1.

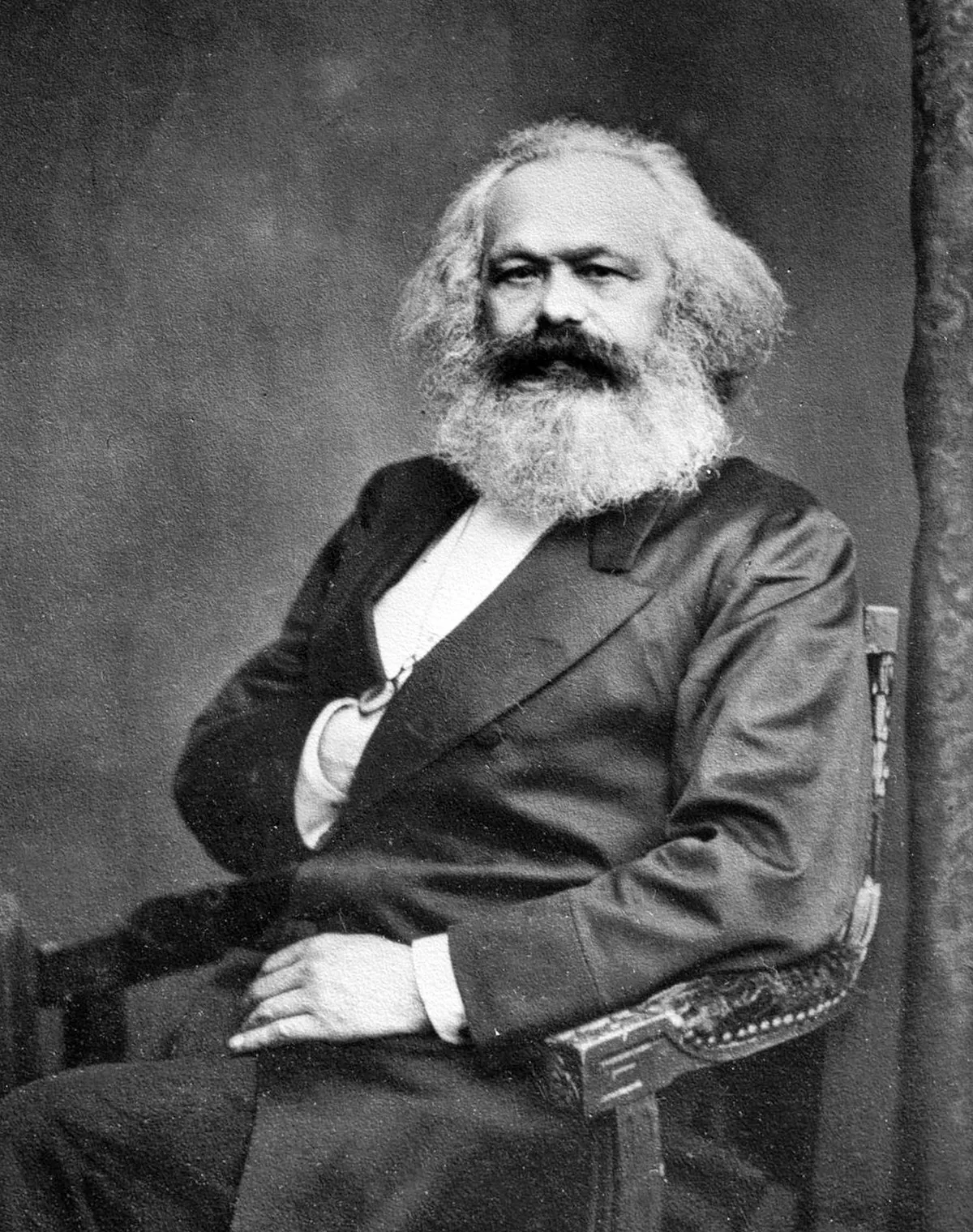

1. Karl Marx is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto, and his three-volume, a critique of classical political economy which employs his theory of historical materialism in an analysis of capitalism, in the culmination of his life's work.