1.

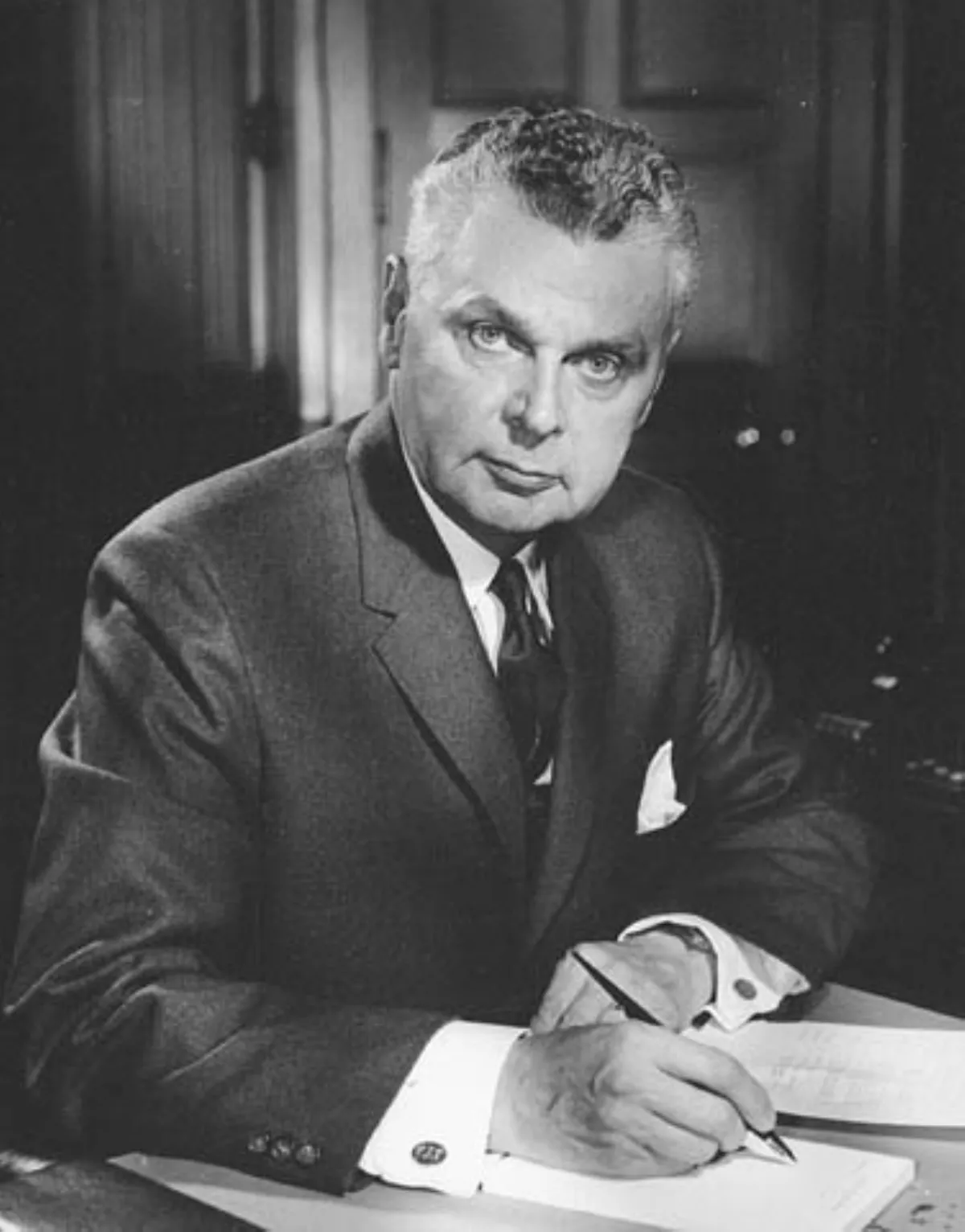

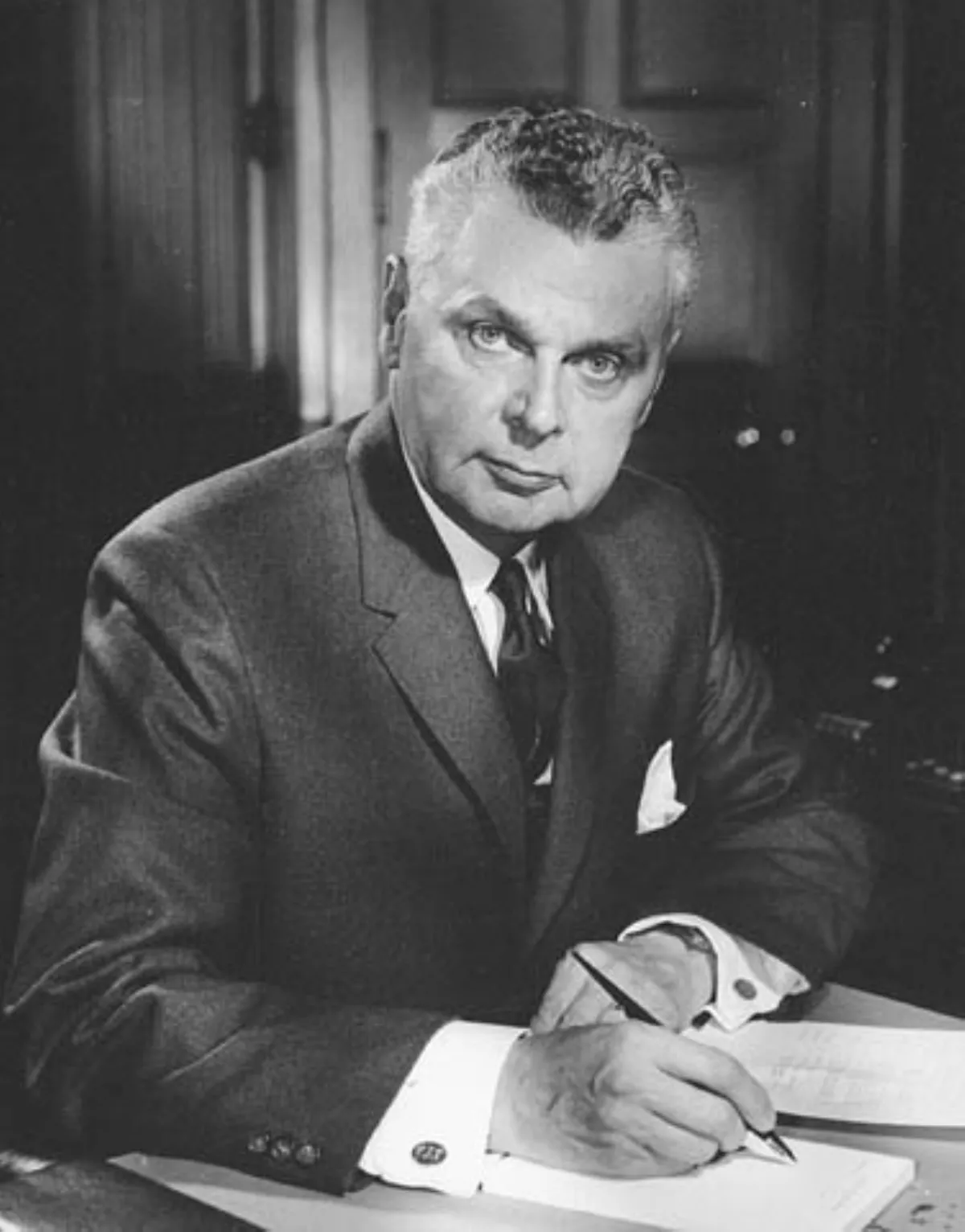

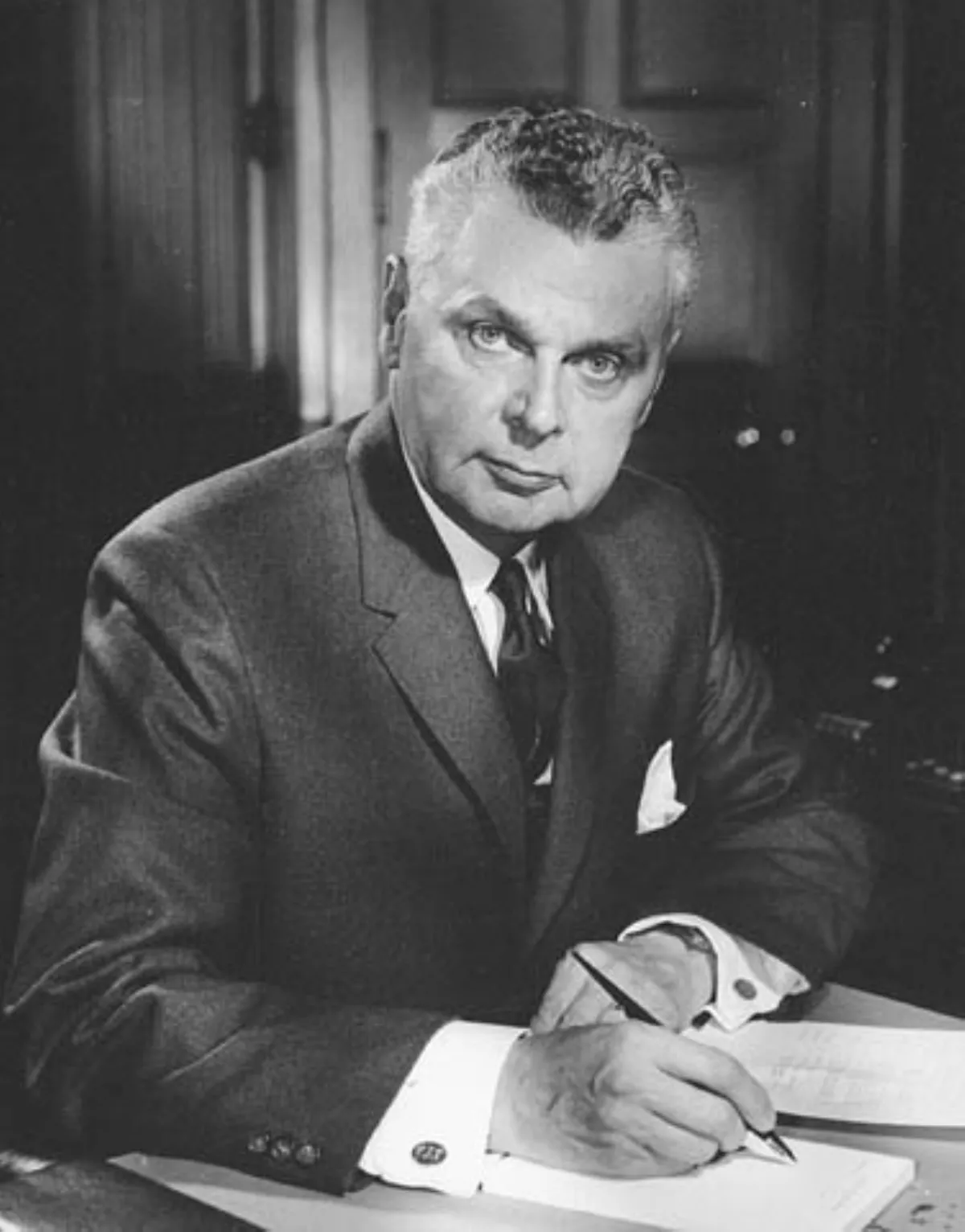

1. John Diefenbaker was the only Progressive Conservative party leader between 1930 and 1979 to lead the party to an election victory, doing so three times, although only once with a majority of the seats in the House of Commons.

1.

1. John Diefenbaker was the only Progressive Conservative party leader between 1930 and 1979 to lead the party to an election victory, doing so three times, although only once with a majority of the seats in the House of Commons.

John Diefenbaker grew up in the province and was interested in politics from a young age.

John Diefenbaker contested elections through the 1920s and 1930s with little success until he was finally elected to the House of Commons in 1940.

John Diefenbaker gained that position in 1956, on his third attempt.

John Diefenbaker appointed the first female minister in Canadian history to his cabinet, as well as the first Indigenous member of the Senate.

In 1962, John Diefenbaker's government eliminated racial discrimination in immigration policy.

John Diefenbaker is remembered for his role in the 1959 cancellation of the Avro Arrow project.

John Diefenbaker stayed on as party leader, becoming Opposition leader, but his second loss at the polls prompted opponents within the party to force him to a leadership convention in 1967.

John Diefenbaker stood for re-election as party leader at the last moment, but attracted only minimal support and withdrew.

John Diefenbaker remained in parliament until his death in 1979, two months after Joe Clark became the first Progressive Conservative prime minister since Diefenbaker.

John Diefenbaker's father was the son of German immigrants from Adersbach in Baden; Mary Diefenbaker was of Scottish descent and Diefenbaker was Baptist.

William John Diefenbaker was a teacher, and had deep interests in history and politics, which he sought to inculcate in his students.

John Diefenbaker had remarkable success doing so; of the 28 students at his school near Toronto in 1903, four, including his son, John, served as Conservative MPs in the 19th Canadian Parliament beginning in 1940.

The John Diefenbaker family moved west in 1903, for William John Diefenbaker to accept a position near Fort Carlton, then in the Northwest Territories.

In February 1910, the John Diefenbaker family moved to Saskatoon, the site of the University of Saskatchewan.

John Diefenbaker had been interested in politics from an early age and told his mother at the age of eight or nine that he would some day be prime minister.

John Diefenbaker told him that it was an impossible ambition, especially for a boy living on the prairies.

John Diefenbaker claimed that his first contact with politics came in 1910, when he sold a newspaper to Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, in Saskatoon to lay the cornerstone for the university's first building.

John Diefenbaker received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1915, and his Master of Arts the following year.

John Diefenbaker was commissioned a lieutenant into the 196th Battalion, CEF, in May 1916.

John Diefenbaker related in his memoirs that he was hit by a shovel, and the injury eventually resulted in him being sent home as an invalid.

John Diefenbaker's recollections do not correspond with his army medical records, which show no contemporary account of such an injury, and his biographer, Denis Smith, speculates that any injury was psychosomatic.

John Diefenbaker received his law degree in 1919, the first student to secure three degrees from the University of Saskatchewan.

The local people were mostly immigrants, and John Diefenbaker's research found them to be particularly litigious.

John Diefenbaker won the local people over through his success; in his first year in practice, he tried 62 jury trials, winning approximately half of his cases.

John Diefenbaker rarely called defence witnesses, thereby avoiding the possibility of rebuttal witnesses for the Crown, and securing the last word for himself.

John Diefenbaker then courted Beth Newell, a cashier in Saskatoon, and by 1922, the two were engaged.

However, in 1923, Newell was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and John Diefenbaker broke off contact with her.

On May 1,1924, John Diefenbaker moved to Prince Albert, leaving a law partner in charge of the Wakaw office.

John Diefenbaker was fond of stating, in his later years, that the only protection a Conservative had in the province was that afforded by the game laws.

Diefenbaker's father, William, was a Liberal; however, John Diefenbaker found himself attracted to the Conservative Party.

Free trade was widely popular throughout Western Canada, but John Diefenbaker was convinced by the Conservative position that free trade would make Canada an economic dependent of the United States.

John Diefenbaker recalled in his memoirs that, in 1921, he had been elected as secretary of the Wakaw Liberal Association while absent in Saskatoon, and had returned to find the association's records in his office.

Journalist Peter C Newman, in his best-selling account of the Diefenbaker years, suggested that this choice was made for practical, rather than political reasons, as Diefenbaker had little chance of defeating established politicians and securing the Liberal nomination for either the House of Commons or the Legislative Assembly.

John Diefenbaker, who had been confirmed as Conservative candidate, stood against King in the 1926 election, a rare direct electoral contest between two individuals who had or would become prime minister.

John Diefenbaker stood for the Legislative Assembly in the 1929 provincial election.

John Diefenbaker was defeated, but Saskatchewan Conservatives formed their first government, with help from smaller parties.

John Diefenbaker chose not to stand for the House of Commons in the 1930 federal election, citing health reasons.

John Diefenbaker continued a high-profile legal practice, and in 1933, ran for mayor of Prince Albert.

John Diefenbaker was defeated by 48 votes in an election in which over 2,000 ballots were cast.

In 1934, when the Crown prosecutor for Prince Albert resigned to become the Conservative Party's legislative candidate, John Diefenbaker took his place as prosecutor.

John Diefenbaker did not stand in the 1934 provincial election, in which the governing Conservatives lost every seat.

Six days after the election, John Diefenbaker resigned as Crown prosecutor.

The other ten candidates withdrew, and John Diefenbaker won the position by default.

John Diefenbaker asked the federal party for $10,000 in financial support, but the funds were refused, and the Conservatives were shut out of the legislature in the 1938 provincial elections for the second consecutive time.

John Diefenbaker himself was defeated in the Arm River riding by 190 votes.

John Diefenbaker continued to run the provincial party out of his law office and paid the party's debts from his own pocket.

John Diefenbaker campaigned aggressively in Lake Centre, holding 63 rallies and seeking to appeal to members of all parties.

John Diefenbaker joined a shrunken and demoralized Conservative caucus in the House of Commons.

John Diefenbaker was appointed to the House Committee on the Defence of Canada Regulations, an all-party committee which examined the wartime rules which allowed arrest and detention without trial.

On June 13,1940, John Diefenbaker made his maiden speech in the House of Commons, supporting the regulations, and emphatically stating that most Canadians of German descent were loyal.

However, John Diefenbaker proved a gadfly and an annoyance to Mackenzie King.

John Diefenbaker remained as leader for several months, although he could not enter the chamber of the House of Commons.

John Diefenbaker objected to what he saw as an attempt to rig the party's choice of new leader and stood for the leadership himself at the party's 1942 leadership convention.

Bracken was elected on the second ballot; John Diefenbaker finished a distant third in both polls.

John Diefenbaker staked out a position on the populist left of the PC party.

John Diefenbaker objected to the great powers used by the Mackenzie King government to attempt to root out Soviet spies after the war, such as imprisonment without trial, and complained about the government's proclivity for letting its wartime powers become permanent.

When Bracken resigned on July 17,1948, John Diefenbaker announced his candidacy.

John Diefenbaker stated in his memoirs that he had considered retiring from the House; with Drew only a year older than he was, the Westerner saw little prospect of advancement and had received tempting offers from Ontario law firms.

John Diefenbaker's party had taken Prince Albert only once, in 1911, but he decided to stand in that riding for the 1953 election and was successful.

John Diefenbaker would hold that seat for the rest of his life.

John Diefenbaker paid $1,500 and sat a token bar examination to join the Law Society of British Columbia to take the case, and gained an acquittal, prejudicing the jury against the Crown prosecutor and pointing out a previous case in which interference had caused information to be lost in transmission.

John Diefenbaker later fell ill from leukemia and died in 1951.

In 1953, John Diefenbaker married Olive Palmer, whom he had courted while living in Wakaw.

Olive John Diefenbaker became a great source of strength to her husband.

John Diefenbaker won Prince Albert in 1953, even as the Tories suffered a second consecutive disastrous defeat under Drew.

However, John Diefenbaker was never a member of the "Five O'clock Club" of Drew intimates who met the leader in his office for a drink and gossip each day.

John Diefenbaker played a relatively minor role in the Pipeline Debate, speaking only once.

The only serious competition to John Diefenbaker came from Donald Fleming, who had finished third at the previous leadership convention, but his having repeatedly criticised Drew's leadership ensured that the critical Ontario delegates would not back Fleming, all but destroying his chances of victory.

At the leadership convention in Ottawa in December 1956, John Diefenbaker won on the first ballot, and the dissidents reconciled themselves to his victory.

In January 1957, John Diefenbaker took his place as Leader of the Official Opposition.

John Diefenbaker ran on a platform which concentrated on changes in domestic policies.

John Diefenbaker pledged to work with the provinces to reform the Senate.

John Diefenbaker proposed a vigorous new agricultural policy, seeking to stabilize income for farmers.

John Diefenbaker sought to reduce dependence on trade with the United States, and to seek closer ties with the United Kingdom.

When John Diefenbaker took office as Prime Minister of Canada on June 21,1957, only one Progressive Conservative MP, Earl Rowe, had served in federal governmental office, for a brief period under Bennett in 1935.

John Diefenbaker appointed Ellen Fairclough as Secretary of State for Canada, the first woman to be appointed to a Cabinet post, and Michael Starr as Minister of Labour, the first Canadian of Ukrainian descent to serve in Cabinet.

John Diefenbaker spoke for two hours and three minutes, and devastated his Liberal opposition.

John Diefenbaker mocked Pearson, contrasting the party leader's address at the Liberal leadership convention with his speech to the House:.

John Diefenbaker read from an internal report provided to the St Laurent government in early 1957, warning that a recession was coming, and stated:.

Massey agreed to the dissolution, and John Diefenbaker set an election date of March 31,1958.

The Liberal Party leader tried to make an issue of the fact that John Diefenbaker had called a winter election, generally disfavoured in Canada due to travel difficulties.

John Diefenbaker had appointed the first First Nations member of the Senate, James Gladstone, in January 1958, and in 1960, his government extended voting rights to all native people.

In 1962, John Diefenbaker's government eliminated race discrimination clauses in immigration laws.

John Diefenbaker pursued a "One Canada" policy, seeking equality of all Canadians.

John Diefenbaker did recommend the appointment of the first French-Canadian governor general, Georges Vanier.

Negotiations between Minister of Finance Fleming and Coyne for the latter's resignation broke down, with the governor making the dispute public, and John Diefenbaker sought to dismiss Coyne by legislation.

John Diefenbaker was able to get legislation to dismiss Coyne through the House, but the Liberal-controlled Senate invited Coyne to testify before one of its committees.

John Diefenbaker attended a meeting of the Commonwealth Prime Ministers in London shortly after taking office in 1957.

John Diefenbaker believed that the mother country should place the Commonwealth first, and sought to discourage Britain's entry.

John Diefenbaker privately expressed his distaste for apartheid to South African External Affairs Minister Eric Louw and urged him to give the black and coloured people of South Africa at least the minimal representation they had originally had.

The prime ministers were divided; John Diefenbaker broke the deadlock by proposing that South Africa only be re-admitted if it joined other states in condemning apartheid in principle.

When Eisenhower addressed Parliament in October 1958, he downplayed trade concerns that John Diefenbaker had publicly expressed.

John Diefenbaker had approved plans to join the United States in what became known as NORAD, an integrated air defence system, in mid-1957.

In 1959, the John Diefenbaker government cancelled the development and manufacture of the Avro CF-105 Arrow.

In September 1958, John Diefenbaker warned that the Arrow would come under complete review in six months.

John Diefenbaker began seeking out other projects including a US-funded "saucer" program that became the VZ-9 Avrocar, and mounted a public relations offensive urging that the Arrow go into full production.

Kennedy did not respond until Canadian officials asked what had become of John Diefenbaker's note, two weeks later.

In January 1961, John Diefenbaker visited Washington to sign the Columbia River Treaty.

Kennedy and John Diefenbaker started off well, but matters soon worsened.

John Diefenbaker was annoyed by Kennedy's speech to Parliament, in which he urged Canada to join the OAS, and by the President spending most of his time talking to Leader of the Opposition Pearson at the formal dinner.

John Diefenbaker was initially inclined to go along with Kennedy's request that nuclear weapons be stationed on Canadian soil as part of NORAD.

However, when an August 3,1961 letter from Kennedy which urged this was leaked to the media, John Diefenbaker was angered and withdrew his support.

John Diefenbaker was upset at both the lack of consultation and the fact that he was given less than two hours advance word.

John Diefenbaker was angered again when the US government released a statement stating that it had Canada's full support.

Harkness and the Chiefs of Staff had Canadian forces clandestinely go to that alert status anyway, and John Diefenbaker eventually authorized it.

Newspapers across Canada criticized John Diefenbaker, who was convinced the statement was part of a plot by Kennedy to bring down his government.

John Diefenbaker continued to try to avoid taking a firm position.

The bitter divisions within the Cabinet continued, with John Diefenbaker deliberating whether to call an election on the issue of American interference in Canadian politics.

John Diefenbaker asked ministers supporting him to stand, and when only about half did, stated that he was going to see the Governor General to resign, and that Fleming would be the next Prime Minister.

Green called his Cabinet colleagues a "nest of traitors," but eventually cooler heads prevailed, and John Diefenbaker was urged to return and to fight the motion of non-confidence scheduled for the following day.

Peter Stursberg, who wrote two books about the John Diefenbaker years, stated of that campaign:.

John Diefenbaker held to power for several days, until six Quebec Social Credit MPs signed a statement that Pearson should form the government.

John Diefenbaker continued to lead the Progressive Conservatives, again as Leader of the Opposition.

John Diefenbaker preferred the existing Canadian Red Ensign or another design showing symbols of the nation's heritage.

John Diefenbaker dismissed the adopted design, with a single red maple leaf and two red bars, as "a flag that Peruvians might salute", a reference to Peru's red-white-red tricolour.

At the request of Quebec Tory Leon Balcer, who feared devastating PC losses in the province at the next election, Pearson imposed closure, and the bill passed with the majority singing "O Canada" as John Diefenbaker led the dissenters in "God Save the Queen".

In what John Diefenbaker saw as a partisan attack, Pearson established a one-man Royal Commission, which, according to John Diefenbaker biographer Smith, indulged in "three months of reckless political inquisition".

John Diefenbaker initially beat back attempts to remove him without trouble.

When Pearson called an election in 1965 in the expectation of receiving a majority, John Diefenbaker ran an aggressive campaign.

John Diefenbaker initially made no announcement as to whether he would stand, but angered by a resolution at the party's policy conference which spoke of "deux nations" or "two founding peoples", decided to seek to retain his leadership.

John Diefenbaker was embittered by his loss of the party leadership.

Pearson announced his retirement in December 1967, and John Diefenbaker forged a wary relationship of mutual respect with Pearson's successor, Pierre Trudeau.

Trudeau called a general election for June 1968; Stanfield asked John Diefenbaker to join him at a rally in Saskatoon, which John Diefenbaker refused, although the two appeared at hastily arranged photo opportunities.

The division in the party broke out in well-publicised dissensions, as when John Diefenbaker called on Progressive Conservative MPs to break with Stanfield's position on the Official Languages bill, and nearly half the caucus voted against their leader's will or abstained.

Pearson died of cancer in 1972, and John Diefenbaker was asked if he had kind words for his old rival.

John Diefenbaker was re-elected comfortably in his home riding, and the Progressive Conservatives came within two seats of matching the Liberal total.

John Diefenbaker was relieved both that Trudeau had been humbled and that Stanfield had been denied power.

Joe Clark succeeded Stanfield as party leader in 1976, but as Clark had supported the leadership review, John Diefenbaker held a grudge against him.

John Diefenbaker had supported Claude Wagner for leader, but when Clark won, stated that Clark would make "a remarkable leader of this party".

Clark had defeated Trudeau, though only gaining a minority government, and John Diefenbaker returned to Ottawa to witness the swearing-in, still unreconciled to his old opponents among Clark's ministers.

Two months later, John Diefenbaker died of a heart attack in his study at age 83.

John Diefenbaker had extensively planned his funeral in consultation with government officials.

John Diefenbaker lay in state in the Hall of Honour in Parliament for two and a half days; 10,000 Canadians passed by his casket.

John Diefenbaker's coffin was accompanied by that of his wife Olive, disinterred from temporary burial in Ottawa.

Some of John Diefenbaker's policies did not survive the 16 years of Liberal government that followed his fall.

John Diefenbaker's administration was not an aberration from which Canada will recover under the sensible rule of the established classes.

John Diefenbaker received several honorary degrees in recognition of his political career:.