1.

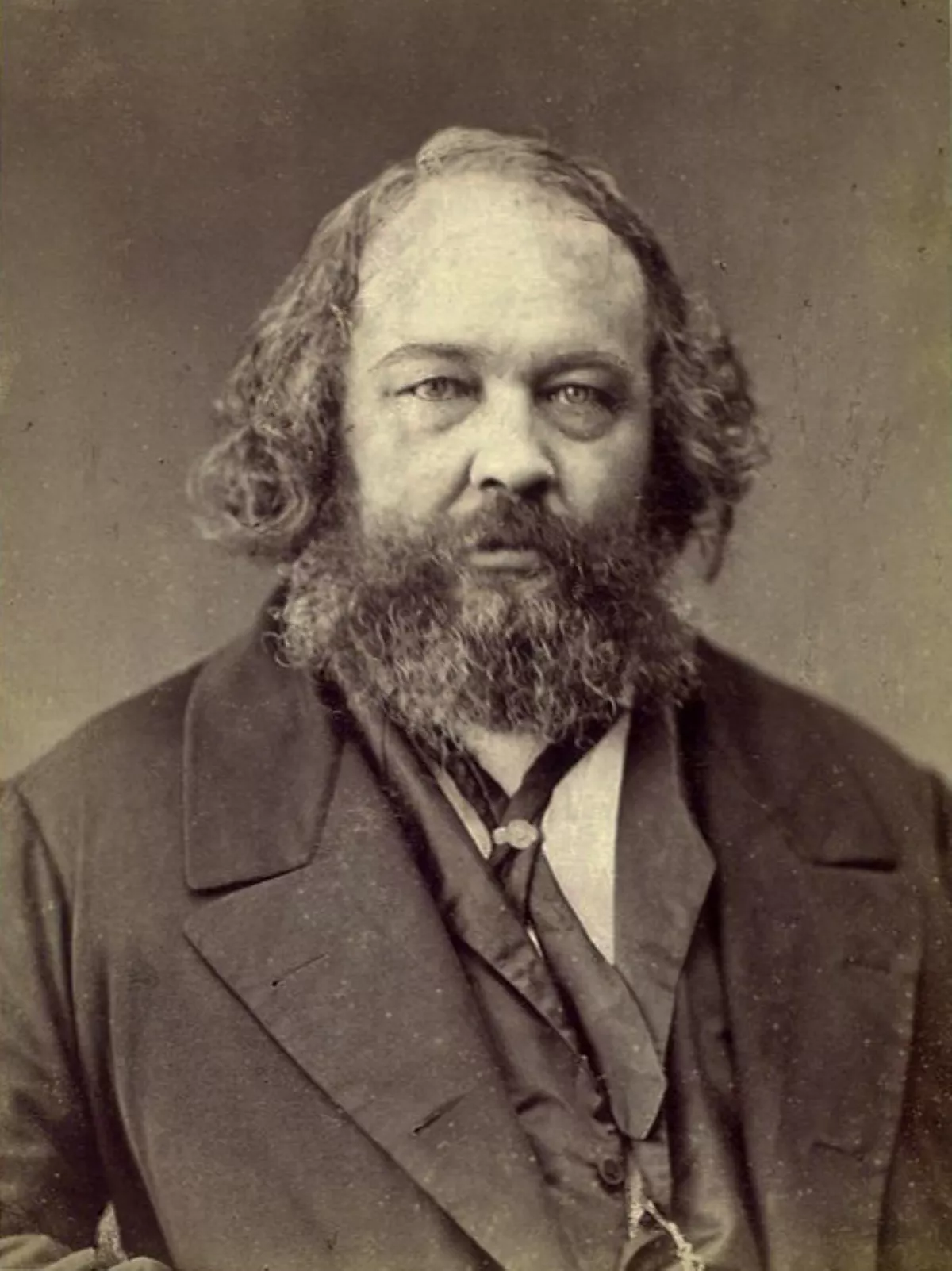

1. Mikhail Bakunin is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, social anarchist, and collectivist anarchist traditions.

1.

1. Mikhail Bakunin is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, social anarchist, and collectivist anarchist traditions.

Mikhail Bakunin grew up in Pryamukhino, a family estate in Tver Governorate.

Mikhail Bakunin was expelled from France for opposing the Russian Empire's occupation of Poland.

In 1863, Mikhail Bakunin left to join the insurrection in Poland, but he failed to reach it and instead spent time in Switzerland and Italy.

In 1868, Mikhail Bakunin joined the International Workingmen's Association, leading the anarchist faction to rapidly grow in influence.

The 1872 Hague Congress was dominated by a struggle between Mikhail Bakunin and Marx, who was a key figure in the General Council of the International and argued for the use of the state to bring about socialism.

Mikhail Bakunin was expelled from the International for maintaining, in Marx's view, a secret organisation within the International, and founded the Anti-Authoritarian International in 1872.

From 1870 until his death in 1876, Mikhail Bakunin wrote his longer works such as Statism and Anarchy and God and the State, but he continued to directly participate in European worker and peasant movements.

Mikhail Bakunin sought to take part in an anarchist insurrection in Bologna, Italy, but his declining health forced him to return to Switzerland in disguise.

Mikhail Bakunin is remembered as a major figure in the history of anarchism and as an opponent of Marxism, especially of the dictatorship of the proletariat, arguing that Marxist states would be one-party dictatorships ruling over the proletariat, not ruled by the proletariat.

Mikhail Bakunin's father, Alexander Mikhailovich Bakunin, was a Russian diplomat who had served in Italy.

Mikhail Bakunin deserted the school in 1835 and only escaped arrest through his familial influence.

Mikhail Bakunin was discharged at the end of the year and, despite his father's protests, left for Moscow to pursue a career as a mathematics teacher.

Mikhail Bakunin lived a bohemian, intellectual life in Moscow, where German Romantic literature and idealist philosophy were influential in the 1830s.

Mikhail Bakunin produced the first Russian translation of Hegel and was the foremost Russian expert on Hegel by 1837.

Mikhail Bakunin befriended Russian intellectuals including the literary critic Vissarion Belinsky, the poet Nikolay Ogarev, the novelist Ivan Turgenev, and the writer Alexander Herzen as youth prior to their careers.

In Berlin, Mikhail Bakunin gravitated towards the Young Hegelians, an intellectual group with radical interpretations of Hegel's philosophy, and who drew Mikhail Bakunin to political topics.

Mikhail Bakunin left Berlin in early 1842 for Dresden and met the Hegelian Arnold Ruge, who published Bakunin's first original publication.

When his cadre aroused interest from Russian secret agents, Mikhail Bakunin left for Zurich in early 1843.

Mikhail Bakunin met the proto-communist Wilhelm Weitling whose arrest led Bern's Russian embassy to distrust Bakunin.

Mikhail Bakunin visited Brussels and Paris, where he joined international emigrants and socialists, befriended the anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and met the philosopher Karl Marx, with whom he would later tussle.

Mikhail Bakunin only became personally active in political agitation in 1847, as Polish emigrants in Paris invited him to commemorate the 1830 Polish uprising with a speech.

Mikhail Bakunin's call for Poles to overthrow czarism in alliance with Russian democrats made Bakunin known throughout Europe and led the Russian ambassador to successfully request Bakunin's deportation.

Mikhail Bakunin attended the 1848 Prague Slavic Congress to defend Slavic rights against German and Hungarian nationalism, and participated in its impromptu insurrection against the Austrian Habsburgs.

Prison weathered but did not break Mikhail Bakunin, who retained his revolutionary zeal through his release.

Mikhail Bakunin did write an autobiographical, genuflecting Confession to the Russian emperor, which proved to be a controversial document upon its public discovery some 70 years later.

In 1857, Mikhail Bakunin was permitted to transfer to permanent exile in Siberia.

Mikhail Bakunin married Antonia Kwiatkowska there before escaping in 1861, first to Japan, then to San Francisco, sailing to Panama and then to New York and Boston, and arrived in London by the end of the year.

Mikhail Bakunin set foot in America just as the Civil War was breaking out.

Mikhail Bakunin viewed the Southern political system and agrarian character as freer in some respects for its white citizens than in the industrial North.

Mikhail Bakunin collaborated with them on their Russian-language newspaper but his revolutionary fervor exceeded their moderate reform agenda.

Mikhail Bakunin, reunited with his wife, moved to Italy the next year, where they stayed for three years.

Mikhail Bakunin continued to refine these ideas in his remaining 12 years.

Mikhail Bakunin moved to Switzerland in 1867, a more permissive environment for revolutionary literature.

Not knowing Nechayev's past betrayals, Mikhail Bakunin warmed to Nechayev's revolutionary zeal and they together produced the 1869 Catechism of the Revolutionary, a tract that endorsed an ascetic life for revolutionaries without societal or moral bonds.

Mikhail Bakunin respected Marx's erudition and passion for socialism but found his personality to be authoritarian and arrogant.

Mikhail Bakunin's ideas continued to spread nevertheless to the labor movement in Spain and the watchmakers of the Swiss Jura Federation.

Mikhail Bakunin wrote his last major work, Statism and Anarchy, anonymously in Russian to stir underground revolution in Russia.

In one final revolutionary act, Mikhail Bakunin planned the unsuccessful 1874 Bologna insurrection with his Italian followers.

Mikhail Bakunin retreated to Switzerland, where he retired, dying in Bern on 1 July 1876.

Mikhail Bakunin unsuccessfully sought community in religion and philosophy through influences including Arnold Ruge, Ludwig Feuerbach, Wilhelm Weitling, and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

Mikhail Bakunin turned from metaphysics and theory to the practice of creating communities of free, independent people.

For Mikhail Bakunin, freedom required community and equality, including equality in rights and social functions for women.

Mikhail Bakunin envisioned an international revolution by the awakened masses that would bring about new forms of social organization in a large-scale federation undoing all state structure and social coercion.

Mikhail Bakunin did not believe a reformed bourgeois or revolutionary state could emancipate like such a community he described, so his vision of revolution meant not capturing power but ensuring that no new power took the place of the old.

Mikhail Bakunin was not a systematic thinker and did not design grand systems or theoretical constructs.

Mikhail Bakunin was prone to large digressions and rarely completed what he set out to address.

Mikhail Bakunin saw the institutions of church and state as standing against the aims of emancipatory community, namely that they impose wisdom and justice from above under the pretense that the masses could not fully self-govern.

Mikhail Bakunin wrote that "to exploit and to govern mean the same thing".

Mikhail Bakunin held the State as a regulated system of domination and exploitation by a privileged, ruling class.

Mikhail Bakunin regarded representative democracies as a paradoxical abstraction from social reality.

Mikhail Bakunin believed that powerful institutions to be inherently stronger than individual will and incapable of internal reform due to the overwhelming ambitions and temptations that corrupt those with power.

Mikhail Bakunin clashed with Marx over worker governance and revolutionary change.

Mikhail Bakunin argued that even the best revolutionary placed on the Russian throne would become worse than Czar Alexander.

Mikhail Bakunin wrote that socialist workers in power would become ex-workers who govern by their own pretensions, not representing the people.

Mikhail Bakunin did not believe in transitional dictatorship serving any purpose other than to perpetuate itself, saying that "liberty without socialism is privilege and injustice, and socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality".

Mikhail Bakunin disagreed with Marx that the state would wither away under worker ownership and that worker conquest and changes in production conditions would inherently kill the state.

Mikhail Bakunin promoted spontaneous worker actions over Marx's suggested organization of a working-class party.

Mikhail Bakunin wrote of referring to the "authority to the bootmaker" on boots and to savants for their specialties, and listening to them freely in respect for their expertise, but not allowing the bootmaker or the savant to impose this authority and not letting them be beyond criticism or censure.

Mikhail Bakunin believed that authority should be in continual voluntary exchange rather than a constant subordination.

Mikhail Bakunin believed intelligence to have intrinsic benefits so as to not require additional privileges.

Towards the end of his life, beginning in 1864 in Italy with the International Brotherhood, Mikhail Bakunin attempted to unite his international network under secret revolutionary societies, a concept at odds with his professed caution against the autocratic tendencies of the revolutionary elite.

Mikhail Bakunin's written programs played a larger role in his politics than these draft secret societies.

Mikhail Bakunin married Antonia Kwiatkowska, originally from Poland, during his exile in Siberia.

Kwiatkowska was much younger than Mikhail Bakunin and had little interest in politics.

Mikhail Bakunin was the leading anarchist revolutionary of the 19th century, active from the 1840s through the 1870s.

Mikhail Bakunin's legacy reflects the paradox and ambivalence by which he lived.

Mikhail Bakunin archives are held in several places: the Pushkin House, the State Archive of the Russian Federation, the Russian State Library, the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, the National Library of Russia, and the International Institute of Social History.