1.

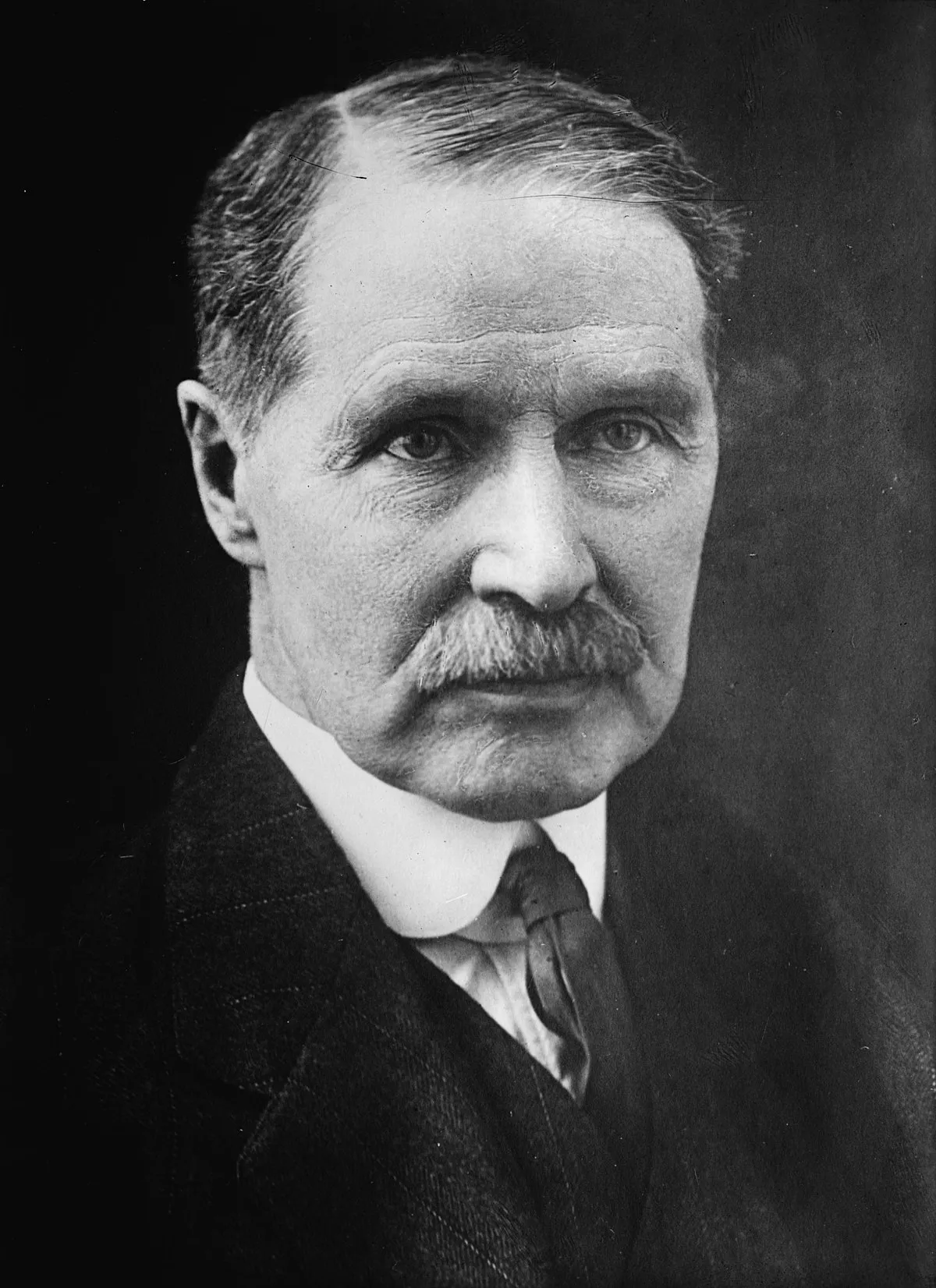

1. Andrew Bonar Law was a British statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

1.

1. Andrew Bonar Law was a British statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Bonar Law was of Scottish and Ulster Scots descent and moved to Scotland in 1870.

Bonar Law left school aged sixteen to work in the iron industry, becoming a wealthy man by the age of thirty.

Bonar Law entered the House of Commons at the 1900 general election, relatively late in life for a front-rank politician; he was made a junior minister, Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade, in 1902.

Bonar Law joined the Shadow Cabinet in opposition after the 1906 general election.

Bonar Law's campaigning helped turn Liberal attempts to pass the Third Home Rule Bill into a three-year struggle eventually halted by the start of World War I, with much argument over the status of the six counties in Ulster which would later become Northern Ireland, four of which were predominantly Protestant.

Bonar Law resigned on grounds of ill health early in 1921.

Bonar Law won a clear majority at the 1922 general election, and his brief premiership saw negotiation with the United States over Britain's war loans.

Seriously ill with throat cancer, Bonar Law resigned in May 1923, and died later that year.

Bonar Law was the fourth shortest-serving prime minister of the United Kingdom.

Andrew Bonar Law was born on 16 September 1858 in Kingston, New Brunswick, to the Reverend James Law, a minister of the Free Church of Scotland, and his wife Eliza Kidston Law.

Bonar Law was referred to as Bonar Law by the public.

James Bonar Law was the minister for several isolated townships, and had to travel between them by horse, boat and on foot.

When James Bonar Law remarried in 1870, his new wife took over Janet's duties, and Janet decided to return home to Scotland.

Bonar Law suggested that Bonar Law should go with her, as the Kidston family were wealthier and better connected than the Laws, and Bonar would have a more privileged upbringing.

Bonar Law went to live at Janet's house in Helensburgh, near Glasgow.

Immediately upon arriving from Kingston, Bonar Law began attending Gilbertfield House School, a preparatory school in Hamilton.

Bonar Law eventually became a very good amateur player, and competed with internationally renowned chess masters.

Bonar Law had time to devote to more leisurely pursuits.

Bonar Law remained an avid chess player, whom Andrew Harley called "a strong player, touching first-class amateur level, which he had attained by practice at the Glasgow Club in earlier days".

Bonar Law worked with the Parliamentary Debating Association, and took up golf, tennis and walking.

In 1890, Bonar Law met Annie Pitcairn Robley, the 24-year-old daughter of a Glaswegian merchant, Harrington Robley.

In 1897, Bonar Law was asked to become the Conservative Party candidate for the parliamentary seat of Glasgow Bridgeton.

The campaign was unpleasant for both sides, with anti- and pro-war campaigners fighting vociferously, but Bonar Law distinguished himself with his oratory and wit.

Bonar Law immediately ended his active work at Jacks and Company and moved to London.

Bonar Law initially became frustrated with the slow speed of Parliament compared to the rapid pace of the Glasgow iron market, and Austen Chamberlain recalled him saying to Chamberlain that "it was very well for men who, like myself had been able to enter the House of Commons young to adapt to a Parliamentary career, but if he had known what the House of Commons was he would never had entered at this stage".

Bonar Law soon learnt to be patient and on 18 February 1901 made his maiden speech.

Bonar Law took advantage of this, making his first major speech on 22 April 1902, in which he argued that while he felt a general tariff was unnecessary, an imperial customs union was a good idea, particularly since other nations such as and the United States had increasingly high tariffs.

Bonar Law was a dedicated Tariff Reformer, but whereas Chamberlain dreamed of a new golden age for Britain, Bonar Law focused on more mundane and practical goals, such as a reduction in unemployment.

Amery said that to Bonar Law, the tariff reform programme was "a question of trade figures and not national and Imperial policy of expansion and consolidation of which trade was merely the economic factor".

Bonar Law was returned to Parliament in the ensuing by-election, increasing the Conservative majority to 1,279.

Bonar Law was succeeded as leader of the tariff reformers by his son Austen Chamberlain, who despite previous experience as Chancellor of the Exchequer and enthusiasm for tariff reform was not as skilled a speaker as Law.

The Liberals called a general election for January 1910, and Bonar Law spent most of the preceding months campaigning up and down the country for other Unionist candidates and MPs, sure that his Dulwich seat was safe.

The Conservatives were led by Arthur Balfour and Lord Lansdowne, who headed the Conservatives in the House of Lords, while Bonar Law spent the time concentrating on the continuing problem of tariff reform.

Bonar Law disagreed, successfully arguing that tariff reform "was the first constructive work of the [Conservative Party]" and that to scrap it would "split the Party from top to bottom".

Bonar Law was selected as the candidate for Manchester North West, and became drawn into party debates about how strong a tariff reform policy should be put in their manifesto.

Bonar Law personally felt that duties on foodstuffs should be excluded, something agreed to by Alexander Acland-Hood, Edward Carson and others at a meeting of the Constitutional Club on 8 November 1910, but they failed to reach a consensus and the idea of including or excluding food duties continued to be something that divided the party.

Bonar Law called his campaign in Manchester North West the hardest of his career; his opponent, George Kemp, was a war hero who had fought in the Second Boer War and a former Conservative who had joined the Liberal party because of his disagreement with tariff reform.

In 1911, with the Conservative Party unable to afford him being out of Parliament, Bonar Law was elected in a March 1911 by-election for the safe Conservative seat of Bootle.

Bonar Law favoured surrender on pragmatic grounds, as a Unionist-dominated House of Lords would retain some ability to delay Liberal attempts to introduce Irish Home Rule, Welsh Disestablishment or electoral reforms gerrymandered to help the Liberal Party.

Bonar Law himself had no problem with Balfour's leadership, and along with Edward Carson attempted to regain support for him.

At the beginning of the election Bonar Law held the support of no more than 40 of the 270 members of parliament; the remaining 230 were divided between Long and Chamberlain.

Bonar Law's biographer, Robert Blake, wrote that he was an unusual choice to lead the Conservatives as a Presbyterian Canadian-Scots businessman had just become the leader of "the Party of Old England, the Party of the Anglican Church and the country squire, the party of broad acres and hereditary titles".

In Parliament, Bonar Law introduced the so-called "new style" of speaking, with harsh, accusatory rhetoric, which dominates British politics to this day.

In terms of social reform Bonar Law was similarly unenthusiastic, believing that the area was a Liberal one, in which they could not successfully compete.

Bonar Law endorsed Lansdowne's argument, pointing out that any attempt to avoid food duties would cause an internal party struggle and could only aid the Liberals, and that Canada, the most economically important colony and a major exporter of foodstuffs, would never agree to tariffs without British support of food duties.

Bonar Law replied arguing that it would be impossible to do so effectively, and that with the increasing costs of defence and social programmes it would be impossible to raise the necessary capital except by comprehensive tariff reform.

Bonar Law argued that a failure to offer the entire tariff reform package would split the Conservative Party down the middle, offending the tariff reform faction, and that if such a split took place "I could not possibly continue as leader".

Bonar Law postponed withdrawing the tariff reform "Referendum Pledge" because of the visit of Robert Borden, the newly elected Conservative prime minister of Canada, to London planned for July 1912.

Bonar Law refused to condemn the events, and it seems apparent that while he had played no part in organising them, they had been planned by the party whips.

Bonar Law then rose to speak, and in line with his agreement to let Lansdowne speak for tariff reform mentioned it only briefly when he said "I concur in every word which has fallen from Lord Lansdowne".

Bonar Law instead promised a reversal of several Liberal policies when the Unionists came to power, including the disestablishment of the Welsh Church, land taxes, and Irish Home Rule.

Bonar Law was preoccupied with the problem of Irish Home Rule and was unable to give the discontent his full attention.

Bonar Law again wrote to Strachey saying that he continued to feel this policy was the correct one, and only regretted that the issue was splitting the party at a time when unity was needed to fight the Home Rule problem.

In contrast to Balfour's "milk and water" opposition to Home Rule, Bonar Law presented a "fire and blood" opposition to Home Rule that at times seemed to suggest that he was willing to contemplate a civil war to stop Home Rule.

Right form the start, Bonar Law presented his anti-Home Rule stance more in terms of protecting Protestant majority Ulster from being ruled by a Parliament in Dublin that would be dominated by Catholics than in terms of preserving the Union, much to the chagrin of many Unionists.

Bonar Law was supported by Sir Edward Carson, leader of the Ulster Unionists.

Besides for his concerns about the violence, Dicey was worried about the way in which Bonar Law was more interested about stopping Home Rule from being imposed on Ulster, instead of all of Ireland, which seemed to imply he was willing to accept the partition of Ireland.

Many Irish Unionists outside of Ulster felt abandoned by Bonar Law, who seemed to care only about Ulster.

Bonar Law warned that "you will not carry this Bill without submitting it to the people of this country, and, if you make the attempt, you will succeed only in breaking our Parliamentary machine".

Bonar Law added that if Asquith continued with the Home Rule bill, the government would be "lighting the fires of civil war".

Bonar Law saw this as a victory, as it highlighted the split in the government.

The Conservative politician Lord Hythe, wrote to Bonar Law to suggest the Conservatives needed to present a constructive alternative to Home Rule and he had the "duty to tell these Ulstermen" that there was no need for the UVF.

Lord Lansdowne advised Law to be "extremely careful in our relations with Carson and his friends" and find a way of stopping F E Smith's "habit of expressing rather violent sentiments in the guise of messages from the Unionist party".

However, Carson's amendment which would lead to the partition of Ireland caused much alarm with Irish Unionists outside of Ulster and led many to write letters from Bonar Law seeking assurances that he would not abandon them for the sake of saving Ulster from Home Rule.

Fending this off, Bonar Law instead met with senior party members to discuss developments.

Bonar Law then met with Edward Carson, and afterwards expressed the opinion that "the men of Ulster do desire a settlement on the basis of leaving Ulster out, and Carson thinks such an arrangement could be carried out without any serious attack from the Unionists in the South".

The meeting lasted an hour, and Bonar Law told Asquith that he would continue to try to have Parliament dissolved, and that in any ensuing election the Unionists would accept the result even if it went against them.

Bonar Law knew that Asquith was unlikely to consent to a general election, since he would almost certainly lose it, and that any attempt to pass the Home Rule Bill "without reference to the electorate" would lead to civil disturbance.

Bonar Law made it clear to Asquith that the first two options were unacceptable, but the third might be accepted in some circles.

Carson always referred to nine counties of Ulster, but Bonar Law told Asquith that if an appropriate settlement could be made with a smaller number, Carson "would see his people and probably, though I could not give any promise to that effect, try to induce them to accept it".

Bonar Law brushed aside Asquith's suggestions and insisted that only the exclusion of Ulster was worth considering.

Bonar Law's critics, including George Dangerfield, condemned his actions in assuring the Ulster Unionists of Conservative Party support in their armed resistance to Home Rule, as unconstitutional, verging on promoting a civil war.

Bonar Law's supporters argued that he was acting constitutionally by forcing the Liberal government into calling the election it had been avoiding, to obtain a mandate for their reforms.

Bonar Law was not directly involved in the British Covenant campaign as he was focusing on a practical way to defeat the Home Rule Bill.

Bonar Law believed that subjecting Ulstermen to a Dublin-based government they did not recognise was itself constitutionally damaging, and that amending the Army Act to prevent the use of force in Ulster would not violate the constitution any more than the actions the government had already undertaken.

On 30 July 1914, on the eve of World War I, Bonar Law met with Asquith and agreed to temporarily suspend the issue of Home Rule to avoid domestic discontent during wartime.

Bonar Law was supportive of the idea in some ways, seeing it as a probability that "a coalition government would come in time".

Bonar Law eventually accepted the post of Colonial Secretary, an unimportant post in wartime; Asquith had made it clear that he would not allow a Conservative minister to head the Exchequer, and that with Kitchener in the War Office, he would not allow another Conservative to hold a similarly important position.

Bonar Law entered the coalition government as Colonial Secretary in May 1915, his first Cabinet post, and, following the resignation of Prime Minister and Liberal Party Leader Asquith in December 1916, was invited by King George V to form a government, but he deferred to Lloyd George, Secretary of State for War and former Minister of Munitions, who he believed was better placed to lead a coalition ministry.

Bonar Law served in Lloyd George's War Cabinet, first as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons.

Bonar Law's promotion reflected the great mutual trust between the two leaders and made for a well co-ordinated political partnership; their coalition was re-elected by a landslide following the Armistice.

At war's end, Bonar Law gave up the Exchequer for the less demanding sinecure office of Lord Privy Seal, but remained Leader of the Commons.

Bonar Law's departure weakened the hardliners in the cabinet who were opposed to negotiating with the Irish Republican Army, and the Anglo-Irish War ended in the summer.

Lloyd George, Birkenhead and Winston Churchill wished to use armed force against Turkey, but had to back down when offered support only by New Zealand and Newfoundland, and not Canada, Australia or the Union of South Africa; Bonar Law wrote to The Times in support of the government, but stating that Britain could not "act as the policeman for the world".

Austen Chamberlain resigned as Party Leader, Lloyd George resigned as prime minister and Bonar Law took both jobs on 23 October 1922.

Bonar Law found Farquhar too "gaga" to properly explain what had happened, and dismissed him.

Bonar Law contemplated resignation, and after being talked out of it by senior ministers vented his feelings in an anonymous letter to The Times.

Bonar Law was diagnosed with terminal throat cancer and, no longer physically able to speak in Parliament, resigned on 20 May 1923.

King George V sent for Baldwin, whom Bonar Law is rumoured to have favoured over Lord Curzon.

Bonar Law died later that same year in London at the age of 65.

Bonar Law's funeral was held at Westminster Abbey where later his ashes were interred.

Bonar Law was the first British prime minister to be cremated.

Bonar Law was the shortest-serving prime minister of the 20th century.

Bonar Law is often referred to as "the unknown prime minister", not least because of a biography of that title by Robert Blake; the name comes from a remark by Asquith at Law's funeral, that they were burying the Unknown Prime Minister next to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

Additionally, the Bonar Law-Bennett Building, a former University of New Brunswick campus library which now houses the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, was named after both Law and R B Bennett.