1.

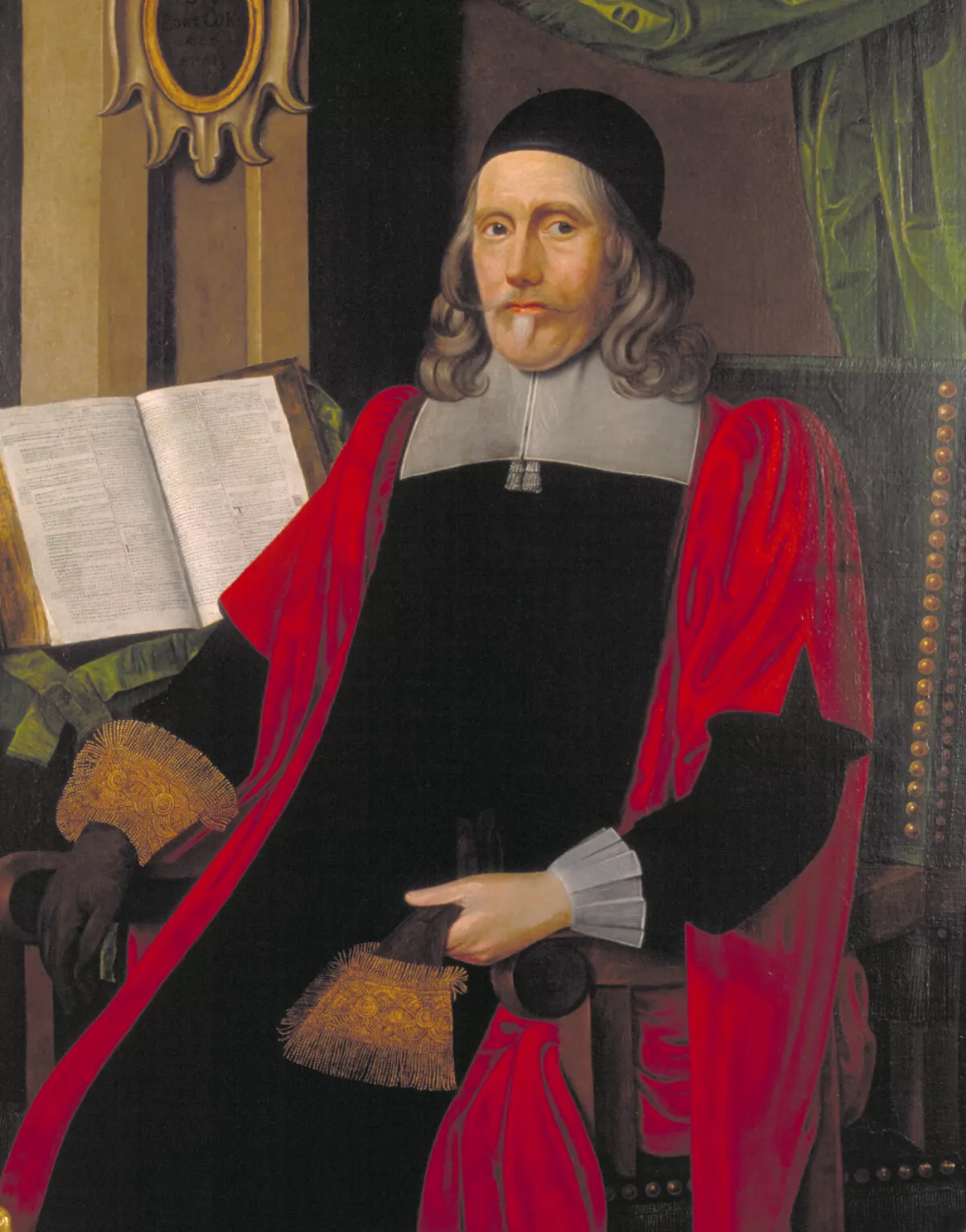

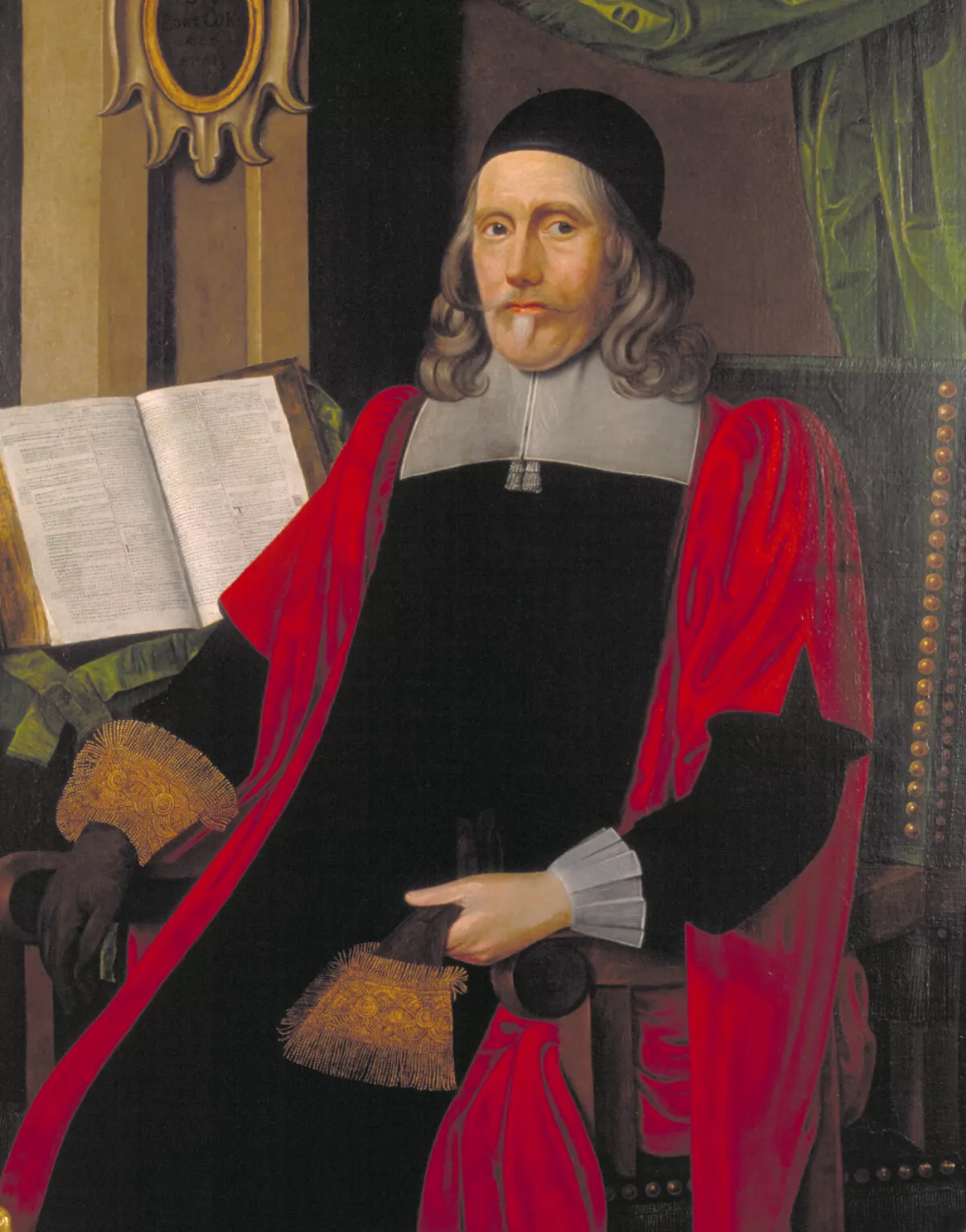

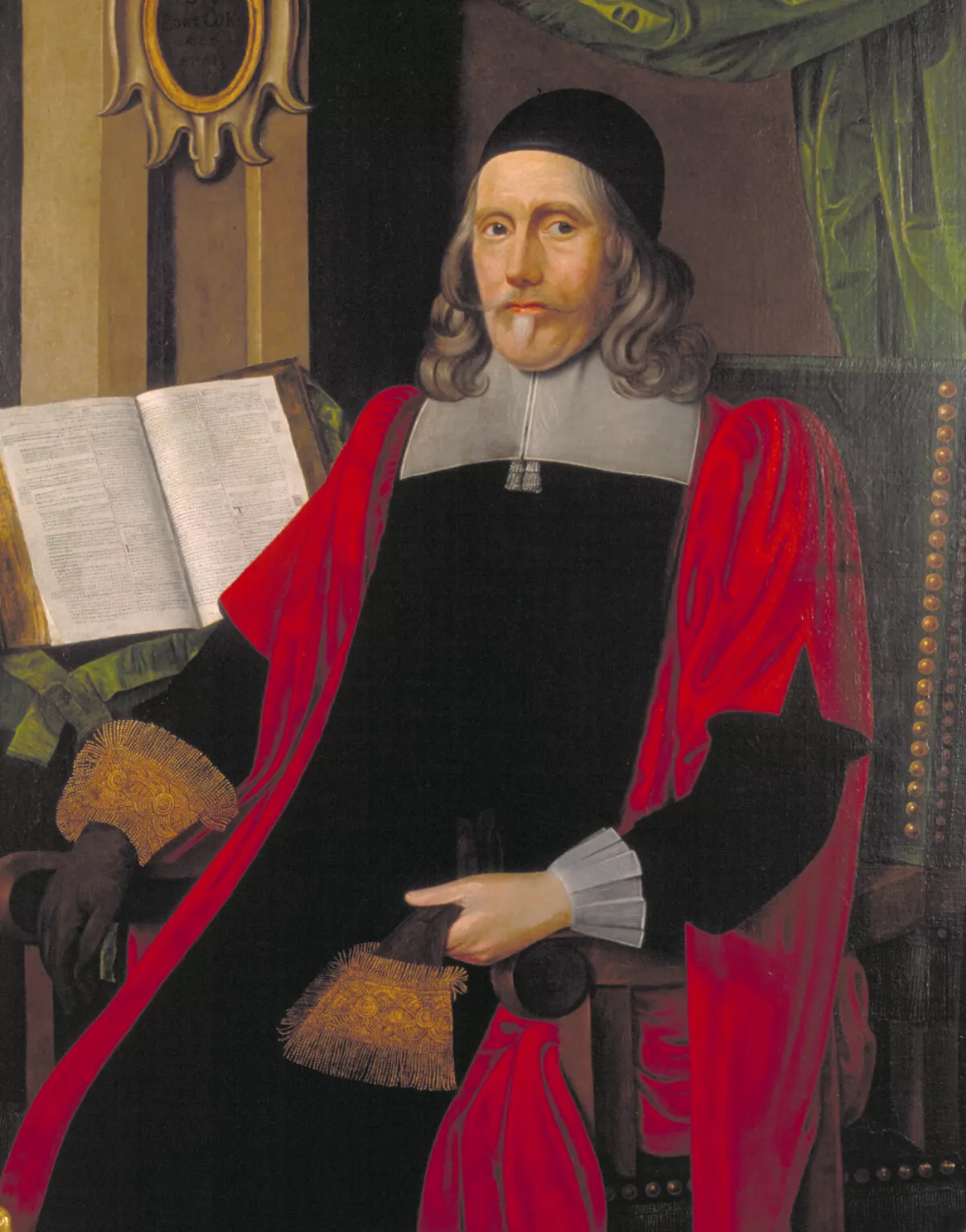

1. Sir Edward Coke was an English barrister, judge, and politician.

1.

1. Sir Edward Coke was an English barrister, judge, and politician.

Edward Coke is often considered the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras.

Edward Coke is best known in modern times for his Institutes, described by John Rutledge as "almost the foundations of our law", and his Reports, which have been called "perhaps the single most influential series of named reports".

Edward Coke's father, Robert Edward Coke, was a barrister and Bencher of Lincoln's Inn who built up a strong practice representing clients from his home area of Norfolk.

Edward Coke's mother, Winifred Knightley, came from a family even more intimately linked with the law than her husband.

Edward Coke had a tremendous influence on the Coke children: from Bozoun Coke learnt to "loathe concealers, prefer godly men and briskly do business with any willing client", something that shaped his future conduct as a lawyer, politician, and judge.

Edward Coke was taught at Norwich to value the "forcefulness of freedom of speech", something he later applied as a judge.

Edward Coke's biographers felt he had all the intelligence to be a good student, though a record of his academic achievements has not been found.

Edward Coke took little interest in the theatrical performances or other cultural events at the Inns, preferring to spend his time at the law courts in Westminster Hall, listening to the Serjeants argue.

Polson, a biographer of Edward Coke, suggests that this was due to his knowledge of the law, which "excited the Benchers".

Edward Coke's counsel had worked from an inaccurate English copy of the Latin statute of scandalum magnatum which had mistranslated several passages, forcing them to start the case anew.

The judge ruled that Denny's statement had indeed meant this, and from this position of strength Edward Coke forced a settlement.

Edward Coke was very proud of his actions in this case and later described it in his Reports as "an excellent point of learning in actions of slander".

Edward Coke's lectures were on the Statute of Uses, and his reputation was such that when he retired to his house after an outbreak of the plague, "nine Benchers, forty barristers, and others of the Inn accompanied him a considerable distance on his journey" in order to talk to him.

Edward Coke became involved in the now classic Shelley's Case in 1581, which created a rule in real property that is still used in some common law jurisdictions today; the case established Edward Coke's reputation as an attorney and case reporter.

Thanks to his work on their behalf, Edward Coke had earned the favour of the Dukes of Norfolk.

The political "old guard" began to change around the time Edward Coke became a Member of Parliament.

Edward Coke held the position only briefly; by the time he returned from a tour of Norfolk to discuss election strategy, he had been confirmed as Speaker of the House of Commons by the Privy Council, having been proposed by Francis Knollys and Thomas Heneage following his return to Parliament as MP for Norfolk.

Edward Coke continued talking until the end of the Parliamentary day in a filibuster action, granting a day of delay for the government.

Immediately afterwards, Edward Coke was summoned by the Queen, who made it clear that any action on the bills would be considered evidence of disloyalty.

Edward Coke reacted by becoming even more dogmatic in his actions on behalf of the Crown, and when Devereux approached the queen on Bacon's behalf, she replied that even Bacon's uncle [Lord Burghley] considered him the second best candidate, after Edward Coke.

Edward Coke was appointed in a time of particular difficulty; besides famine and the conflict with Spain, war had recently broken out in Ireland.

Edward Coke handled religious incidents such as the disputes between the Jesuits and the Church of England, personally interrogating John Gerard after his capture.

Edward Coke interviewed Hayward's licensing cleric, Samuel Harsnett, who complained that the dedication had been "foisted" on him by Devereux.

Edward Coke led the case for the government, and Devereux was found guilty and executed; the Earl of Southampton was reprieved.

Edward Coke was reconfirmed as Attorney General under James, and immediately found himself dealing with "a series of treasons, whether real or imaginary".

Edward Coke prosecuted Raleigh in that fashion because he had been asked to show Raleigh's guilt by the king, and as Attorney General, Coke was bound to obey.

In 1606 Edward Coke reported the Star Chamber case De Libellis Famosis, which ruled that truth was not a defence against an accusation of seditious libel, and held that ordinary common law courts could enforce this, a doctrine which thus outlived the Star Chamber after its abolition in 1642.

Edward Coke's conduct was noted by Johnson as "from the first, excellent; ever perfectly upright and fearlessly independent", although the convention of the day was that the judges held their positions only at the pleasure of the monarch.

Some assert that Edward Coke became Chief Justice due to his prosecutions of Raleigh and the Gunpowder Plot conspirators, but there is no evidence to support this; instead, it was traditional at the time that a retiring Chief Justice would be replaced with the Attorney General.

Edward Coke's changed position from Attorney General to Chief Justice allowed him to openly attack organisations he had previously supported.

The judges, particularly Edward Coke, began to unite with Parliament in challenging the High Commission.

Edward Coke had no official role, other than acting as a mediator between the two, but in the end, Fuller was convicted by the High Commission.

Edward Coke, speaking for the judges, argued that the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts was limited to cases where no temporal matters were involved and the rest left to the common law.

Edward Coke rejected this, stating that while the monarch was not subject to any individual, he was subject to the law.

Edward Coke was only saved from imprisonment by Cecil, who pleaded with the King to show leniency, which he granted.

Edward Coke's meaning has been disputed over the years; some interpret his judgment as referring to judicial review of statutes to correct misunderstandings which would render them unfair, while others argue he meant that the common law courts have the power to completely strike down those statutes they deem to be repugnant.

Whatever Edward Coke's meaning, after an initial period of application, Bonham's Case was thrown aside in favour of the growing doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty.

Now out of favour and with no chance of returning to the judiciary, Edward Coke was re-elected to Parliament as an MP, ironically by order of the King, who expected Edward Coke to support his efforts.

Edward Coke became a leading opposition MP, along with Robert Phelips, Thomas Wentworth and John Pym, campaigning against any military intervention and the marriage of the Prince of Wales and Maria Anna.

Edward Coke subsequently sat as MP for Coventry, Norfolk and Buckinghamshire.

When reminded that precedence belonged to Oxford "by vote of the House", Edward Coke persisted in giving Cambridge primacy.

Edward Coke used his role in Parliament as a leading opposition MP to attack patents, a system he had already criticised as a judge.

Edward Coke used his position in Parliament to attack these patents, which were, according to him, "now grown like hydras' heads; they grow up as fast as they are cut off".

Edward Coke succeeded in establishing the Committee of Grievances, a body chaired by him that abolished a large number of monopolies.

Edward Coke first adjourned Parliament and then forbade the Commons from discussing "matters of state at home or abroad".

Edward Coke was made High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire by the king in 1625, which prohibited him from sitting in Parliament until his term expired a year later.

Edward Coke then prepared the Resolutions, which later led to the Habeas Corpus Act 1679.

Edward Coke told the Lords that "Imprisonment in law is a civil death [and] a prison without a prefixed time is a kind of hell".

Edward Coke undertook the central role in framing and writing the Petition of Right.

When Parliament was dissolved in 1629, Charles decided to govern without one, and Edward Coke retired to his estate at Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire, about 20 miles west of London, spending his time making revisions to his written works.

Edward Coke remained a lifelong Anglican and was buried in St Mary's Church, Tittleshall, Norfolk.

Edward Coke's grave is covered by a marble monument with his effigy lying on it in full judicial robes, surrounded by eight shields holding his coat of arms.

Edward Coke was buried beside his first wife, who was called his "first and best wife" by his daughter Anne; his second wife died in 1646.

Edward Coke had two children with his second wife, both daughters: Elizabeth and Frances Edward Coke, Viscountess Purbeck.

Edward Coke's faults were the faults of his time, his excellencies those of all time.

Edward Coke was diffuse; he loved metaphor, literary quibbles and verbal conceits; so did Bacon, and so did Shakespeare.

Edward Coke began reporting cases in the traditional manner, by copying out and repeating cases found in earlier law reports, such as those of Edmund Plowden.

Five more volumes were published until 1615, but Edward Coke died before he could publish a single-bound copy.

John Rutledge later wrote that "Edward Coke's Institutes seems to be almost the foundations of our law", while Jefferson stated that "a sounder Whig never wrote more profound learning in the orthodox doctrine of British liberties".

Edward Coke argued that the judges of the common law were those most suited to making law, followed by Parliament, and that the monarch was bound to follow any legal rules.

Edward Coke's position meant that certainty of the law and intellectual beauty was the way to see if a law was just and correct, and that the system of law could eventually become sophisticated enough to be predictable.

Edward Coke argued that this did not necessarily create judicial discretion to alter it, and that proper did not necessarily equal perfect.

Edward Coke was particularly influential in the United States both before and after the American War of Independence.

Edward Coke was a strong influence on and mentor of Roger Williams, an English theologian who founded the Rhode Island colony in North America and was an early proponent of the doctrine of separation of church and state.

Edward Coke was noted as deriving great enjoyment from and working hard at the law, but enjoying little else.

Edward Coke was versed in the Latin classics and maintained a sizeable estate, but the law was his primary concern.

Francis Bacon, his main competitor, was known as a philosopher and man of learning, but Edward Coke had no interest in such subjects.

Notably, when given a copy of the Novum Organum by Bacon, Edward Coke wrote puerile insults in it.

Edward Coke was regarded, even during his life, as the greatest lawyer of his time in both reputation and monetary success.

Francis Watt, writing in the Juridical Review, portrays this as Edward Coke's strongest characteristic as a lawyer: that he was a man who "having once taken up a point or become engaged in a case, believes in it with all his heart and soul, whilst all the time conscious of its weakness, as well as ready to resort to every device to bolster it up".

Edward Coke made a fortune from purchasing estates with clouded titles at a discount, whereupon, through his knowledge of the intricacies of property law, he would clear the titles on the acquired properties to his favour.

James I claimed that Edward Coke "had already as much land as it was proper a subject should possess".

The story goes that Edward Coke requested the King's permission to just "add one acre more" to his holdings, and upon approval proceeded to purchase the fine estate of Castle Acre Priory in Norfolk, one of the most expensive "acres" in the land.