1.

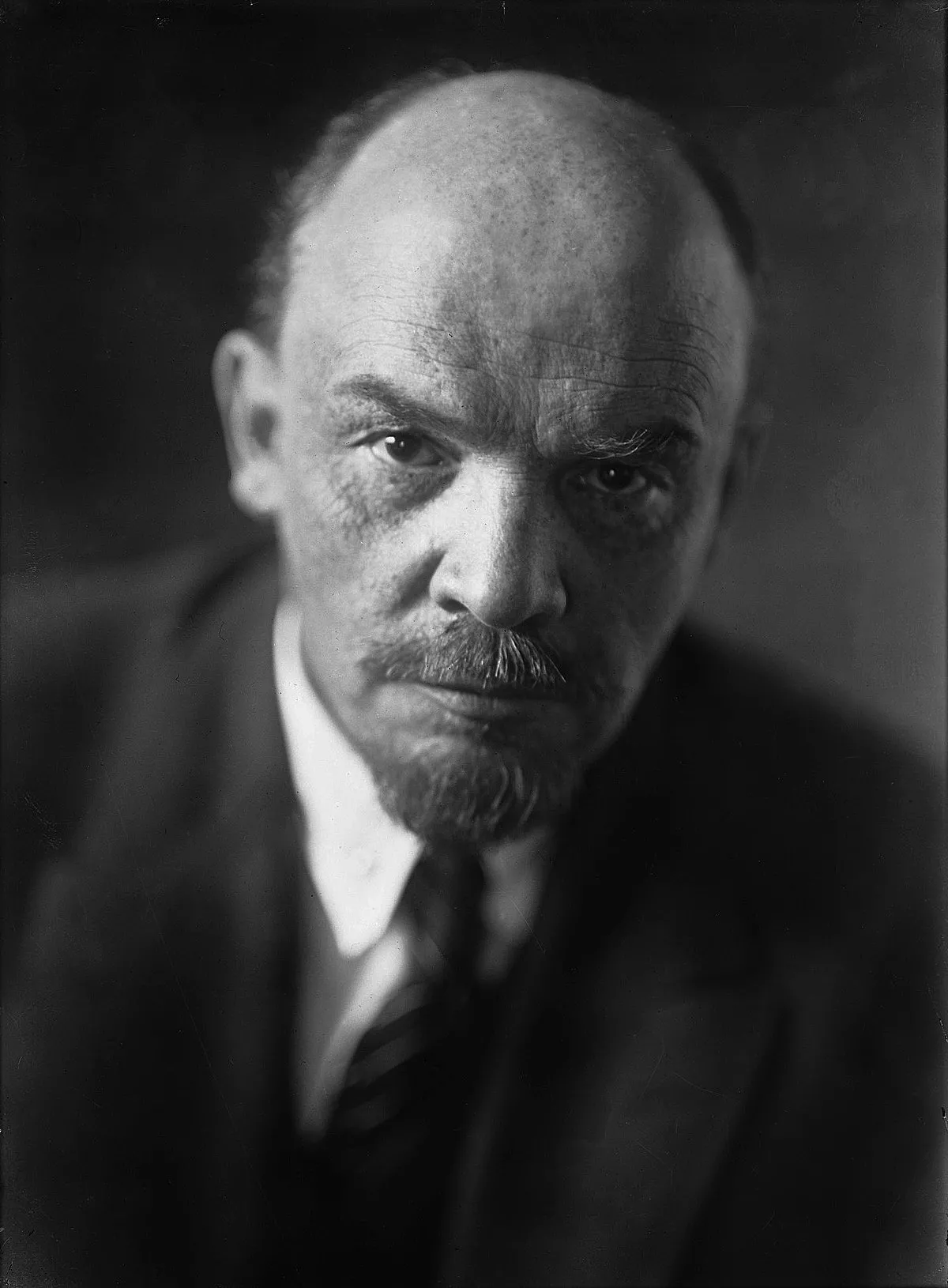

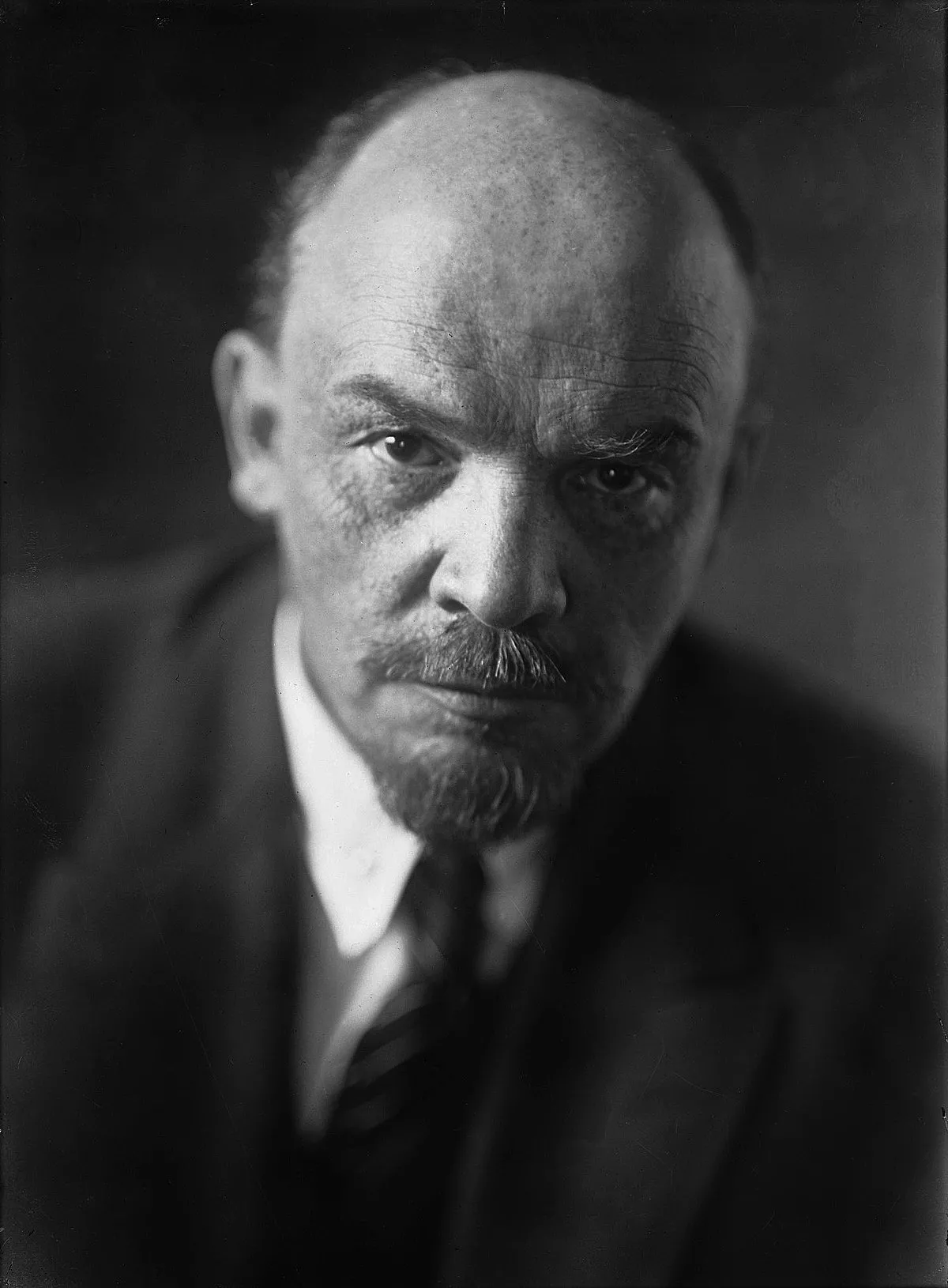

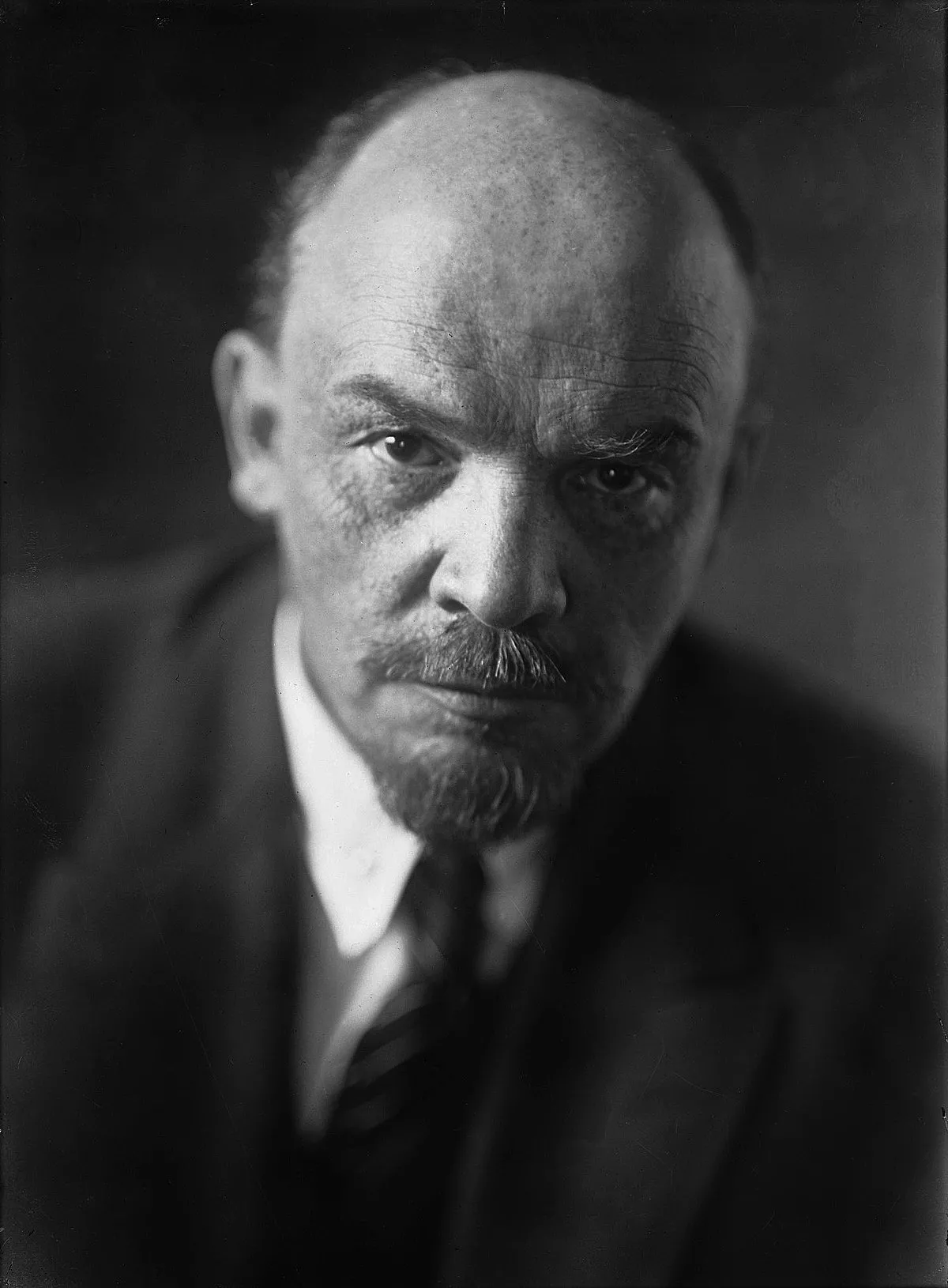

1. Vladimir Lenin was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until his death in 1924, and of the Soviet Union from 1922 until his death.

1.

1. Vladimir Lenin was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until his death in 1924, and of the Soviet Union from 1922 until his death.

Vladimir Lenin's government won the Russian Civil War and created a one-party state under the Communist Party.

Vladimir Lenin was expelled from Kazan Imperial University for participating in student protests, and earned a law degree before moving to Saint Petersburg in 1893 and becoming a prominent Marxist activist.

In 1897, Vladimir Lenin was arrested and exiled to Siberia for three years, after which he moved to Western Europe and became a leading figure in the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party.

Vladimir Lenin briefly returned to Russia during the Revolution of 1905, and during the First World War campaigned for its transformation into a Europe-wide proletarian revolution.

Vladimir Lenin's government abolished private ownership of land, nationalised major industry and banks, withdrew from the war by signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and promoted world revolution through the Communist International.

Vladimir Lenin was the posthumous subject of a pervasive personality cult within the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991.

Vladimir Lenin's father, Ilya Nikolayevich Ulyanov, was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church and baptised his children into it, although his mother, Maria Alexandrovna Ulyanova, a Lutheran by upbringing, was largely indifferent to Christianity, a view that influenced her children.

In January 1882, his dedication to education earned him the Order of Saint Vladimir Lenin, which bestowed on him the status of hereditary nobleman.

In January 1886, when Vladimir Lenin was 15, his father died of a brain haemorrhage.

Vladimir Lenin joined a revolutionary cell bent on assassinating the Tsar and was selected to construct a bomb.

The police arrested Vladimir Lenin and accused him of being a ringleader in the demonstration; he was expelled from the university, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs exiled him to his family's Kokushkino estate.

Vladimir Lenin's mother was concerned by her son's radicalisation, and was instrumental in convincing the Interior Ministry to allow him to return to the city of Kazan, but not the university.

Soviet historiography would later claim that, on his return to Kazan, Vladimir Lenin became involved with Nikolai Fedoseev's Marxist revolutionary circle, through which he would discover Karl Marx's 1867 book Capital.

However, it was not until 1888 that Fedoseev founded a Marxist study group, at which time Vladimir Lenin had already left the city; this meant that Vladimir Lenin and Fedoseev did not meet.

In September 1889, the Ulyanov family moved to the city of Samara, where Vladimir Lenin joined Alexei Sklyarenko's socialist discussion circle.

Vladimir Lenin had little interest in farm management, and his mother soon sold the land, keeping the house as a summer home.

Vladimir Lenin began to read the works of the Russian Marxist Georgi Plekhanov, agreeing with Plekhanov's argument that Russia was moving from feudalism to capitalism and so socialism would be implemented by the proletariat, or urban working class, rather than the peasantry.

Vladimir Lenin rejected the premise of the agrarian-socialist argument but was influenced by agrarian-socialists like Pyotr Tkachev and Sergei Nechaev and befriended several Narodniks.

In May 1890, Maria, who retained societal influence as the widow of a nobleman, persuaded the authorities to allow Vladimir Lenin to take his exams externally at the University of St Petersburg, where he obtained the equivalent of a first-class degree with honours.

Vladimir Lenin remained in Samara for several years, working first as a legal assistant for a regional court and then for a local lawyer.

Vladimir Lenin devoted much time to radical politics, remaining active in Sklyarenko's group and formulating ideas about how Marxism applied to Russia.

Vladimir Lenin wrote a paper on peasant economics; it was rejected by the liberal journal Russian Thought.

Vladimir Lenin began a romantic relationship with Nadezhda "Nadya" Krupskaya, a Marxist school teacher.

Vladimir Lenin authored a political tract criticising the Narodnik agrarian-socialists, What the "Friends of the People" Are and How They Fight the Social-Democrats; around 200 copies were illegally printed in 1894.

Vladimir Lenin proceeded to Paris to meet Marx's son-in-law Paul Lafargue and to research the Paris Commune of 1871, which he considered an early prototype for a proletarian government.

From his Marxist perspective, Vladimir Lenin argued that this Russian proletariat would develop class consciousness, which would in turn lead them to violently overthrow Tsarism, the aristocracy, and the bourgeoisie and to establish a dictatorship of the proletariat that would move toward socialism.

In February 1897, Vladimir Lenin was sentenced without trial to three years' exile in eastern Siberia.

Vladimir Lenin was granted a few days in Saint Petersburg to put his affairs in order and used this time to meet with the Social-Democrats, who had renamed themselves the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class.

Vladimir Lenin was initially posted to Ufa, but persuaded the authorities to move her to Shushenskoye, where she and Lenin married on 10 July 1898.

Vladimir Lenin finished The Development of Capitalism in Russia, his longest book to date, which criticised the agrarian-socialists and promoted a Marxist analysis of Russian economic development.

In July 1900, Vladimir Lenin left Russia for Western Europe; in Switzerland he met other Russian Marxists, and at a Corsier conference they agreed to launch the paper from Munich, where Vladimir Lenin relocated in September.

Vladimir Lenin first adopted the pseudonym Lenin in December 1901, possibly based on the Siberian River Lena; he often used the fuller pseudonym of N Lenin, and while the N did not stand for anything, a popular misconception later arose that it represented Nikolai.

Vladimir Lenin fell ill with erysipelas and was unable to take such a leading role on the Iskra editorial board; in his absence, the board moved its base of operations to Geneva.

Martov argued that party members should be able to express themselves independently of the party leadership; Vladimir Lenin disagreed, emphasising the need for a strong leadership with complete control over the party.

Vladimir Lenin's supporters were in the majority, and he termed them the "majoritarians" ; in response, Martov termed his followers the "minoritarians".

Arguments between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks continued after the conference; the Bolsheviks accused their rivals of being opportunists and reformists who lacked discipline, while the Mensheviks accused Vladimir Lenin of being a despot and autocrat.

Vladimir Lenin urged Bolsheviks to take a greater role in the events, encouraging violent insurrection.

Vladimir Lenin presented many of his ideas in the pamphlet Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution, published in August 1905.

Vladimir Lenin encouraged the party to seek out a much wider membership, and advocated the continual escalation of violent confrontation, believing both to be necessary for a successful revolution.

Alexander Bogdanov and other prominent Bolsheviks decided to relocate the Bolshevik Centre to Paris; although Vladimir Lenin disagreed, he moved to the city in December 1908.

Vladimir Lenin disliked Paris, lambasting it as "a foul hole", and while there he sued a motorist who knocked him off his bike.

Vladimir Lenin became very critical of Bogdanov's view that Russia's proletariat had to develop a socialist culture to become a successful revolutionary vehicle.

Furthermore, Bogdanov, influenced by Ernst Mach, believed that all concepts of the world were relative, whereas Vladimir Lenin stuck to the orthodox Marxist view that there was an objective reality independent of human observation.

Bogdanov and Vladimir Lenin holidayed together at Maxim Gorky's villa in Capri in April 1908; on returning to Paris, Vladimir Lenin encouraged a split within the Bolshevik faction between his and Bogdanov's followers, accusing the latter of deviating from Marxism.

In May 1908, Vladimir Lenin lived briefly in London, where he used the British Museum Reading Room to write Materialism and Empirio-criticism, an attack on what he described as the "bourgeois-reactionary falsehood" of Bogdanov's relativism.

Vladimir Lenin's factionalism began to alienate increasing numbers of Bolsheviks, including his former close supporters Alexei Rykov and Lev Kamenev.

Vladimir Lenin stayed in close contact with the RSDLP, which was operating in the Russian Empire, convincing the Duma's Bolshevik members to split from their parliamentary alliance with the Mensheviks.

In January 1913, Stalin, whom Vladimir Lenin referred to as the "wonderful Georgian", visited him, and they discussed the future of non-Russian ethnic groups in the Empire.

Vladimir Lenin was in Galicia when the First World War broke out.

The war pitted the Russian Empire against the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and due to his Russian citizenship, Vladimir Lenin was arrested and briefly imprisoned until his anti-Tsarist credentials were explained.

Vladimir Lenin was angry that the German Social Democratic Party was supporting the German war effort, which was a direct contravention of the Second International's Stuttgart resolution that socialist parties would oppose the conflict and saw the Second International as defunct.

Vladimir Lenin attended the Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915 and the Kienthal Conference in April 1916, urging socialists across the continent to convert the "imperialist war" into a continent-wide "civil war" with the proletariat pitted against the bourgeoisie and aristocracy.

In July 1916, Vladimir Lenin's mother died, but he was unable to attend her funeral.

In September 1917, Vladimir Lenin published Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, which argued that imperialism was a product of monopoly capitalism, as capitalists sought to increase their profits by extending into new territories where wages were lower and raw materials cheaper.

Vladimir Lenin believed that competition and conflict would increase and that war between the imperialist powers would continue until they were overthrown by proletariat revolution and socialism established.

Vladimir Lenin spent much of this time reading the works of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Ludwig Feuerbach, and Aristotle, all of whom had been key influences on Marx.

Vladimir Lenin still perceived himself as an orthodox Marxist, but he began to diverge from some of Marx's predictions about societal development; whereas Marx had believed that a "bourgeoisie-democratic revolution" of the middle classes had to take place before a "socialist revolution" of the proletariat, Lenin believed that in Russia the proletariat could overthrow the Tsarist regime without an intermediate revolution.

When Vladimir Lenin learned of this from his base in Switzerland, he celebrated with other dissidents.

Vladimir Lenin decided to return to Russia to take charge of the Bolsheviks but found that most passages into the country were blocked due to the ongoing conflict.

Vladimir Lenin organised a plan with other dissidents to negotiate a passage for them through Germany, with which Russia was then at war.

Vladimir Lenin publicly condemned both the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries, who dominated the influential Petrograd Soviet, for supporting the Provisional Government, denouncing them as traitors to socialism.

Vladimir Lenin began arguing for a Bolshevik-led armed insurrection to topple the government, but at a clandestine meeting of the party's central committee this idea was rejected.

Vladimir Lenin initially turned down the leading position of Chairman, suggesting Trotsky for the job, but other Bolsheviks insisted and ultimately Vladimir Lenin relented.

Vladimir Lenin argued that the election did not reflect the people's will, claiming the electorate was unaware of the Bolsheviks' programme, and that candidacy lists were outdated, having been drawn up before the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries split from the Socialist-Revolutionaries.

Vladimir Lenin rejected repeated calls, including from some Bolsheviks, to establish a coalition government with other socialist parties.

At their 7th Congress in March 1918, the Bolsheviks changed their name from the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party to the Russian Communist Party, as Vladimir Lenin wanted to distance his group from the increasingly reformist German Social Democratic Party and emphasize its goal of a communist society.

Vladimir Lenin was the most significant figure in this governance structure, being Chairman of Sovnarkom and sitting on the Council of Labour and Defence, the Central Committee, and the Politburo.

In November 1917, Vladimir Lenin issued the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia, granting non-Russian ethnic groups the right to secede and form independent nation-states.

In October 1917, Vladimir Lenin decreed an eight-hour workday for all Russians.

Vladimir Lenin issued the Decree on Popular Education, guaranteeing free, secular education for all children, and a decree establishing state orphanages.

Vladimir Lenin's Russia became the first country to legalize first-trimester abortion on demand.

In November 1917, Vladimir Lenin issued the Decree on Workers' Control, calling on workers to form elected committees to monitor their enterprise's management.

Vladimir Lenin deemed this impractical and argued for the nationalization of only large-scale capitalist enterprises, allowing smaller businesses to operate privately until they could be successfully nationalized.

Vladimir Lenin opposed the Left Communists' syndicalist approach, arguing in June 1918 for centralized economic control, rather than factory-level worker control.

Internationally, many socialists condemned Vladimir Lenin's regime, highlighting the lack of widespread political participation, popular consultation, and industrial democracy.

Vladimir Lenin believed that ongoing war would create resentment among war-weary Russian troops, to whom he had promised peace, and that these troops and the advancing German Army threatened both his own government and the cause of international socialism.

Vladimir Lenin proposed a three-month armistice in his Decree on Peace of November 1917, which was approved by the Second Congress of Soviets and presented to the German and Austro-Hungarian governments.

Vladimir Lenin argued that the territorial losses were acceptable if it ensured the survival of the Bolshevik-led government.

At this point, Vladimir Lenin finally convinced a small majority of the Bolshevik Central Committee to accept the Central Powers' demands.

Vladimir Lenin blamed this on the kulaks, or wealthier peasants, who allegedly hoarded the grain that they had produced to increase its financial value.

Vladimir Lenin repeatedly emphasised the need for terror and violence in overthrowing the old order and ensuring the success of the revolution.

Vladimir Lenin never witnessed this violence or participated in it first-hand, and publicly distanced himself from it.

Vladimir Lenin's published articles and speeches rarely called for executions, but he regularly did so in his coded telegrams and confidential notes.

From July 1922, intellectuals deemed to be opposing the Bolshevik government were exiled to inhospitable regions or deported from Russia altogether; Vladimir Lenin personally scrutinised the lists of those to be dealt with in this manner.

In May 1922, Vladimir Lenin issued a decree calling for the execution of anti-Bolshevik priests, causing between 14,000 and 20,000 deaths.

Vladimir Lenin expected Russia's aristocracy and bourgeoisie to oppose his government but believed that the numerical superiority of the lower classes, coupled with the Bolsheviks' organizational skills, would ensure a swift victory.

Vladimir Lenin did not anticipate the intensity of the violent opposition that ensued.

Vladimir Lenin tasked Trotsky with forming the Red Army, with Trotsky organizing a Revolutionary Military Council in September 1918 and serving as chairman until 1925.

Vladimir Lenin allowed former Tsarist officers to serve in the Red Army, monitored by military councils.

Some historians believe Vladimir Lenin sanctioned the killings, while others, like James Ryan, argue there is "no reason" to believe so.

Vladimir Lenin viewed the execution as necessary, likening it to the execution of Louis XVI during the French Revolution.

Various senior Bolsheviks wanted these absorbed into the Russian state; Vladimir Lenin insisted that national sensibilities should be respected, but reassured his comrades that these nations' new Communist Party administrations were under the de facto authority of Sovnarkom.

Vladimir Lenin saw this as a revival of the Second International, which he had despised, and formulated his own rival international socialist conference to offset its impact.

Accordingly, the Bolsheviks dominated proceedings, with Vladimir Lenin subsequently authoring a series of regulations that meant that only socialist parties endorsing the Bolsheviks' views were permitted to join Comintern.

The Second Congress of the Communist International opened in Petrograd's Smolny Institute in July 1920, representing the last time that Vladimir Lenin visited a city other than Moscow.

Vladimir Lenin's predicted world revolution did not materialise, as the Hungarian communist government was overthrown, and the German Marxist uprisings suppressed.

Vladimir Lenin deemed the unions to be superfluous in a "workers' state", but Lenin disagreed, believing it best to retain them; most Bolsheviks embraced Lenin's view in the 'trade union discussion'.

Vladimir Lenin declared that the mutineers had been misled by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and foreign imperialists, calling for violent reprisals.

In February 1921, Vladimir Lenin introduced a New Economic Policy to the Politburo; he convinced most senior Bolsheviks of its necessity and it passed into law in April.

Vladimir Lenin termed this "state capitalism", and many Bolsheviks thought it to be a betrayal of socialist principles.

Vladimir Lenin biographers have often characterised the introduction of the NEP as one of his most significant achievements, and some believe that had it not been implemented then Sovnarkom would have been quickly overthrown by popular uprisings.

Vladimir Lenin called for a mass electrification project of Russia, the GOELRO plan, which began in February 1920; Vladimir Lenin's declaration that "communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country" was widely cited in later years.

Vladimir Lenin hoped that by allowing foreign corporations to invest in Russia, Sovnarkom would exacerbate rivalries between the capitalist nations and hasten their downfall; he tried to rent the oil fields of Kamchatka to an American corporation to heighten tensions between the US and Japan, who desired Kamchatka for their empire.

Between 1920 and 1926, twenty volumes of Vladimir Lenin's Collected Works were published; some material was omitted.

Vladimir Lenin was visited at the Kremlin by Armand, who was in increasingly poor health.

Vladimir Lenin sent her to a sanatorium in Kislovodsk in the Northern Caucasus to recover, but she died there in September 1920 during a cholera epidemic.

Vladimir Lenin's body was transported to Moscow, where a visibly grief-stricken Lenin oversaw her burial beneath the Kremlin Wall.

Vladimir Lenin became seriously ill by the latter half of 1921, experiencing hyperacusis, insomnia, and regular headaches.

Vladimir Lenin began to contemplate the possibility of suicide, asking both Krupskaya and Stalin to acquire potassium cyanide for him.

Vladimir Lenin was concerned by the survival of the Tsarist bureaucratic system in Soviet Russia, particularly during his final years.

Vladimir Lenin recommended that Stalin be removed from the position of General Secretary of the Communist Party, deeming him ill-suited for the position.

In December 1922, Stalin took responsibility for Vladimir Lenin's regimen, being tasked by the Politburo with controlling who had access to him.

Vladimir Lenin was increasingly critical of Stalin; while Vladimir Lenin was insisting that the state should retain its monopoly on international trade during mid-1922, Stalin was leading other Bolsheviks in unsuccessfully opposing this.

Vladimir Lenin saw this as an expression of Great Russian ethnic chauvinism by Stalin and his supporters, instead calling for these nation-states to join Russia as semi-independent parts of a greater union, which he suggested be called the Union of Soviet Republics of Europe and Asia.

In March 1923, Vladimir Lenin had a third stroke and lost his ability to speak; that month, he experienced partial paralysis on his right side and began exhibiting sensory aphasia.

On 21 January 1924, Vladimir Lenin fell into a coma and died later that day at age 53.

Vladimir Lenin's funeral took place the following day, when his body was carried to Red Square, accompanied by martial music, where assembled crowds listened to a series of speeches before the corpse was placed into the vault of a specially erected mausoleum.

Against Krupskaya's protestations, Vladimir Lenin's body was embalmed to preserve it for long-term public display in the Red Square mausoleum.

Vladimir Lenin's sarcophagus was replaced in 1940 and again in 1970.

Vladimir Lenin defined socialism as "an order of civilized co-operators in which the means of production are socially owned", and believed that this economic system had to be expanded until it could create a society of abundance.

Vladimir Lenin believed that all workers throughout the country would voluntarily join to enable the state's economic and political centralisation.

Vladimir Lenin adapted his ideas according to changing circumstances, including the pragmatic realities of governing Russia amid war, famine, and economic collapse.

Vladimir Lenin believed that although Russia's economy was dominated by the peasantry, the presence of monopoly capitalism in Russia meant that the country was sufficiently materially developed to move to socialism.

Vladimir Lenin did not question old Marxist scripture, he merely commented, and the comments have become a new scripture.

Vladimir Lenin opposed liberalism, what, according to Dmitri Volkogonov, was "a mark" of his general antipathy toward liberty as a value, and believing that liberalism's freedoms were fraudulent because it did not free labourers from capitalist exploitation.

Vladimir Lenin declared that "Soviet government is many millions of times more democratic than the most democratic-bourgeois republic", the latter of which was simply "a democracy for the rich".

Vladimir Lenin regarded his dictatorship of the proletariat as democratic because, he claimed, it involved the election of representatives to the soviets, workers electing their own officials, and the regular rotation and involvement of all workers in the administration of the state.

However, as the Soviet state faced international isolation by the end of its victory in the Civil War and adopted NEP policies, which were seen as a source of danger for the regime, Vladimir Lenin stated that his government could "promise neither freedom nor democracy" until the threat of war or attack on the Soviet state was gone, just as any other government, he said, would act "in war", intending the denial of political freedoms to be provisional.

Vladimir Lenin was an internationalist and a keen supporter of world revolution, deeming national borders to be an outdated concept and nationalism a distraction from class struggle.

Vladimir Lenin believed that in a socialist society, the world's nations would inevitably merge and result in a single world government.

Vladimir Lenin believed that this socialist state would need to be a centralised, unitary one, and regarded federalism as a bourgeois concept.

Vladimir Lenin supported wars of national liberation, accepting that such conflicts might be necessary for a minority group to break away from a socialist state, because socialist states are not "holy or insured against mistakes or weaknesses".

On taking power, Vladimir Lenin called for the dismantling of the bonds that had forced minority ethnic groups to remain in the Russian Empire and espoused their right to secede but expected them to reunite immediately in the spirit of proletariat internationalism.

Vladimir Lenin was willing to use military force to ensure this unity, resulting in armed incursions into the independent states that formed in Ukraine, Georgia, Poland, Finland, and the Baltic states.

Vladimir Lenin saw himself as a man of destiny and firmly believed in the righteousness of his cause and his own ability as a revolutionary leader.

Historian and biographer Robert Service asserted that Vladimir Lenin had been an intensely emotional young man, who exhibited strong hatred for the Tsarist authorities.

In Volkogonov's view, Vladimir Lenin accepted Marxism as "absolute truth", and accordingly acted like "a religious fanatic".

Biographer Christopher Read suggested that Vladimir Lenin was "a secular equivalent of theocratic leaders who derive their legitimacy from the [perceived] truth of their doctrines, not popular mandates".

Vladimir Lenin was nevertheless an atheist and a critic of religion, believing that socialism was inherently atheistic; he thus considered Christian socialism a contradiction in terms.

Vladimir Lenin's life became the history of the Bolshevik movement.

Service stated that Vladimir Lenin could be "moody and volatile", and Pipes deemed him to be "a thoroughgoing misanthrope", a view rejected by Read, who highlighted many instances in which Vladimir Lenin displayed kindness, particularly toward children.

Vladimir Lenin could be "venomous in his critique of others", exhibiting a propensity for mockery, ridicule, and ad hominem attacks on those who disagreed with him.

Vladimir Lenin ignored facts that did not suit his argument, abhorred compromise, and very rarely admitted his own errors.

Vladimir Lenin refused to change his opinions, until he rejected them completely, after which he would treat the new view as if it was just as unchangeable.

Vladimir Lenin showed no sign of sadism or of personally desiring to commit violent acts, but he endorsed the violent actions of others and exhibited no remorse for those killed for the revolutionary cause.

Vladimir Lenin was annoyed at what he perceived as a lack of conscientiousness and discipline among the Russian people, and from his youth had wanted Russia to become more culturally European and Western.

The Vladimir Lenin who seemed externally so gentle and good-natured, who enjoyed a laugh, who loved animals and was prone to sentimental reminiscences, was transformed when class or political questions arose.

Vladimir Lenin despised untidiness, always keeping his work desk tidy and his pencils sharpened, and insisted on total silence while he was working.

Conversely, various Marxist observers, including Western historians Hill and John Rees, argued against the view that Vladimir Lenin's government was a dictatorship, viewing it instead as an imperfect way of preserving elements of democracy without some of the processes found in liberal democratic states.

Busts or statues of Vladimir Lenin were erected in almost every village, and his face adorned postage stamps, crockery, posters, and the front pages of Soviet newspapers Pravda and Izvestia.

The Order of Vladimir Lenin was established as one of the country's highest decorations.

Various biographers have stated that Vladimir Lenin's writings were treated in a manner akin to religious scripture within the Soviet Union, while Pipes added that "his every opinion was cited to justify one policy or another and treated as gospel".

Under Stalin's regime, Vladimir Lenin was portrayed as a close friend of Stalin's who had supported Stalin's bid to be the next Soviet leader.

In late 1991, amid the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russian President Boris Yeltsin ordered the Vladimir Lenin archive be removed from Communist Party control and placed under the control of a state organ, the Russian Centre for the Preservation and Study of Documents of Recent History, at which it was revealed that over 6,000 of Vladimir Lenin's writings had gone unpublished.

Socialist states following Vladimir Lenin's ideas appeared in various parts of the world during the 20th century, forming into variants such as Stalinism, Maoism, Juche, Ho Chi Minh Thought, and Castroism.