1.

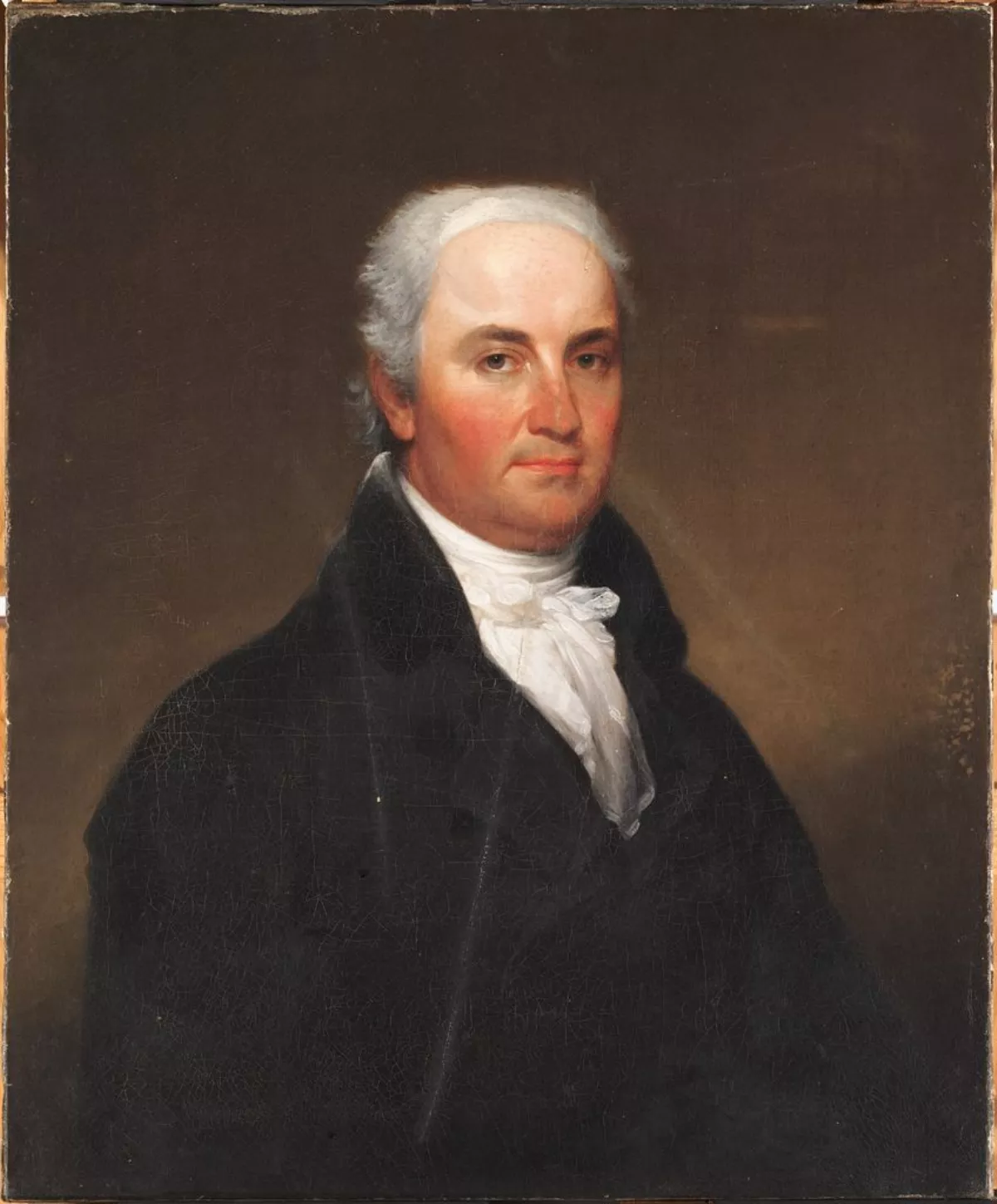

1. Christopher Gore was a prominent Massachusetts lawyer, Federalist politician, and US diplomat.

1.

1. Christopher Gore was a prominent Massachusetts lawyer, Federalist politician, and US diplomat.

Christopher Gore entered politics in 1788, serving briefly in the Massachusetts legislature before being appointed US District Attorney for Massachusetts.

Christopher Gore was then appointed by President George Washington to a diplomatic commission dealing with maritime claims in Great Britain.

Christopher Gore returned to Massachusetts in 1804 and reentered state politics, running unsuccessfully for governor several times before winning in 1809.

Christopher Gore served one term, losing to Democratic-Republican Elbridge Gerry in 1810.

Christopher Gore was appointed to the US Senate by Governor Caleb Strong in 1813, where he led opposition to the War of 1812.

Christopher Gore invested his fortune in a variety of businesses, including important infrastructure projects such as the Middlesex Canal and a bridge across the Charles River.

Christopher Gore was a major investor in the early textile industry, funding the Boston Manufacturing Company and the Merrimack Manufacturing Company, whose business established the city of Lowell, Massachusetts.

Christopher Gore was involved in a variety of charitable causes, and was a major benefactor of Harvard College, where the first library was named in his honor.

Christopher Gore was the youngest of their three sons to survive to adulthood.

Christopher Gore attended Boston Latin School, and entered Harvard College at the young age of thirteen.

At the outset of the American Revolutionary War and the siege of Boston in 1775, Harvard's buildings were occupied by the Continental Army, and Christopher Gore temporarily continued his studies in Bradford until Harvard could resume operations in Concord.

Christopher Gore graduated in 1776, and promptly enlisted in the Continental artillery regiment of his brother-in-law Thomas Crafts, where he served as a clerk until 1778.

Christopher Gore was consequently called upon to support his mother and three sisters, who remained in Boston.

In 1779, Christopher Gore successfully petitioned the state for the remaining family's share of his father's seized assets.

Christopher Gore's clients included Loyalists seeking to recover some of their assets, as well as London-based British merchants with claims to pursue.

Christopher Gore's briefs were generally well-reasoned, and he was seen as a successful trial lawyer.

Christopher Gore grew his fortune by investing carefully in revolutionary currency and bonds.

In 1786 Christopher Gore became concerned about a rise in anti-lawyer sentiment in Massachusetts.

In 1788, Christopher Gore was elected a delegate to the 1789 Massachusetts convention that ratified the United States Constitution.

Christopher Gore's election was contested because Boston, where he lived, was at the time more inclined toward state power.

Christopher Gore nonetheless was strongly Federalist, urging support of the new Constitution.

In 1788 Christopher Gore was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives.

Christopher Gore took a leading role in adopting the state's rules for actions required of it by the new federal constitution.

Christopher Gore proposed that the state House and Senate agree by separate votes on choices for the United States Senate, a process that would significantly reduce popular input to the choice.

Christopher Gore's choice was ultimately rejected in favor of a process whereby the House selected a slate of candidates, from which the Senate would choose one.

In 1789 Christopher Gore decided to stand for reelection, but lost, owing to strong anti-nationalist fervor in Boston at the time.

Christopher Gore managed to win a seat later, when a special election was held after resignations opened several seats.

Christopher Gore purchased Massachusetts war-related debts, and lobbied Massachusetts Congressmen for the US government to assume those as well.

Christopher Gore's windfall was realized when in 1790 the United States Congress, acting on a proposal made by Alexander Hamilton and supported by Christopher Gore's friend Rufus King, passed legislation that exchanged Continental and state paper for new US paper at face value.

The exact amount he made is unclear from the surviving documents: John Quincy Adams wrote that Christopher Gore's speculations made him the wealthiest lawyer in the country.

The success of Christopher Gore's speculations prompted him to enter a partnership with Craigie, William Duer and Daniel Parker in an attempt to acquire US foreign debt obligations on favorable terms.

Christopher Gore engaged in other ventures with these partners, but apparently carefully stayed with financial speculations, and avoided the partners' less successful land ventures.

Much of Christopher Gore's financial activity was mediated through the Bank of Massachusetts, where his father-in-law was a director.

Christopher Gore himself was elected to its board in 1785, when he became a shareholder.

Christopher Gore used the bank for most of his personal deposits, but drew on lines of credit for as much as several thousand dollars.

Hamilton recruited heavily in the Bank of Massachusetts, and Christopher Gore decided to make the move.

Christopher Gore sold his shares in the Massachusetts bank, and became a director of the Boston branch of the US Bank.

Christopher Gore purchased 200 shares in the new bank, a relatively large investment.

Christopher Gore was influential in making hiring decisions for the branch, and sought to merge state-chartered banks into the organization, arguing that only a nationally chartered bank could provide consistent and stable service.

Christopher Gore resigned from the board in 1794, citing the demands of his law practice.

Christopher Gore had a house built on the estate, most of which he operated as a gentleman farmer.

Christopher Gore controversially refused to resign from the state legislature, arguing that the state constitution's prohibitions against holding multiple offices did not apply to federal posts.

Christopher Gore eventually resigned the legislative seat under protest because of pressure from his fellow legislators.

Christopher Gore attempted several times to prosecute the French consul in Boston, Antoine Duplaine, for arming and operating privateers out of the Port of Boston, but he was stymied by local juries that sympathized with the French.

Christopher Gore promoted anti-French sentiment with political writings in Massachusetts newspapers.

Christopher Gore suggested to President Washington that someone be sent to England to negotiate with the British.

Christopher Gore used this break to briefly return to America and assess the condition of his Waltham estate, where the house had been largely destroyed by fire in 1799.

Rebecca Christopher Gore used their exposure to European country estates to design a lavish new building for their Waltham estate during their English sojourn.

Christopher Gore was active in the state Federalist Party organization, sitting on its secret central committee.

Christopher Gore resumed his law practice, in which he took on as a student Daniel Webster.

Christopher Gore argued Selfridge acted in self-defense; Selfridge was acquitted of murder by a jury whose foreman was Patriot and Federalist Paul Revere after fifteen minutes' deliberation.

Christopher Gore invested in a wide variety of businesses and infrastructure, spurring economic activity in the state.

Christopher Gore's investments ranged widely, including maritime insurance, bridges, locks, canals, and textiles.

Christopher Gore was a major investor in the Middlesex Canal, the Craigie Bridge, and the Boston Manufacturing Company, whose factory proving the single-site production of textiles was in Waltham near his estate.

The textile mill was a success, and Christopher Gore invested in the Merrimack Manufacturing Company.

When it decided to locate in what is Lowell, Massachusetts, Christopher Gore purchased shares in the Proprietors of Locks and Canals, which operated the Lowell canals.

Christopher Gore ran unsuccessfully for Governor of Massachusetts in 1807 and 1808 against a rising tide of Republicanism in the state, losing both times to moderate Republican James Sullivan.

The Federalists gained control of the state legislature in 1808 in a backlash against Republican economic policies, but Christopher Gore was criticized for his failure to aggressively support state protests against the Embargo Act of 1807, which had a major negative effect on the state's large merchant fleet.

Christopher Gore was in 1808 elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, where he successfully led Federalist efforts to ensure the selection of a Federalist slate of presidential electors.

Christopher Gore spearheaded actions to drive Senator John Quincy Adams from the Federalist Party over his support of Thomas Jefferson's foreign policy.

Christopher Gore led the Federalists to victory in 1809 against Sullivan's successor, Levi Lincoln Sr.

Christopher Gore ran against Gerry again in 1811, but lost in another acrimonious campaign.

Christopher Gore was granted an honorary law degree from Harvard in 1809.

Christopher Gore served on the college's Board of Overseers from 1810 to 1815 and as a Fellow from 1816 to 1820.

Christopher Gore served from May 5,1813, to May 30,1816, winning reelection to the seat in 1814.

Christopher Gore opposed the ongoing War of 1812 in these years, with his earlier diplomatic experience providing valuable knowledge to Federalist interests.

Christopher Gore expressed approval of the 1814 Hartford Convention in which the New England states aired grievances concerning Republican governance of the country and the conduct of the war.

Christopher Gore assented to the Treaty of Ghent that ended the war, but was unhappy that the nation had not gained anything from the war.

Christopher Gore remained active in the administration of Harvard, and was active in a number of organizations, including the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Christopher Gore was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1814.

Christopher Gore spent most of his later years at his country estate in Waltham, suffering from worsening rheumatoid arthritis that made walking increasingly difficult.

Christopher Gore's declining health and lack of social scene in Waltham led him in 1822 to return to Boston in the winters.

Christopher Gore died on March 1,1827, in Boston, and is buried in its Granary Burying Ground.

Christopher Gore's wife died in 1834; the couple had no children.

The major beneficiary of the Christopher Gore estate was Harvard, although bequests were made to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Massachusetts Historical Society.