Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution being his principal scientific offering.

Peter Kropotkin was born in Moscow on 9 December 1842, in the Konyushennaya district.

Peter Kropotkin's father, Alexander, was a typical royal officer who owned serfs in three provinces and whose family descended from the princes of Smolensk.

Peter Kropotkin developed an enduring compassion for the estate's servants and serfs who cared for him and relayed stories of his mother's kindness.

Peter Kropotkin was raised in the family's Moscow mansion and an estate in Nikolskoye, Kaluga Oblast, outside Moscow.

At the age of eight, Peter Kropotkin attended Tsar Nicholas I's Royal Ball.

Peter Kropotkin joined the Page Corps as a teenager and began a 14-year epistolary relationship with his brother that charts his intellectual and emotional development.

Peter Kropotkin began his first underground revolutionary writings at the school, where he advocated for a Russian constitution.

Peter Kropotkin developed an interest in science, reading, and opera.

Peter Kropotkin developed a firm worldview of compassion for the poor and contrasted the pride and dignity of the yeoman peasant farmers against the indignities of serfdom.

Peter Kropotkin wrote approvingly of the cultivated Transbaikalia governor-general Boleslav Kukel, to whom Kropotkin reported.

Peter Kropotkin led a disguised reconnaissance expedition to find a direct route through Manchuria from Chita to Vladivostok the next year.

Peter Kropotkin explored the East Siberian Mountains in the north the year after.

Peter Kropotkin secured a promise from the governor-general to suspend the prisoners' death sentences, which was reneged upon.

Peter Kropotkin's time in Siberia taught him to appreciate peasant social organization and convinced him that administrative reform was an ineffectual means to improve social conditions.

Peter Kropotkin took a position with the Russian interior ministry with no duties.

Peter Kropotkin studied physics, math, and geography at the university.

Peter Kropotkin continued to develop a theory, which he considered his best scientific contribution, that the East Siberian mountains were part of a large plateau and not independent ridges.

Peter Kropotkin participated in an 1870 polar expedition plan that postulated the existence of what was later discovered as the Franz Josef Land Arctic archipelago.

In early 1871, he was commissioned to study the Ice Age in Scandinavian geography, in which Peter Kropotkin developed theories of the glaciation of Europe and the glacial lakes of its northeast.

Peter Kropotkin's father died later that year and Kropotkin inherited a wealthy estate in Tambov.

Peter Kropotkin turned down the Geographical Society's offer of its general secretary position, instead choosing work on his Ice Age data and interest in bettering the lives of peasants.

Peter Kropotkin was spurred by the 1871 Paris Commune and trial of Sergey Nechayev.

Likely at the encouragement of a Swiss extended family member and his own desire to see the socialist worker's movement, Peter Kropotkin set out to see Switzerland and Western Europe in February 1872.

Peter Kropotkin was quickly impressed and was instantly converted to anarchism by the group's egalitarianism and independence of expression, but narrowly missed meeting the leading anarchist, Bakunin, while there.

Back in St Petersburg, Kropotkin joined the Chaikovsky Circle, a group of revolutionaries that Kropotkin considered more educational than revolutionary in their activities.

Peter Kropotkin believed in the inevitability of Social revolution and the need for stateless social organization.

Peter Kropotkin viewed professionals as unlikely to forgo their privileges and judged them to not live societally useful lives.

Peter Kropotkin's program emphasized federated agrarian communes and a revolutionary party.

Peter Kropotkin emphasized living among commoners and using propaganda to focus mass dissatisfaction.

Peter Kropotkin had just filed his Ice Age report and had been recently elected president of the Geographical Society's Physical and Mathematical Department.

Peter Kropotkin visited Belgium and Zurich, where he met French geographer Elisee Reclus, who became a close friend.

Peter Kropotkin associated with the Jura Federation and began editing its publication.

Peter Kropotkin became the philosophy's most prominent proponent, despite not creating it.

Le Revolte published Peter Kropotkin's best known pamphlet, "An Appeal to the Young", in 1880.

Peter Kropotkin moved to Thonon-les-Bains, France, near Geneva, so that his wife could finish her Swiss education.

Peter Kropotkin would stay in England through 1917, settling in Harrow, London, apart from brief trips to other European countries.

Peter Kropotkin's first and only child, Alexandra Kropotkin, was born the next year.

Peter Kropotkin published multiple books over the next coming years including In Russian and French Prisons and The Conquest of Bread.

Peter Kropotkin joined the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Peter Kropotkin continued to contribute to Freedom but was no longer an editor.

Peter Kropotkin entered the United States and met John Most, Emma Goldman, and Benjamin Tucker.

Peter Kropotkin visited the United States again in 1901 at the invitation of the Lowell Institute to give lectures on Russian literature that were later published.

Peter Kropotkin published The Great French Revolution, The Terror in Russia, and Modern Science and Anarchism.

Peter Kropotkin exacerbated this by insisting, with returning to Russia, that Russians support the war as well.

Peter Kropotkin refused the Petrograd Provisional Government's offer of a cabinet seat.

Peter Kropotkin applied for a residence in Moscow in 1918, which was personally approved by Vladimir Lenin, head of the Soviet government.

Months later, finding life in Moscow difficult in his old age, Peter Kropotkin moved with his family to a friend's home in the nearby town of Dmitrov.

Peter Kropotkin met Lenin in Moscow and corresponded by mail to discuss political questions of the day.

Peter Kropotkin advocated for workers' cooperatives and argued against the Bolsheviks' hostage policy and centralization of authority, while simultaneously encouraging Western comrades to stop their governments' military interventions in Russia.

Peter Kropotkin's family refused an offer of a state funeral.

Peter Kropotkin critiqued what he considered to be the fallacies of the economic systems of feudalism and capitalism.

Peter Kropotkin believed they create poverty and artificial scarcity and promote privilege.

Peter Kropotkin argued that the tendencies for this kind of organization already exist, both in evolution and in human society.

Peter Kropotkin disagreed in part with the Marxist critique of capitalism, including the labor theory of value, believing there was no necessary link between work performed and the values of commodities.

Peter Kropotkin claimed this power was made possible by the state's protection of private ownership of productive resources.

However, Peter Kropotkin believed the possibility of surplus value was itself the problem, holding that a society would still be unjust if the workers of a particular industry kept their surplus to themselves, rather than redistributing it for the common good.

Peter Kropotkin believed that the mechanisms of the state were deeply rooted in maintaining the power of one class over another, and thus could not be used to emancipate the working class.

Peter Kropotkin believed that any post-revolutionary government would lack the local knowledge to organize a diverse population.

Rather than a centralized approach, Peter Kropotkin stressed the need for decentralized organization.

Peter Kropotkin summarized his thoughts in a 1919 letter to the workers of Western Europe, promoting the possibility of revolution, but warning against the centralized control in Russia, which he believed had condemned them to failure.

Peter Kropotkin wrote to Lenin in 1920, describing the desperate conditions that he believed to be the result of bureaucratic organization, and urging Lenin to allow for local and decentralized institutions.

In 1902, Peter Kropotkin published his book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, which gave an alternative view of animal and human survival.

Peter Kropotkin viewed cooperation and sociability among members of the same species as the best means to survive.

Biologist Stephen Jay Gould argued that Peter Kropotkin's view was consistent with modern biological understanding.

Peter Kropotkin agrees with Kropotkin's observations, noting that while Kropotkin did not deny the concept of competitive struggle, he believed that cooperative interactions were too often overlooked within it.

Peter Kropotkin did not deny the presence of competitive urges in humans, but did not consider them the driving force of human history.

Peter Kropotkin believed that seeking out conflict proved to be socially beneficial only in attempts to destroy injustice, as well as authoritarian institutions such as the state or the Russian Orthodox Church, which he saw as stifling human creativity and impeding human instinctual drive towards cooperation.

Peter Kropotkin claimed that the benefits arising from mutual organization incentivizes humans more than mutual strife.

Peter Kropotkin's hope was that in the long run, mutual organization would drive individuals to produce.

Peter Kropotkin believed that in a society that is socially, culturally, and industrially developed enough to produce all the goods and services it needs, there would be no obstacle, such as preferential distribution, pricing or monetary exchange, to prevent everyone to take what they need from the social product.

Peter Kropotkin supported the eventual abolition of money or tokens of exchange for goods and services.

Peter Kropotkin believed that Mikhail Bakunin's collectivist economic model was just a wage system by a different name and that such a system would breed the same type of centralization and inequality as a capitalist wage system.

Peter Kropotkin stated that it is impossible to determine the value of an individual's contributions to the products of labor and thought that anyone who was placed in a position of trying to make such determinations would wield authority over those whose wages they determined.

Peter Kropotkin's focus on local production led to his view that a country should strive for self-sufficiency by manufacturing its own goods and growing its own food, thus lessening the need to rely on imports.

Peter Kropotkin saw the origins of anarchism in Europe as found in various Christian movements, such as the Anabaptists and Hussites, mentioning figures such as the Italian Catholic bishop Marco Girolamo Vida and the German Anabaptist theologian Hans Denck.

Peter Kropotkin admired Christianity and Buddhism, along with the figures of Jesus Christ and Buddha and their ethical teachings.

Peter Kropotkin did not see that Christianity introduced anything new in its defense of brotherhood and mutual aid, but he did in forgiveness.

Peter Kropotkin saw the Christian God as an improvement over the pagan gods, whom he considered vengeful and to whom one should submit.

Peter Kropotkin spoke and acted in all things as he felt and believed and wrote.

Peter Kropotkin married Sofia, a Ukrainian Jewish student, in Switzerland in October 1878.

Peter Kropotkin's published story, "The Wife of Number 4,237", was based on her own experience with her husband at Clairvaux prison.

Peter Kropotkin created an archive in Moscow dedicated to his works before her death in 1941.

Peter Kropotkin was known for being exceptionally kind and for forgoing material comforts to live a revolutionary, principled life by example.

Much of Peter Kropotkin's impact was in his intellectual writings prior to 1914.

Peter Kropotkin had little influence on the Russian revolution, despite returning for it.

Peter Kropotkin is the namesake for a large town in the North Caucasus and a small town in Siberia.

The Peter Kropotkin Range he was first to cross in the Siberian Patom Highlands was named for him, as was a peak in East Antarctica.