1.

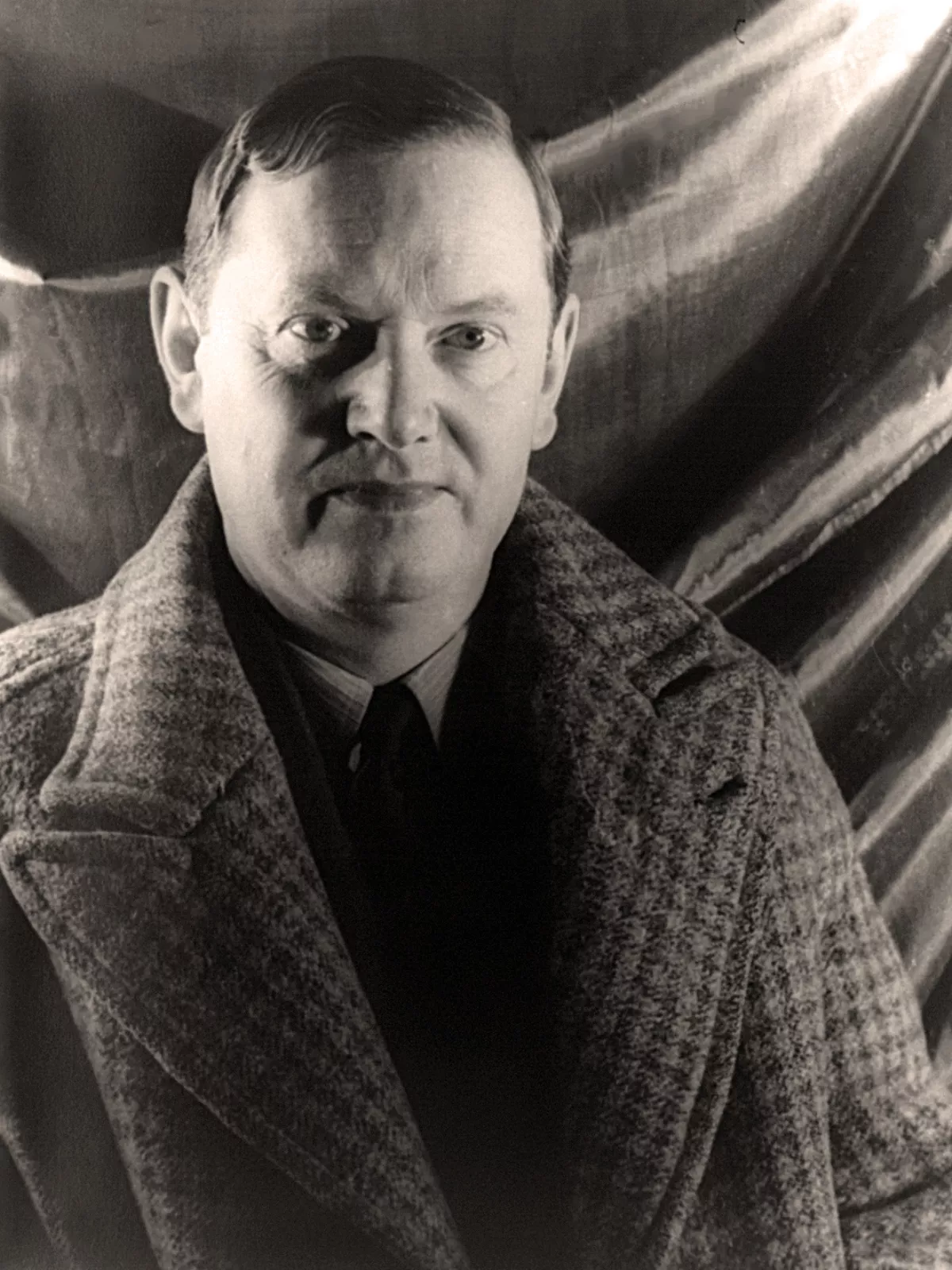

1. Arthur Evelyn St John Waugh was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was a prolific journalist and book reviewer.

1.

1. Arthur Evelyn St John Waugh was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was a prolific journalist and book reviewer.

Evelyn Waugh is recognised as one of the great prose stylists of the English language in the 20th century.

Evelyn Waugh worked briefly as a schoolmaster before he became a full-time writer.

Evelyn Waugh travelled extensively in the 1930s, often as a special newspaper correspondent; he reported from Abyssinia at the time of the 1935 Italian invasion.

Evelyn Waugh served in the British armed forces throughout the Second World War, first in the Royal Marines and then in the Royal Horse Guards.

Evelyn Waugh was a perceptive writer who used the experiences and the wide range of people whom he encountered in his works of fiction, generally to humorous effect.

Evelyn Waugh's detachment was such that he fictionalised his own mental breakdown which occurred in the early 1950s.

Evelyn Waugh converted to Catholicism in 1930 after his first marriage failed.

Evelyn Waugh displayed to the world a mask of indifference, but he was capable of great kindness to those whom he considered his friends.

Arthur Evelyn St John Waugh was born on 28 October 1903 to Arthur Waugh and Catherine Charlotte Raban, into a family with English, Scottish, Welsh, Irish and Huguenot origins.

Evelyn Waugh's grandson Alexander Waugh was a country medical practitioner, who bullied his wife and children and became known in the Waugh family as "the Brute".

Evelyn Waugh had married Catherine Raban in 1893; their first son Alexander Raban Waugh was born on 8 July 1898.

In 1907, the Evelyn Waugh family left Hillfield Road for Underhill, a house which Arthur had built in North End Road, Hampstead, close to Golders Green, then a semi-rural area of dairy farms, market gardens and bluebell woods.

Evelyn received his first school lessons at home, from his mother, with whom he formed a particularly close relationship; his father, Arthur Waugh, was a more distant figure, whose close bond with his elder son, Alec, was such that Evelyn often felt excluded.

In September 1910, Evelyn Waugh began as a day pupil at Heath Mount preparatory school.

Evelyn Waugh spent six relatively contented years at Heath Mount; on his own assertion he was "quite a clever little boy" who was seldom distressed or overawed by his lessons.

Physically pugnacious, Evelyn Waugh was inclined to bully weaker boys; among his victims was the future society photographer Cecil Beaton, who never forgot the experience.

In 1914, after the First World War began, Waugh and other boys from the Boy Scout Troop of Heath Mount School were sometimes employed as messengers at the War Office; Evelyn loitered about the War Office in hope of glimpsing Lord Kitchener, but never did.

At Midsomer Norton, Evelyn Waugh became deeply interested in high Anglican church rituals, the initial stirrings of the spiritual dimension that later dominated his perspective of life, and he served as an altar boy at the local Anglican church.

The public sensation caused by Alec's novel so offended the school that it became impossible for Evelyn Waugh to go there.

Evelyn Waugh soon overcame his initial aversion to Lancing, settled in and established his reputation as an aesthete.

The end of the war saw the return to the school of younger masters such as J F Roxburgh, who encouraged Waugh to write and predicted a great future for him.

Evelyn Waugh started a novel of school life, untitled, but abandoned the effort after writing around 5,000 words.

Evelyn Waugh ended his schooldays by winning a scholarship to read Modern History at Hertford College, Oxford, and left Lancing in December 1921.

Evelyn Waugh was writing to old friends at Lancing about the pleasures of his new life; he informed Tom Driberg: "I do no work here and never go to Chapel".

Evelyn Waugh wrote reports on Union debates for both Oxford magazines, Cherwell and Isis, and he acted as a film critic for Isis.

Evelyn Waugh became secretary of the Hertford College debating society, "an onerous but not honorific post", he told Driberg.

Acton and Howard rapidly became the centre of an avant-garde circle known as the Hypocrites' Club, whose artistic, social and homosexual values Evelyn Waugh adopted enthusiastically; he later wrote: "It was the stamping ground of half my Oxford life".

Evelyn Waugh began drinking heavily, and embarked on the first of several homosexual relationships, the most lasting of which were with Hugh Lygon, Richard Pares and Alastair Graham.

Evelyn Waugh continued to write reviews and short stories for the university journals, and developed a reputation as a talented graphic artist, but formal study largely ceased.

When Cruttwell advised him to mend his ways, Evelyn Waugh responded in a manner which, he admitted later, was "fatuously haughty"; from then on, relations between the two descended into mutual hatred.

Evelyn Waugh continued the feud long after his Oxford days by using Cruttwell's name in his early novels for a succession of ludicrous, ignominious or odious minor characters.

Evelyn Waugh's dissipated lifestyle continued into his final Oxford year, 1924.

Evelyn Waugh did just enough work to pass his final examinations in the summer of 1924 with a third-class.

Back at home, Evelyn Waugh began a novel, The Temple at Thatch, and worked with some of his fellow Hypocrites on a film, The Scarlet Woman, which was shot partly in the gardens at Underhill.

Evelyn Waugh spent much of the rest of the summer in the company of Alastair Graham; after Graham departed for Kenya, Waugh enrolled for the autumn at a London art school, Heatherley's.

Evelyn Waugh began at Heatherley's in late September 1924, but became bored with the routine and quickly abandoned his course.

Evelyn Waugh spent weeks partying in London and Oxford before the overriding need for money led him to apply through an agency for a teaching job.

Evelyn Waugh took with him the notes for his novel, The Temple at Thatch, intending to work on it in his spare time.

Evelyn Waugh had meantime sent the early chapters of his novel to Acton for assessment and criticism.

Acton's reply was so coolly dismissive that Evelyn Waugh immediately burnt his manuscript; shortly afterwards, before he left North Wales, he learned that the Moncrieff job had fallen through.

Evelyn Waugh considered alternative careers in printing or cabinet-making, and attended evening classes in carpentry at Holborn Polytechnic while continuing to write.

Evelyn Waugh began working on a comic novel; after several temporary working titles this became Decline and Fall.

In December 1927, Waugh and Evelyn Gardner became engaged, despite the opposition of Lady Burghclere, who felt that Waugh lacked moral fibre and kept unsuitable company.

Less pleasing to Evelyn Waugh were the Times Literary Supplements references to him as "Miss Evelyn Waugh".

Evelyn Waugh finished his second novel, Vile Bodies, and wrote articles including one for the Daily Mail on the meaning of the marriage ceremony.

On 29 September 1930, Evelyn Waugh was received into the Catholic Church.

Evelyn Waugh had lost his Anglicanism at Lancing and had led an irreligious life at Oxford, but there are references in his diaries from the mid-1920s to religious discussion and regular churchgoing.

On 22 December 1925, Evelyn Waugh wrote: "Claud and I took Audrey to supper and sat up until 7 in the morning arguing about the Roman Church".

In 1949, Evelyn Waugh explained that his conversion followed his realisation that life was "unintelligible and unendurable without God".

On 10 October 1930, Evelyn Waugh, representing several newspapers, departed for Abyssinia to cover the coronation of Haile Selassie.

Evelyn Waugh reported the event as "an elaborate propaganda effort" to convince the world that Abyssinia was a civilised nation which concealed the fact that the emperor had achieved power through barbarous means.

Evelyn Waugh travelled on via several staging-posts to Boa Vista in Brazil, and then took a convoluted overland journey back to Georgetown.

Back from South America, Evelyn Waugh faced accusations of obscenity and blasphemy from the Catholic journal The Tablet, which objected to passages in Black Mischief.

Evelyn Waugh defended himself in an open letter to the Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Francis Bourne, which remained unpublished until 1980.

Evelyn Waugh returned to Abyssinia in August 1935 to report the opening stages of the Second Italo-Abyssinian War for the Daily Mail.

Evelyn Waugh saw little action and was not wholly serious in his role as a war correspondent.

Evelyn Waugh wrote up his Abyssinian experiences in a book, Evelyn Waugh in Abyssinia, which Rose Macaulay dismissed as a "fascist tract", on account of its pro-Italian tone.

Evelyn Waugh had known Hugh Patrick Lygon at Oxford; now he was introduced to the girls and their country house, Madresfield Court, which became the closest that he had to a home during his years of wandering.

On his conversion, Waugh had accepted that he would be unable to remarry while Evelyn Gardner was alive.

Evelyn Waugh left Piers Court on 1 September 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War and moved his young family to Pixton Park in Somerset, the Herbert family's country seat, while he sought military employment.

Evelyn Waugh never completed the novel: fragments were eventually published as Work Suspended and Other Stories.

In November 1940, Evelyn Waugh was posted to a commando unit, and, after further training, became a member of "Layforce", under Colonel Robert Laycock.

Evelyn Waugh's request was granted and, on 31 January 1944, he departed for Chagford, Devon, where he could work in seclusion.

Evelyn Waugh had little sympathy with the Communist-led Partisans and despised Tito.

Evelyn Waugh expressed those thoughts in a long report, "Church and State in Liberated Croatia".

Evelyn Waugh had been convinced of the book's qualities, "my first novel rather than my last".

Evelyn Waugh now saw little difference in morality between the war's combatants and later described it as "a sweaty tug-of-war between teams of indistinguishable louts".

Evelyn Waugh wrote up his experiences of the frustrations of postwar European travel in a novella, Scott-King's Modern Europe.

The project collapsed, but Evelyn Waugh used his time in Hollywood to visit the Forest Lawn cemetery, which provided the basis for his satire of American perspectives on death, The Loved One.

In between his journeys, Evelyn Waugh worked intermittently on Helena, a long-planned novel about the discoverer of the True Cross that was by "far the best book I have ever written or ever will write".

In 1952 Evelyn Waugh published Men at Arms, the first of his semi-autobiographical war trilogy in which he depicted many of his personal experiences and encounters from the early stages of the war.

From 1945 onwards, Evelyn Waugh became an avid collector, particularly of Victorian paintings and furniture.

Evelyn Waugh filled Piers Court with his acquisitions, often from London's Portobello Market and from house clearance sales.

Evelyn Waugh began, from 1949, to write knowledgeable reviews and articles on the subject of painting.

Evelyn Waugh was perceived as out of step with the Zeitgeist, and the large fees he demanded were no longer easily available.

Evelyn Waugh's money was running out and progress on the second book of his war trilogy, Officers and Gentlemen, had stalled.

Shortage of cash led him to agree in November 1953 to be interviewed on BBC radio, where the panel took an aggressive line: "they tried to make a fool of me, and I don't think they entirely succeeded", Evelyn Waugh wrote to Nancy Mitford.

Evelyn Waugh left the ship in Egypt and flew on to Colombo, but, he wrote to Laura, the voices followed him.

Evelyn Waugh made his own way back, now believing that he was suffering from demonic possession.

Evelyn Waugh disliked modern methods of transportation or communication, refused to drive or use the telephone, and wrote with an old-fashioned dip pen.

Evelyn Waugh expressed the views that American news reporters could not function without frequent infusions of whisky, and that every American had been divorced at least once.

Evelyn Waugh saw the pair off and wrote a wry account for The Spectator, but he was troubled by the incident and decided to sell Piers Court: "I felt it was polluted", he told Nancy Mitford.

The paper had printed an article by Spain that suggested that the sales of Evelyn Waugh's books were much lower than they were and that his worth, as a journalist, was low.

Evelyn Waugh's next major book was a biography of his longtime friend Ronald Knox, the Catholic writer and theologian who had died in August 1957.

Research and writing extended over two years during which Evelyn Waugh did little other work, delaying the third volume of his war trilogy.

Evelyn Waugh remained detached; he neither went to Cyprus nor immediately visited Auberon on the latter's return to Britain.

Evelyn Waugh was able to augment his personal finances by charging household items to the trust or selling his own possessions to it.

The interview was broadcast on 26 June 1960; according to his biographer Selina Hastings, Evelyn Waugh restrained his instinctive hostility and coolly answered the questions put to him by Freeman, assuming what she describes as a "pose of world-weary boredom".

In 1960, Evelyn Waugh was offered the honour of a CBE but declined, believing that he should have been given the superior status of a knighthood.

In 1962 Evelyn Waugh began work on his autobiography, and that same year wrote his final fiction, the long short story Basil Seal Rides Again.

Evelyn Waugh had welcomed the accession in 1958 of Pope John XXIII and wrote an appreciative tribute on the pope's death in 1963.

Evelyn Waugh described himself as "toothless, deaf, melancholic, shaky on my pins, unable to eat, full of dope, quite idle" and expressed the belief that "all fates were worse than death".

On Easter Day, 10 April 1966, after attending a Latin Mass in a neighbouring village with members of his family, Evelyn Waugh died of heart failure at his Combe Florey home, aged 62.

Evelyn Waugh never voted in elections; in 1959, he expressed a hope that the Conservatives would win the election, which they did, but would not vote for them, saying "I should feel I was morally inculpated in their follies" and added: "I do not aspire to advise my sovereign in her choice of servants".

Strictly observant, Evelyn Waugh admitted to Diana Cooper that his most difficult task was how to square the obligations of his faith with his indifference to his fellow men.

When Nancy Mitford asked him how he reconciled his often objectionable conduct with being a Christian, Evelyn Waugh replied that "were he not a Christian he would be even more horrible".

Evelyn Waugh's conservatism was aesthetic as well as political and religious.

Evelyn Waugh said that the literary world was "sinking into black disaster" and that literature might die within thirty years.

In 1945, Evelyn Waugh said that Pablo Picasso's artistic standing was the result of a "mesmeric trick" and that his paintings "could not be intelligently discussed in the terms used of the civilised masters".

Evelyn Waugh has been criticised for expressing racial and anti-semitic prejudices.

In Work Suspended and Other Stories Evelyn Waugh introduced "real" characters and a first-person narrator, signalling the literary style he would adopt in Brideshead Revisited a few years later.

Evelyn Waugh's final work of fiction, "Basil Seal Rides Again", features characters from the prewar novels; Evelyn Waugh admitted that the work was a "senile attempt to recapture the manner of my youth".

The critical reception of Vile Bodies two years later was even more enthusiastic, with Rebecca West predicting that Evelyn Waugh was "destined to be the dazzling figure of his age".

Cyril Connolly's first reaction to the book was that Evelyn Waugh's powers were failing, an opinion that he later revised.

Evelyn Waugh maintained his reputation in 1942, with Put Out More Flags, which sold well despite wartime restrictions on paper and printing.

Fellow writer Rose Macaulay believed that Evelyn Waugh's genius had been adversely affected by the intrusion of his right-wing partisan alter ego and that he had lost his detachment: "In art so naturally ironic and detached as his, this is a serious loss".

In 1959, at the request of publishers Chapman and Hall and in some deference to his critics, Evelyn Waugh revised the book and wrote in a preface: "I have modified the grosser passages but not obliterated them because they are an essential part of the book".

In 1973, Evelyn Waugh's diaries were serialised in The Observer prior to publication in book form in 1976.

Some of this picture, it was maintained by Evelyn Waugh's supporters, arose from poor editing of the diaries, and a desire to transform Evelyn Waugh from a writer to a "character".

Philip Larkin, reviewing the collection in The Guardian, thought that it demonstrated Evelyn Waugh's elitism; to receive a letter from him, it seemed, "one would have to have a nursery nickname and be a member of White's, a Roman Catholic, a high-born lady or an Old Etonian novelist".

Stannard concludes that beneath his public mask, Evelyn Waugh was "a dedicated artist and a man of earnest faith, struggling against the dryness of his soul".