1.

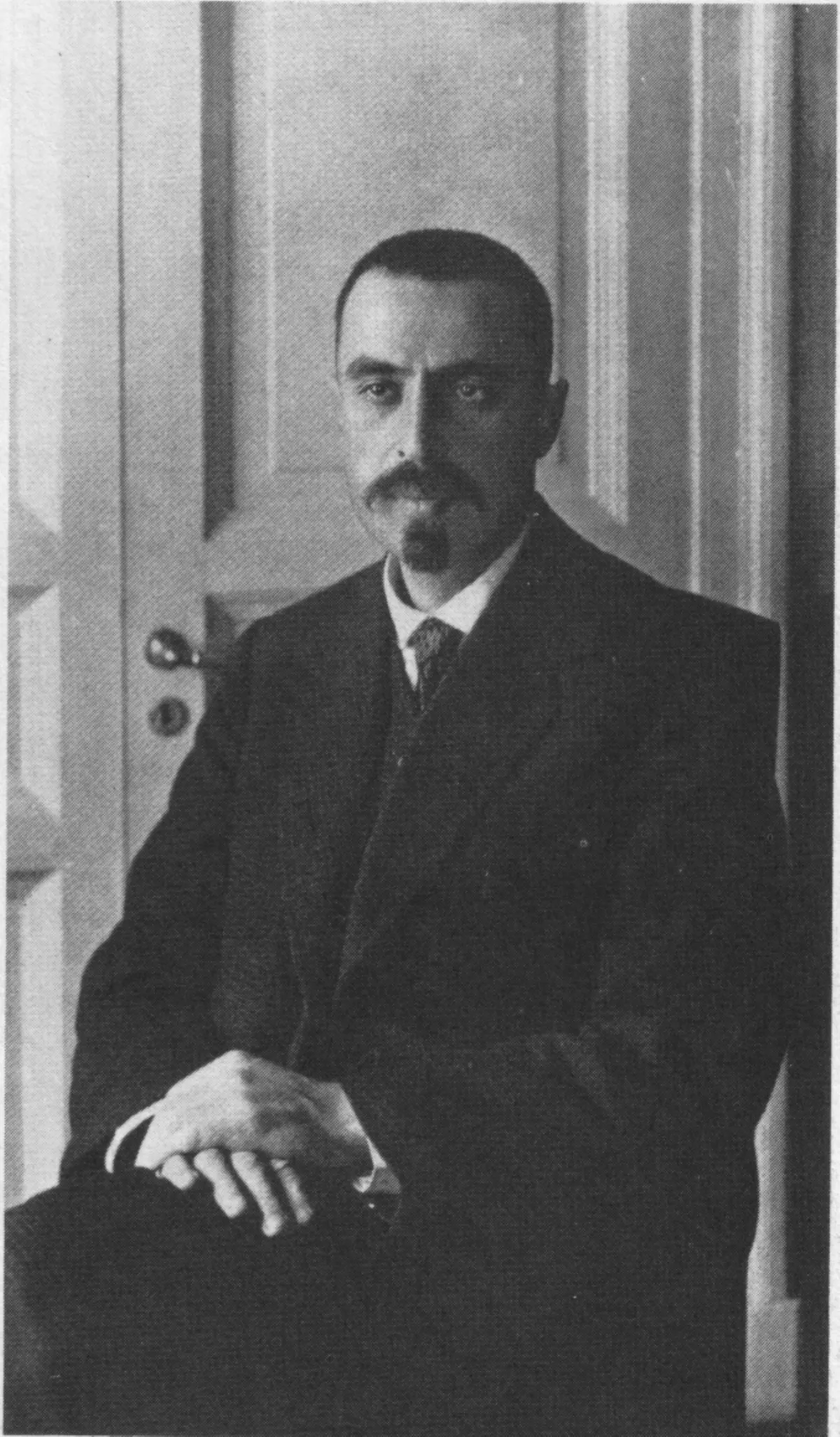

1. Shortly after entering the Duma, Irakli Tsereteli was arrested and charged with conspiracy to overthrow the Tsarist government, and exiled to Siberia.

1.

1. Shortly after entering the Duma, Irakli Tsereteli was arrested and charged with conspiracy to overthrow the Tsarist government, and exiled to Siberia.

In 1915, during his Siberian exile, Irakli Tsereteli formed what would become known as Siberian Zimmerwaldism, which advocated for the role of the Second International in ending the war.

Irakli Tsereteli developed the idea of "Revolutionary Defensism", the concept of a defensive war which only allowed for the defence of territory, and argued it was not being utilized.

Concerned that political fragmentation would lead to a civil war in Russia, Irakli Tsereteli strived to broker compromises between the various leftist factions in the Russian Revolution and was the force behind efforts to work together with the middle classes, to no avail.

Irakli Tsereteli worked as a diplomat at the Paris Peace Conference, where he lobbied for international recognition and assistance for the newly independent Democratic Republic of Georgia; meaningful assistance largely failed to materialize before the Bolshevik-led Red Army invaded in 1921.

An avowed internationalist, Irakli Tsereteli grew increasingly distant from the Georgian Mensheviks who gradually adopted more nationalist tendencies.

Irakli Tsereteli spent the rest of his life in exile, mainly in France, working with socialist organisations and writing on socialism, and died in New York City in 1959.

Irakli Tsereteli had one sister, Eliko and brother, Levan.

Irakli Tsereteli grew up in nearby Kutaisi and spent the summers at his family's estate in Gorisa; from a young age he noticed the inequality between his family and their servants and the local peasants, and desired to fix the imbalance.

When he was three, Irakli Tsereteli's mother died, so he and his siblings were sent to live with two aunts in Kutaisi, while Giorgi moved to Tiflis, the administrative centre of the Caucasus, occasionally visiting the children.

At the gymnasium Irakli Tsereteli distanced himself from Christianity, questioning death and its meaning, and was introduced to the writings of the British naturalist and biologist Charles Darwin, which factored into his move away from religion.

Irakli Tsereteli completed his schooling in 1900, the same year as his father's death, and moved to Moscow to study law.

Irakli Tsereteli was arrested in the spring of 1901 and after a brief detention was allowed to return to Georgia.

At a meeting of student protesters on 9 February 1902 Irakli Tsereteli was arrested; considered one of the most radical leaders, he was one of two students given a sentence of five years' exile in Siberia, the longest sentence given to the protesting students.

On his release from exile Irakli Tsereteli returned to Georgia and aligned himself with the RSDLP's Georgian branch, later known as the Georgian Mensheviks, the minority faction within the party.

Irakli Tsereteli began working as an editor for his father's former publication, Kvali, writing most of their leading articles.

Irakli Tsereteli was allowed to leave Georgia, likely due to the influence of his uncle, and he moved to Berlin to resume his law studies, spending 18 months in Europe.

Irakli Tsereteli remained in Georgia throughout the summer of 1906 recovering from his illness, and was not politically active.

Irakli Tsereteli strived to unite the opposition parties, though he faced considerable opposition both from the Kadets, a liberal group who had previously opposed the government but were now more amicable to them, and the Bolsheviks, the larger faction within the RSDLP, who worked to discredit the Mensheviks in the Duma.

Irakli Tsereteli sought out an alliance with the other leftist factions, namely the Socialist Revolutionary Party and the Trudoviks, a splinter group from the Socialist Revolutionaries.

On occasion Irakli Tsereteli was able to visit Irkutsk, engaging in political talks.

However, much like the rest of the population in the region he regularly read updates in the newspapers, and tried to ascertain what type of opposition to the war was occurring internationally; though most mentions of opposition movements was censored, Irakli Tsereteli concluded that something had to exist, and felt that the Second International, a Paris-based organization of socialist and labour parties, could play some role in ending the war.

Irakli Tsereteli engaged in discussion with other Social Democrats in the Irkutsk region on his views towards the war; they would all publish their thoughts in journals, Irakli Tsereteli including his ideas in a journal that he edited, Siberian Journal, later replaced by the Siberian Review.

Irakli Tsereteli agreed with the majority Internationalist view, which had stated that the war was not totally inevitable, and that the International had thus been trying to limit the threat of war.

Irakli Tsereteli further argued that the International was not strong enough to call a general strike, as the proletariat was too weak to overthrow capitalism, and it would only hurt the movement.

Irakli Tsereteli stated that all of the warring states were guilty and none could be victorious.

Irakli Tsereteli called the conflict an "imperialist struggle over spheres of influence", largely conforming to the view of the International, though stating his support for the idea of self-defence.

Publication of more articles was halted by the authorities, but the articles Irakli Tsereteli did write had a considerable impact, and helped keep him relevant even while in exile.

News of the February Revolution, the mass protests that led to the overthrow of the Tsar and ended the Russian Empire, began on 23 February 1917; news of it first arrived in Irkutsk on 2 March and reached Usolye that evening; Irakli Tsereteli left for Irkutsk the following morning.

Several people, including Irakli Tsereteli, arrested the regional governor and declared Irkutsk a free city.

Irakli Tsereteli took a leading role in this committee, though the work took a considerable toll on his health and after ten days he stepped down as he began to vomit blood.

Irakli Tsereteli was the first of the major exiled politicians to arrive in Petrograd after the revolution, and thus was welcomed by a large crowd at the train station.

Immediately, Irakli Tsereteli went to the Petrograd Soviet and gave a speech in support of the revolution, but warned members that it was too early to implement socialist policies.

Irakli Tsereteli stated that both the country and the revolution had to be defended from the German Empire, but that the Soviet should pressure the Provisional Government to negotiate a peace, one that recognized self-determination and did not include annexation.

Irakli Tsereteli led the Soviet side in negotiations with the Provisional Government to have the no-annexation policy adopted, in the process showing that he had effectively become a leader within the Soviet.

Irakli Tsereteli was not seeking an increased role for himself, nor did he want the Soviet to become a power-base, but simply a representative body of the workers and soldiers.

Irakli Tsereteli was given the position of Minister of Post and Telegraph, an office created just so he could be in the cabinet.

Reluctant to join the government, Irakli Tsereteli only did so in hopes of avoiding the dissolution of the Provisional Government and the outbreak of civil war.

Irakli Tsereteli did little in his role as minister, which he held until August 1917, and kept his focus on the Soviet, leaving the actual administration to others.

Irakli Tsereteli realized that, as a member of the cabinet, he could "exercise real influence upon the government, since the government and the middle classes which back it are greatly impressed by the power of the Soviet".

Irakli Tsereteli had travelled to Kiev with a party representing the Provisional Government to negotiate a means to ensure defence of Russia while respecting Ukrainian self-determination.

Irakli Tsereteli was appointed Minister of the Interior, serving for two weeks until a new cabinet could be formed.

However, with Kerensky frequently absent, Irakli Tsereteli served as the de facto Prime Minister, and tried to implement some domestic reforms and restore order throughout the country.

Roobol believed that Irakli Tsereteli only left because he was confident that the new Kerensky government was secure enough to last until the Constituent Assembly could meet.

Irakli Tsereteli defied the authorities and stayed in Petrograd for the only meeting of the Constituent Assembly, which took place on 5 January 1918.

Back in Georgia, Irakli Tsereteli delivered a speech on 23 February 1918 at the Transcaucasian Centre of Soviets, reporting on the events in Russia.

Irakli Tsereteli warned the delegates of the problems dual power had caused, and that the soviet would have to surrender its power to a legislative body.

Irakli Tsereteli strongly denounced the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which was signed between the Bolshevik government and the Central Powers to end Russia's involvement in the war, as it would have meant ceding important Transcaucasian territories to the Ottoman, such as the Black Sea port city of Batumi.

That he supported what was essentially a nationalist state contradicted his earlier internationalist stance, though Roobol suggested that Irakli Tsereteli "wanted a state which would be more than a Georgian national state", and championed the causes of the ethnic minorities within Georgia.

Irakli Tsereteli proved instrumental in helping Karl Kautsky, a leading Marxist theoretician, arrive in Georgia in August 1920 to research a book on the country.

Irakli Tsereteli was recovering in France when he heard about the Red Army invasion of Georgia and subsequent Bolshevik takeover in February 1921.

Irakli Tsereteli helped edit fellow Menshevik Pavel Axelrod's works after the latter's death in 1928.

Highly indignant about what he called the "platonic attitute" of the Western socialist parties towards Georgia and their inadequate support to the beleaguered country, Irakli Tsereteli continued to regard Bolshevism as the cause of the troubles, but believed that the Bolshevik regime would not survive long.

Irakli Tsereteli continued to attend International's conferences in Europe, trying to get the organization to adopt a stronger anti-Bolshevik stance, though with limited success.

Irakli Tsereteli gradually distanced himself from his fellow Georgian exiles, and opposed both the liberal nationalist Zurab Avalishvili and the social democrat Noe Zhordania; all three wrote extensively abroad on Georgian politics.

Irakli Tsereteli accepted the principle of the fight for Georgia's independence, but rejected the view of Zhordania and other Georgian emigres that the Bolshevik domination was effectively identical to Russian domination.

Irakli Tsereteli felt that if the population of the Russian Empire were united, and not divided along ethnic or national lines, socialist policies could be implemented.

Irakli Tsereteli's views were heavily influenced by the writings of Pavel Axelrod, whom Tsereteli considered his most important teacher.

Irakli Tsereteli never deviated from his internationalist stance, which eventually led to conflict with other Georgian Mensheviks, who became far more nationalist throughout the 1920s.

Siberian Zimmerwaldism allowed for, under certain circumstances, a defensive war, though Irakli Tsereteli argued that only Belgium fitted these criteria, as the other warring states were fighting offensively.

Irakli Tsereteli's leading role in the Petrograd Soviet led Lenin to refer to Tsereteli as "the conscience of the Revolution".

Irakli Tsereteli quickly faded from prominence in histories of the era.

Rex A Wade, one of the preeminent historians of the Russian Revolution, noted that Tsereteli "was not as flamboyant as Kerensky or as well known to foreigners as Miliukov, and therefore has not attracted as much attention as either in Western writings".