1.

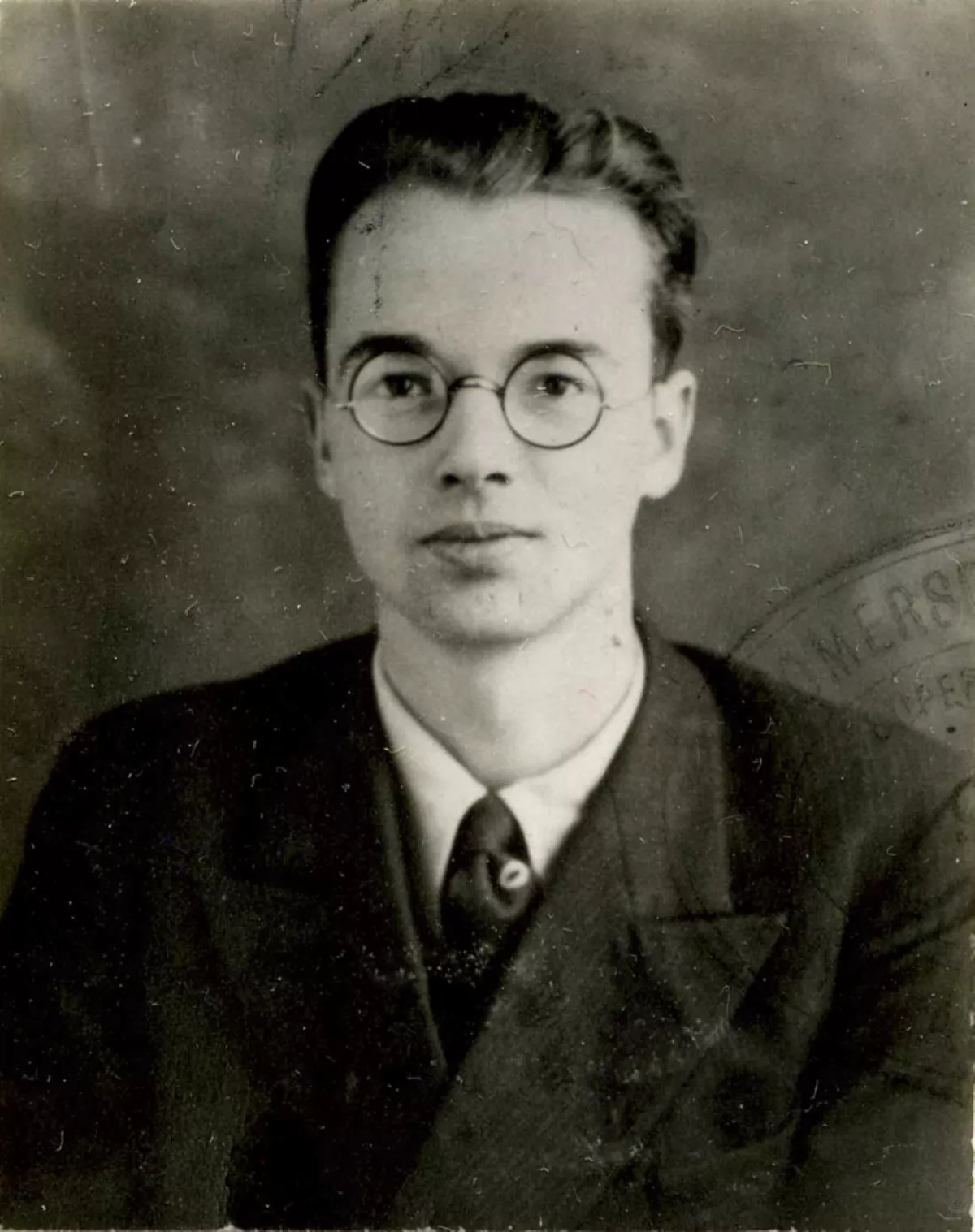

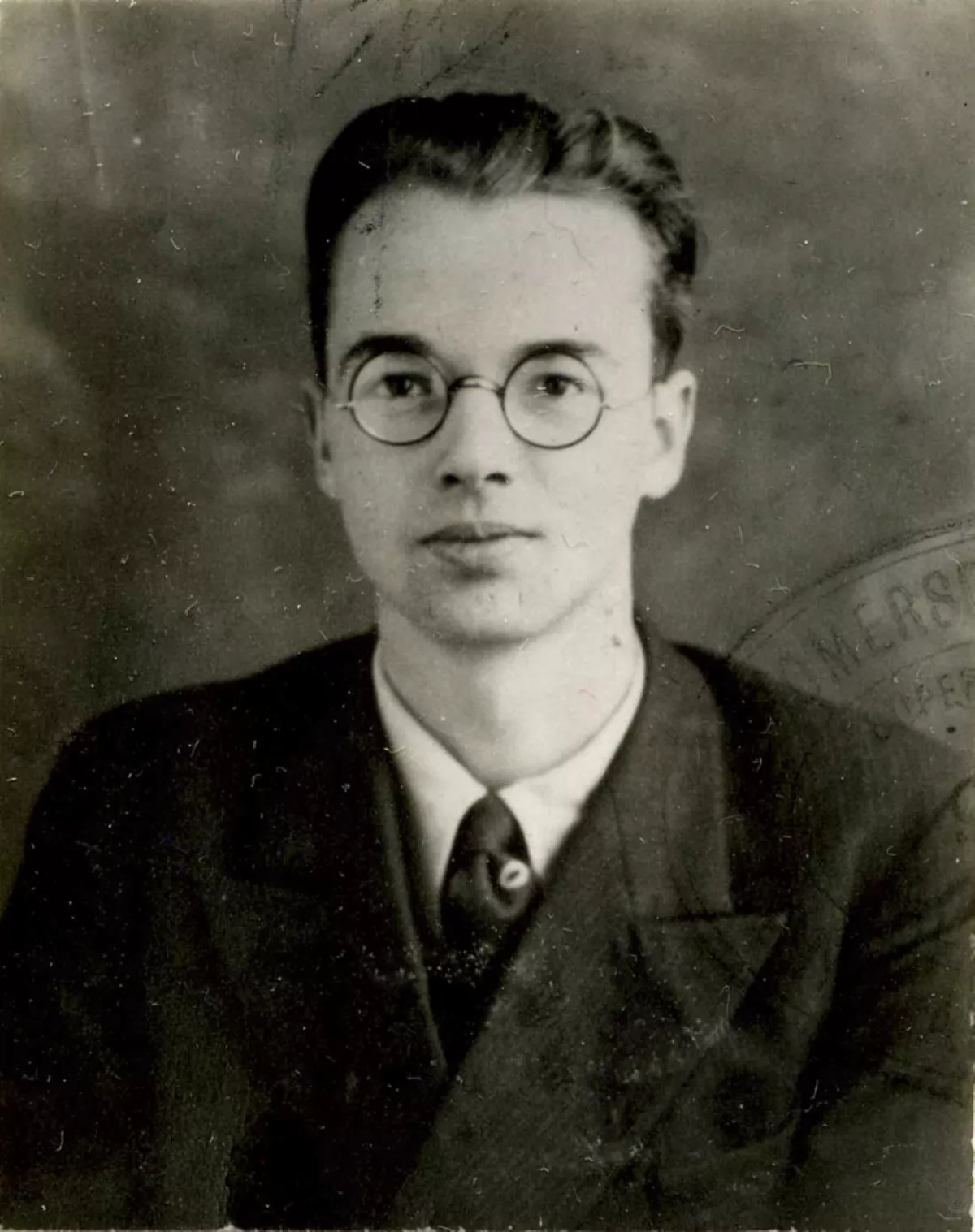

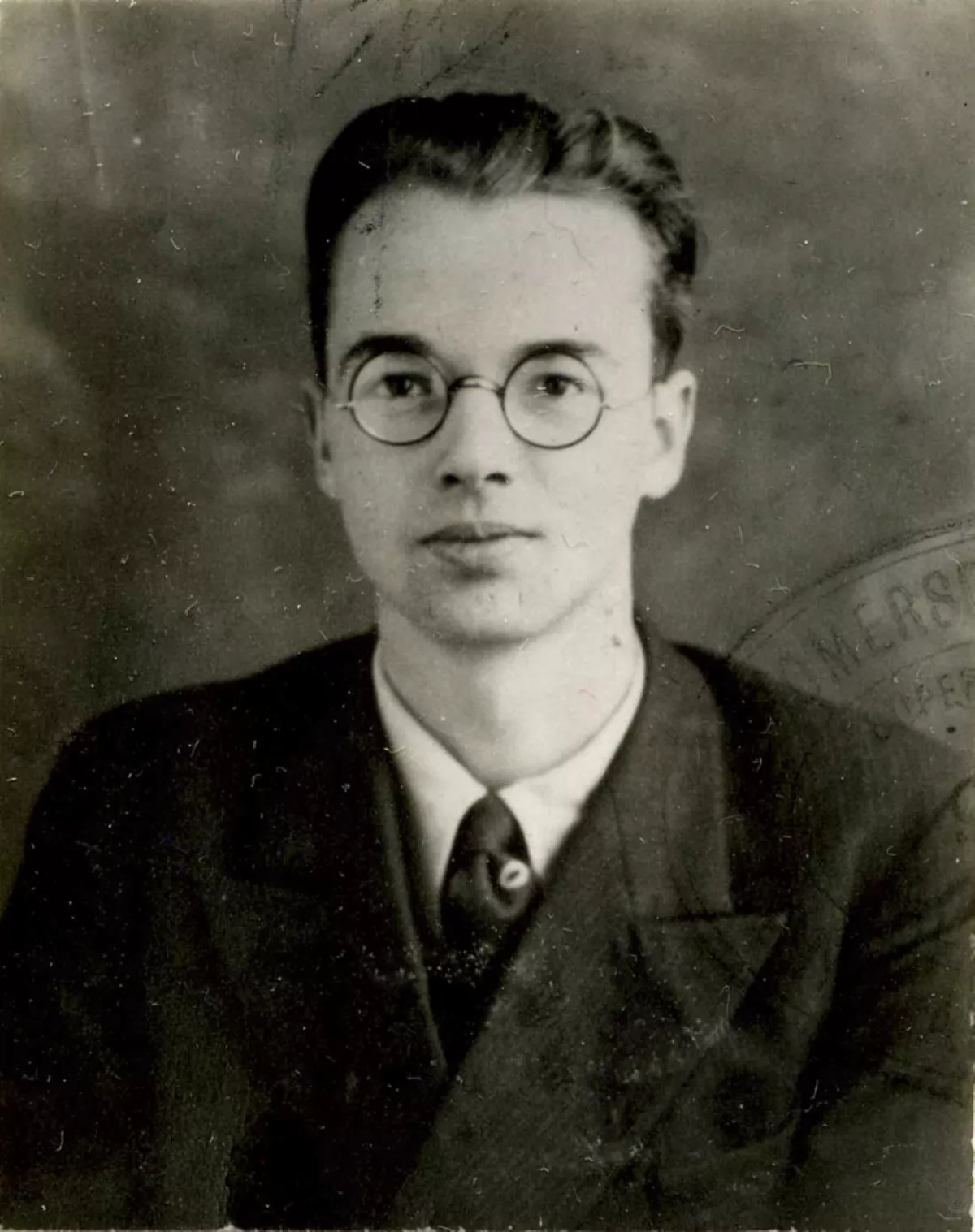

1. Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British, and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly after World War II.

1.

1. Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British, and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly after World War II.

The son of a Lutheran pastor, Klaus Fuchs attended the University of Leipzig, where his father was a professor of theology, and became involved in student politics, joining the student branch of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, and the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold, an SPD-allied paramilitary organisation.

Klaus Fuchs was expelled from the SPD in 1932, and joined the Communist Party of Germany.

Klaus Fuchs went into hiding after the 1933 Reichstag fire and the subsequent persecution of communists in Nazi Germany, and fled to the United Kingdom, where he received his PhD from the University of Bristol under the supervision of Nevill Francis Mott, and his DSc from the University of Edinburgh, where he worked as an assistant to Max Born.

Klaus Fuchs began passing information on the project to the Soviet Union through Ursula Kuczynski, codenamed "Sonya", a German communist and a major in Soviet military intelligence who had worked with Richard Sorge's spy ring in the Far East.

In January 1950, Klaus Fuchs confessed that he had passed information to the Soviets over a seven-year period beginning in 1942.

Klaus Fuchs was released in 1959, after serving nine years, and migrated to the German Democratic Republic, where he was elected to the Academy of Sciences and became a member of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany central committee.

Klaus Fuchs was later appointed deputy director of the Central Institute for Nuclear Physics in Dresden, where he served until his retirement in 1979.

Post Cold War declassified information states that the Russians freely acknowledged that Klaus Fuchs gave them the fission bomb.

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs was born in Russelsheim, Grand Duchy of Hesse, on 29 December 1911, the third of four children of a Lutheran pastor, Emil Fuchs, and his wife Else Wagner.

Klaus Fuchs's father served in the army during World War I but later became a pacifist and a socialist, joining the Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1912.

Klaus Fuchs had an older brother Gerhard, an older sister Elisabeth, and a younger sister, Kristel.

The family moved to Eisenach, where Klaus Fuchs attended the Martin-Luther Gymnasium, and took his Abitur.

Klaus Fuchs was left-handed, but was forced to write with his right hand.

Klaus Fuchs entered the University of Leipzig in 1930, where his father was a professor of theology.

Klaus Fuchs became involved in student politics, joining the student branch of the SPD, a party that his father had joined in 1921, and the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold, the party's paramilitary organisation.

Klaus Fuchs's father took up a new position as professor of religion at the Pedagogical Academy in Kiel, and in the autumn Fuchs transferred to the University of Kiel, which his brother Gerhard and sister Elisabeth attended.

Klaus Fuchs continued his studies in mathematics and physics at the university.

However, when the Communist Party of Germany ran its own candidate, Ernst Thalmann, Klaus Fuchs offered to speak for him, and was expelled from the SPD.

At one such gathering, Klaus Fuchs was beaten up and thrown into a river.

When Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, Klaus Fuchs decided to leave Kiel, where the NSDAP was particularly strong and he was a well-known KPD member.

Klaus Fuchs enrolled at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin.

Klaus Fuchs correctly assumed that opposition parties would be blamed for the fire, and surreptitiously removed his hammer and sickle lapel pin.

Klaus Fuchs went into hiding for five months in the apartment of a fellow party member.

Klaus Fuchs was expelled from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in October 1933.

Klaus Fuchs arranged for Fuchs to meet Nevill Francis Mott, Bristol's professor of physics, and he agreed to take Fuchs on as a research assistant.

Klaus Fuchs did not think that Fuchs would make much of a teacher, so he arranged a research post for Fuchs, at the University of Edinburgh working under Max Born, who was himself a German refugee.

Klaus Fuchs published papers with Born on "The Statistical Mechanics of Condensing Systems" and "On Fluctuations in Electromagnetic radiation" in the Proceedings of the Royal Society.

Klaus Fuchs received a Doctorate in Science degree from Edinburgh.

Klaus Fuchs proudly posted copies back to his father, Emil, in Germany.

Klaus Fuchs was arrested for speaking out against the government and was held for a month.

Klaus Fuchs returned to Berlin in 1934, where she too worked at the car rental agency.

Klaus Fuchs visited her brother, Klaus Fuchs, in England en route to America, where she eventually married an American communist, Robert Heineman, and settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Klaus Fuchs became a permanent resident in the United States in May 1938.

Klaus Fuchs applied to become a British subject in August 1939, but his application had not been processed before the Second World War broke out in Europe in September 1939.

Klaus Fuchs was Ursula Kuczynski, the sister of Jurgen Kuczynski.

Klaus Fuchs was a German communist, a major in Soviet Military Intelligence and an experienced agent who had worked with Richard Sorge's spy ring in the Far East.

In late 1943, Klaus Fuchs transferred along with Peierls to Columbia University, in New York City, to work on gaseous diffusion as a means of uranium enrichment for the Manhattan Project.

Klaus Fuchs spent Christmas 1943 with Kristel and her family in Cambridge.

Klaus Fuchs was contacted by Harry Gold, an NKGB agent in early 1944.

From August 1944, Klaus Fuchs worked in the Theoretical Physics Division at the Los Alamos Laboratory, under Hans Bethe.

At one point, Klaus Fuchs did calculation work that Edward Teller had refused to do because of lack of interest.

Klaus Fuchs was the author of techniques for calculating the energy of a fissile assembly that goes highly prompt critical, and his report on blast waves is still considered a classic.

Klaus Fuchs was one of the many Los Alamos scientists present at the Trinity test in July 1945.

Socially, Klaus Fuchs was later judged as someone who kept to himself, and never talked about politics.

Klaus Fuchs dated grade school teachers Evelyn Kline and Jean Parker, and occasionally served as a babysitter for other scientists.

When Klaus Fuchs was discovered to be a spy, his former colleagues were shocked.

Klaus Fuchs obviously worked with our people before and he is fully aware of what he is doing.

At the request of Norris Bradbury, who had replaced Robert Oppenheimer as director of the Los Alamos Laboratory in October 1945, Klaus Fuchs stayed on at the laboratory into 1946 to help with preparations for the Operation Crossroads weapons tests.

The US Atomic Energy Act of 1946 prohibited the transfer of information on nuclear research to any foreign country, including Britain, without explicit official authority, and Klaus Fuchs supplied highly classified US information to nuclear scientists in Britain and to his Soviet contacts.

Klaus Fuchs was highly regarded as a scientist by the British, who wanted him to return to the United Kingdom to work on Britain's postwar nuclear weapons programme.

Klaus Fuchs returned in August 1946 and became the head of the Theoretical Physics Division at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell.

Also in 1947, Klaus Fuchs attended a conference of the Combined Policy Committee, which was created to facilitate exchange of atomic secrets at the highest levels of governments of the United States, United Kingdom and Canada.

Under interrogation by MI5 officer William Skardon at an informal meeting in December 1949, Klaus Fuchs initially denied being a spy and was not detained.

In October 1949, Klaus Fuchs had approached Henry Arnold, the head of security at Harwell, with the news that his father had been given a chair at the University of Leipzig in East Germany, and this information became a factor as well.

Klaus Fuchs was offered help in finding a university post.

Klaus Fuchs told interrogators that the NKGB had acquired an agent in Berkeley, California, who had informed the Soviet Union about electromagnetic separation research of uranium-235 in 1942 or earlier.

Klaus Fuchs later stated that he passed detailed information on the project to the Soviet Union through courier Harry Gold in 1945, and further information about Edward Teller's unworkable "Super" design for a hydrogen bomb in 1946 and 1947.

Klaus Fuchs stated that "The last time when I handed over information [to Russian authorities] was in February or March 1949".

Klaus Fuchs was arrested on 2 February 1950, charged with violations of the Official Secrets Act.

Hans Bethe once said that Klaus Fuchs was the only physicist he knew to have truly changed history.

Klaus Fuchs stated that his best estimate is that the information furnished by him speeded up the production of an A-Bomb by Russia by several years because it permitted them to start on the development of the explosion [sic: explosive] and have this ready by the time the fissionable material was ready.

Klaus Fuchs concluded that the Russian scientists are as good as scientists in England and the United States but there are fewer good scientists in Russia than the other two countries.

Klaus Fuchs stated that he gave the Russians nothing that would speed up the production of plutonium and estimated that if he had given the same data which he gave the Russians to the United States as of the date of his arrival in the United States, he would have speeded the US production of the A-Bomb only slightly.

Klaus Fuchs did pass on to his Russian espionage contact what he learned concerning the production of plutonium during the final period of his work at Los Alamos.

Klaus Fuchs stated that the information furnished by him alone could have speeded up the production of an A-Bomb by Russia by one year at least.

Klaus Fuchs indicated that if the Russians had information on the plutonium process from any other source, the data furnished by him could have been of material assistance on this plutonium phase.

Klaus Fuchs was not told how the Soviets would or would not use his information, and though certain questions from his espionage contacts suggested to him that the Soviets had additional sources within the Manhattan Project, he was unaware of their identities and knowledge.

The information that Klaus Fuchs was able to give the Soviet Union about the Manhattan Project was much more extensive, and much more technically precise, than that available from other, later-discovered atomic spies like David Greenglass or Theodore Hall.

Whether the information Klaus Fuchs passed relating to the hydrogen bomb would have been useful is still debated.

The revelation of Klaus Fuchs's espionage increased the rift between the United States and the United Kingdom on matters of atomic energy.

Klaus Fuchs consented to the advice not to raise the question of inducement in his decision to admit guilt.

Klaus Fuchs was released on 23 June 1959 after he had served nine years and four months of his sentence at Wakefield Prison and promptly emigrated to the German Democratic Republic.

Klaus Fuchs became a member of the SED central committee in 1967, and in 1972 was elected to the Academy of Sciences where from 1974 to 1978 he was the head of the research area of physics, nuclear and materials science; he was then appointed deputy director of the Central Institute for Nuclear Physics in Rossendorf, Dresden, where he served until he retired in 1979.

From 1984, Klaus Fuchs was head of the scientific councils for energetic basic research and for fundamentals of microelectronics.

Klaus Fuchs received the Patriotic Order of Merit, the Order of Karl Marx and the National Prize of East Germany.

Klaus Fuchs was cremated and honoured with burial in the section of Berlin's Friedrichsfelde Cemetery.

Klaus Fuchs was portrayed by Denis Forest in the 1987 television miniseries Race for the Bomb.

In 2022, Klaus Fuchs was the primary focus of the second season of the BBC World Service's podcast The Bomb.

Klaus Fuchs is portrayed by American actor Christopher Denham in the 2023 film Oppenheimer.