1.

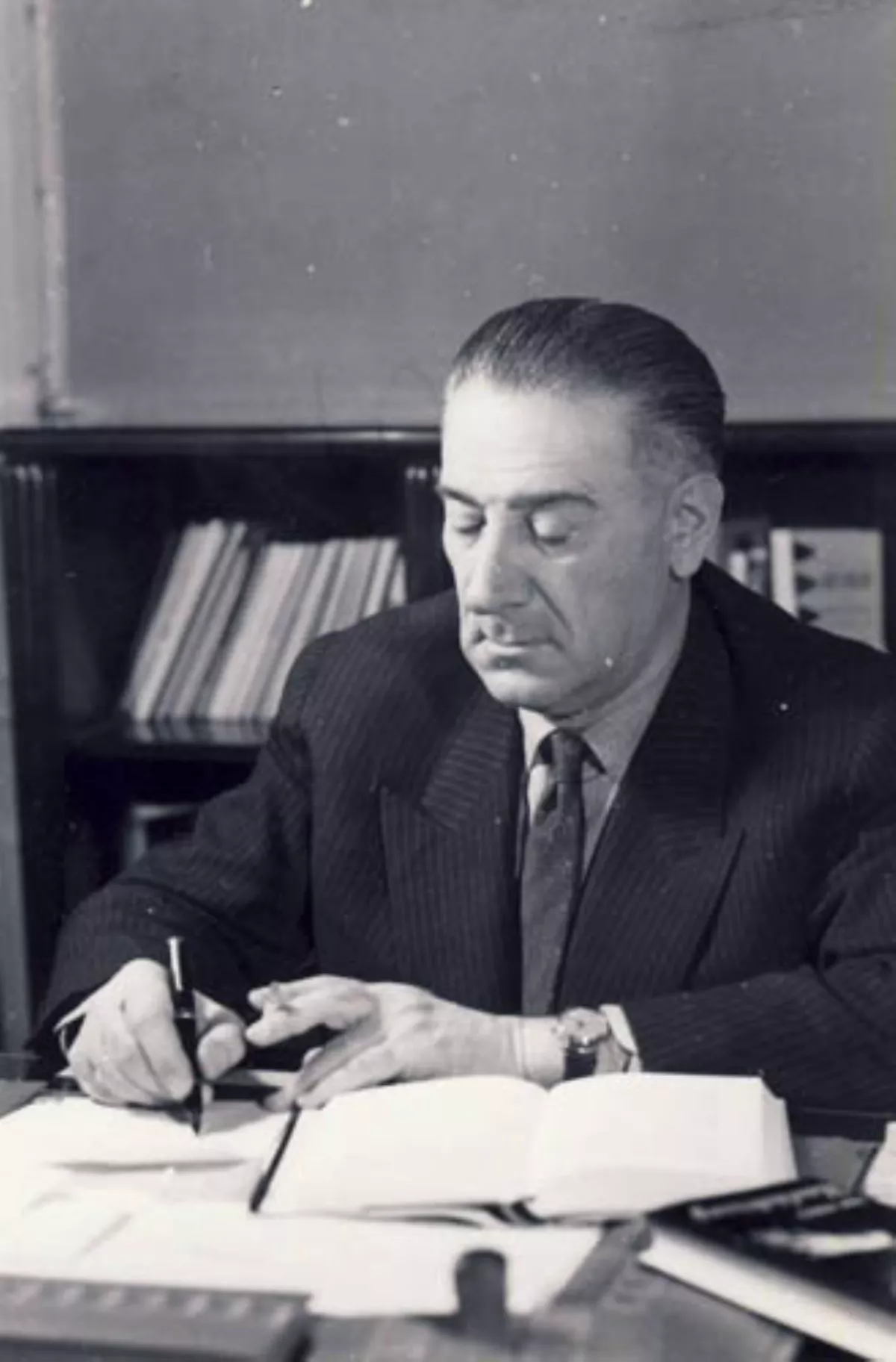

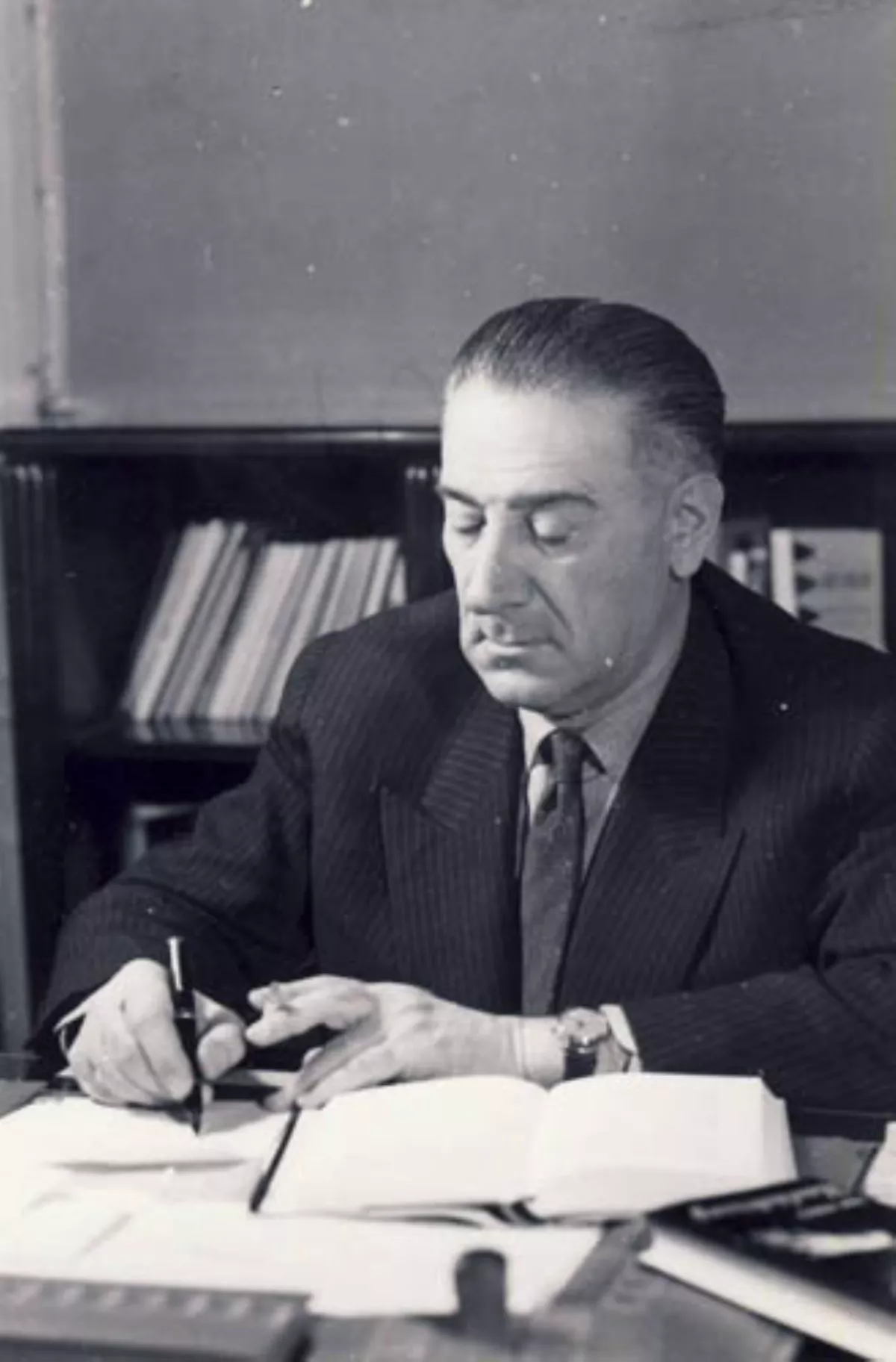

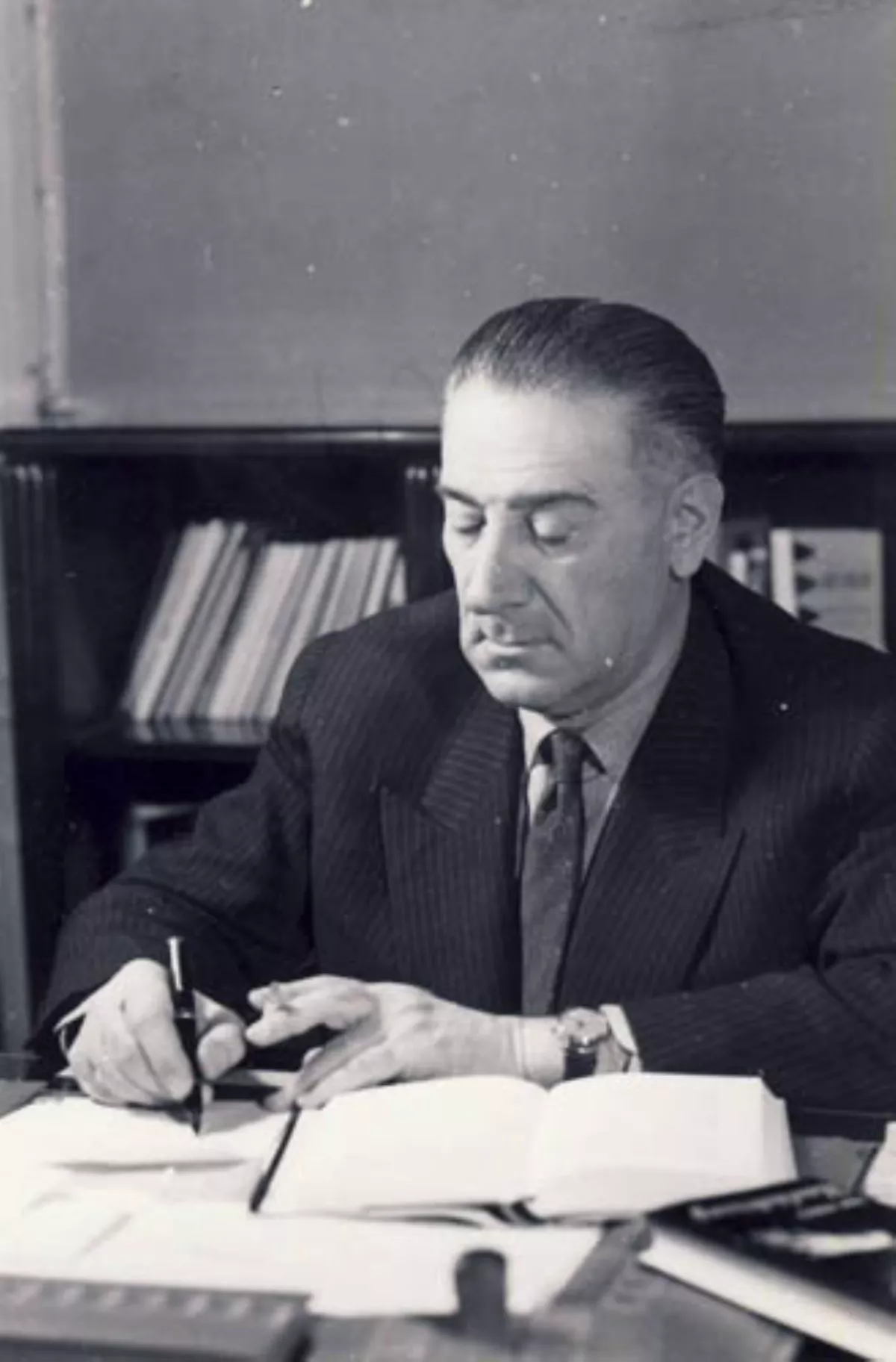

1. Mihai Dumitru Ralea was a Romanian social scientist, cultural journalist, and political figure.

1.

1. Mihai Dumitru Ralea was a Romanian social scientist, cultural journalist, and political figure.

Mihai Ralea debuted as an affiliate of Poporanism, the left-wing agrarian movement, which he infused with influences from corporatism and Marxism.

Mihai Ralea viewed Romanians as naturally skeptical and easy-going, and was himself perceived as flippant; though he was nominally active in experimental psychology, he questioned its scientific assumptions, and preferred an interdisciplinary system guided by intuition and analogies.

Mihai Ralea was a professor at the University of Iasi and, from 1938, the University of Bucharest.

Mihai Ralea had publicized polemics with the far-right circles and fascist Iron Guard, which he denounced as alien to the Romanian ethos; Ralea approximated a Poporanist, leftist, take on Romanian nationalism, which he opposed to both fascism and communism.

Mihai Ralea later drifted apart from the party's centrist leadership and his own democratic ideology, setting up a Socialist Peasants' Party, then embracing authoritarian politics.

Mihai Ralea was a founding member and Labor Minister of the dictatorial National Renaissance Front, representing its corporatist left-wing.

Mihai Ralea fell from power in 1940, finding himself harassed by successive fascist regimes, and became a "fellow traveler" of the underground Communist Party.

Mihai Ralea willingly cooperated with the communists and the Ploughmen's Front before and after their arrival to power, serving as Minister of Arts, Ambassador to the United States, and vice president of the Great National Assembly.

Mihai Ralea's missions coincided with the inauguration of a Romanian communist regime, whose policies he privately feared and resented.

Mihai Ralea was sidelined, then recovered, and, as a Marxist humanist, was one of the regime's leading cultural ambassadors by 1960.

Heavily controlled by communist censorship, his work gave scientific credentials to the communist rulers' anti-American propaganda, though Mihai Ralea used his position to protect some of those persecuted by the authorities.

Mihai Ralea died abroad, while on mission to the UNESCO, and was posthumously diagnosed with a neurological disease.

Mihai Ralea was survived by two daughters, one of whom was Catinca Ralea, who achieved literary fame as a translator of Western literature.

Mihai Ralea's son was always spiritually attached to his native region and, later in life, bought himself a vineyard on Dobrina Hill, just outside Husi, building himself a vacation home.

Mihai Ralea completed his primary education at Husi School No 2, before he moved on to the urban center of Iasi, where he enlisted at the Boarding High School, studying the classics.

Mihai Ralea went on to attend the University of Bucharest Faculty of Letters and Philosophy, under Constantin Radulescu-Motru.

Mihai Ralea was university colleagues with philosophers Tudor Vianu and Nicolae Bagdasar, who joined his circle of intimate friends.

Mihai Ralea took his final examination in Law and Letters at the University of Iasi, in 1918.

Mihai Ralea's professors included the culture critic Garabet Ibraileanu, who became Ralea's mentor.

Mihai Ralea recalled that his first encounter with Ibraileanu was "my life's greatest intellectual event".

Poporanism was generally pro-Westernization, with a noted reserve; taken separately, Mihai Ralea was the most pro-Western, socialist, and least culturally conservative thinker of this category.

Mihai Ralea entered the Ecole Normale Superieure as a disciple of Lucien Herr, simultaneously registering for doctoral programs in letters and politics, with interests in sociology and psychology.

Mihai Ralea studied under the functionalist Celestin Bougle, then under Paul Fauconnet and Lucien Levy-Bruhl, and later, at the College de France, under Pierre Janet.

Young Mihai Ralea defined himself as a rationalist, heir to the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution, and was ostensibly an atheist.

Mihai Ralea's later friend and disciple psycholinguist, Tatiana Slama-Cazacu, suggests that he was a "salon socialist" who came to rely on his anti-socialist father's fortune so as to maintain his Parisian lifestyle.

Mihai Ralea was part of a tight cell of Romanian students in letters or history, which included Otetea, Gheorghe Bratianu, and Alexandru Rosetti, who remained close friends over the decades.

Mihai Ralea became its foreign correspondent, sending in articles about the intellectual life and philosophical doctrines of the Third Republic, and possibly the first Romanian notices about the work of Marcel Proust.

In 1922, Mihai Ralea took his Docteur d'Etat degree with L'idee de la revolution dans les doctrines socialistes.

Under the Francized name Michel Mihai Ralea, he published it at Riviere company in 1923.

Mihai Ralea spent another several months frequenting lectures at the University of Berlin.

Mihai Ralea was involved with Dimitrie Gusti and Virgil Madgearu's Romanian Social Institute, publishing his texts in its Arhiva pentru Stiinta si Reforma Sociala.

Mihai Ralea had married Ioana Suchianu in November 1923, while still in Bucharest, and lived with her in a small apartment above the Viata Romaneasca offices.

Mihai Ralea published the tract Formatia ideii de personalitate, noted as a pioneering introduction to behavioural genetics.

On January 1,1926, following good referrals from Petrovici, Ralea was appointed Professor of Psychology and Aesthetics at the University of Iasi.

Mihai Ralea soon became one of Viata Romaneascas ideologues and polemicists, as well as architect of its satire column, Miscellanea.

Mihai Ralea's essays were taken up by other cultural magazines throughout Romania, including Kalende of Pitesti and Minerva of Iasi.

In 1927, when Mihai Ralea published his Contributiuni la stiinta societatii and Introducere in sociologie, Gusti's Social Institute had Mihai Ralea as a guest speaker, with a lecture on "Social Education".

At around that time, with Gusti as president of the Broadcasting Company, Mihai Ralea became a frequent presence on the radio.

Mihai Ralea opined that Poporanist ideas were still culturally relevant, and not in fact isolationist, since they provided a recipe for "originality"; as he put it, "national specificity" had become inevitable.

The conflict was not just political: Mihai Ralea objected to modernist aesthetics, from the pure poetry cultivated by Sburatorul to the more radical Constructivism of Contimporanul magazine.

Mihai Ralea was not an anti-modernist, but rather a particular modernist.

Mihai Ralea campaigned for social realism in prose.

Mihai Ralea did not object to Crainic's Romanian Orthodox devotion, but mainly to his national conservatism, which worshiped the historical past.

In reply, Mihai Ralea noted that, beyond their facade, national and religious conservatism meant a reinstatement of primitive customs, obscurantism, Neoplatonism, and Byzantinism.

Mihai Ralea pushed the envelope by demanding a program of forced Westernization and secularization, to mirror Kemalism.

Mihai Ralea's comments challenged the grounding of Gandirist theory: Romanian Orthodoxy, he noted, was part of an international Orthodox phenomenon that mainly included Slavs, whereas many Romanians were Greek-Catholic.

Mihai Ralea concluded, therefore, that Orthodoxy could never claim synonymy with the Romanian ethos.

Mihai Ralea insisted that, despite its nativist anti-Western claims, Orthodox religiousness was a modern "trifle", that owed inspiration to Keyserling's Theosophy and Cocteau's Catholicism.

Mihai Ralea collected his critical essays as a set of volumes: Comentarii si sugestii, Interpretari, Perspective.

Mihai Ralea was still involved in psychological research, with tracts such as Problema inconstientului and Ipoteze si precizari privind stiinta sufletului.

Mihai Ralea resumed his European travels, touring the Kingdom of Spain, and was unenthusiastic about its conservatism.

Mihai Ralea was one of a compact group of National Peasantist academics in Poporanist Iasi, together with Botez, Otetea, Constantin Balmus, Iorgu Iordan, Petre Andrei, Traian Bratu, and Traian Ionascu.

Inside the party, Mihai Ralea was a follower of the Poporanist founding figure, Constantin Stere, but did not follow Stere's "Democratic Peasantist" dissidence of 1930.

Around 1929, Mihai Ralea was a noted contributor to the party press organ Actiunea Taranista and to Teodorescu-Braniste's Revista Politica.

Mihai Ralea eventually affiliated with the centrist current of the PNT, distancing himself from those party factions who were tempted by socialism.

Mihai Ralea defended classical parliamentarianism at several Inter-Parliamentary Union meetings, including the 1933 conference in the Republic of Spain, but insisted on the benefits of statism and a planned economy.

Mihai Ralea now owned an Iasi townhouse and a villa in Bucharest's Filipescu Park.

Mihai Ralea's energies were drawn into administrative disputes and professional rivalries.

Mihai Ralea tried to do the same for Rosetti, but was met with the stiff opposition of linguist Giorge Pascu.

From 1934 to March 1938, Mihai Ralea was editor of the main PNT newspaper, Dreptatea.

Mihai Ralea contributed its political editorials, answering to criticism from the right.

In Dreptatea, addressing Universul editor Pamfil Seicaru, Mihai Ralea dismissed suspicions that the "peasant state" signified a "simplistic domination" or a dictatorship of the peasantry.

Mihai Ralea had his own brush with the Guard in late 1932, when he was presiding upon symposiums on French literature at Criterion society.

In 1935,161 of Mihai Ralea's essays were collected and published at Editura Fundatiilor Regale as Valori.

Mihai Ralea synthesized his critique of fascism in the 1935 essays on "The Right's Doctrine", taken up by Dreptatea and Viata Romaneasca.

Mihai Ralea's assessments were countercriticized by Guardist intellectual Toma Vladescu, in the newspaper Porunca Vremii.

Mihai Ralea became one of the PNT men affiliated with Lord Cecil's International Peace Campaign, which, in Romania, was dominated by PSDR militants.

Mihai Ralea had rapports with the outlawed Romanian Communist Party : with Dem I Dobrescu, he formed a committee to defend jailed communists such as Alexandru Draghici and Teodor Bugnariu.

Mihai Ralea was supported by his sister Eliza, who contributed to the International Red Aid.

In 1937, with an obituary piece to the "martyr" Stere, Mihai Ralea defended Poporanism from accusations of "Bolshevik" subservience.

In January 1937, at the PNT Youth Conference in Cluj, Mihai Ralea spoke of the "peasant state" as a "neo-nationalist" application of democratic socialism, opposed to fascism, and in natural solidarity with the trade unions.

Mihai Ralea felt confident that this alliance would be powerful enough to outweigh fashionable totalitarianism.

Consequently, Mihai Ralea campaigned in his native Falciu County alongside the movement's candidates, in terms he would later describe as "cordial".

Mihai Ralea was promptly stripped of his PNT membership, and inaugurated his own party, the exceedingly minor Socialist Peasants' Party.

Mihai Ralea himself claimed that the king cultivated his friendship as a likable "communist", though, as Camelia Zavarache argues, there is no secondary proof to attest that Mihai Ralea was ever part of Carol's camarilla.

At the time, PNT activists began collecting evidence that Mihai Ralea was not an ethnic Romanian, which meant that he could no longer hold public office under the Romanianization laws.

Mihai Ralea himself was involved in the Romanianization campaign: in late 1938, he accepted Wilhelm Filderman's proposal for the mass emigration of Romanian Jews.

Toward the end of 1938, Mihai Ralea moved from his old chair at the University of Iasi and took up a similar position at his Bucharest alma mater.

Mihai Ralea appropriated socialist propaganda, and attracted more or less sizable contributions from various centrists and left-wingers: Sadoveanu, Vianu, Suchianu, Philippide, as well as Demostene Botez, Octav Livezeanu, Victor Ion Popa, Gala Galaction, Barbu Lazareanu, and Ion Pas.

Mihai Ralea's mandate was a crossover of left-wing corporatism and fascism.

Mihai Ralea's MVB was directly inspired by Strength Through Joy and the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro.

In 1939, Mihai Ralea celebrated May Day with a large parade of support for Carol II.

In underground PSDR circles, as well as in inside the ministerial structures, rumors spread that Mihai Ralea was using secret funds at his discretion to sponsor various PCdR militants, including his schoolmate Petre Constantinescu-Iasi; these stories were partly confirmed by Mihai Ralea himself.

Mihai Ralea was his friend and confidant, and, as he later claimed, defended Calinescu against the "mythomaniacal" Iron Guard.

Mihai Ralea claimed to have protected Guardsmen employed by the Labor Ministry, and to have negotiated pardons for militants interned at Miercurea Ciuc.

Himself a Guard sympathizer, Ion Barbu later claimed that Mihai Ralea was behind his marginalization in academia.

Mihai Ralea was accused by Pandrea of having done nothing to prevent the arrest of his former Dreptatea colleague, the anti-Carol PNT-ist Madgearu.

Various reports on both sides confirm that Mihai Ralea was in permanent contact with Soviet diplomats, arranged for him by Constantinescu-Iasi and Belu Zilber.

Mihai Ralea was still being given new responsibilities within the FRN structure.

In later years, Mihai Ralea confided to his friends that he was sure he would be killed on that night, and that it was in fact Herseni who had pleaded for his release.

Antonescu castigated the Commission for Review as a "shame", and declared Mihai Ralea to be "indispensable".

Still present in public life after the Romania's entry into the anti-Soviet war, Mihai Ralea returned to publishing with articles in Revista Romana and the 1942 book Intelesuri.

Mihai Ralea's file contains a denunciation of his entire career and loyalties: he stood accused of having been a "socialist-communist" camouflaged within the PNT, of having revived the guilds so as to give the PCdR room for maneuver, and of having sponsored Soviet agents to protect himself in the event of a Soviet invasion.

One Siguranta record suggests that, in secret, Mihai Ralea was hoping to consolidate a left-wing opposition movement against Antonescu during the early months of 1941.

Mihai Ralea defended these, arguing that he had aimed at securing a protective deal between Romania and the Soviets, and that Carol had approved of his effort.

The explanation was viewed as plausible by police, and Mihai Ralea was allowed to go free.

Nevertheless, the file was reopened by August, after revelations that Mihai Ralea had cultivated communists since at least the 1930s.

Mihai Ralea was held there for about three months, to March 1943, and apparently enjoyed a mild detention regime, with visitations.

Mihai Ralea soon established contacts with the antifascist opposition, repeatedly seeking to set up a Peasantist left and rejoin the PNT.

Mihai Ralea was one of several literary critics who publicly chided a colleague, George Calinescu, for publishing a 1941 treatise which included racialist profiles of Romanian writers, alongside criticism of Ralea's own anti-nationalism.

Mihai Ralea appeared as a defense witness for Gheorghe Vladescu-Racoasa, an activist of the underground Union of Patriots.

Together with Hudita and other rival PNT-ists, and his friends in Iasi academia, Ralea signed to Grigore T Popa's manifesto of the intellectuals, demanding that Antonescu negotiate a separate peace with the Soviets.

Mihai Ralea reissued Viata Romaneasca with a similar statement about "the present triumph of our credo".

Meanwhile, keeping up with his earlier threats, Maniu repeatedly asked for Mihai Ralea to be indicted for war crimes.

Mihai Ralea played an instrumental part in the gradual installation of communism, and is described by various authors as the prototype "fellow traveler".

One of Iancu's essays, published by the Circle in January 1945, indicated that Mihai Ralea had always been right to highlight the social function of "aesthetic thinking", and as such had provided templates for a "moral therapy for this age".

Mihai Ralea's PST was drawn into the National Democratic Front coalition, which comprised the PCdR, the Ploughmen's Front, and the Union of Patriots.

In private, Mihai Ralea claimed that his alignment with the communists helped him provide for his large family, including former landowners, but his account is viewed as doubtful by Zavarache.

Mihai Ralea divulged this offer to the Soviet envoy, Andrey Vyshinsky.

Mihai Ralea was made Minister of Arts on March 6,1945, when Groza took the premiership from the deposed General Radescu.

In June 1945 Mihai Ralea was one of the rapporteurs at the Ploughmen's Front largest-ever General Congress.

Mihai Ralea became one of several intellectuals who were mobilized to run on the Ploughmen's Front list in the 1946 parliamentary election; he headlined the list for Falciu.

Around the same time, Mihai Ralea extended his personal protection to Serban Cioculescu, who became Iasi University professor in 1946 upon his intervention.

Mihai Ralea pursued his projects for workers' education, authorizing the establishment of a workers' theatrical troupe, Teatrul Muncitoresc CFR Giulesti.

In September 1946, Mihai Ralea stepped down from the Ministry of Arts, only to be appointed Ambassador to the United States.

Mihai Ralea was tasked with undermining the reputation of the anticommunist opposition and with popularizing communism among Romanian American exiles.

Mihai Ralea built a connection with the industrialist Nicolae Malaxa, but found vocal adversaries in Max Auschnitt and Richard Franasovici.

In 1948, Alan R McCracken from the Office of Special Operations argued that Ralea was Malaxa's political client, and had tipped Malaxa off about the planned nationalization of his industrial concern back in Romania.

American assistance fell below Mihai Ralea's expectations, owing to various factors, one of which was American suspicion that Groza was diverting food to relieve the Soviet famine; meanwhile, diaspora voices repeatedly argued that Mihai Ralea was playing down the scale of famine, and insinuated that he was embezzling funds.

When it transpired that Mihai Ralea was genuinely mistrusted by his American contacts, Groza reportedly asked another psychologist, the American-trained Nicolae Margineanu, to intervene directly and mend the relationship.

Mihai Ralea had appointed his mistress as cultural attache, but she deserted her post and left to Mexico while Ioana Mihai Ralea took up residence in the Romanian embassy.

Mihai Ralea was still the country's ambassador when King Michael I was forced to abdicate by the PCdR officials and a communized people's republic was proclaimed.

Mihai Ralea acted as a sponsor and liaison for Harry Fainaru, who was running a propaganda cell from Detroit.

Mihai Ralea was able to persuade Pauker not to recall him, and even organized a reception in her honor during October 1948; he organized a communist counter-manifestation upon Michael's arrival to Washington.

Mihai Ralea was again given the position of psychology chair at the University of Bucharest, and was made a member of the new Institute of History and Philosophy, whose president was Constantinescu-Iasi.

Mihai Ralea was seconded there by Constantin Ionescu Gulian, with whom he did research into the history of Romanian materialist philosophy.

Mihai Ralea prepared an anthropological tract, Explicarea omului.

Mihai Ralea responded to the pressures by presenting his services as an anti-American propagandist, making his first-hand experience in America into an irreplaceable asset; this assignment was inaugurated in January 1951, when Mihai Ralea and Gulian published in Studii a piece addressing the immorality of "American imperialists".

Mihai Ralea was again able to rescue Vianu, this time from communist persecution, and intervened to save the career of writer Costache Olareanu.

Mihai Ralea still had friendly contacts with his former supervisors in Foreign Affairs, though he complained to his peers that Pauker was snubbing him.

Mihai Ralea witnessed Pauker's 1952 downfall and banishment, and reputedly kept himself informed about her activities through mutual acquaintances.

Mihai Ralea's own survival in the post-Pauker era was an unusual feat.

Nevertheless, Mihai Ralea supported Gheorghiu-Dej's adoption of a national communist platform, which was presented as an alternative to Soviet control.

At the time, some Romanian anticommunist circles began taking an interest in Mihai Ralea, vainly hoping that he would be appointed premier of a post-Stalinist Romania.

In 1956, the psychology section became an independent Institute, and Mihai Ralea became its chairman.

Mihai Ralea was personally involved in securing ownership of its offices on Frumoasa Street, outside Calea Victoriei, previously held by the Comecom.

Also that year, Mihai Ralea published his historical essay on French politics and culture, Cele doua Frante.

Mihai Ralea was one of the select few Romanians, most of them trusted figures of the regime, who could reissue selections from their interwar literary contributions, at the specialized state company Editura de Stat pentru Literatura si Arta.

Mihai Ralea was one of the first in this series, with the 1957 Scrieri din trecut.

Mihai Ralea was active in reintegrating culturally some intellectuals who had been imprisoned and rehabilitated: together with one such figure, Constantin I Botez, he wrote the 1958 Istoria psihologiei.

Mihai Ralea carried on him a dossier on exile writer Vintila Horia, who had received the Prix Goncourt.

Mihai Ralea's mission was hampered by revelations about his own compromises with fascism, published in Le Monde, Paris-Presse and the Romanian diaspora press, under such titles as: "Mihai Ralea used to lift his arm really high".

Mihai Ralea's application was politely turned down, but he was honored with the vice presidency of the Great National Assembly Presidium and a seat on the republican Council of State.

In 1962, Mihai Ralea was one of the guest speakers at a Geneva conference on the generation gap, alongside Louis Armand, Claude Autant-Lara, and Jean Piaget.

Reportedly, Mihai Ralea excused Herseni's Iron Guard affiliation as a careerist move rather than a political crime.

Also heavy smoker, and prone to culinary excesses, Mihai Ralea checked himself in Otopeni hospital showing symptoms of facial nerve paralysis, with hypertension and fatigue.

Mihai Ralea died en route, on the morning of August 17,1964; officially, this occurred outside East Berlin, but, Slama-Cazacu notes, he was probably dead when the train was still crossing Czechoslovakia.

Mihai Ralea's body was transported back to Bucharest, and a day of mourning was observed nationally.

Mihai Ralea's final contribution in the press was a UNESCO-themed interview with Cristian Popisteanu, published by Lumea that same month.

Additionally, Mihai Ralea reduced aestheticism and social determinism to the basic units of "aesthetics" and "ethnicity".

Mihai Ralea believed that the origin of beauty was biological, before being human or social; he claimed that traditional society allowed no depiction of ugliness before the arrival of Christian art.

Mihai Ralea even sketched out his own relativist theory, according to which works of art could have limitless interpretations, thus unwittingly paralleling, or anticipating, the semiotics of Roland Barthes.

The solution, Mihai Ralea suggested, was for man to rediscover the simple joys of anonymity.

Mihai Ralea understood this as a natural development of Dimitrie Gusti's sociological "science of the nation", but better suited to the topic and more resourceful.

Mihai Ralea commended Ion Luca Caragiale, the creator of modern Romanian humor, as the voice of lucidity, equating irony with intelligence.

Mihai Ralea extended this vision in analyzing humorous poems by his friend George Topirceanu, arguing that good comedy required both a philosophical and a lyrical attitude.

Mihai Ralea did have his uncertainties about the grounding of his own idea.

Mihai Ralea contended that the grand epic genre, unlike the short story, did not yet suit the Romanian psyche, since it required discipline, anonymity, and a "great moral significance".

Mihai Ralea postulated a deterministic relationship between the staples of ancestral Romanian folklore and modern literary choices: in the absence of any ambitious poetic cycles, Romanian ballads and doine had naturally mutated into novellas.

However, according to political scientist Ioan Stanomir, Mihai Ralea's discourse is to be read as a "celebration of slavery".

Around 1950, Mihai Ralea was studying Marxist aesthetics and Marxist literary criticism, advising young literati, and his colleague Vianu, to do the same.

Mihai Ralea was going back on his cosmopolitanism, seeing it as an obstacle to the proper understanding of Romanian society.

Mihai Ralea's teaching aid for social psychology was similarly adjusted, introducing chapters on "class psychology", though, as Zavarache argues, these modifications were "surprisingly kept to a minimum".

Especially in his reedited Scrieri din trecut, Mihai Ralea sought to reconcile Ibraileanu's social Darwinism with the official readings of Marxism, as well as with Michurinism and Pavlovianism.

Mihai Ralea finds some of Ralea's conclusions, including his critique of vitalism as the intellectual source of fascism, to be on par with those of Jean-Paul Sartre.

Mihai Ralea maintained that remedial sanctions were a characteristic of modern civilized society, and that the social fact of "success" was created within that setting.

Nevertheless, some members of this intellectual school, such as Adrian Marino and Matei Calinescu, continued to draw inspiration from Mihai Ralea, having rediscovered his early Bergsonian essays.

From within the anti-communist movement, Mihai Ralea was defended by author Nicolae Steinhardt.

The Husi library, named after Mihai Ralea, has been hosting the entire corpus of his works since 2013.