1.

1. Erasmus was an important figure in classical scholarship who wrote in a spontaneous, copious and natural Latin style.

1.

1. Erasmus was an important figure in classical scholarship who wrote in a spontaneous, copious and natural Latin style.

Erasmus wrote On Free Will, The Praise of Folly, The Complaint of Peace, Handbook of a Christian Knight, On Civility in Children, Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style and many other popular and pedagogical works.

Erasmus lived against the backdrop of the growing European religious reformations.

Erasmus developed a biblical humanistic theology in which he advocated the religious and civil necessity both of peaceable concord and of pastoral tolerance on matters of indifference.

Erasmus remained a member of the Catholic Church all his life, remaining committed to reforming the church from within.

Erasmus promoted what he understood as the traditional doctrine of synergism, which some prominent reformers such as Martin Luther and John Calvin rejected in favor of the doctrine of monergism.

The year of Erasmus' birth is unclear: in later life he calculated his age as if born in 1466, but frequently his remembered age at major events actually implies 1469.

Erasmus's mother was Margaretha Rogerius, the daughter of a doctor from Zevenbergen.

Erasmus was given the highest education available to a young commoner of his day, in a series of private, monastic or semi-monastic schools.

Erasmus was exposed there to the Devotio moderna movement and the Brethren's famous book The Imitation of Christ but resented the harsh rules and strict methods of the religious brothers and educators.

Rogerus, who became prior at Stein in 1504, and Erasmus corresponded over the years, with Rogerus demanding Erasmus return after his studies were complete.

For instance, Erasmus became an intimate friend of an Italian humanist Publio Fausto Andrelini, poet and "professor of humanity" in Paris.

Erasmus was particularly impressed by the Bible teaching of John Colet, who pursued a preaching style more akin to the church fathers than the Scholastics.

Erasmus left London with a full purse from his generous friends, to allow him to complete his studies.

In 1502, Erasmus went to Brabant, ultimately to the university at Louvain.

For Erasmus' second visit, he spent over a year staying at recently married Thomas More's house, now a lawyer and Member of Parliament, honing his translation skills.

Erasmus preferred to live the life of an independent scholar and made a conscious effort to avoid any actions or formal ties that might inhibit his individual freedom.

In England Erasmus was approached with prominent offices but he declined them all, until the King himself offered his support.

Erasmus was inclined, but eventually did not accept and longed for a stay in Italy.

Erasmus's discovery en route of Lorenzo Valla's New Testament Notes was a major event in his career and prompted Erasmus to study the New Testament using philology.

Erasmus travelled on to Venice, working on an expanded version of his Adagia at the Aldine Press of the famous printer Aldus Manutius, advised him which manuscripts to publish, and was an honorary member of the graecophone Aldine "New Academy".

Aldus wrote that Erasmus could do twice as much work in a given time as any other man he had ever met.

Erasmus found employment tutoring and escorting Scottish nobleman Alexander Stewart, the 24-year old Archbishop of St Andrews, through Padua, Florence, and Siena Erasmus made it to Rome in 1509, visiting some notable libraries and cardinals, but having a less active association with Italian scholars than might have been expected.

On his trip over the Alps via Splugen Pass, and down the Rhine toward England, Erasmus began to compose The Praise of Folly.

In 1510, Erasmus arrived at More's bustling house, was confined to bed to recover from his recurrent illness, and wrote The Praise of Folly, which was to be a best-seller.

Erasmus assisted his friend John Colet by authoring Greek textbooks and securing members of staff for the newly established St Paul's School and was in contact when Colet gave his notorious 1512 Convocation sermon which called for a reformation of ecclesiastical affairs.

In 1511, the University of Cambridge's chancellor, John Fisher, arranged for Erasmus to be the Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity, though whether he actually was accepted for it or took it up is contested by historians.

Erasmus studied and taught Greek and researched and lectured on Jerome.

Erasmus mainly stayed at Queens' College while lecturing at the university, between 1511 and 1515.

Erasmus' rooms were located in the "" staircase of Old Court.

Erasmus suffered from poor health and was especially concerned with heating, clean air, ventilation, draughts, fresh food and unspoiled wine: he complained about the draughtiness of English buildings.

Erasmus complained that Queens' College could not supply him with enough decent wine.

In 1516, Erasmus accepted an honorary position as a Councillor to Charles V with an annuity of 200 guilders, rarely paid, and tutored Charles' brother, the teenage future Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand of Hapsburg.

In 1516, Erasmus published the first edition of his scholarly Latin-Greek New Testament with annotations, his complete works of Jerome, and The Education of a Christian Prince for Charles and Ferdinand.

On being asked by Jean Le Sauvage, former Chancellor of Brabant and now Chancellor of Burgundy, Erasmus wrote The Complaint of Peace.

In 1518, Erasmus was diagnosed with the plague; despite the danger, he was taken in and cared for in the home of his Flemish friend and publisher Dirk Martens in Antwerp for a month and recovered.

Erasmus stayed in various locations including Anderlecht in the summer of 1521.

From 1514, Erasmus regularly traveled to Basel to coordinate the printing of his books with Froben.

Erasmus developed a lasting association with the great Basel publisher Johann Froben and later his son Hieronymus Froben who together published over 200 works with Erasmus, working with expert scholar-correctors who went on to illustrious careers.

Erasmus was weary of the controversies and hostility at Louvain, and feared being dragged further into the Lutheran controversy.

Erasmus agreed to be the Froben press' literary superintendent writing dedications and prefaces for an annuity and profit share.

In Spring early 1530 Erasmus was bedridden for three months with an intensely painful infection, likely carbunculosis, that, unusually for him, left him too ill to work.

Erasmus wrote several important non-political works under the surprising patronage of Thomas Bolyn: his Ennaratio triplex in Psalmum XXII or Triple Commentary on Psalm 23 ; his catechism to counter Luther Explanatio Symboli or A Playne and Godly Exposition or Declaration of the Commune Crede which sold out in three hours at the Frankfurt Book Fair, and Praeparatio ad mortem or Preparation for Death which would be one of Erasmus' most popular and most hijacked works.

Erasmus had remained loyal to Roman Catholicism, but biographers have disagreed whether to treat him as an insider or an outsider.

Erasmus was buried with great ceremony in the Basel Minster.

Erasmus had a distinctive manner of thinking, a Catholic historian suggests: one that is capacious in its perception, agile in its judgments, and unsettling in its irony with "a deep and abiding commitment to human flourishing".

Erasmus often wrote in a highly ironical idiom, especially in his letters, which makes them prone to different interpretations when taken literally rather than ironically.

Erasmus frequently wrote about controversial subjects using the dialogue to avoid direct statements clearly attributable to himself.

Erasmus conquered by gentleness; Erasmus conquered by kindness; he conquered by truth itself.

Erasmus was not an absolute pacifist but promoted political pacificism and religious Irenicism.

Erasmus promoted and was present at the Field of Cloth of Gold, and his wide-ranging correspondence frequently related to issues of peacemaking.

Erasmus saw a key role of the Church in peacemaking by arbitration and mediation, and the office of the Pope was necessary to rein in tyrannical princes and bishops.

Erasmus was highly critical of the warlike way of important European princes of his era, including some princes of the church.

Erasmus believed that these princes "collude in a game, of which the outcome is to exhaust and oppress the commonwealth".

Erasmus spoke more freely about this matter in letters sent to his friends like Thomas More, Beatus Rhenanus and Adrianus Barlandus: a particular target of his criticisms was the Emperor Maximilian I, whom Erasmus blamed for allegedly preventing the Netherlands from signing a peace treaty with Guelders and other schemes to cause wars in order to extract money from his subjects.

Erasmus referred to his irenical disposition in the Preface to On Free Will as a secret inclination of nature that would make him even prefer the views of the Sceptics over intolerant assertions, though he sharply distinguished adiaphora from what was uncontentiously explicit in the New Testament or absolutely mandated by Church teaching.

Concord demanded unity and assent: Erasmus was anti-sectarian as well as non-sectarian.

The centrality of Christian concord to Erasmus' theology contrasted with the insistence of Martin Luther and, for example, later English Puritans, that truth naturally would create discord and opposition.

Certain works of Erasmus laid a foundation for religious toleration of private opinions and ecumenism.

Erasmus had been privately involved in early attempts to protect Luther and his sympathisers from charges of heresy.

Erasmus wrote Inquisitio de fide to say that the Lutherans were not formally heretics: he pushed back against the willingness of some theologians to cry heresy fast in order to enforce their views in universities and at inquisitions.

Erasmus' pacificism included a particular dislike for sedition, which caused warfare:.

In 1516, Erasmus wrote, "It is the part of a Christian prince to regard no one as an outsider unless he is a nonbeliever, and even on them he should inflict no harm", which entails not attacking outsiders, not taking their riches, not subjecting them to political rule, no forced conversions, and keeping promises made to them.

In common with his times, Erasmus regarded the Jewish and Islamic religions as Christian heresies rather than separate religions, using the inclusive term half-Christian for the latter.

Several scholars have identified cases where Erasmus' comments appear to go beyond theological anti-Judaism into slurs or approving to an extent certain anti-semitic policies, though there is some controversy.

Erasmus had various other piecemeal arguments against slavery: for example, that it was not legitimate to enslave people taken in an unjust war, but it was not a subject that occupied him.

In 1530, Erasmus published a new edition of the orthodox treatise of Algerus against the heretic Berengar of Tours in the eleventh century.

Erasmus added a dedication, affirming his belief in the reality of the Body of Christ after consecration in the Eucharist, commonly referred to as transubstantiation.

However, Erasmus found the scholastic formulation of transubstantiation to stretch language past its breaking point.

Erasmus wrote several notable pastoral books and pamphlets on sacraments, always looking through rather than at the rituals or forms:.

At the height of his literary fame, Erasmus was called upon to take one side, but public partisanship was foreign to his beliefs, nature, and habits.

Erasmus believed that his work had commended itself to the religious world's best minds and dominant powers.

Erasmus chose to write in Latin, the languages of scholars.

Erasmus did not build a large body of supporters in the unlettered; his critiques reached a small but elite audience.

Erasmus was scandalized by superstitions, such as that if you were buried in a Franciscan habit, you would go directly to heaven.

Erasmus advocated various reforms, including a ban on taking orders until the 30th year, the closure of corrupt and smaller monasteries, respect for bishops, requiring work, not begging the downplaying of monastic hours, fasts and ceremonies, and a less mendacious approach to gullible pilgrims and tenants.

Erasmus believed the only vow necessary for Christians should be the vow of Baptism, and others such as the vows of the evangelical counsels, while admirable in intent and content, were now mainly counter-productive.

However, Erasmus frequently commended the evangelical counsels for all believers, and with more than lip service: for example, the first adage of his reputation-establishing Adagia was Between friends all is common, where he tied common ownership with the teachings of classical philosophers and Christ.

Erasmus did have significant support and contact with reform-minded friars, including Franciscans such as Jean Vitrier and Cardinal Cisneros, and Dominicans such as Cardinal Cajetan the former master of the Order of Preachers.

Erasmus was one of many scandalized by the sale of indulgences to fund Pope Leo X's projects.

Erasmus declined to commit himself, arguing his usual "small target" excuse, that to do so would endanger the cause of which he regarded as one of his purposes in life.

When Erasmus declined to support him, the "straightforward" Luther became angered that Erasmus was avoiding the responsibility due either to cowardice or a lack of purpose.

Erasmus replied to this in his lengthy two volume Hyperaspistes and other works, which Luther ignored.

In 1529, Erasmus wrote "An epistle against those who falsely boast they are Evangelicals" to Gerardus Geldenhouwer.

Erasmus wrote books against aspects of the teaching, impacts or threats of several other Reformers:.

However, Erasmus maintained friendly relations with other Protestants, notably the irenic Melanchthon and Albrecht Duerer.

Erasmus was sympathetic to a kind of epistemological Scepticism:.

Historian Kirk Essary has noted that from his earliest to last works Erasmus "regularly denounced the Stoics as specifically unchristian in their hardline position and advocacy of apatheia": warm affection and an appropriately fiery heart being inalienable parts of human sincerity; however historian Ross Dealy sees Erasmus' decrial of other non-gentle "perverse affections" as having Stoical roots.

Erasmus wrote in terms of a tri-partite nature of man, with the soul the seat of free will:.

Erasmus did not have a metaphysical bone in his frail body, and had no real feeling for the philosophical concerns of scholastic theology.

Ultimately, Erasmus personally owned Aquinas' Summa theologiae, the Catena aurea and his commentary on Paul's epistles.

Erasmus approached classical philosophers theologically and rhetorically: their value was in how they pre-saged, explained or amplified the unique teachings of Christ : the philosophia Christi.

In works such as his Enchiridion, The Education of a Christian Prince and the Colloquies, Erasmus developed his idea of the philosophia Christi, a life lived according to the teachings of Jesus taken as a spiritual-ethical-social-political-legal philosophy:.

Three key distinctive features of the spirituality Erasmus proposed are accommodation, inverbation, and scopus christi.

For Erasmus, accommodation is a universal concept: humans must accommodate each other, must accommodate the church and vice versa, and must take as their model how Christ accommodated the disciples in his interactions with them, and accommodated humans in his incarnation; which in turn merely reflects the eternal mutual accommodation within the Trinity.

Erasmus wrote that most of his original works, from satires to paraphrases, were essentially the same themes packaged for different audiences.

Since the Gospels become in effect like sacraments, for Erasmus reading them becomes a form of prayer which is spoiled by taking single sentences in isolation and using them as syllogisms.

Several scholars have suggested Erasmus wrote as an evangelist not an academic theologian.

Apart from these programmatic works, Erasmus produce a number of prayers, sermons, essays, masses and poems for specific benefactors and occasions, often on topics where Erasmus and his benefactor agreed.

Erasmus often set himself the challenge of formulating positive, moderate, non-superstitious versions of contemporary Catholic practices that might be more acceptable both to scandalized Catholics and Protestants of good will: the better attitudes to the sacraments, saints, Mary, indulgences, statues, scriptural ignorance and fanciful Biblical interpretation, prayer, dietary fasts, external ceremonialism, authority, vows, docility, submission to Rome, etc.

For example, in his Paean in Honour of the Virgin Mary Erasmus elaborated his theme that the Incarnation had been hinted far and wide, which could impact the theology of the fate of the remote unbaptized and grace, and the place of classical philosophy:.

Erasmus was the most popular, most printed and arguably most influential author of the early sixteenth century, read in all nations in the West and frequently translated.

Erasmus usually wrote books in particular classical literary genres with their different rhetorical conventions: complaint, diatribe, dialogue, encomium, epistle, commentary, liturgy, sermon, etc.

Erasmus wrote or answered up to 40 letters per day, usually waking early in the morning and writing them in his own hand.

Erasmus's writing method was to make notes on whatever he was reading, categorized by theme: he carted these commonplaces in boxes that accompanied him.

Erasmus is noted for his extensive scholarly editions of the New Testament in Latin and Greek, and the complete works of numerous Church Fathers.

Erasmus was given the sobriquet "Prince of the Humanists", and has been called "the crowning glory of the Christian humanists".

Erasmus has been called "the most illustrious rhetorician and educationalist of the Renaissance".

Erasmus was never judged and declared a heretic by the Catholic Church, during his lifetime or after: a semi-secret trial in Vallodolid Spain, in 1527 found him not to be a heretic, and he was sponsored and protected by Popes and Bishops.

Erasmus was a quite sickly man and frequently worked from his sickbed.

Erasmus's digestion gave him trouble: he was intolerant of fish, beer and some wines, which were the standard diet for members of religious orders; he eventually died following an attack of dysentery.

Erasmus suffered kidney stones from his time in Venice and, in late life, with gout In 1514, he suffered a fall from his horse and injured his back.

Erasmus preferred warm and soft garments: according to one source, he arranged for his clothing to be stuffed with fur to protect him against the cold, and his habit counted with a collar of fur which usually covered his nape.

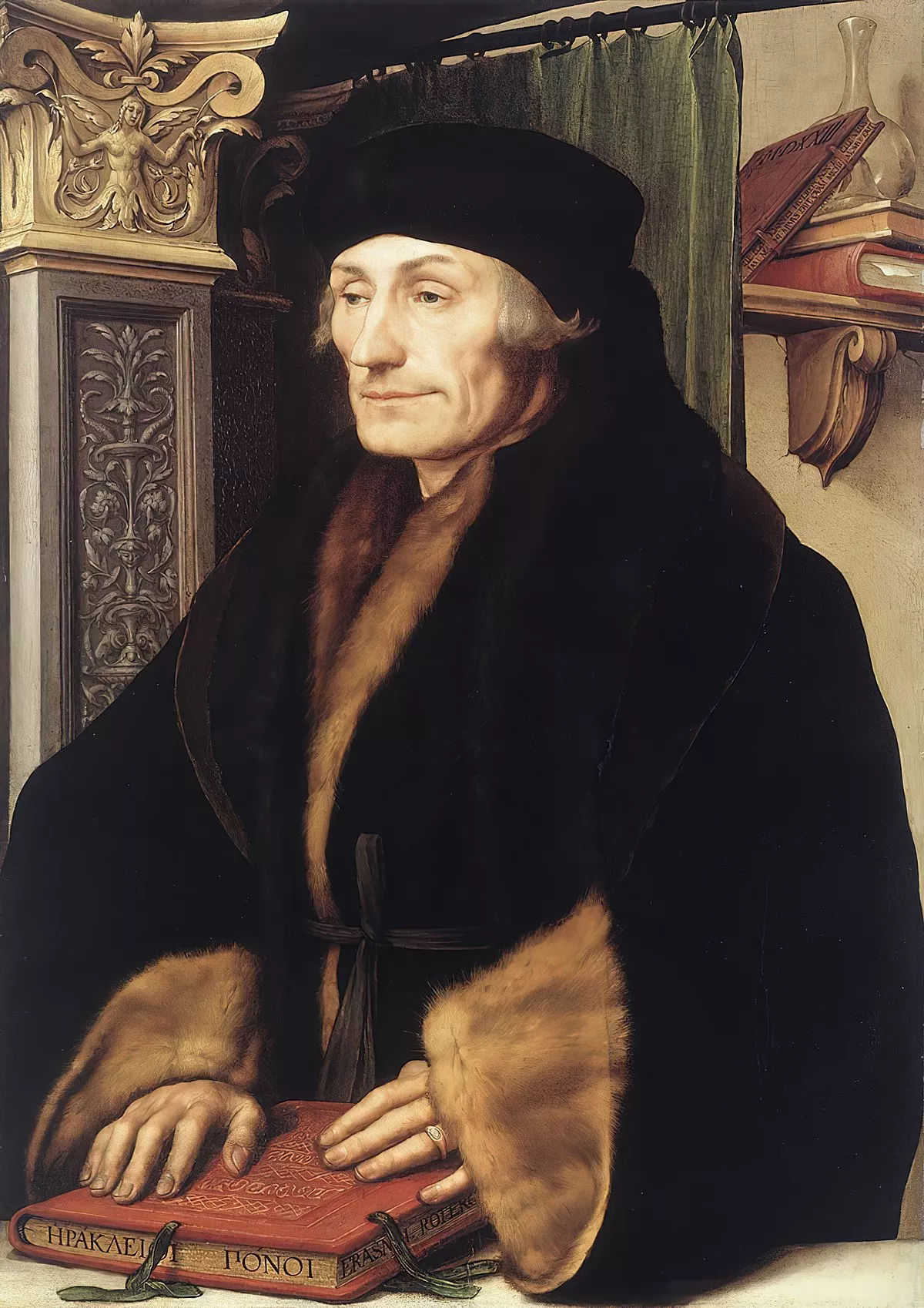

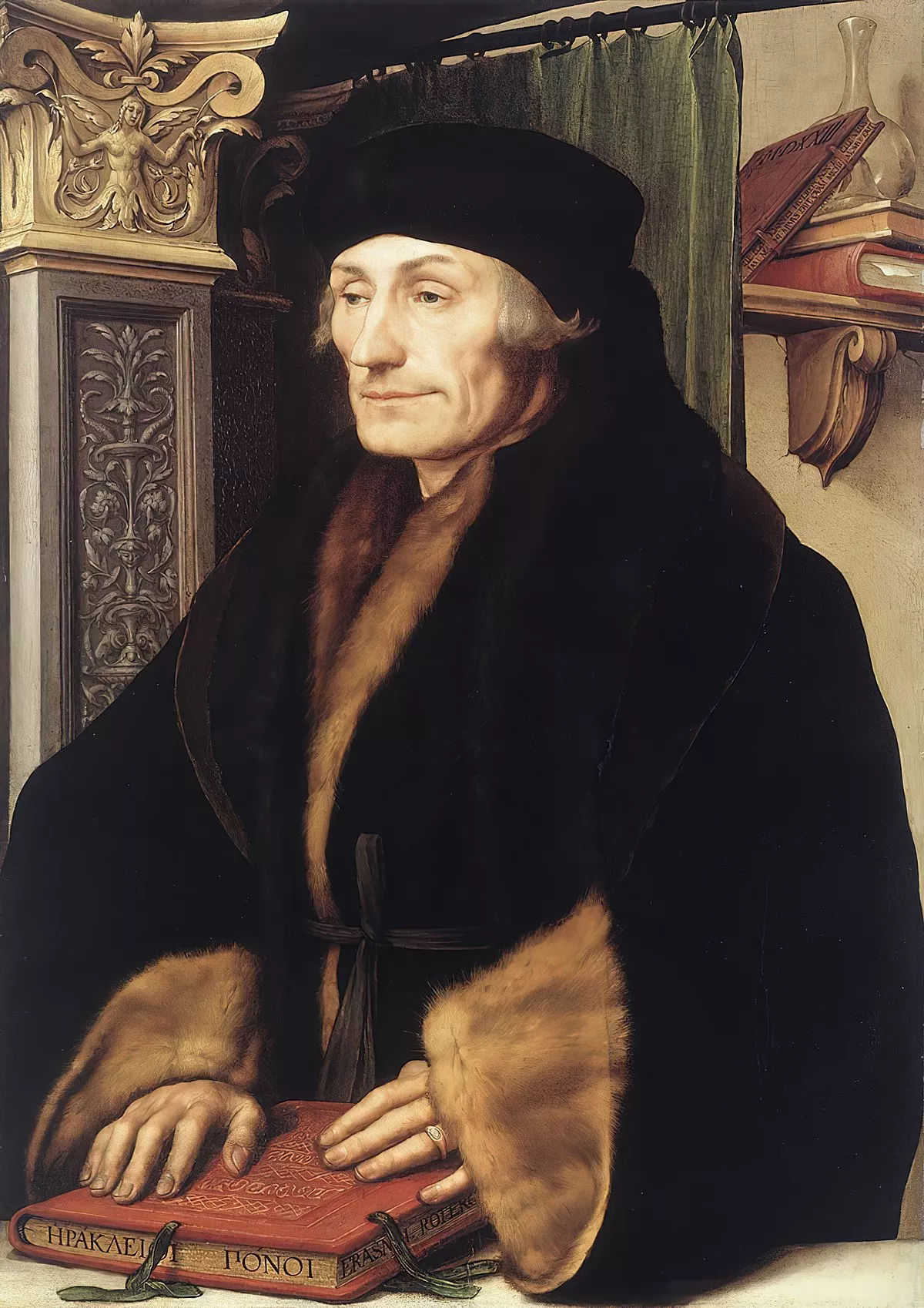

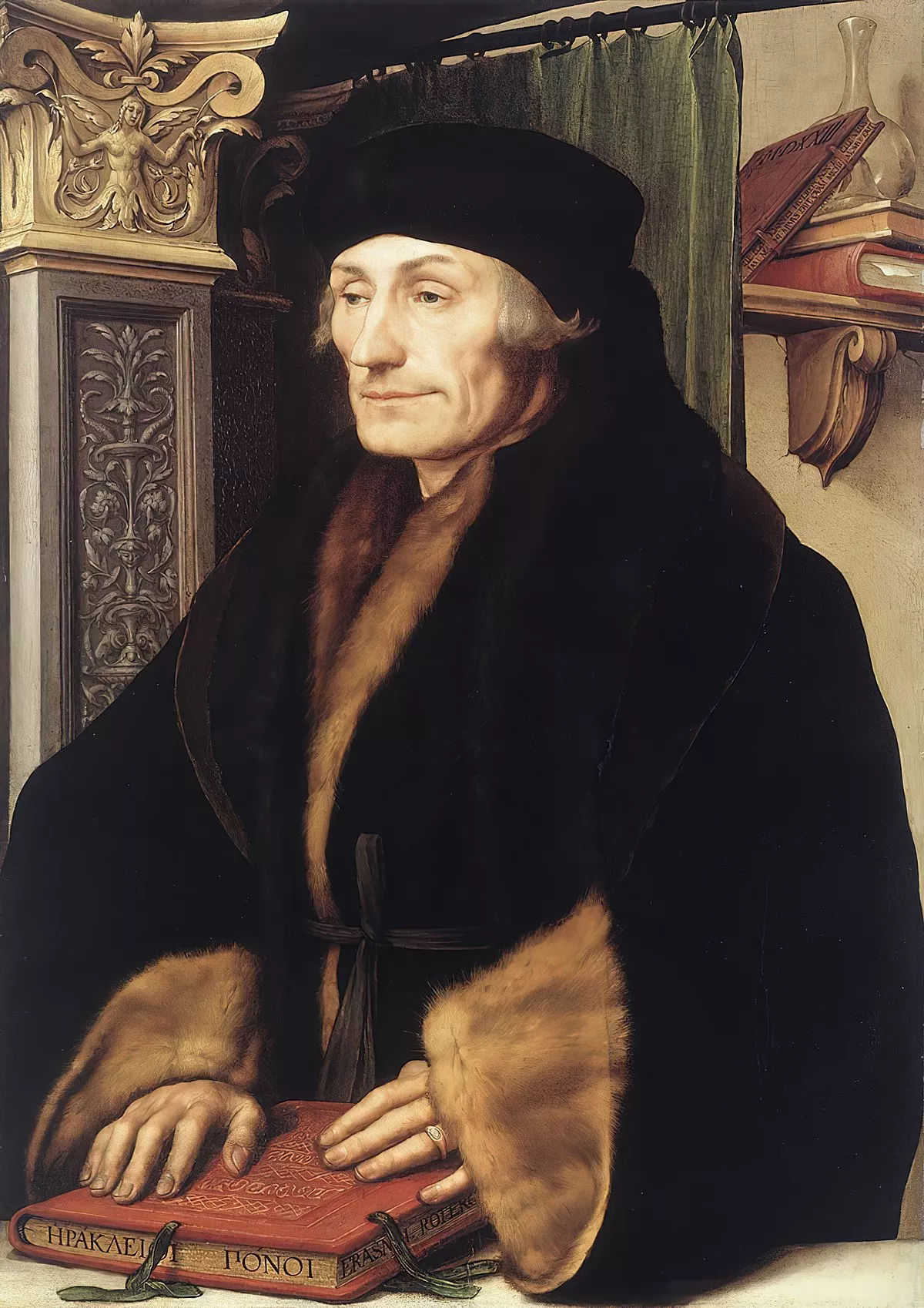

All Erasmus' portraits show him wearing a knitted scholar's bonnet.

Erasmus chose the Roman god of borders and boundaries Terminus as a personal symbol and had a signet ring with a herm he thought depicted Terminus carved into a carnelian.

The herm became part of the Erasmus branding at Froben, and is on his tombstone.

The diamond ring Erasmus wears in the famous Holbein portrait was a gift from his long-time friend and corespondent, Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio, as a "memorial of our friendship".

In 1928, the site of Erasmus' grave was dug up, and a body identified in the bones and examined.