1.

1. In parallel to his literary career, Alexandru Macedonski was a civil servant, notably serving as prefect in the Budjak and Northern Dobruja during the late 1870s.

1.

1. In parallel to his literary career, Alexandru Macedonski was a civil servant, notably serving as prefect in the Budjak and Northern Dobruja during the late 1870s.

Alexandru Macedonski's biography was marked by an enduring interest in esotericism, numerous attempts to become recognized as an inventor, and an enthusiasm for cycling.

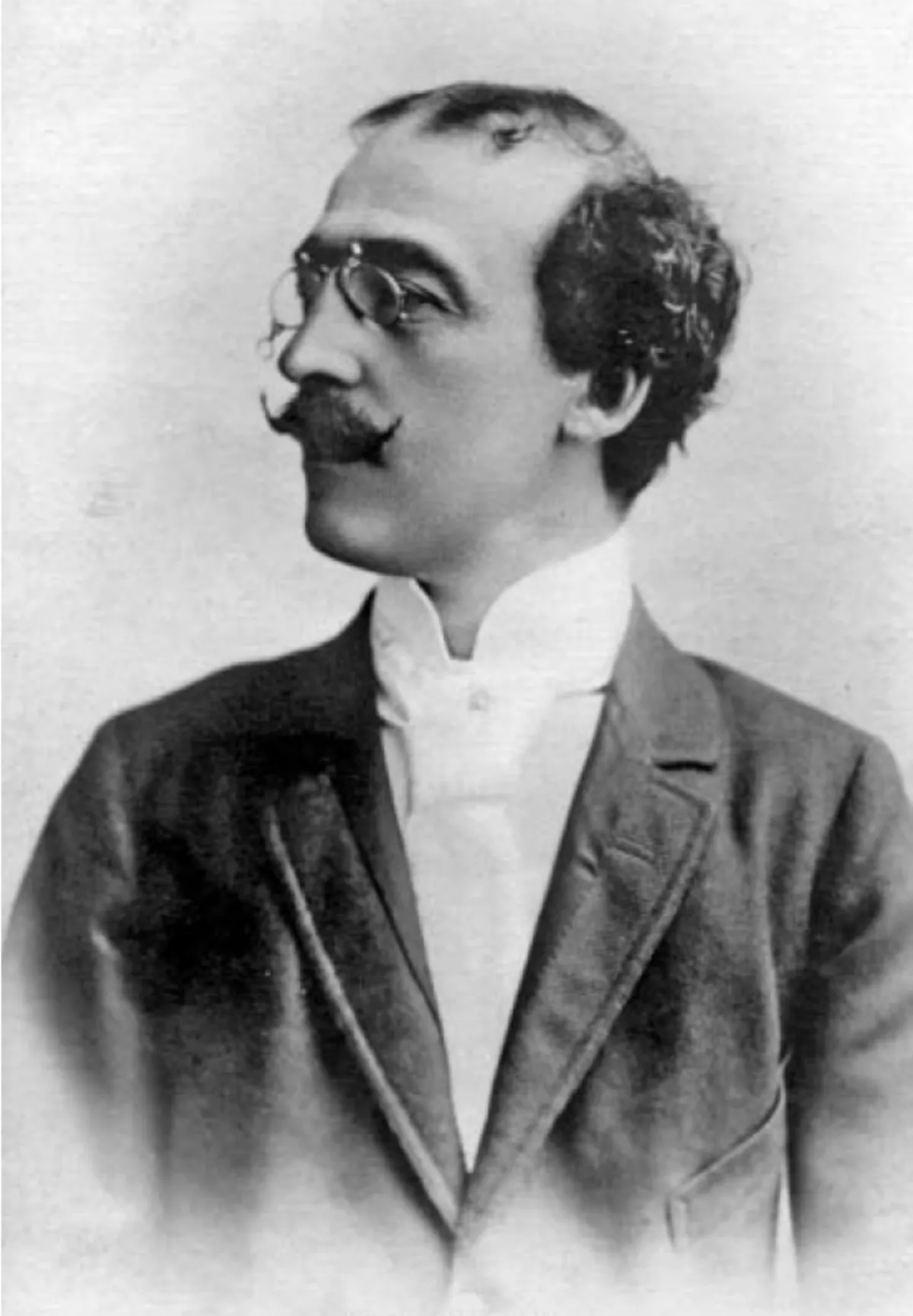

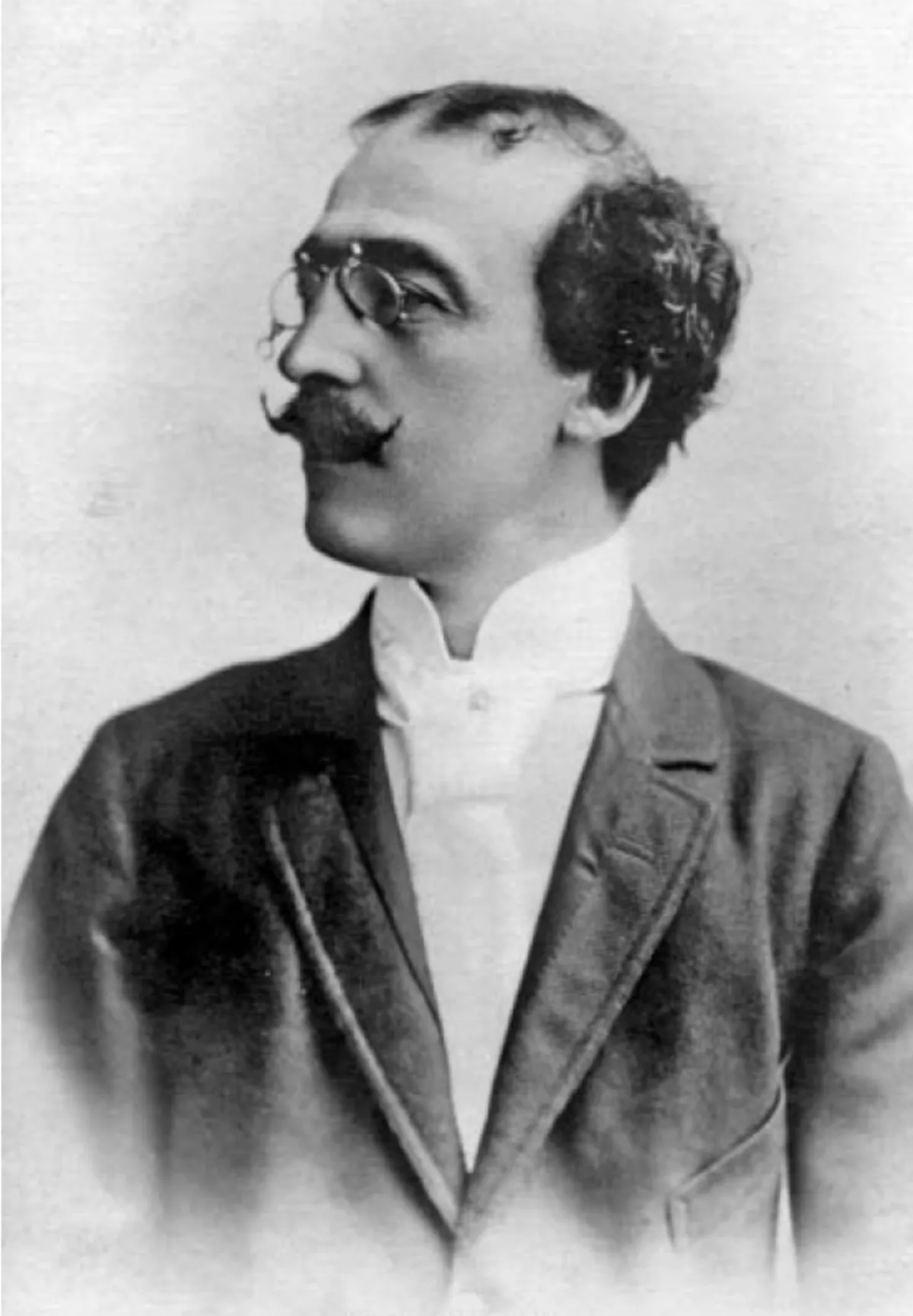

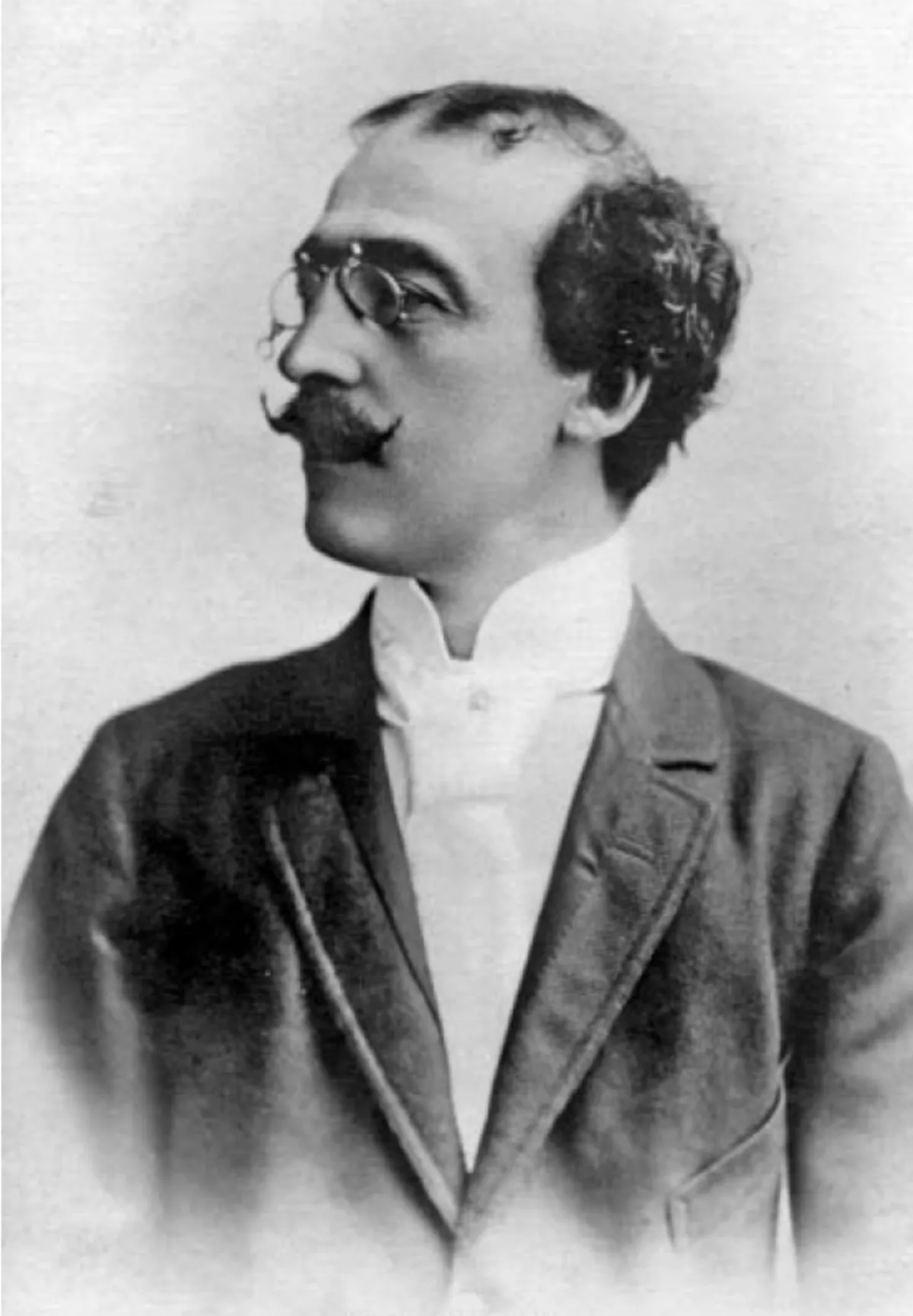

The scion of a political and aristocratic family, the poet was the son of General Alexandru Macedonski, who served as Defense Minister, and the grandson of 1821 rebel Dimitrie Macedonski.

Dimitrie married Zoe, the daughter an ethnic Russian or Polish officer; their son, the Russian-educated Alexandru Macedonski, climbed in the military and political hierarchy, joining the unified Land Forces after his political ally, Alexander John Cuza, was elected Domnitor and the two Danubian Principalities became united Romania.

Alexandru Macedonski was attending the Carol I High School in Craiova and, according to his official record, graduated in 1867.

Alexandru Macedonski's father had by then become known as an authoritarian commander, and, during his time in Targu Ocna, faced a mutiny which only his wife could stop by pleading with the soldiers.

Alexandru Macedonski left Romania in 1870, traveling through Austria-Hungary and spending time in Vienna, before visiting Switzerland and possibly other countries; according to one account, it was here that he may have first met his rival poet Mihai Eminescu, at a time a Viennese student.

Alexandru Macedonski's visit was meant to be preparation for entering the University of Bucharest, but he spent much of his time in the bohemian environment, seeking entertainment and engaging in romantic escapades.

Alexandru Macedonski claimed to have attended college lectures in these cities, and to have spent significant time studying at Pisa University, but this remains uncertain.

Alexandru Macedonski eventually returned to Bucharest, where he entered the Faculty of Letters.

In 1874, back in Craiova, Alexandru Macedonski founded a short-lived literary society known as Junimea, a title which purposefully or unwittingly copied that of the influential conservative association with whom he would later quarrel.

In March 1875, Alexandru Macedonski was arrested on charges of defamation or sedition.

Alexandru Macedonski was taken to Bucharest's Vacaresti Prison and confined there for almost three months.

In 1875, after the National Liberal Ion Emanuel Florescu was assigned the post of Premier by Carol, Alexandru Macedonski embarked on an administrative career.

Ghica and Alexandru Macedonski remained close friends until Ghica's 1882 death.

Alexandru Macedonski spoke at the Romanian Atheneum, presenting his views on the state of Romanian literature.

Still determined to pursue a career in the press, Alexandru Macedonski founded a string of unsuccessful magazines with patriotic content and titles such as Vestea, Dunarea, Fulgerul and, after 1880, Tarara.

Alexandru Macedonski had previously refused to be made comptroller in Putna County, believing such an appointment to be beneath his capacity, and had lost a National Liberal appointment in Silistra when Southern Dobruja was granted to the Principality of Bulgaria.

Florescu parted with the group soon after, due to a disagreement with Alexandru Macedonski, and was later attacked by the latter for allegedly accumulating academic posts.

An early success for the new journal was the warm reception it received from Vasile Alecsandri, a Romantic poet and occasional Junimist whom Alexandru Macedonski idolized at the time, and the collaboration of popular memoirist Gheorghe Sion.

At around that time, Alexandru Macedonski had allegedly begun courting actress Aristizza Romanescu, who rejected his advances, leaving him unenthusiastic about love matters and unwilling to seek female company.

In parallel, Alexandru Macedonski used the magazine to publicize his disagreement with the main Junimist voice, Convorbiri Literare.

Calinescu asserts that, although Alexandru Macedonski later claimed to have always been facing poverty, his job in the administration, coupled with other sources of revenue, ensured him a comfortable existence.

Again moving away from liberalism, Alexandru Macedonski sought to make himself accepted by Junimea and Maiorescu.

Alexandru Macedonski consequently attended the Junimea sessions, and gave a public reading of Noaptea de noiembrie, the first publicized piece in his lifelong Nights cycle.

Alexandru Macedonski took distance from Alecsandri's style, publishing a "critical analysis" of his poetry in one issue of Literatorul.

At the other end of the political and cultural spectrum, Alexandru Macedonski faced opposition from the intellectuals attracted to socialism, in particular Contemporanul editors Constantin Mille and Ioan Nadejde, with whom he was engaged in an extended polemic.

In July 1883, Alexandru Macedonski undertook one of his most controversial anti-Junimist actions.

Ever since that moment, Alexandru Macedonski has generally been believed to be Duna, and as a result, was faced with much criticism from both readers and commentators.

The circumstances in which this took place rose suspicion of foul play; on this grounds, Alexandru Macedonski was ridiculed by his former friend Zamfirescu in the journal Romania Libera, which left him embittered.

Alexandru Macedonski would marry off or simply mate some of his disciples with aging and rich women, and then he would squeeze out their assets.

Alexandru Macedonski became opposed to Carol I, who, in 1881, had been granted the Crown of the Romanian Kingdom.

An enthusiastic promoter of the sport, Alexandru Macedonski joined fellow poet Constantin Cantilli on a marathon, pedaling from Bucharest across the border into Austria-Hungary, all the way down to Brasov.

Alexandru Macedonski returned with a new volume of poetry, Excelsior, and founded Liga Ortodoxa, a magazine noted for hosting the debut of Tudor Arghezi, later one of the most celebrated figures in Romanian literature.

Alexandru Macedonski commended his new protege for reaching "the summit of poetry and art" at "an age when I was still prattling verses".

Liga Ortodoxa hosted articles against Caragiale, which Alexandru Macedonski signed with the pseudonym Sallustiu.

Alexandru Macedonski was shocked to note that Ghenadie had given up his own defense.

Traian Demetrescu, who recorded his visits with Alexandru Macedonski, recalled his former mentor being opposed to his positivist take on science, claiming to explain the workings of the Universe in "a different way", through "imagination", but taking an interest in Camille Flammarion's astronomy studies.

Alexandru Macedonski was determined to interpret death through parapsychological means, and, in 1900, conferenced at the Atheneum on the subject Sufletul si viata viitoare.

Later, Nikita Alexandru Macedonski registered the invention of nacre-treated paper, which is sometimes attributed to his father.

In parallel, Alexandru Macedonski returned to the public scene, founding Forta Morala magazine.

Alexandru Macedonski refused to withdraw his support for the cause even after Caragiale sued Caion, but Forta Morala soon went out of print.

Alexandru Macedonski registered more success in 1906, when his Thalassa was published, as Le Calvaire de feu, by Edward Sansot's Paris-based publishing house.

Alexandru Macedonski sent a paper on astronomy subjects to be reviewed by the Societe Astronomique de France, of which he subsequently became a member.

Alexandru Macedonski introduced himself to an Italophone public, when two of his sonnets were published by Poesia, the magazine of Futurist theorist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

Alexandru Macedonski was actively seeking to establish his reputation in French theater, reading his new play to a circle which included Louis de Gonzague Frick and Florian-Parmentier, while, at home, newspapers reported rumors that his work was going to be staged by Sarah Bernhardt's company.

Alexandru Macedonski's efforts were largely fruitless, and, accompanied by his son Alexis, the poet left France, spent some time in Italy, and eventually returned to Romania.

Tudor Vianu, who cites contemporary statements by Dragoslav, concludes that, upon arrival, Alexandru Macedonski was enthusiastically received by a public who had missed him.

Around that time, Alexandru Macedonski collaborated with the Iasi-based moderate Symbolist magazine Versuri si Proza.

Alexandru Macedonski is said to have spent part of his time at Kubler loudly mocking the traditionalist poets who gathered at an opposite table.

Alexandru Macedonski himself was seated on a throne designed by Alexis, and adopted a dominant pose.

Alexandru Macedonski further alienated public opinion during the Romanian Campaign, when the Central Powers armies entered southern Romania and occupied Bucharest.

Alexandru Macedonski's stance was interpreted as collaborationism by his critics.

Alexandru Macedonski faced problems after the Romanian government resumed its control over Bucharest, and during the early years of Greater Romania.

Alexandru Macedonski envisaged running in the 1918 election for a seat in the new Parliament, but never registered his candidature.

Alexandru Macedonski's health deteriorated from heart disease, which is described by Vianu as an effect of constant smoking.

Likewise, Vianu notes, Alexandru Macedonski had a tendency for comparing nature with the artificial, the result of this being a "document" of his values.

Alexandru Macedonski's language alternated neologisms with barbarisms, many of which were coined by him personally.

Almost all periods of Alexandru Macedonski's work reflect, in whole or in part, his public persona and the polemics he was involved in.

However, literary researcher Adrian Marino proposes that Alexandru Macedonski was one of the first modern authors to illustrate the importance of "dialectic unity" through his views on art, in particular by having argued that poetry needed to be driven by "an idea".

In Vianu's perspective, Alexandru Macedonski's stance is dominated by a mixture of nostalgia, sensuality, lugubrious-grotesque imagery, and "the lack of bashfulness for antisocial sentiments" which complements his sarcasm.

George Calinescu himself believes Alexandru Macedonski to have been "fundamentally a spiritual man with lots of humor", speculating that he was able to see the "uselessness" of his own scientific ventures.

Critics note that, while Alexandru Macedonski progressed from one stage to the other, his work fluctuated between artistic accomplishment and mediocrity.

Tudor Vianu believes "failure in reaching originality" and reliance on "soppy-conventional attributes of the day" to be especially evident wherever Alexandru Macedonski tried to emulate epic poetry.

Calinescu writes that, while Alexandru Macedonski's work is largely inferior to that of his Junimist rival, it forms the best "reply" ever conceived within their common setting.

The imprint of Romanticism and such other sources was evident in Prima verba, which groups pieces that Alexandru Macedonski authored in his early youth, the earliest of them being written when he was just twelve.

Part of the text was an ironic treatment of youth in liberal professions, an attitude which Alexandru Macedonski fitted in his emerging anti-bourgeois discourse.

Noaptea de noiembrie opens with a violent condemnation of his adversaries, and sees Alexandru Macedonski depicting his own funeral.

The poem is commended by Calinescu, who notes that, in contrast to the "apparently trivial beginning", the main part, where Alexandru Macedonski depicts himself in flight over the Danube, brings the Romanian writer close to the accomplishments of Dante Aligheri.

Traian Demetrescu thus noted that Alexandru Macedonski cherished the works of French Naturalists and Realists such as Gustave Flaubert and Emile Zola.

Around the time of its completion, Alexandru Macedonski was working on a similarly loose adaptation of William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, which notably had the two protagonists die in each other's arms.

In parallel, Alexandru Macedonski was using poetry to carry out his polemics.

Also during that stage, Alexandru Macedonski was exploring the numerous links between Symbolism, mysticism and esotericism.

Also at that stage, Alexandru Macedonski began publishing the "instrumentalist" series of his Symbolist poems.

Alexandru Macedonski's fate is changed by a shipwreck, during which a girl, Caliope, reaches the island's shore.

Alexandru Macedonski's manuscript is written in ink of several colors, which, he believed, was to help readers get a full sense of its meaning.

Particularly during the 1890s, Alexandru Macedonski was a follower of Edgar Allan Poe and of Gothic fiction in general, producing a Romanian version of Poe's Metzengerstein story, urging his own disciples to translate other such pieces, and adopting "Gothic" themes in his original prose.

Indebted to Jules Verne and H G Wells, Macedonski wrote a number of science fiction stories, including the 1913 Oceania-Pacific-Dreadnought, which depicts civilization on the verge of a crisis.

Alexandru Macedonski was by then interested in the development of cinema, and authored a silent film screenplay based on Comment on devient riche et puissant.

Late in his life, Alexandru Macedonski had come to reject Symbolist tenets, defining them as "imbecilities" designed for "the uncultured".

Calinescu writes that, by then, Alexandru Macedonski was "obsessed" with the Divine Comedy.

Alexandru Macedonski identifies with his hero, Dante Aligheri, and formulates his own poetic testament while identifying World War I Romania with the medieval Republic of Florence.

The Orient, viewed as the space of serenity, is believed by Alexandru Macedonski to be peopled by toy-like women and absent opium-smokers, and to be kept orderly by a stable meritocracy.

Alexandru Macedonski repeatedly expressed the thought that, unlike his contemporaries, posterity would judge him a great poet.

One of these texts, the 1886 essay Poeti si critici, spoke of Macedonski as having "vitiated" poetry, a notion he applied to Constantin D Aricescu and Aron Densusianu.

The pictorial and joyous elements in Alexandru Macedonski's poems were serving to inspire Stamatiad, Eugeniu Stefanescu-Est and Horia Furtuna.

Many of Alexandru Macedonski's most devoted disciples, whom he himself had encouraged, have been rated by various critics as secondary or mediocre.

Two years after her father's death, Anna Alexandru Macedonski married poet Mihail Celarianu.

Alexandru Macedonski's admirers were writing poetry about him as early as 1874, and, in 1892, Cincinat Pavelescu published a rhapsodizing portrait of Macedonski as "the Artist".

In contrast, traditionalist poet Alexandru Vlahuta authored an 1889 sketch story in which Macedonski is the object of derision.

Alexandru Macedonski's work was analyzed and popularized by a new generation of critics, among them Vianu and George Calinescu.

Alexandru Macedonski's prose influenced younger writers such as Angelo Mitchievici and Anca Maria Mosora.

In neighboring Moldova, Alexandru Macedonski influenced the Neosymbolism of Aureliu Busuioc.

Alexandru Macedonski's poems had a sizable impact on Romania's popular culture.

Alongside other writers who visited Terasa Otetelesanu, Alexandru Macedonski was notably portrayed the drawings of celebrated Romanian artist Iosif Iser.

Alexandru Macedonski is depicted in a 1918 lithograph by Jean Alexandru Steriadi, purportedly Steriadi's only Symbolist work.

Thalassa, Le Calvaire de feu inspired a series of reliefs, designed by Alexis Alexandru Macedonski and hosted in his father's house in Dorobanti.