1.

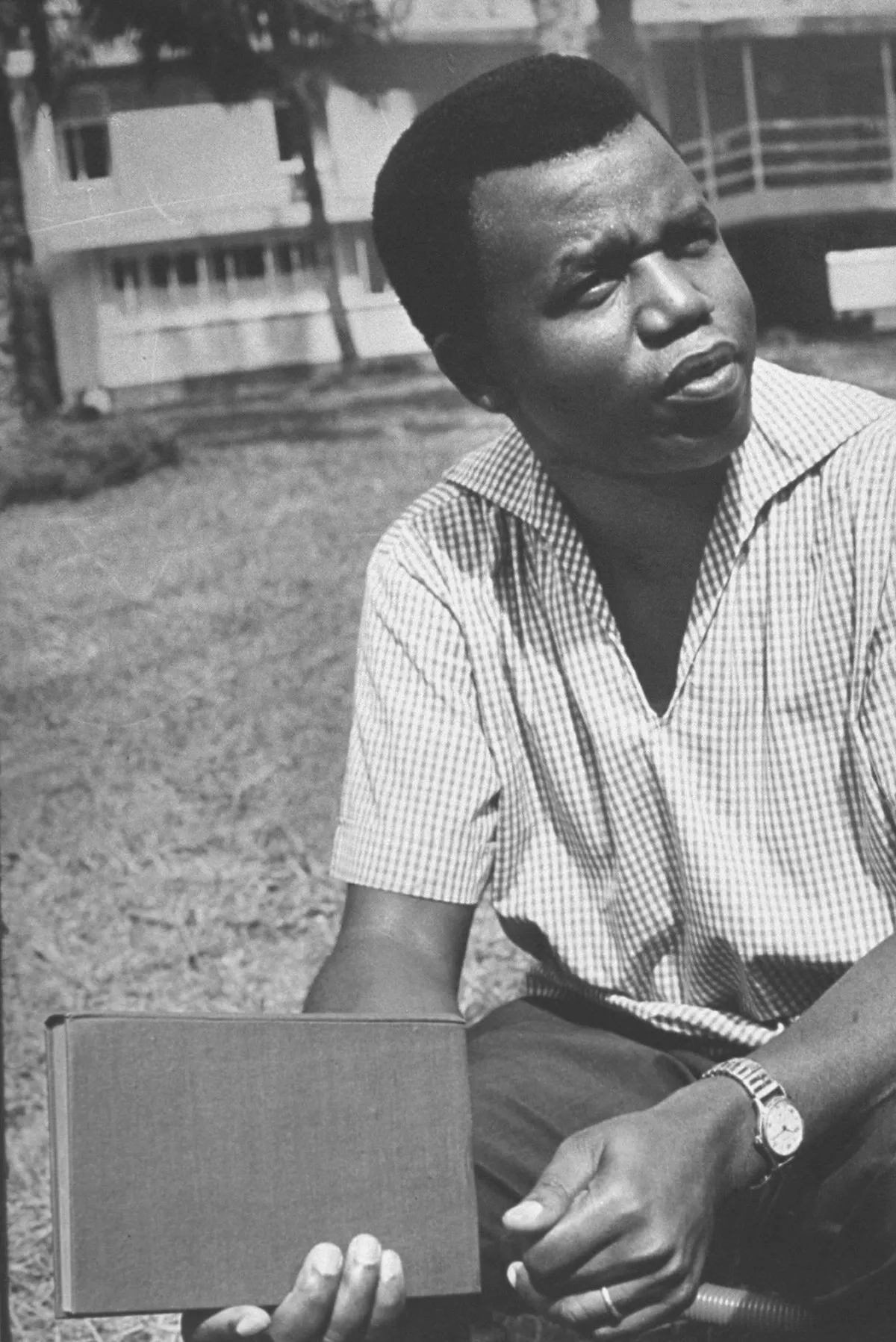

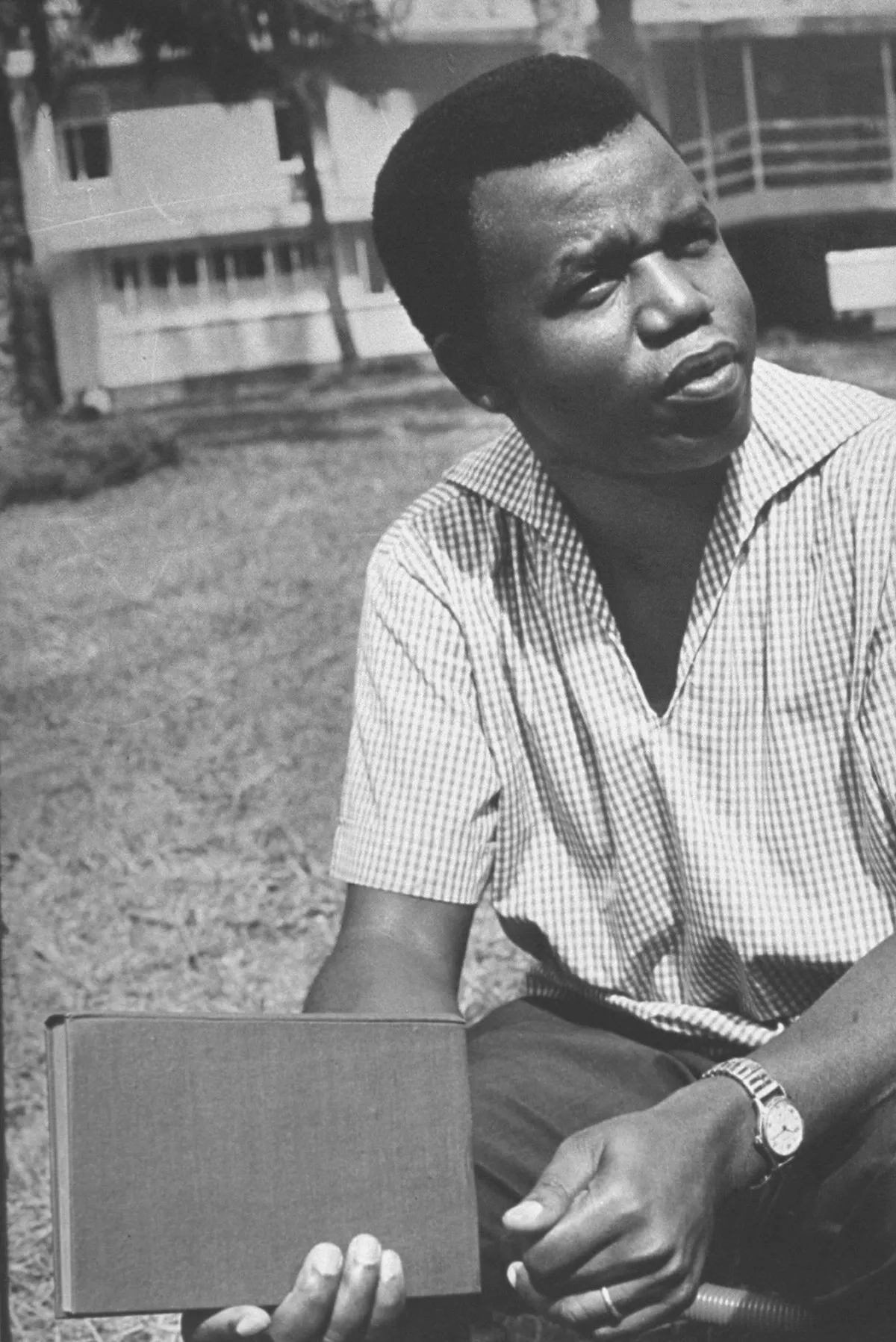

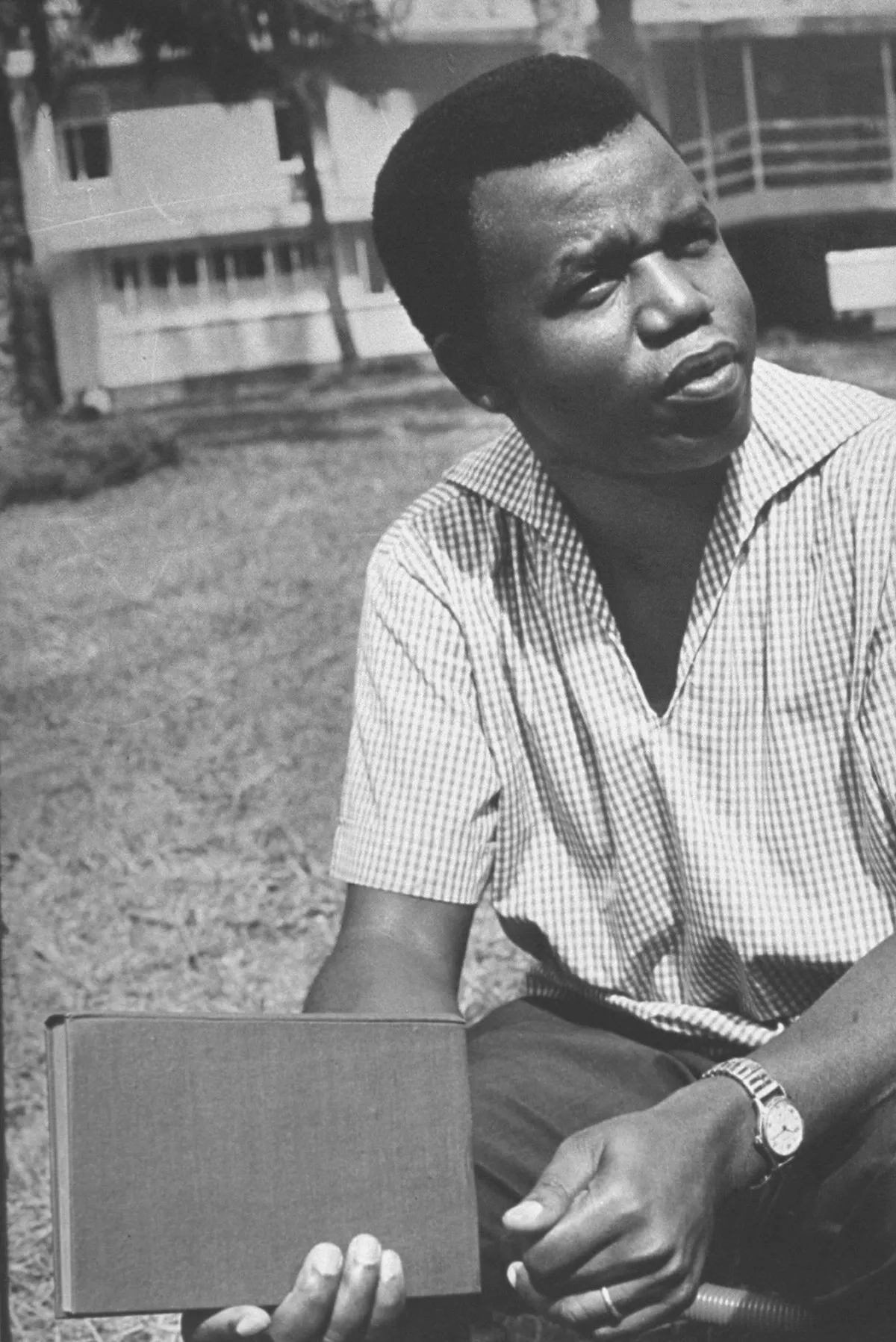

1. Chinua Achebe was a Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic who is regarded as a central figure of modern African literature.

1.

1. Chinua Achebe was a Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic who is regarded as a central figure of modern African literature.

Chinua Achebe excelled in school and attended what is the University of Ibadan, where he became fiercely critical of how Western literature depicted Africa.

Chinua Achebe sought to escape the colonial perspective that framed African literature at the time, and drew from the traditions of the Igbo people, Christian influences, and the clash of Western and African values to create a uniquely African voice.

Chinua Achebe wrote in and defended the use of English, describing it as a means to reach a broad audience, particularly readers of colonial nations.

Chinua Achebe lived in the United States for several years in the 1970s, and returned to the US in 1990 after a car crash left him partially paralyzed.

Chinua Achebe stayed in the US in a nineteen-year tenure at Bard College as a professor of languages and literature.

Chinua Achebe's work has been extensively analyzed and a vast body of scholarly work discussing it has arisen.

Chinua Achebe's legacy is celebrated annually at the Chinua Achebe Literary Festival.

Chinua Achebe was born on 16 November 1930 and baptised Albert Chinualumogu Achebe.

Chinua Achebe's father, Isaiah Okafo Achebe, was a teacher and evangelist, and his mother, Janet Anaenechi Iloegbunam, was the daughter of a blacksmith from Awka, a leader among church women, and a vegetable farmer.

Chinua Achebe's birthplace was Saint Simon's Church, Nneobi, which was near the Igbo village of Ogidi; the area was part of the British colony of Nigeria at the time.

Chinua Achebe's parents were converts to the Protestant Church Mission Society in Nigeria.

Chinua Achebe eagerly anticipated traditional village events, like the constant masquerade ceremonies, which he would later recreate in his novels and stories.

In 1936, Chinua Achebe entered St Philips' Central School in the Akpakaogwe region of Ogidi for his primary education.

Chinua Achebe had his secondary education at the prestigious Government College Umuahia, in Nigeria's present-day Abia State.

Chinua Achebe attended Sunday school every week and the special services held monthly, often carrying his father's bag.

Chinua Achebe enrolled in Nekede Central School, outside of Owerri, in 1942; he was particularly studious and passed the entrance examinations for two colleges.

Chinua Achebe was admitted as the university's first intake and given a bursary to study medicine.

Chinua Achebe decided to become a writer after reading Mister Johnson by Joyce Cary because of the book's portrayal of its Nigerian characters as either savages or buffoons.

Chinua Achebe recognised his dislike for the African protagonist as a sign of the author's cultural ignorance.

Chinua Achebe abandoned medicine to study English, history, and theology, a switch which lost him his scholarship and required extra tuition fees.

Chinua Achebe followed with other essays and letters about philosophy and freedom in academia, some of which were published in another campus magazine called The Bug.

Chinua Achebe wrote his first short story that year, "In a Village Church", an amusing look at the Igbo synthesis between life in rural Nigeria with Christian institutions and icons.

The students did not have access to the newspapers he had read as a student, so Chinua Achebe made his own available in the classroom.

Chinua Achebe left the institution in 1954 and moved to Lagos to work for the Nigerian Broadcasting Service, a radio network started in 1933 by the colonial government.

Chinua Achebe was assigned to the Talks Department to prepare scripts for oral delivery.

Chinua Achebe revelled in the social and political activity around him and began work on a novel.

Also in 1956, Chinua Achebe was selected to attend the staff training school for the BBC.

Chinua Achebe's first trip outside Nigeria was an opportunity to advance his technical production skills, and to solicit feedback on his novel.

Back in Nigeria, Achebe set to work revising and editing his novel; he titled it Things Fall Apart, after a line in the poem "The Second Coming" by W B Yeats.

Chinua Achebe cut away the second and third sections of the book, leaving only the story of a yam farmer named Okonkwo who lives during the colonization of Nigeria and struggles with his father's debtor legacy.

Chinua Achebe added sections, improved various chapters, and restructured the prose.

Chinua Achebe did not receive a reply from the typing service, so he asked his boss at the NBS, Angela Beattie, to visit the company during her travels to London.

Chinua Achebe did, and angrily demanded to know why the manuscript was lying ignored in the corner of the office.

The Observer called it "an excellent novel", and the literary magazine Time and Tide said that "Mr Chinua Achebe's style is a model for aspirants".

That same year Chinua Achebe began dating Christiana Chinwe Okoli, a woman who had grown up in the area and joined the NBS staff when he arrived.

In 1960 Chinua Achebe published No Longer at Ease, a novel about a civil servant named Obi, grandson of Things Fall Aparts main character, who is embroiled in the corruption of Lagos.

Later that year, Chinua Achebe was awarded a Rockefeller Fellowship for six months of travel, which he called "the first important perk of my writing career".

Chinua Achebe first travelled to Kenya, where he was required to complete an immigration form by checking a box indicating his ethnicity: European, Asiatic, Arab, or Other.

Chinua Achebe found in his travels that Swahili was gaining prominence as a major African language.

Chinua Achebe met the poet Sheikh Shaaban Robert, who complained of the difficulty he had faced in trying to publish his Swahili-language work.

In Northern Rhodesia, Chinua Achebe found himself sitting in a whites-only section of a bus to Victoria Falls.

Two years later, Chinua Achebe travelled to the United States and Brazil as part of a Fellowship for Creative Artists awarded by UNESCO.

Chinua Achebe met with a number of writers from the US, including novelists Ralph Ellison and Arthur Miller.

On his return to Nigeria in 1961, Chinua Achebe was promoted at the NBS to the position of Director of External Broadcasting.

Chinua Achebe became particularly saddened by the evidence of corruption and silencing of political opposition.

Chinua Achebe met with literary figures including Ghanaian poet Kofi Awoonor, Nigerian playwright and novelist Wole Soyinka, and American poet Langston Hughes.

Chinua Achebe indicated that it was not "a very significant question", and that scholars would do well to wait until a body of work was large enough to judge.

Chinua Achebe became the General Editor of the African Writers Series, a collection of postcolonial literature from African writers.

Chinua Achebe published an essay entitled "Where Angels Fear to Tread" in the December 1962 issue of Nigeria Magazine in reaction to critiques African work was receiving from international authors.

In 1966, Chinua Achebe published his first children's book, Chike and the River, to address some of these concerns.

The idea for the novel came in 1959, when Chinua Achebe heard the story of a Chief Priest being imprisoned by a District Officer.

Chinua Achebe drew further inspiration a year later when he viewed a collection of Igbo objects excavated from the area by archaeologist Thurstan Shaw; Achebe was startled by the cultural sophistication of the artefacts.

Chinua Achebe responded by suggesting that the individualistic hero was rare in African literature, given its roots in communal living and the degree to which characters are "subject to non-human forces in the universe".

One of its first submissions was a story called How the Dog was Domesticated, which Chinua Achebe revised and rewrote, turning it into a complex allegory for the country's political tumult.

Chinua Achebe was shaken considerably by the loss; in 1971 he wrote "Dirge for Okigbo", originally in the Igbo language but later translated to English.

Chinua Achebe continued to write throughout the war, but most of his creative work during this time took the form of poetry.

In September 1968, the city of Aba fell to the Nigerian military and Chinua Achebe moved his family, this time to Umuahia, where the Biafran government had relocated.

Chinua Achebe was chosen to chair the newly formed National Guidance Committee, charged with the task of drafting principles and ideas for the post-war era.

Chinua Achebe took a job at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka and immersed himself in academia.

Chinua Achebe was unable to accept invitations to other countries because the Nigerian government revoked his passport due to his support for Biafra.

The Chinua Achebe family had another daughter on 7 March 1970, named Nwando.

Chinua Achebe handed over the editorship of Okike to Onuora Osmond Enekwe, who was later assisted by Amechi Akwanya.

In February 1972, Chinua Achebe released Girls at War, a collection of short stories ranging in time from his undergraduate days to the recent bloodshed.

Chinua Achebe helped her face what he called the "alien experience" by telling her stories during the car trips to and from school.

Chinua Achebe expanded this criticism when he presented a Chancellor's Lecture at Amherst on 18 February 1975, "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness".

Chinua Achebe's criticism has become a mainstream perspective on Conrad's work.

Chinua Achebe published a book called The Trouble with Nigeria to coincide with the upcoming elections.

Chinua Achebe left the PRP and kept his distance from political parties, expressing sadness with his perception of the dishonesty and weakness of the people involved.

Chinua Achebe spent most of the 1980s delivering speeches, attending conferences, and working on his sixth novel.

In 1987 Chinua Achebe released his fifth novel, Anthills of the Savannah, about a military coup in the fictional West African nation of Kangan.

On 22 March 1990, Chinua Achebe was riding in a car to Lagos when an axle collapsed and the car flipped.

Chinua Achebe was flown to the Paddocks Hospital in Buckinghamshire, England, and treated for his injuries.

In 2000 Chinua Achebe published Home and Exile, a semi-biographical collection of both his thoughts on life away from Nigeria, as well as discussion of the emerging school of Native American literature.

In October 2005, the London Financial Times reported that Chinua Achebe was planning to write a novella for the Canongate Myth Series, a series of short novels in which ancient myths from myriad cultures are reimagined and rewritten by contemporary authors.

Chinua Achebe was awarded the Man Booker International Prize in June 2007.

In 2010, Chinua Achebe was awarded The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize for $300,000, one of the richest prizes for the arts.

In 2012, Chinua Achebe published There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra.

Chinua Achebe used proverbs to describe the values of the rural Igbo tradition.

Chinua Achebe includes them throughout the narratives, repeating points made in conversation.

Chinua Achebe's work is scrutinised for its subject matter, insistence on a non-colonial narrative, and use of English.

Chinua Achebe recognises the shortcomings of what Audre Lorde called "the master's tools".

Chinua Achebe often finds himself describing situations or modes of thought which have no direct equivalent in the English way of life.

Chinua Achebe's novels were a foundation for this process; by altering syntax, usage, and idiom, he transformed the language into a distinctly African style.

At a time when African writers were being admonished for being obsessed with the past, Chinua Achebe argued that confronted by colonial denigration, evacuated from the category of the human, and denied the capacity for thinking and creativity, the African needed a narrative of redemption.

Chinua Achebe later embodied this tension between African tradition and Western influence in the figure of Sam Okoli, the president of Kangan in Anthills of the Savannah.

The colonial impact on the Igbo in Chinua Achebe's novels is often affected by individuals from Europe, but institutions and urban offices frequently serve a similar purpose.

Chinua Achebe seeks to portray neither moral absolutes nor a fatalistic inevitability.

The African studies scholar Rose Ure Mezu suggests that Chinua Achebe is representing the limited gendered vision of the characters, or that he purposefully created exaggerated gender binaries to render Igbo history recognizable to international readers.

Conversely, the scholar Ajoke Mimiko Bestman has stated that reading Chinua Achebe through the lens of womanism is "an afrocentric concept forged out of global feminism to analyze the condition of Black African women" which acknowledges the patriarchal oppression of women and highlights the resistance and dignity of African women, which enables an understanding of Igbo conceptions of gender complementarity.

Chinua Achebe's obsession with maleness is fueled by an intense fear of femaleness, which he expresses through the physical and verbal abuse of his wives, his violence towards his community, his constant worry that his son Nwoye is not manly enough, and his wish that his daughter Ezinma had been born a boy.

Chinua Achebe rejected such descriptions as patronising and eurocentric, which were qualities his work sought to critique in the first place.

Chinua Achebe countered white descriptions of himself as such by claiming that "education is lacking in most of those who pontificate".

Nobel laureate Toni Morrison noted that Chinua Achebe's work inspired her to become a writer and "sparked her love affair with African literature".

Chinua Achebe received over 30 honorary degrees from universities in Nigeria, Canada, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States, including Dartmouth College, Harvard, and Brown.

Chinua Achebe was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador by the United Nations Population Fund in 1999.

Chinua Achebe was created the "Ugonabo" of Ogidi, a Nigerian chieftain, by the people of his ancestral hometown in 2013.

Chinua Achebe himself had attended the film's premiere in Atlanta in 1974.

Chinua Achebe was honoured as Grand Prix de la Memoire of the 2019 edition of the Grand Prix of Literary Associations prize.