1.

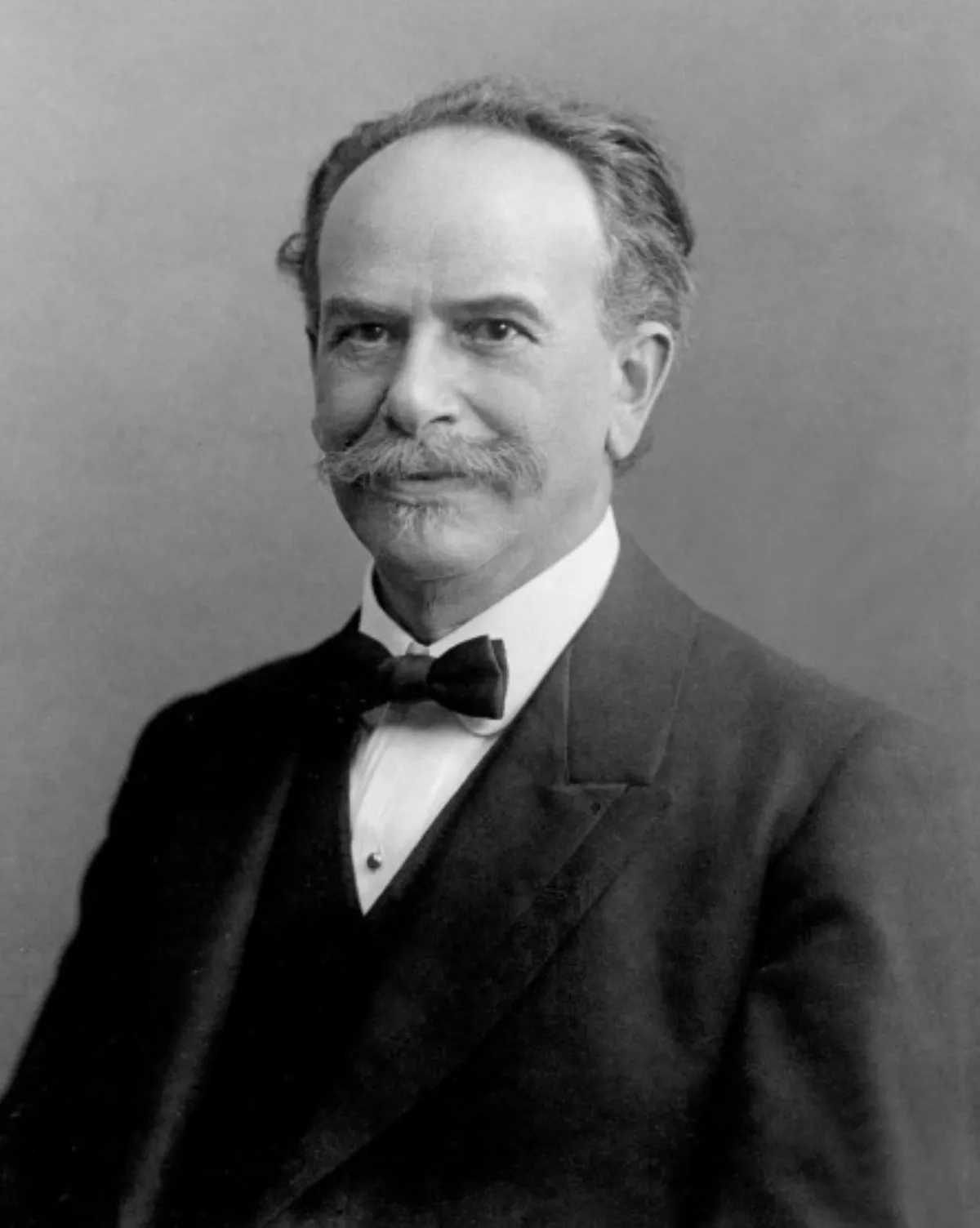

1. Franz Uri Boas was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist.

1.

1. Franz Uri Boas was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist.

Franz Boas was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology".

Franz Boas's work is associated with the movements known as historical particularism and cultural relativism.

Franz Boas then participated in a geographical expedition to northern Canada, where he became fascinated with the culture and language of the Baffin Island Inuit.

Franz Boas went on to do field work with the indigenous cultures and languages of the Pacific Northwest.

Franz Boas was one of the most prominent opponents of the then-popular ideologies of scientific racism, the idea that race is a biological concept and that human behavior is best understood through the typology of biological characteristics.

Franz Boas worked to demonstrate that differences in human behavior are not primarily determined by innate biological dispositions but are largely the result of cultural differences acquired through social learning.

Franz Boas argued that culture developed historically through the interactions of groups of people and the diffusion of ideas and that consequently there was no process towards continuously "higher" cultural forms.

Franz Boas was a proponent of the idea of cultural relativism, which holds that cultures cannot be objectively ranked as higher or lower, or better or more correct, but that all humans see the world through the lens of their own culture, and judge it according to their own culturally acquired norms.

Franz Boas was born on July 9,1858, in Minden, Westphalia, the son of Sophie Meyer and Meier Boas.

Franz Boas's parents were liberal; they did not like dogma of any kind.

Franz Boas vocally opposed and refused to convert to Christianity, but he did not identify himself as a religious Jew.

From kindergarten on, Franz Boas was educated in natural history, a subject he enjoyed.

When he started his university studies, Franz Boas first attended Heidelberg University for a semester followed by four terms at Bonn University, studying physics, geography, and mathematics at these schools.

Franz Boas completed his dissertation entitled Contributions to the Perception of the Color of Water, which examined the absorption, reflection, and polarization of light in water, and was awarded a PhD in physics in 1881.

Franz Boas had already been interested in Kantian philosophy since taking a course on aesthetics with Kuno Fischer at Heidelberg.

Franz Boas did publish six articles on psychophysics during his year of military service, but ultimately he decided to focus on geography, primarily so he could receive sponsorship for his planned Baffin Island expedition.

Franz Boas took up geography as a way to explore his growing interest in the relationship between subjective experience and the objective world.

In 1883, encouraged by Theobald Fischer, Franz Boas went to Baffin Island to conduct geographic research on the impact of the physical environment on native Inuit migrations.

The first of many ethnographic field trips, Franz Boas culled his notes to write his first monograph titled The Central Eskimo, which was published in 1888 in the 6th Annual Report from the Bureau of American Ethnology.

Franz Boas lived and worked closely with the Inuit on Baffin Island, and he developed an abiding interest in the way people lived.

Franz Boas was nonetheless forced to depend on various Inuit groups for everything from directions and food to shelter and companionship.

Franz Boas successfully searched for areas not yet surveyed and found unique ethnographic objects, but the long winter and the lonely treks across perilous terrain forced him to search his soul to find a direction for his life as a scientist and a citizen.

In 1886, Franz Boas defended his habilitation thesis, Baffin Land, and was named in geography.

Franz Boas had studied anatomy with Virchow two years earlier while preparing for the Baffin Island expedition.

Franz Boas had a chance to apply his approach to exhibits.

Franz Boas directed a team of about one hundred assistants, mandated to create anthropology and ethnology exhibits on the Indians of North America and South America that were living at the time Christopher Columbus arrived in America while searching for India.

Franz Boas traveled north to gather ethnographic material for the Exposition.

Franz Boas had intended public science in creating exhibitions for the Exposition where visitors to the Midway could learn about other cultures.

Franz Boas arranged for fourteen Kwakwaka'wakw aboriginals from British Columbia to come and reside in a mock Kwakwaka'wakw village, where they could perform their daily tasks in context.

Franz Boas had previously collaborated with Alice Cunningham Fletcher at the Bureau of American Ethnology in making several recordings of Indigenous music of North America.

Franz Boas worked there until 1894, when he was replaced by BAE archeologist William Henry Holmes.

In 1896, Franz Boas was appointed Assistant Curator of Ethnology and Somatology of the American Museum of Natural History under Putnam.

Franz Boas attempted to organize the research gathered from the Jessup Expedition into contextual, rather than evolutionary, lines.

Franz Boas's approach brought him into conflict with the President of the Museum, Morris Jesup, and its director, Hermon Bumpus.

Franz Boas resigned in 1905, never to work for a museum again.

Franz Boas observed that most scientists employ some mix of both, but in differing proportions; he considered physics a perfect example of a nomothetic science, and history, an idiographic science.

The influence of these ideas on Franz Boas is apparent in his 1887 essay, "The Study of Geography", in which he distinguished between physical science, which seeks to discover the laws governing phenomena, and historical science, which seeks a thorough understanding of phenomena on their own terms.

Franz Boas argued that geography is and must be historical in this sense.

In 1887, after his Baffin Island expedition, Franz Boas wrote "The Principles of Ethnological Classification", in which he developed this argument in application to anthropology:.

Franz Boas rejected the prevalent theories of social evolution developed by Edward Burnett Tylor, Lewis Henry Morgan, and Herbert Spencer not because he rejected the notion of "evolution" per se, but because he rejected orthogenetic notions of evolution in favor of Darwinian evolution.

Franz Boas's continuing field research led him to think of culture as a local context for human action.

Franz Boas initially broke with evolutionary theory over the issue of kinship.

Franz Boas focused on the Kwakiutl, who lived between the two clusters.

Franz Boas's children took on these names and crests as well, although his sons would lose them when they got married.

Franz Boas felt that the form an artifact took reflected the circumstances under which it was produced and used.

Franz Boas staged a funeral for the father of the boy and had the remains dissected and placed in the museum.

Franz Boas has been widely critiqued for his role in bringing the Inuit to New York and his disinterest in them once they had served their purpose at the museum.

Franz Boas was appointed a lecturer in physical anthropology at Columbia University in 1896, and promoted to professor of anthropology in 1899.

When Franz Boas left the Museum of Natural History, he negotiated with Columbia University to consolidate the various professors into one department, of which Franz Boas would take charge.

McGee's position prevailed and he was elected the organization's first president in 1902; Franz Boas was elected a vice-president, along with Putnam, Powell, and Holmes.

Franz Boas rejected this distinction between kinds of societies, and this division of labor in the academy.

Franz Boas understood all societies to have a history, and all societies to be proper objects of the anthropological society.

Historians and social theorists in the 18th and 19th centuries had speculated as to the causes of this differentiation, but Franz Boas dismissed these theories, especially the dominant theories of social evolution and cultural evolution as speculative.

Franz Boas endeavored to establish a discipline that would base its claims on a rigorous empirical study.

Franz Boas emphasized that the biological, linguistic, and cultural traits of any group of people are the product of historical developments involving both cultural and non-cultural forces.

Franz Boas established that cultural plurality is a fundamental feature of humankind and that the specific cultural environment structures much individual behavior.

Franz Boas presented himself as a role model for the citizen-scientist, who understand that even were the truth pursued as its own end, all knowledge has moral consequences.

Franz Boas found that average measures of the cranial size of immigrants were significantly different from members of these groups who were born in the United States.

Franz Boas did not deny that physical features such as height or cranial size were inherited; he did argue that the environment has an influence on these features, which is expressed through change over time.

Franz Boas looked at changes in cranial size in relation to how long the mother had been in the United States.

Since Franz Boas's times, physical anthropologists have established that the human capacity for culture is a product of human evolution.

Franz Boas was trained at a time when biologists had no understanding of genetics; Mendelian genetics became widely known only after 1900.

Franz Boas contributed greatly to the foundation of linguistics as a science in the United States.

Franz Boas published many descriptive studies of Native American languages, wrote on theoretical difficulties in classifying languages, and laid out a research program for studying the relations between language and culture which his students such as Edward Sapir, Paul Rivet, and Alfred Kroeber followed.

Franz Boas had heard similar phonetic shifts during his research in Baffin Island and in the Pacific Northwest.

Rather than take alternating sounds as objective proof of different stages in cultural evolution, Franz Boas considered them in terms of his longstanding interest in the subjective perception of objective physical phenomena.

Franz Boas considered his earlier critique of evolutionary museum displays.

Franz Boas applied these principles to his studies of Inuit languages.

Franz Boas argues an alternative explanation: that the difference is not in how Inuit pronounce the word, but rather in how English-speaking scholars perceive the pronunciation of the word.

Franz Boas understood that as people migrate from one place to another, and as the cultural context changes over time, the elements of a culture, and their meanings, will change, which led him to emphasize the importance of local histories for an analysis of cultures.

For example, his 1903 essay, "Decorative Designs of Alaskan Needlecases: A History of Conventional Designs, Based on Materials in a US Museum", provides another example of how Franz Boas made broad theoretical claims based on a detailed analysis of empirical data.

Franz Boas was an immensely influential figure throughout the development of folklore as a discipline.

Yet Franz Boas was motivated by his desire to see both anthropology and folklore become more professional and well-respected.

Franz Boas was afraid that if folklore was allowed to become its own discipline the standards for folklore scholarship would be lowered.

Franz Boas championed the use of exhaustive research, fieldwork, and strict scientific guidelines in folklore scholarship.

Franz Boas believed that a true theory could only be formed from thorough research and that even once you had a theory it should be treated as a "work in progress" unless it could be proved beyond doubt.

Franz Boas nurtured many budding folklorists during his time as a professor, and some of his students are counted among the most notable minds in folklore scholarship.

Franz Boas was passionate about the collection of folklore and believed that the similarity of folktales amongst different folk groups was due to dissemination.

Franz Boas strove to prove this theory, and his efforts produced a method for breaking a folktale into parts and then analyzing these parts.

Franz Boas fought to prove that not all cultures progressed along the same path, and that non-European cultures, in particular, were not primitive, but different.

Franz Boas remained active in the development and scholarship of folklore throughout his life.

Franz Boas became the editor of the Journal of American Folklore in 1908, regularly wrote and published articles on folklore.

Franz Boas helped to elect Louise Pound as president of the American Folklore Society in 1925.

Franz Boas was known for passionately defending what he believed to be right.

Franz Boas was especially concerned with racial inequality, which his research had indicated is not biological in origin, but rather social.

Franz Boas often emphasized his abhorrence of racism, and used his work to show that there was no scientific basis for such a bias.

Franz Boas began by remarking that "If you did accept the view that the present weakness of the American Negro, his uncontrollable emotions, his lack of energy, are racially inherent, your work would still be noble one".

Franz Boas then went on to argue against this view.

Franz Boas then went on to catalogue advances in Africa, such as smelting iron, cultivating millet, and domesticating chickens and cattle, that occurred in Africa well before they spread to Europe and Asia.

Franz Boas then described the activities of African kings, diplomats, merchants, and artists as evidence of cultural achievement.

For Franz Boas, this is just one example of the many times conquest or colonialism has brought different peoples into an unequal relation, and he mentions "the conquest of England by the Normans, the Teutonic invasion of Italy, [and] the Manchu conquest of China" as resulting in similar conditions.

Franz Boas's closing advice is that African Americans should not look to whites for approval or encouragement because people in power usually take a very long time to learn to sympathize with people out of power.

At the time, Boas had no idea that speaking at Atlanta University would put him at odds with a different prominent Black figure, Booker T Washington.

Franz Boas was critical of one nation imposing its power over others.

In 1916, Franz Boas wrote a letter to The New York Times which was published under the headline, "Why German-Americans Blame America".

When Franz Boas's letter was published, Holmes wrote to a friend complaining about "the Prussian control of anthropology in this country" and the need to end Franz Boas's "Hun regime".

Franz Boas continued to speak out against racism and for intellectual freedom.

Franz Boas helped these scientists not only to escape but to secure positions once they arrived.

Additionally, Franz Boas addressed an open letter to Paul von Hindenburg in protest against Hitlerism.

Franz Boas wrote an article in The American Mercury arguing that there were no differences between Aryans and non-Aryans and the German government should not base its policies on such a false premise.

Franz Boas trained William Jones, one of the first Native American Indian anthropologists who was killed while conducting research in the Philippines in 1909, and Albert B Lewis.

For example, Franz Boas originally defended the cephalic index as a method for describing hereditary traits, but came to reject his earlier research after further study; he similarly came to criticize his own early work in Kwakiutl language and mythology.