1.

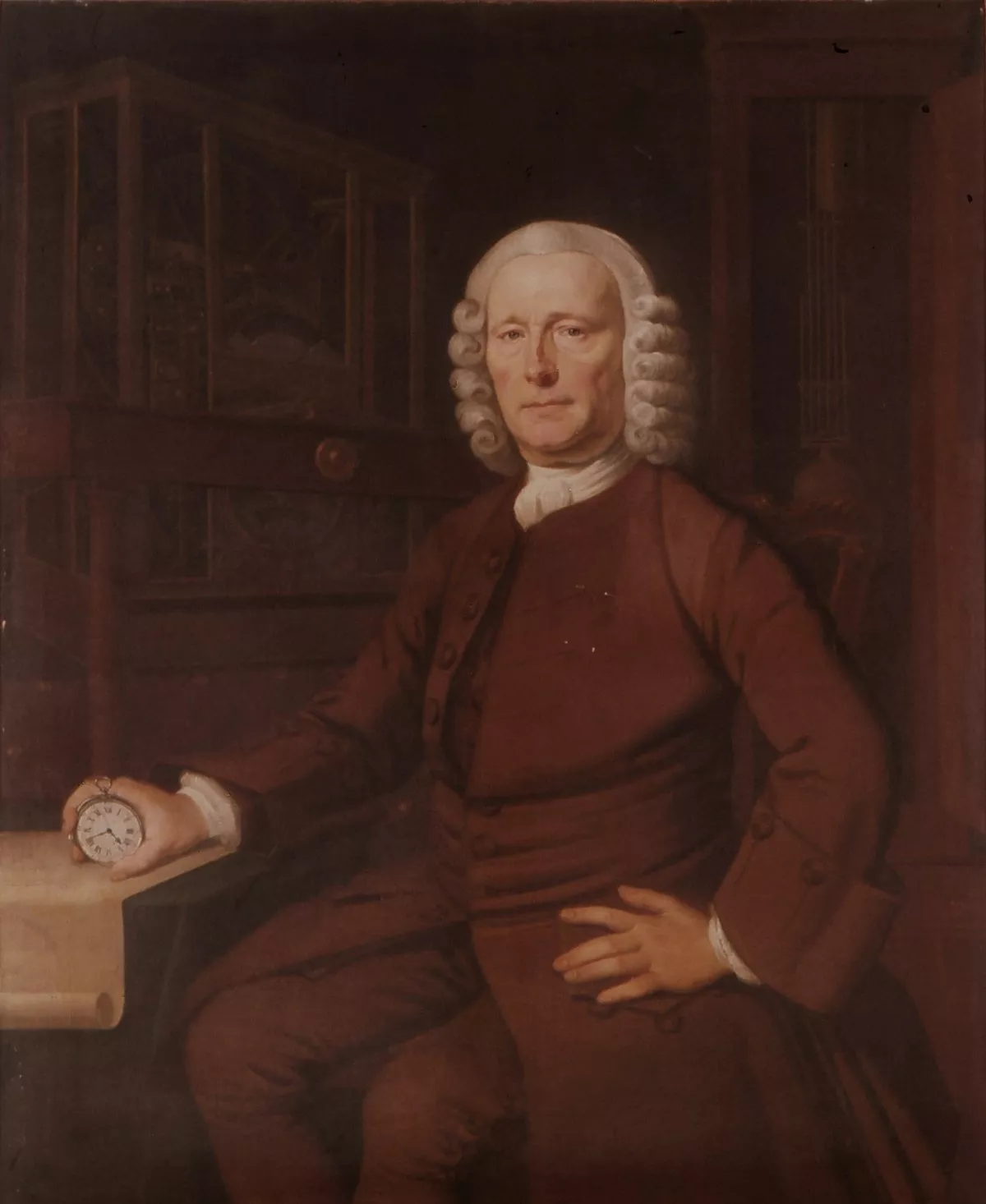

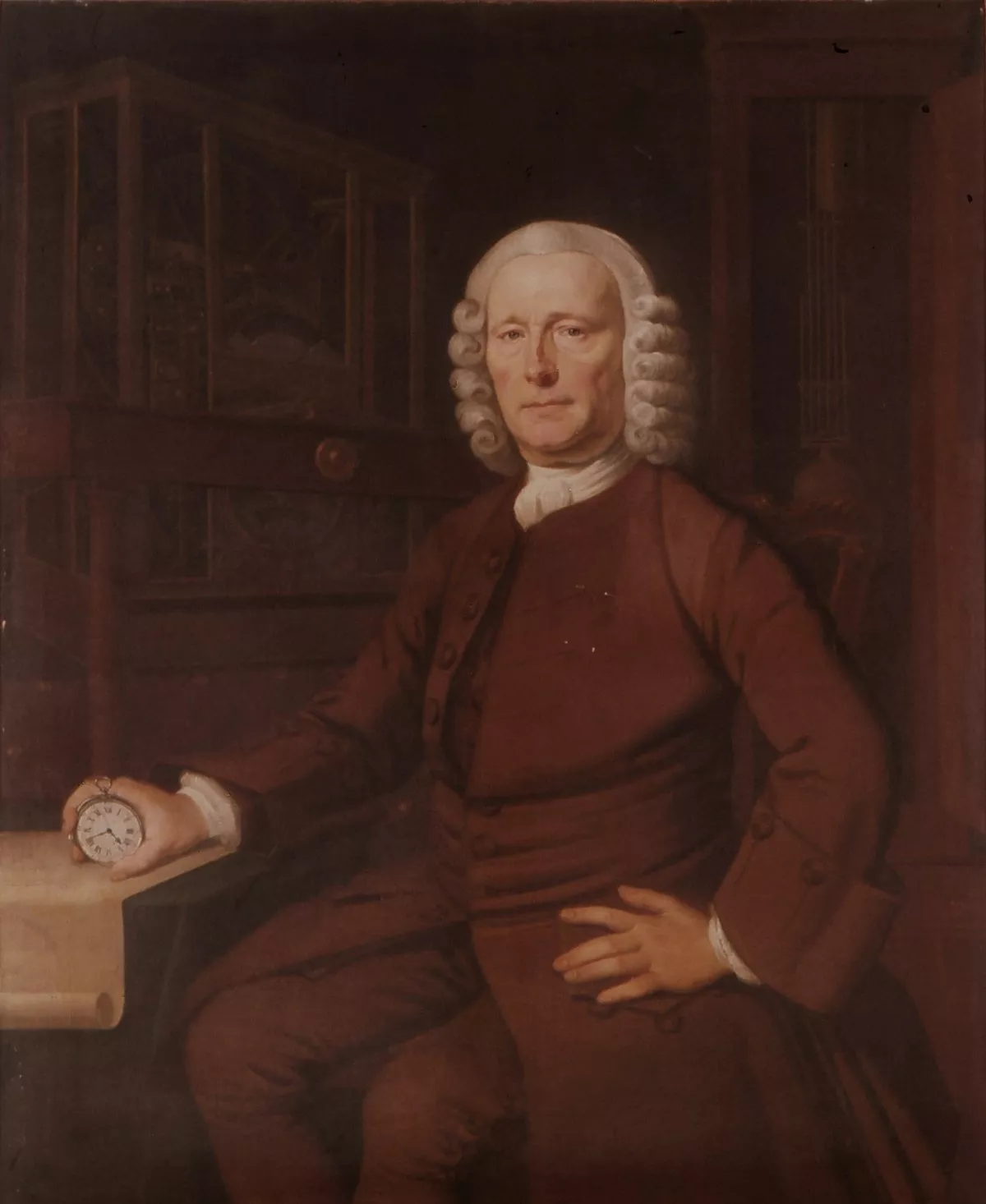

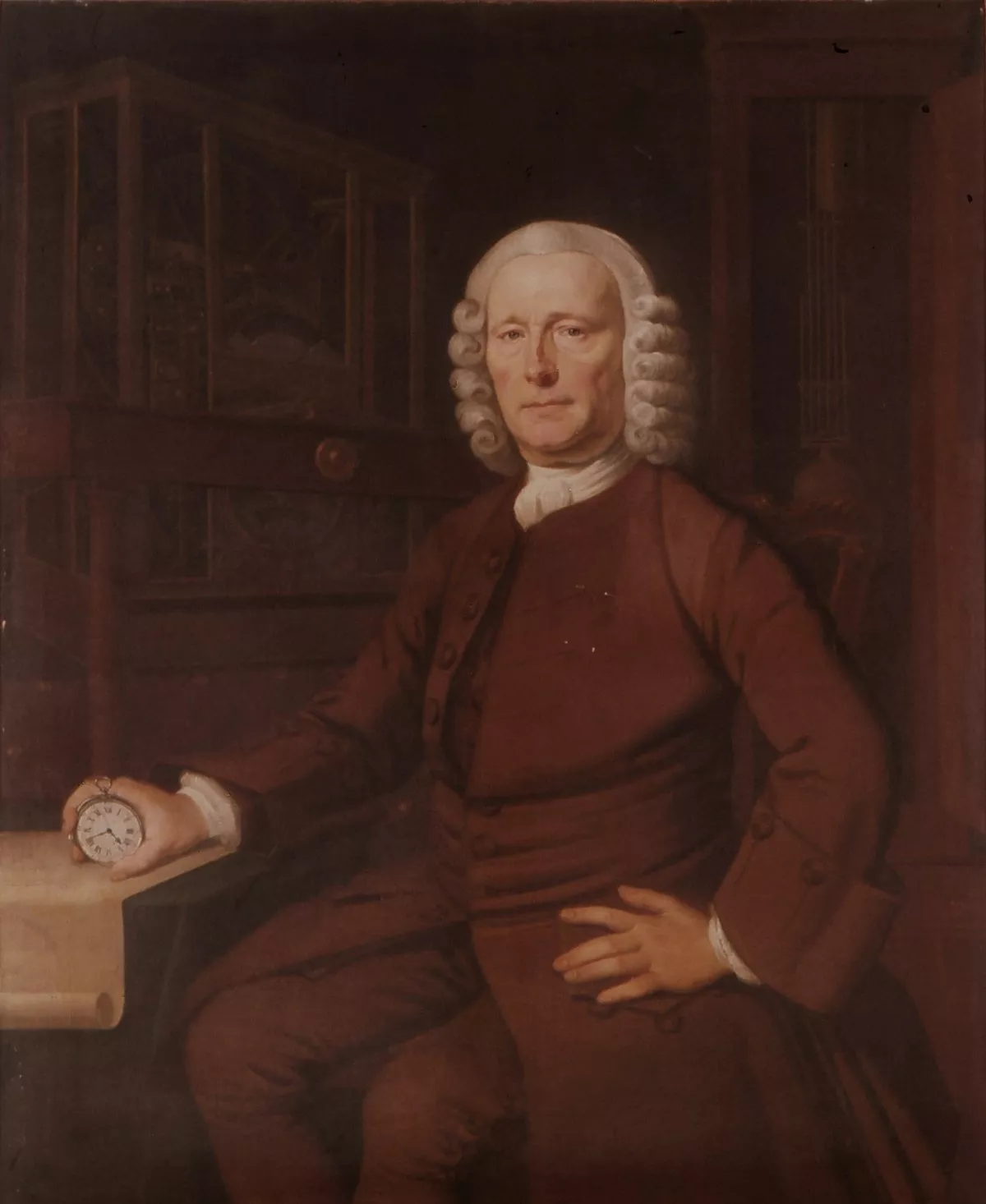

1. John Harrison presented his first design in 1730, and worked over many years on improved designs, making several advances in time-keeping technology, finally turning to what were called sea watches.

1.

1. John Harrison presented his first design in 1730, and worked over many years on improved designs, making several advances in time-keeping technology, finally turning to what were called sea watches.

John Harrison gained support from the Longitude Board in building and testing his designs.

John Harrison was born in Foulby in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the first of five children in his family.

John Harrison's stepfather worked as a carpenter at the nearby Nostell Priory estate.

Around 1700, the John Harrison family moved to the Lincolnshire village of Barrow upon Humber.

John Harrison had a fascination with music, eventually becoming choirmaster for the Church of Holy Trinity, Barrow upon Humber.

John Harrison built his first longcase clock in 1713, at the age of 20.

John Harrison was a man of many skills and he used these to systematically improve the performance of the pendulum clock.

John Harrison invented the gridiron pendulum, consisting of alternating brass and iron rods assembled in such a way that the thermal expansions and contractions essentially cancel each other out.

John Harrison was introduced to Graham by the Astronomer Royal Edmond Halley, who championed John Harrison and his work.

John Harrison set out to solve the problem directly, by producing a reliable clock that could keep the time of the reference place accurately over long intervals without having to constantly adjust it.

In 1730, John Harrison designed a marine clock to compete for the Longitude prize and travelled to London, seeking financial assistance.

John Harrison presented his ideas to Edmond Halley, the Astronomer Royal, who in turn referred him to George Graham, the country's foremost clockmaker.

John Harrison demonstrated it to members of the Royal Society who spoke on his behalf to the Board of Longitude.

John Harrison had moved to London by 1737 and went on to develop H2, a more compact and rugged version.

John Harrison had not recognized that the period of oscillation of the bar balances could be affected by the yawing action of the ship.

John Harrison spent seventeen years working on this third "sea clock", but despite every effort it did not perform exactly as he had wished.

The problem was that, because John Harrison did not fully understand the physics behind the springs used to control the balance wheels, the timing of the wheels was not isochronous, a characteristic that affected its accuracy.

John Harrison then realized that a mere watch after all could be made accurate enough for the task and was a far more practical proposition for use as a marine timekeeper.

John Harrison proceeded to redesign the concept of the watch as a timekeeping device, basing his design on sound scientific principles.

Importantly, John Harrison showed everyone that it could be done by using a watch to calculate longitude.

John Harrison returned a report of the watch that was negative, claiming that its "going rate" was due to inaccuracies cancelling themselves out, and refused to allow it to be factored out when measuring longitude.

Consequently, this first Marine Watch of John Harrison's failed the needs of the Board despite the fact that it had succeeded in two previous trials.

John Harrison began working on his second 'sea watch' while testing was conducted on the first, which John Harrison felt was being held hostage by the Board.

John Harrison obtained an audience with the King, who was extremely annoyed with the Board.

John Harrison was to live for just three more years.

John Harrison became the equivalent of a multi-millionaire in the final decade of his life.

John Harrison was buried in the graveyard of St John's Church, Hampstead, in north London, along with his second wife Elizabeth and later their son William.

John Harrison's tomb was restored in 1879 by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, even though Harrison had never been a member of the Company.

John Harrison's last home was 12 Red Lion Square in the Holborn district of London.

In February 2020, a bronze statue of John Harrison was unveiled in Barrow upon Humber.

Unfortunately, Gould made modifications and repairs that would not pass today's standards of good museum conservation practice, although most John Harrison scholars give Gould credit for having ensured that the historical artifacts survived as working mechanisms to the present time.

John Harrison drew a design but never built such a clock himself, but in 1970 Martin Burgess, a John Harrison expert and himself a clockmaker, studied the plans and endeavored to build the timepiece as drawn.

John Harrison built two versions, dubbed Clock A and Clock B Clock A became the Gurney Clock which was given to the city of Norwich in 1975, while Clock B lay unfinished in his workshop for decades until it was acquired in 2009 by Donald Saff.

Composer Peter Graham's piece John Harrison's Dream is about John Harrison's forty-year quest to produce an accurate clock.