1.

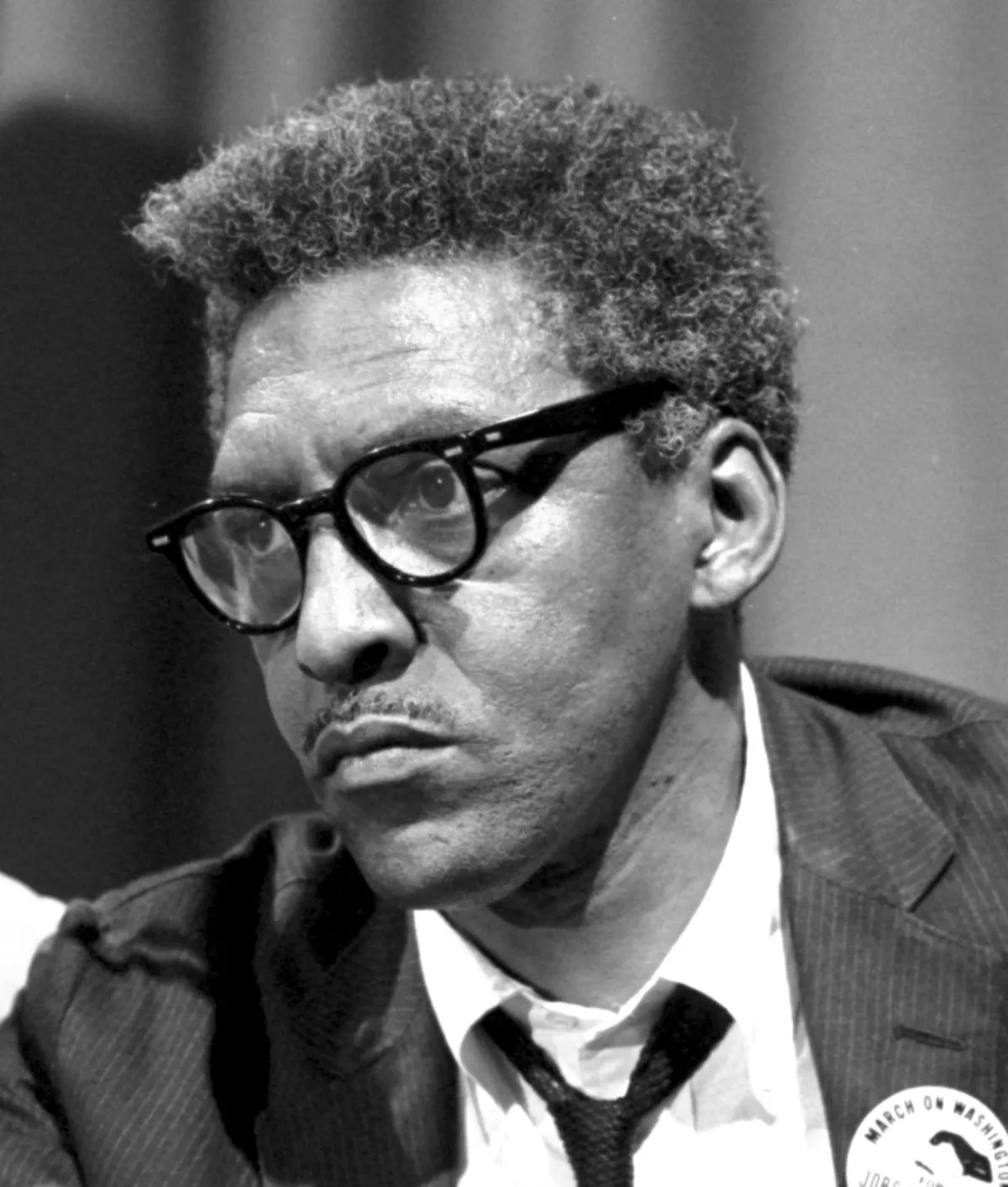

1. Bayard Rustin was an American political activist and prominent leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

1.

1. Bayard Rustin was an American political activist and prominent leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

Bayard Rustin later organized Freedom Rides, and helped to organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to strengthen Martin Luther King Jr.

Bayard Rustin worked alongside Ella Baker, a co-director of the Crusade for Citizenship, in 1954; and before the Montgomery bus boycott, he helped organize a group called "In Friendship" to provide material and legal assistance to people threatened with eviction from their tenant farms and homes.

Later in life, while still devoted to securing workers' rights, Bayard Rustin joined other union leaders in aligning with ideological neoconservatism, earning posthumous praise from President Ronald Reagan.

Bayard Rustin's grandparents were relatively wealthy local caterers who raised Rustin in a large house.

Julia Bayard Rustin was a Quaker, although she attended her husband's African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Bayard Rustin was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Bayard Rustin responded, "I suppose that's what you need to do".

In 1932, Bayard Rustin entered Wilberforce College, a historically black college in Ohio operated by the AME Church.

Bayard Rustin was active in a number of campus organizations, including the Omega Psi Phi fraternity.

Bayard Rustin was expelled from Wilberforce in 1936 after organizing a strike, and later attended Cheyney State Teachers College.

Bayard Rustin joined the Young Communist League in 1936, and left in 1941 after the Communist Party USA reversed its anti-war policy in response to Nazi Germany's invasion of the USSR.

Bayard Rustin was an accomplished tenor vocalist, an asset that earned him admission to both Wilberforce University and Cheyney State Teachers College with music scholarships.

Blues singer Josh White was a cast member and later invited Bayard Rustin to join his gospel and vocal harmony group Josh White and the Carolinians, with whom he made several recordings.

Bayard Rustin considered Rustin to be a fine young man of oratorical ability and intelligence who would sacrifice himself repeatedly for a good cause.

Bayard Rustin had an "infinite capacity for compassion," according to Daniel Levinson.

In 1944, while imprisoned in North Carolina, Bayard Rustin displayed nonviolent tactics.

Bayard Rustin would allow himself to get beaten repeatedly by a white inmate until he gave up, as Rustin was unnerved.

Bayard Rustin defied segregation during that time and practiced his tactic while incarcerated.

Again, Bayard Rustin disagreed with him and voiced his differing opinion in a national press conference, which he later said he regretted.

Bayard Rustin traveled to California to help protect the property of the more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans who had been imprisoned in internment camps.

Bayard Rustin was a pioneer in the movement to desegregate interstate bus travel.

Bayard Rustin was beaten and taken to a police station but was released uncharged.

Bayard Rustin spoke about his decision to be arrested, and how that moment clarified his witness as a gay person, in an interview with the Washington Blade in the 1980s:.

In 1942, Bayard Rustin assisted two other FOR staffers, George Houser and James Farmer, and activist Bernice Fisher as they formed the Congress of Racial Equality.

Bayard Rustin was not a direct founder, but was later described as "an uncle of CORE".

From 1944 to 1946, Bayard Rustin was imprisoned in Ashland Federal Prison in Kentucky, and later the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary, in Pennsylvania.

Just before a trip to Africa while college secretary of the FOR, Bayard Rustin recorded a 10-inch LP, Elizabethan Songs and Negro Spirituals, for the Fellowship Records label.

Bayard Rustin sang spirituals and Elizabethan songs, accompanied on the harpsichord by Margaret Davison.

In 1948, Bayard Rustin traveled to India to learn techniques of nonviolent civil resistance directly from the leaders of the Gandhian movement.

Between 1947 and 1952, Bayard Rustin met with leaders of independence movements in Ghana and Nigeria.

The Pasadena arrest was the first time that Bayard Rustin's homosexuality had come to public attention.

Bayard Rustin resigned from the Fellowship of Reconciliation because of his convictions.

Bayard Rustin became the executive secretary of the War Resisters League.

Bayard Rustin served as an unidentified member of the American Friends Service Committee's task force to write "Speak Truth to Power: A Quaker Search for an Alternative to Violence", published in 1955.

Bayard Rustin took leave from the War Resisters League in 1956 to advise minister Martin Luther King Jr.

Bayard Rustin did not let this setback change his direction in the movement.

Thurmond produced a Federal Bureau of Investigation photograph of Bayard Rustin talking to King while King was bathing, to imply that there was a same-sex relationship between the two.

Bayard Rustin drilled off-duty police officers as marshals, bus captains to direct traffic, and scheduled the podium speakers.

At the beginning of 1964, Reverend Milton Galamison and other Harlem community leaders invited Bayard Rustin to coordinate a citywide boycott of public schools to protest their de facto segregation.

Bayard Rustin said that "the movement to integrate the schools will create far-reaching benefits" for teachers as well as students.

When Bayard Rustin was invited to speak at the University of Virginia in 1964, school administrators tried to ban him, out of fear that he would organize a school boycott there.

Bayard Rustin opposed the hire because of what he considered Rustin's growing devotion to the political theorist Max Shachtman.

At the 1964 Democratic National Convention, which followed Freedom Summer in Mississippi, Bayard Rustin became an adviser to the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party ; they were trying to gain recognition as the legitimate, non-Jim Crow delegation from their state, where blacks had been officially disenfranchised since the turn of the century and excluded from the official political system.

Bayard Rustin wrote presciently that the rise of automation would reduce the demand for low-skill high-paying jobs, which would jeopardize the position of the urban African-American working class, particularly in northern states.

Bayard Rustin believed that the working class had to collaborate across racial lines for common economic goals.

Bayard Rustin's prophecy has been proven right in the dislocation and loss of jobs for many urban African Americans due to the restructuring of industry in the coming decades.

Bayard Rustin wrote that it was time to move from protest to politics.

Bayard Rustin argued that since black people could now legally sit in the restaurant after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, they needed to be able to afford service financially.

Bayard Rustin believed that a coalition of progressive forces to move the Democratic Party forward was needed to change the economic structure.

Bayard Rustin argued that the African-American community was threatened by the appeal of identity politics, particularly the rise of "Black power".

Bayard Rustin thought this position was a fantasy of middle-class black people that repeated the political and moral errors of previous black nationalists, while alienating the white allies needed by the African-American community.

In 1985, Bayard Rustin publicly praised Podhoretz for his refusal to "pander to minority groups" and for opposing affirmative action quotas in hiring as well as black studies programs in colleges.

Bayard Rustin was making radical and ambitious demands for a basic redistribution of wealth in American society, including universal healthcare, the abolition of poverty, and full employment.

Bayard Rustin increasingly worked to strengthen the labor movement, which he saw as the champion of empowerment for the African American community and for economic justice for all Americans.

Bayard Rustin contributed to the labor movement's two sides, economic and political, through the support of labor unions and social-democratic politics.

Bayard Rustin was the founder and became the Director of the A Philip Randolph Institute, which coordinated the AFL-CIO's work on civil rights and economic justice.

Bayard Rustin became a regular columnist for the AFL-CIO newspaper.

In later years, Bayard Rustin served as the national chairman of SDUSA.

Bayard Rustin would remain a member for years, and became vice president during the 1980s.

Bayard Rustin maintained his strongly anti-Soviet and anti-communist views later in his life, especially with regard to Africa.

In 1976, Bayard Rustin was a member of the anti-communist Committee on the Present Danger, founded by politician Paul Nitze.

Bayard Rustin worked closely with Senator Henry Jackson of Washington, who introduced legislation that tied trade relations with the Soviet Union to their treatment of Jews.

Bayard Rustin co-sponsored the National Interreligious Task Force on Soviet Jewry.

Bayard Rustin was at the forefront of the freedom struggle for African Americans but parted ways from the activists in 1968.

Bayard Rustin wanted blacks to align themselves with whites to see progression.

Bayard Rustin's relationships were mainly with the men, both black and white.

Bayard Rustin's awareness left no worry, and his family openly accepted it.

Bayard Rustin did not engage in any gay rights activism until the 1980s.

We actually had to go through a process as if Bayard Rustin was adopting a small child.

Bayard Rustin testified in favor of the New York City Gay Rights Bill.

Also in 1986, Bayard Rustin was invited to contribute to the book In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology.

Bayard Rustin died on August 24,1987, of a perforated appendix.

President Ronald Reagan issued a statement on Bayard Rustin's death, praising his work for civil rights and "for human rights throughout the world".

Bayard Rustin added that Rustin "was denounced by former friends, because he never gave up his conviction that minorities in America could and would succeed based on their individual merit".

Bayard Rustin served as chairman of Social Democrats, USA, which, The Washington Post wrote in 2013, "was a breeding ground for many neoconservatives".

Bayard Rustin is one of two men who have both participated in the Penn Relays and had a school, West Chester Bayard Rustin High School, named in his honor that participates in the relays.

Formerly the Queer and Allied Resource Center, the center was rededicated in March 2011 with the permission of the Estate of Bayard Rustin and featured a keynote address by social justice activist Mandy Carter.

In 2012, Bayard Rustin was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display which celebrates LGBTQ history and people.

In 2013, Bayard Rustin was selected as an honoree in the United States Department of Labor Hall of Honor.

Bayard Rustin was an unyielding activist for civil rights, dignity, and equality for all.

In 2014, Bayard Rustin was one of the inaugural honorees in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a walk of fame in San Francisco's Castro neighborhood noting LGBTQ people who have "made significant contributions in their fields".

Bayard Rustin was one of the fifty inaugural American "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes" inducted in June 2019 to the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor, within the Stonewall National Monument in New York City's Stonewall Inn.

On June 5,2023, the Pasadena City Council adopted a resolution introduced by Councilmember Jason Lyon declaring that the "City of Pasadena celebrates and concurs in the Governor's 2020 pardon of Bayard Rustin" and supporting the issuance of a commemorative United States postage stamp honoring Rustin.