1.

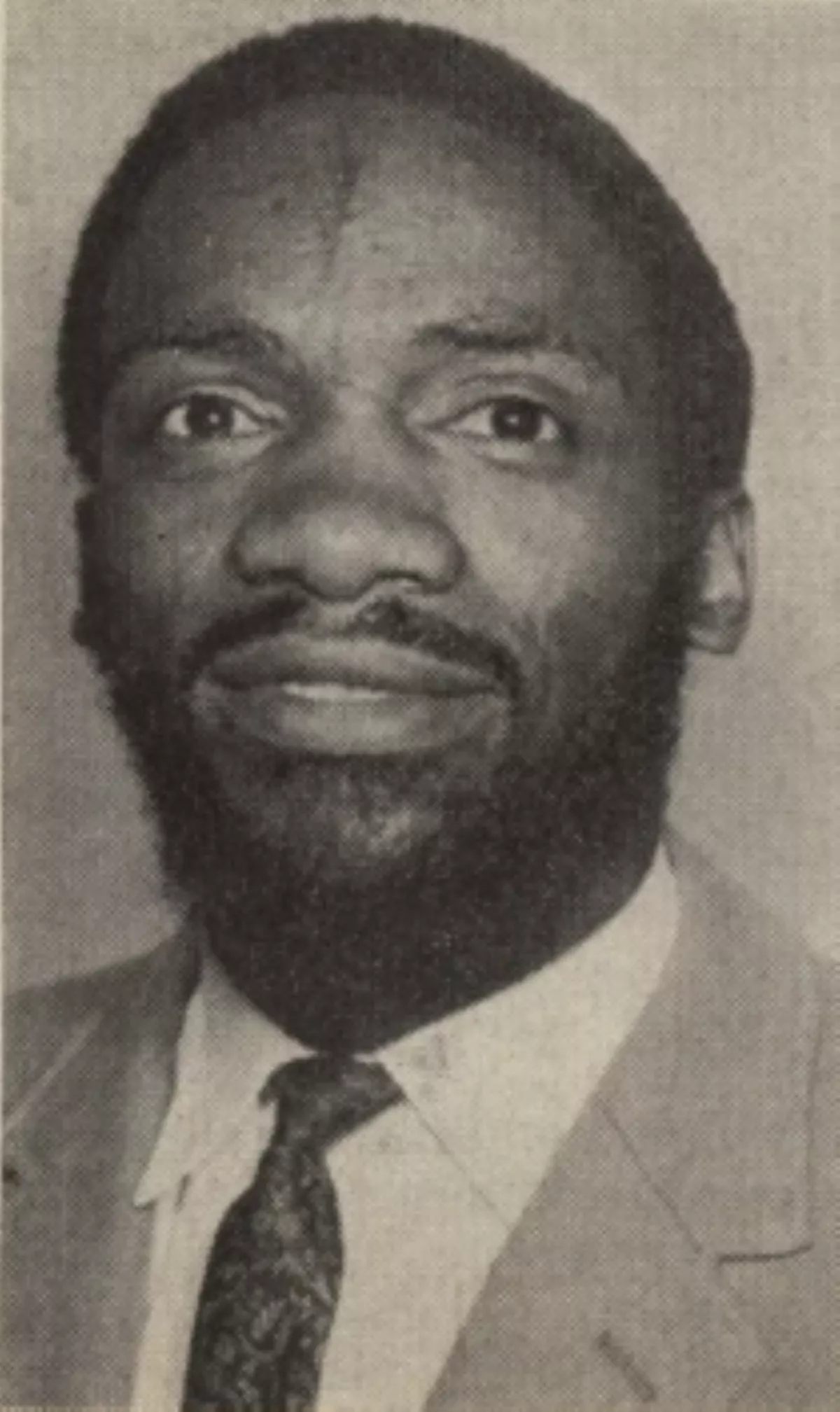

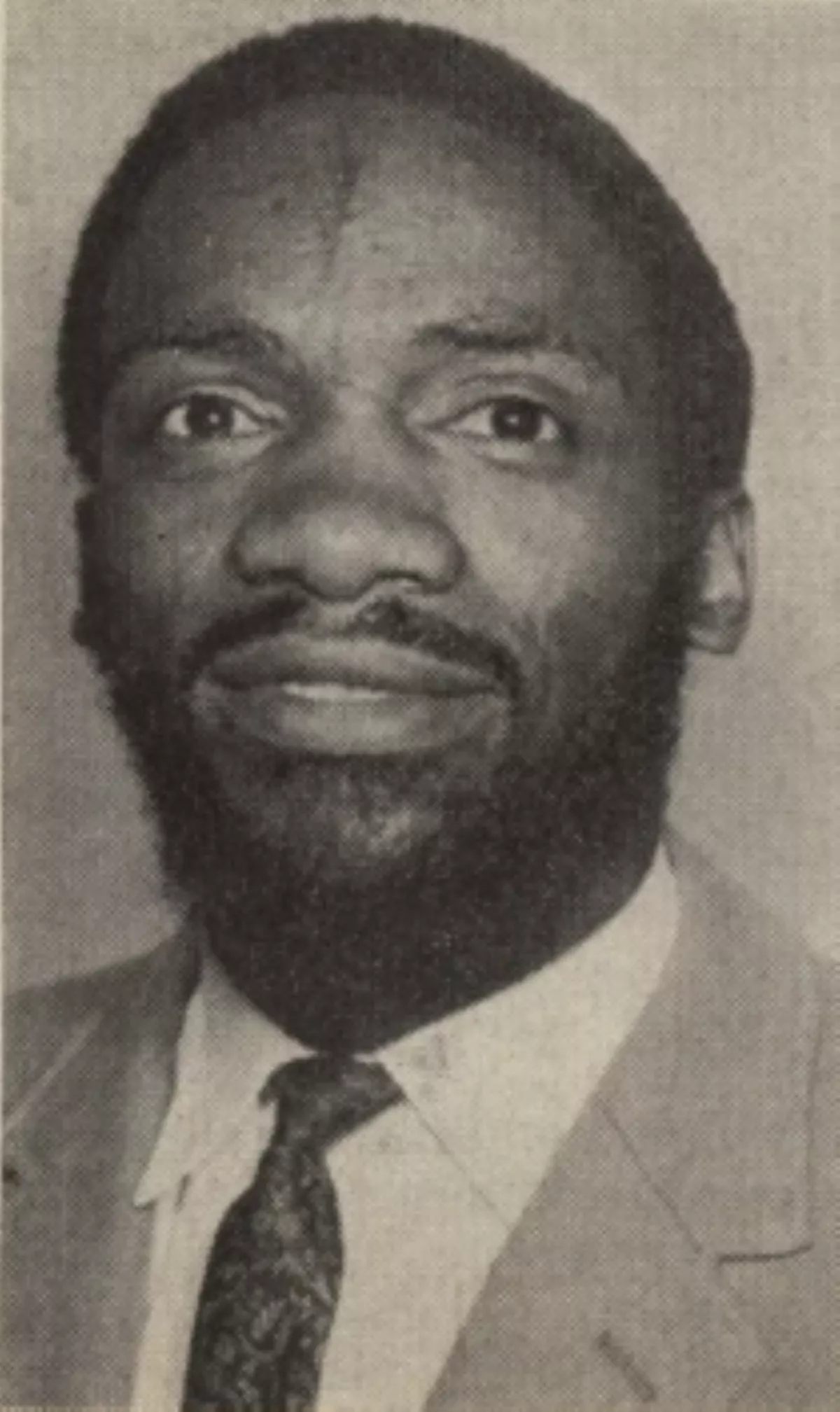

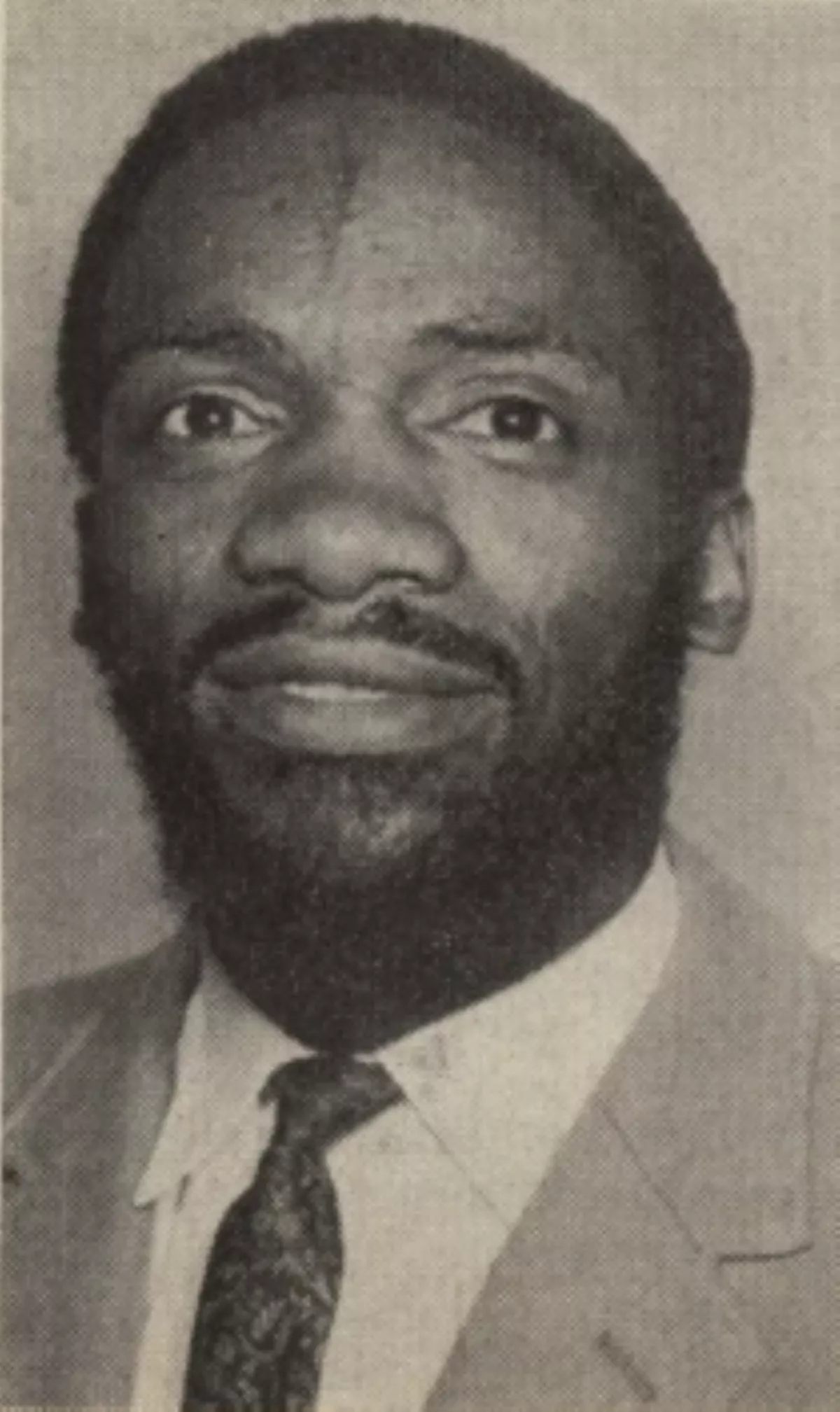

1. Archibald Boyce Monwabisi Mafeje, commonly known as Archie Mafeje, was a South African anthropologist and activist.

1.

1. Archibald Boyce Monwabisi Mafeje, commonly known as Archie Mafeje, was a South African anthropologist and activist.

Archie Mafeje became a professor at various universities in Europe, North America, and Africa.

Archie Mafeje spent most of his career away from apartheid South Africa after he was blocked from teaching at UCT in 1968.

Archie Mafeje was particularly interested in land ownership and resource allocation issues, and argued that apartheid was built on a foundation of unjust land distribution and exploitation.

Archie Mafeje's work has influenced debates about African identity, autonomy, and independence.

Archibald Boyce Monwabisi Archie Mafeje was born on 30 March 1936 in Gubenxa, a remote village in the Ngcobo, Cape Province, Union of South Africa.

The Archie Mafeje isiduko comes from the Mpondomise, a Xhosa sub-ethnic group.

Archie Mafeje's father, Bennett, was the headmaster of Gubenxa Junior School, and his mother, Frances Lydia, was a teacher.

Archie Mafeje's parents were married in Langa, Cape Town, in 1934, before moving to Gubenxa, and later to the village of Ncambele in Tsolo.

In 1951 and 1952, Archie Mafeje completed his Junior Certificate at Nqabara Secondary School, a Methodist missionary school in Willowvale.

Archie Mafeje then matriculated in 1954 to Healdtown Comprehensive School in Fort Beaufort, a Methodist missionary with a list of alumni that includes Nelson Mandela and Robert Sobukwe.

Bongani Nyoka asserts that at Healdtown, Archie Mafeje became a radical atheist.

Archie Mafeje joined the Fort Hare Native College, a black university in Eastern Cape, in mid-1955 to study zoology, but he left after one year.

Archie Mafeje enrolled in the University of Cape Town in 1957, joining a minority of less than twenty non-white students on a campus of five thousand.

Archie Mafeje recalled that as a biology student in the late 1950s, he was taught the same [racist attitudes] by my white professors who nonetheless regarded him as "the other".

Francis Wilson, Fikile Bam and Archie Mafeje held political debates with other students at the "Freedom Square" below the Jameson Hall steps.

Nonetheless, Archie Mafeje's friends recalled that certain SOYA members found his intellectualism and preference for theoretical argument irritating because they believed he spent too much time "hobnobbing with whites".

Archie Mafeje used his knowledge of the Xhosa language and his father's connections to complete fieldwork in Langa between November 1960 and September 1962.

Archie Mafeje published part of this independently, and then Monica Wilson wrote a scientific paper based on the work titled Langa: A Study of Social Groups in an African Township, published as a book by Oxford University Press in 1963.

On 16 August 1963, Archie Mafeje spoke to a group that was gathered illegally and as a result was detained.

Archie Mafeje was fined and sent back to Cape Town instead of being prosecuted.

Archie Mafeje then moved to the UK initially as a research assistant at the University of Cambridge after being recommended by Wilson, but then completed a Doctor of Philosophy in social anthropology under Audrey Richards' supervision at King's College, University of Cambridge, in the late 1960s.

Archie Mafeje sought to return to UCT and applied for a senior lecturer post that UCT widely advertised in August 1967.

Archie Mafeje was unanimously offered a post as senior lecturer of social anthropology by the UCT Council.

Archie Mafeje was scheduled to start in May 1968, but the UCT Council withdrew Archie Mafeje's employment offer because the government threatened to cut funding and impose sanctions on UCT should it appoint him.

Ntsebeza asserts that, in the eyes of the students, the Archie Mafeje affair was not about Archie Mafeje, the individual, but rather about academic freedom and the autonomy of universities.

Archie Mafeje left after having disagreements with the administration on his draft syllabus of a foundation course on Africa called Problematizing Africa.

In 2003, UCT officially apologised to Archie Mafeje and offered him an honorary doctorate, but he did not respond to UCT's offer.

Archie Mafeje assumed a senior lecturer position in 1969, before becoming a full professor and the head of the sociology department, at the University of Dar Es Salaam in Tanzania.

Archie Mafeje did not return following a spat with the principal of the university and the dean of the faculty.

Between 1972 and 1975, Archie Mafeje chaired the Urban Development and Labour Studies Program at the International Institute of Social Studies in the Netherlands where he first met Shahida El-Baz, an academic and activist from Egypt who would later become his wife.

In 1973, at age 36, Archie Mafeje was appointed Queen Juliana Professor of Development Sociology and Anthropology by a Parliamentary act.

Archie Mafeje became a Dutch citizen and was appointed one of the Queen's lords with his name engraved on the prestigious blue pages of the Dutch National Directorate, becoming one of the first Africans to receive this honour.

Archie Mafeje was appointed Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at American University in Cairo in 1978 until 1990, and later in 1994.

Archie Mafeje was known for not giving his students tests, as he preferred essays on which he could make significant comments.

Archie Mafeje joined the Southern Africa Political Economy Series Trust in Harare, Zimbabwe, in 1991 on a visiting fellowship.

However, Archie Mafeje left in the same year due to a disagreement with the trust's executive director, Ibbo Mandaza, who wanted Archie Mafeje to keep 09:00 to 17:00 office hours.

In 1992, Archie Mafeje began a one-year visiting fellowship at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, in the US.

Archie Mafeje's wife said his life was made a living hell by racist Namibians within and outside the university to the extent that he required a bodyguard.

The experience severely impacted Archie Mafeje, and departed Namibia and returned to AUC in Cairo in 1994.

Archie Mafeje served as a senior fellow and guest lecturer at several North American, European, and African colleges and research centres.

In 2000, Archie Mafeje returned to South Africa after spending more than 30 years in exile to take the position of a Senior Research Fellow at the African Renaissance Centre at the National Research Foundation.

Archie Mafeje married Nomfundo Noruwana, a nurse, in 1961, and the two of them had a son, Xolani, in 1962.

Archie Mafeje married Shahida El-Baz in 1977; they had a daughter, Dana.

Archie Mafeje had to convert to Islam before they were wed because El-Baz was Muslim.

Archie Mafeje was a keen observer of Egyptian socio-political and economic changes; although he disliked Anwar Sadat for persecuting intellectuals, he was never personally involved in Egyptian politics.

Archie Mafeje was perceived by his peers as an independent thinker who was extraordinarily "difficult", and by his students as someone who did "not suffer fools gladly".

Archie Mafeje was famous for saying, "If in the face of apparent defeat, we cannot maximise our gains, then it is imperative that we minimise our losses".

Archie Mafeje died in Pretoria on 28 March 2007, and was buried next to his parents in Ncambele.

Archie Mafeje was part of SOYA and the African Peoples' Democratic Union of Southern Africa which later became the Non-European Unity Movement.

Archie Mafeje was particularly interested in land ownership and resource allocation issues, and argued that the apartheid system was built on a foundation of unjust land distribution and exploitation.

Archie Mafeje advocated for a more holistic approach to land and agrarian reform that recognised rural communities' diverse needs and interests.

Archie Mafeje argued that land reform should not be imposed from above but should instead be based on a participatory and democratic process that involved local communities.

Archie Mafeje emphasised the need for agrarian reform to be linked to broader social and economic transformation, including women's empowerment and promotion of sustainable agricultural practices.

Archie Mafeje was critical of neoclassical economic theories that, according to him, underpinned many of Africa's land and agricultural policies, which he argued were often based on flawed assumptions and failed to account for the complexities of African societies.

Archie Mafeje argued that poverty was not simply a matter of individuals lacking sufficient income, but a result of unequal distribution of wealth and power embedded in colonial and postcolonial social structures.

Therefore, Archie Mafeje believed that a real solution to poverty alleviation entailed a fundamentally restructuring, rather than providing charity or aid to the poor.

Archie Mafeje argued that only through a comprehensive program of land reform, agrarian reform, and economic redistribution could the underlying causes of poverty be addressed.

Archie Mafeje held Lenin and Mao in great esteem, but not Trotsky, whom Archie Mafeje accused of being a Eurocentrist.

Archie Mafeje believed that socialism in one country is insufficient to bring about genuine social transformation and needs to be pursued at regional and continental levels.

Archie Mafeje argued that socialism could not be achieved in isolation but must be part of a broader movement towards social justice and equality across Africa.

Archie Mafeje's ideology was rooted in a Marxist and anti-colonial perspective.

Archie Mafeje believed that Africa's underdevelopment was a direct result of its history of colonialism, which had created a dependent and unequal relationship between Africa and colonial powers in the West.

Archie Mafeje advocated for an alternative approach to development rooted in self-reliance and African unity.

Archie Mafeje argued that African countries needed to prioritise their own development needs and resources rather than rely on foreign aid and external development models.

Archie Mafeje believed that African countries needed to work together to achieve economic and political independence rather than compete with one another for Western aid and investment.

In exile, Archie Mafeje shared animosity with white South African Communist Party members, including Joe Slovo, Dan O'Meara and Duncan Innes.

Archie Mafeje accused them of "white superiority" and "ideological superiority", although Duncan Innes was integral to the Archie Mafeje affair protest in 1968.

Archie Mafeje published highly influential sociological essays and books in the fields of development and agrarian studies, economic models, politics, and the politics of social scientific knowledge production in Africa.

Archie Mafeje is considered one of the leading contemporary African anthropologists; however, he is considered more of a critical theorist than a field researcher.

Archie Mafeje demanded that imperialist and Western ideals be eliminated from Black African anthropology, which led to an examination of the discipline's founding principles and the methods by which academics approached the study of the attributed other.

Archie Mafeje was critical of the mainstream development theories of his time, which he saw as perpetuating this unequal relationship.

Archie Mafeje was critical of Africa's academic and intellectual establishment, which he saw as being too closely aligned with colonial power structures.

Archie Mafeje believed that African scholars and intellectuals needed to challenge dominant Western perspectives and develop their own theories and knowledge systems grounded in African life's realities.

Archie Mafeje had a critical view of ethnography, which he believed to be a product of colonialism and imperialism.

Archie Mafeje argued that ethnography, as a tool of Western social science, tended to create a distorted and exoticised image of African societies and was often used to justify colonial domination and exploitation.

Archie Mafeje believed that ethnographic studies should be approached with caution and scepticism, and that researchers should be aware of the power dynamics and historical context in which they operate.

Archie Mafeje argued for a more self-reflexive and critical approach to ethnography, one that acknowledges the researcher's limitations and biases and is attentive to the political and economic structures that shape social relations.

Archie Mafeje advocated for an alternative approach to ethnography that involved a greater emphasis on dialogue and collaboration between researcher and subject, as well as a more reflexive and critical approach to the role of the researcher in shaping the research process and outcomes.

Archie Mafeje was one of the first academics to dedicate himself to deconstructing the ideology of tribalism.

Archie Mafeje was critical of liberal functionalism, a theoretical framework that posits that societies work best when organised around the efficient performance of specialised tasks by individuals and institutions.

Archie Mafeje argued that this perspective was often used to justify preserving colonial power structures and economic systems that were exploitative and oppressive of African people.

Archie Mafeje was particularly critical of the idea that the key to development in Africa was the creation of strong, centralised states and the imposition of a Western-style legal and economic system.

Archie Mafeje argued that this approach failed to consider the diversity of African societies and the importance of indigenous forms of governance and economic organisation.

Archie Mafeje argues that the idea of tribalism is a colonial construct used to justify domination and exploitation, and perpetuate divisions and inequalities in postcolonial African societies.

Archie Mafeje explores the historical context in which the concept emerged and how it has been used to maintain power structures and suppress dissent.

Archie Mafeje argues that African societies are not based on rigid tribal affiliations but rather on fluid and flexible relationships between different groups.

Archie Mafeje critiques the idea of cultural essentialism, which suggests that there is an essential and unchanging African culture.

Archie Mafeje argues that culture is not static, but constantly changing and adapting to new situations.

Archie Mafeje's work seeks to challenge and subvert the dominant narratives about African societies and their supposed tribalism.

Archie Mafeje engaged in a series of debates and polemics with scholars such as Ruth First, Harold Wolpe, Ali Mazrui, Achille Mbembe, and Sally Falk Moore, who was an anthropologist and Chair at Harvard University.

Archie Mafeje wrote an article critiquing the apartheid government's response to the uprising and broadly analysing the political and economic conditions that led to it.

Archie Mafeje argued that the uprising manifested broader social and economic tensions in South Africa, and that the apartheid government's response only exacerbated these tensions.

Archie Mafeje believed that Mafeje placed too much emphasis on the state's actions and neglected the black community's agency and resistance.

Harold Wolpe and Archie Mafeje had a famous debate in the 1970s about the nature of the South African economy and the role of migrant labour in its development.

Archie Mafeje argued that Wolpe's view was based on a static and reductionist understanding of the rural economy and failed to consider the agency and creativity of rural people.

Archie Mafeje argues for the need to "indigenise" knowledge production by grounding it in African experiences and perspectives, rather than relying solely on Western theoretical frameworks.

Archie Mafeje, in turn, disagreed with Mbembe's characterisation of the concept, arguing that the pessimism he observed was not inherent in African culture, but a product of the historical and political context in which Africa had developed.

Archie Mafeje argued that African intellectuals should focus on analysing and critiquing these structural factors, rather than attributing Africa's problems to cultural or racial factors.

Additionally, Archie Mafeje delivered a lecture in 2000 titled "African Modernities and Colonialism's Predicaments: Reflections on Achille Mbembe's 'On the Postcolony'", in which he criticised Mbembe's ideas about the nature of power in postcolonial African states and his use of the concept of the "postcolony".

Archie Mafeje argued that societies were based on class relations and that social stratification existed in the pre-colonial era.

Archie Mafeje challenged the dominant view that African societies were essentially egalitarian and lacked social differentiation as in Europe.

Archie Mafeje argued that the forms of social stratification in pre-colonial Africa were not comparable to the class structures of Europe.

Archie Mafeje emphasised that it was important to understand the specific ways in which power and authority were distributed in African societies.

Archie Mafeje was considered part of the first generation of indigenous researchers, who rejected colonialist and neo-colonialist interpretations of Africa.

Archie Mafeje maintains that knowledge production is always influenced by social, economic, and political factors, and that any claim to universal truth must be scrutinised in this context.

Archie Mafeje argues that he is advocating for a more nuanced and reflexive approach to knowledge production that considers the social and historical contexts in which it occurs.

Archie Mafeje is perceived as one of Africa's most prominent intellectual and remembered for mixing his scholarship and experience as an oppressed black person.

Archie Mafeje was elected a Fellow of the African Academy of Sciences in 1986.

Archie Mafeje received an Honorary Life Membership of CODESRIA in 2003 and was named CODESRIA Distinguished Fellow in 2005.