1.

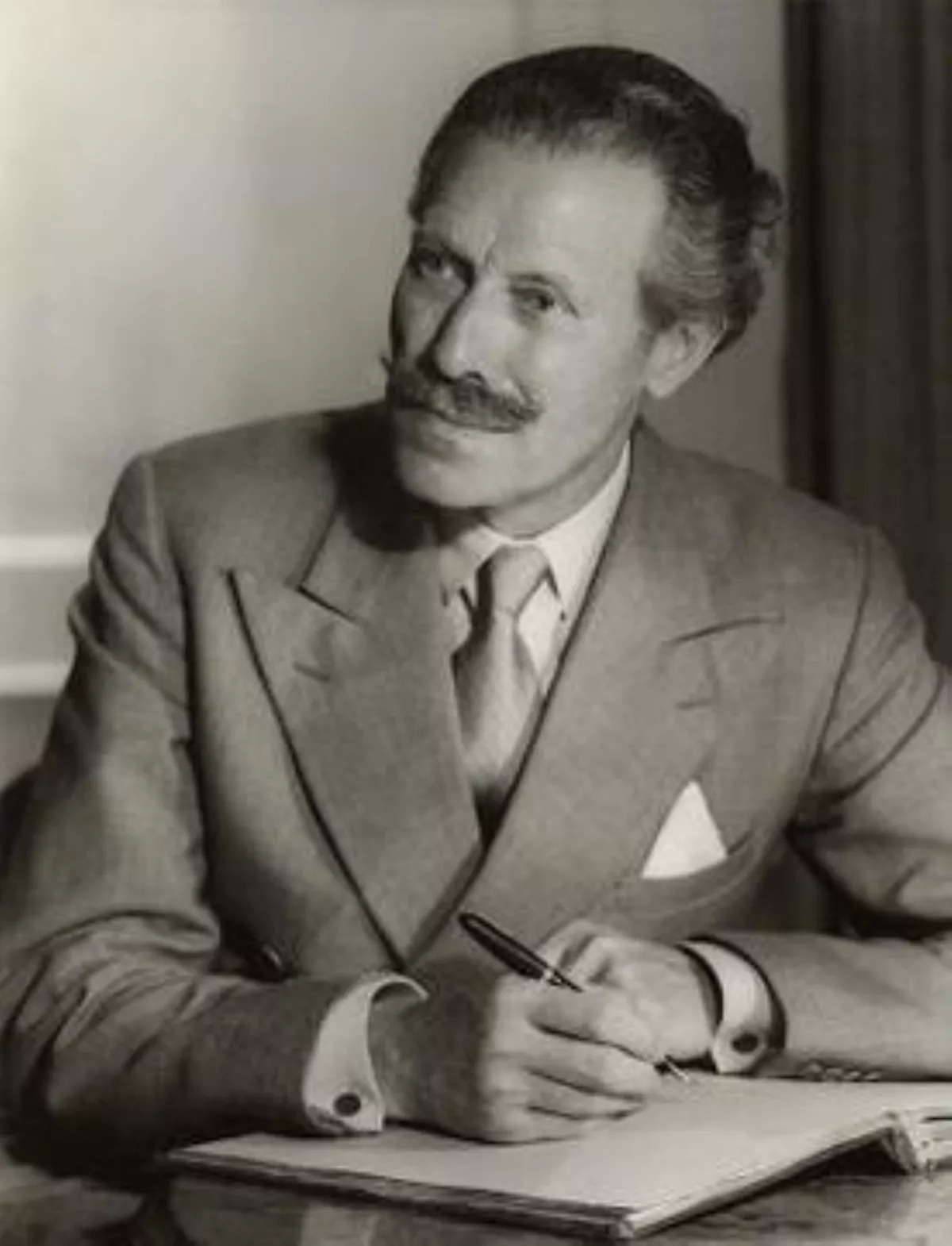

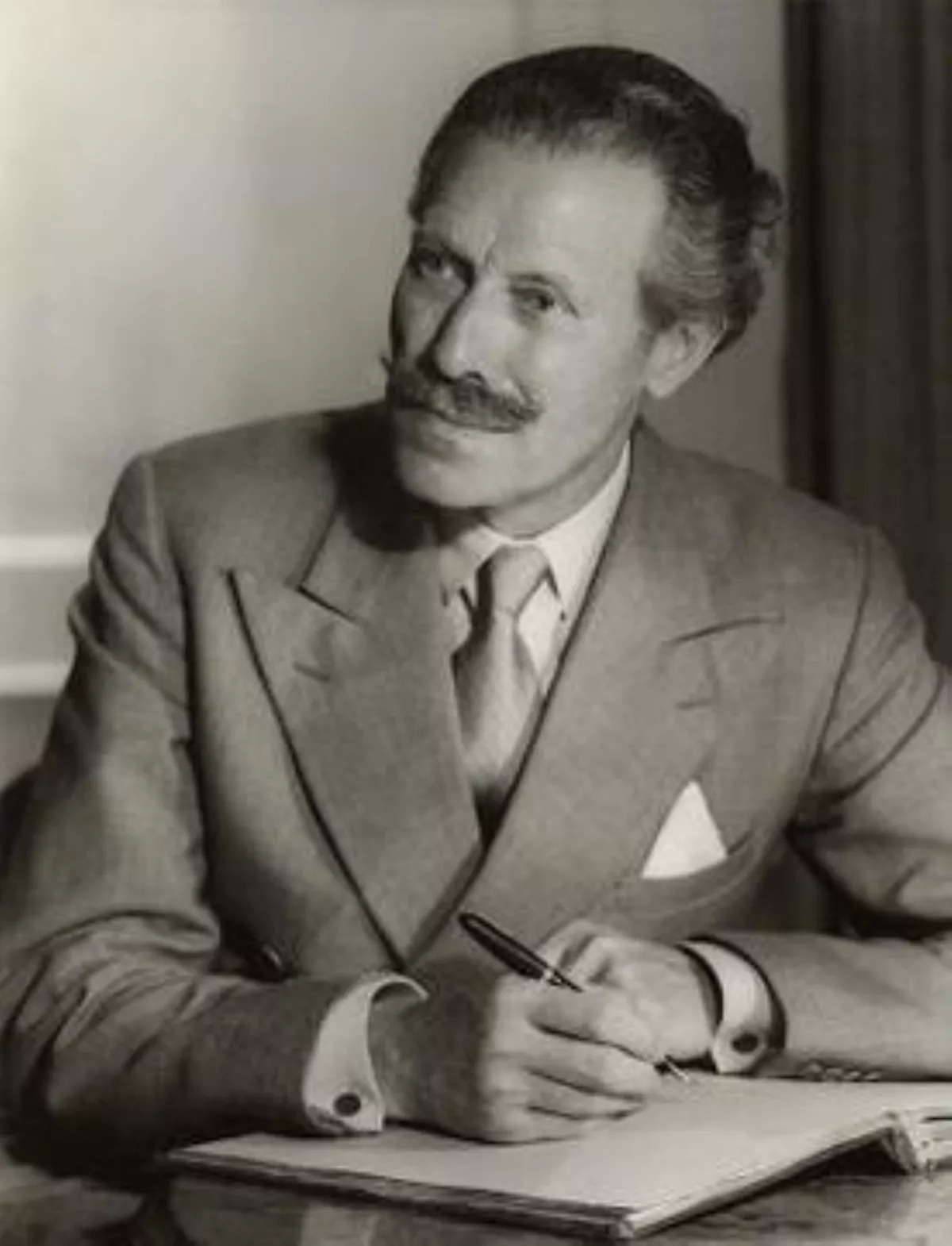

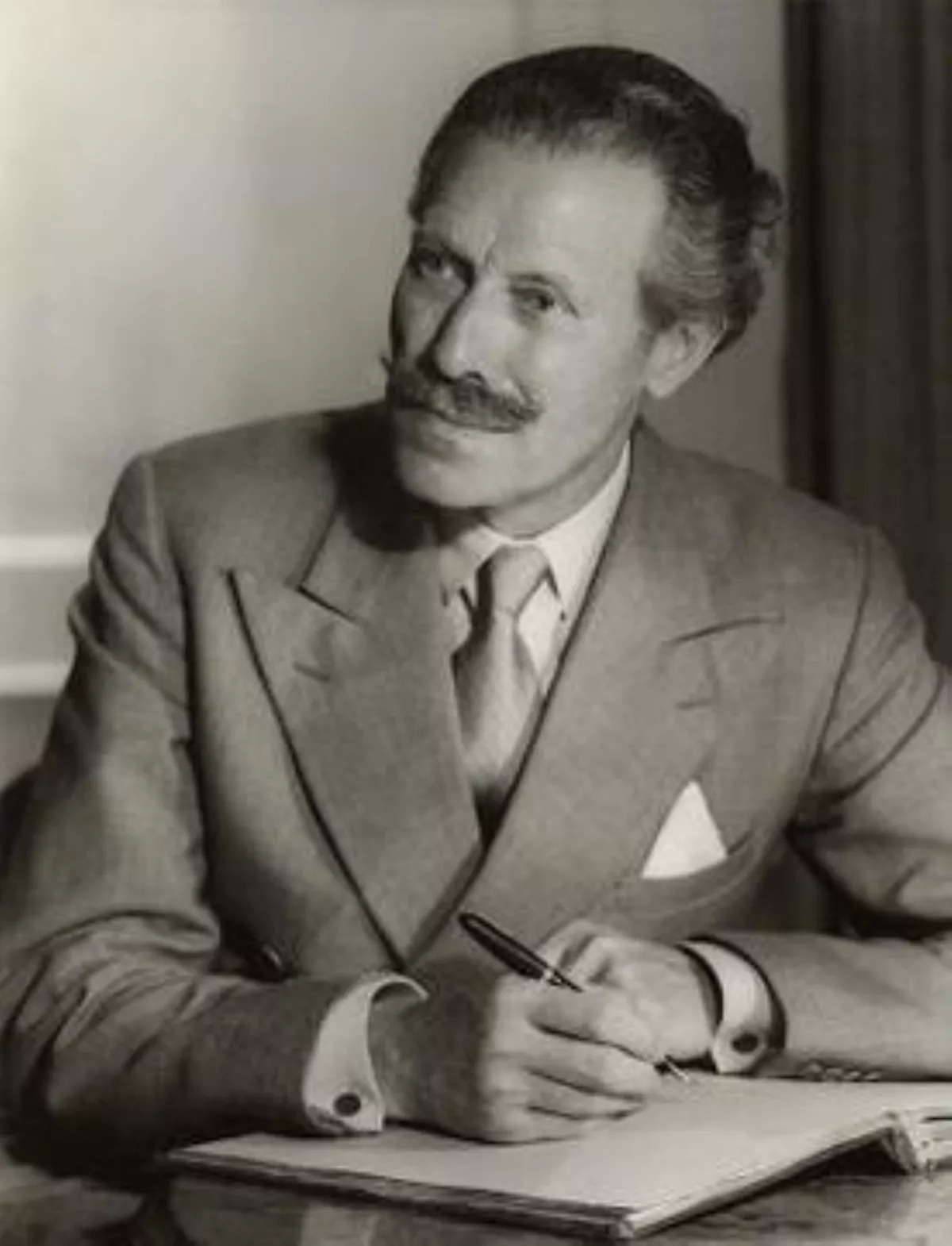

1. Mortimer Wheeler is recognised as one of the most important British archaeologists of the 20th century, responsible for successfully encouraging British public interest in the discipline and advancing methodologies of excavation and recording.

1.

1. Mortimer Wheeler is recognised as one of the most important British archaeologists of the 20th century, responsible for successfully encouraging British public interest in the discipline and advancing methodologies of excavation and recording.

Mortimer Wheeler was born on 10 September 1890 in the city of Glasgow, Scotland.

Mortimer Wheeler was the first child of the journalist Robert Mortimer Wheeler and his second wife Emily Wheeler.

When Mortimer Wheeler was four, his father was appointed chief leader writer for the Bradford Observer.

Mortimer Wheeler was inspired by the moors surrounding Saltaire and fascinated by the area's archaeology.

Mortimer Wheeler later wrote about discovering a late prehistoric cup-marked stone, searching for lithics on Ilkley Moor, and digging into a barrow on Baildon Moor.

Mortimer Wheeler remained emotionally distant from his mother, instead being far closer to his father, whose company he favoured over that of other children.

Mortimer Wheeler's father had a keen interest in natural history and a love of fishing and shooting, rural pursuits in which he encouraged Mortimer to take part.

Robert acquired many books for his son, particularly on the subject of art history, with Mortimer Wheeler loving to both read and paint.

In 1899, Mortimer Wheeler joined Bradford Grammar School shortly before his ninth birthday, where he proceeded straight to the second form.

In 1902, Robert and Emily had a second daughter, whom they named Betty; Mortimer Wheeler showed little interest in this younger sister.

Rather than being sent for a conventional education, when he was 15 Mortimer Wheeler was instructed to educate himself by spending time in London, where he frequented the National Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Mortimer Wheeler began studying for a Master of Arts degree in classical studies, which he attained in 1912.

Mortimer Wheeler's proposed project had been to analyse Romano-Rhenish pottery, and with the grant he funded a trip to the Rhineland in Germany, there studying the Roman pottery housed in local museums; his research into this subject was never published.

Michael Mortimer Wheeler was their only child, something that was a social anomaly at the time, although it is unknown whether or not this was by choice.

In May 1915, Mortimer Wheeler transferred to the 1st Lowland Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery, and was confirmed in his rank on 1 July, with a promotion to temporary lieutenant from the same date.

In October 1917 Mortimer Wheeler was posted to the 76th Army Field Artillery Brigade, one of the Royal Field Artillery brigades under the direct control of the General Officer Commanding, Third Army.

Mortimer Wheeler was part of the Left Group of artillery covering the advancing Allied infantry in the battle.

Mortimer Wheeler returned for two six-horse teams, and under heavy fire, in full view of the enemy, successfully brought back both guns to his battery position and turned them on the enemy.

Mortimer Wheeler continued as part of the British forces pushing westward until the German surrender in November 1918, receiving a mention in dispatches on 8 November.

Mortimer Wheeler was not demobilised for several months, instead being stationed at Pulheim in Germany until March; during this time he wrote up his earlier research on Romano-Rhenish pottery, making use of access to local museums, before returning to London in July 1919.

On returning to London, Mortimer Wheeler moved into a top-floor flat near Gordon Square with his wife and child.

Mortimer Wheeler returned to working for the Royal Commission, examining and cataloguing the historic structures of Essex.

Mortimer Wheeler soon followed this with two papers in the Journal of Roman Studies; the first offered a wider analysis of Roman Colchester, while the latter outlined his discovery of the vaulting for the city's Temple of Claudius which was destroyed by Boudica's revolt.

Mortimer Wheeler then submitted his research on Romano-Rhenish pots to the University of London, on the basis of which he was awarded his Doctorate of Letters; thenceforth until his knighthood he styled himself as Dr Wheeler.

Mortimer Wheeler was unsatisfied with his job in the commission, unhappy that he was receiving less pay and a lower status than he had had in the army, so began to seek alternative employment.

Mortimer Wheeler obtained a post as the Keeper of Archaeology at the National Museum of Wales, a job that entailed becoming a lecturer in archaeology at the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire.

Mortimer Wheeler recognised that Wales was very divided regionally, with many Welsh people having little loyalty to Cardiff; thus, he made a point of touring the country, lecturing to local societies about archaeology.

Mortimer Wheeler was impatient to start excavations, and in July 1921 started a six-week project to excavate at the Roman fort of Segontium; accompanied by his wife, he used up his holiday to oversee the project.

Mortimer Wheeler was keen on training new generations of archaeologists, and two of the most prominent students to excavate with him at Segontium were Victor Nash-Williams and Ian Richmond.

Mortimer Wheeler published the results of his excavation in The Roman Fort Near Brecon.

Mortimer Wheeler then employed a close friend, Cyril Fox, to take on the vacated position of Keeper of Archaeology.

Mortimer Wheeler's proposed reforms included extending the institution's reach and influence throughout Wales by building affiliations with regional museums, and focusing on fundraising to finance the completion of the new museum premises.

Mortimer Wheeler had been considering a return to London for some time and eagerly agreed, taking on the post, which was based at Lancaster House in the St James's area, in July 1926.

In Wales, many felt that Mortimer Wheeler had simply taken the directorship of the National Museum to advance his own career prospects, and that he had abandoned them when a better offer came along.

Mortimer Wheeler himself disagreed, believing that he had left Fox at the Museum as his obvious successor, and that the reforms he had implemented would therefore continue.

Mortimer Wheeler expressed his opinion that the museum "had to be cleaned, expurgated, and catalogued; in general, turned from a junk shop into a tolerably rational institution".

In 1930, Mortimer Wheeler persuaded them to increase that budget, as he highlighted increasing visitor numbers, publications, and acquisitions, as well as a rise in the number of educational projects.

Also involved in the largely moribund Royal Archaeological Institute, Mortimer Wheeler organised its relocation to Lancaster House.

In 1927, Mortimer Wheeler took on an unpaid lectureship at University College London, where he established a graduate diploma course on archaeology; one of the first to enroll was Stuart Piggott.

In 1928, Mortimer Wheeler curated an exhibit at UCL on "Recent Work in British Archaeology", for which he attracted much press attention.

Mortimer Wheeler was keen to continue archaeological fieldwork outside London, undertaking excavations every year from 1926 to 1939.

Mortimer Wheeler enjoyed the opportunity to excavate at a civilian as opposed to military site, and liked its proximity to his home in London.

Mortimer Wheeler was particularly interested in searching for a pre-Roman Iron Age oppidum at the site, noting that the existence of a nearby Catuvellauni settlement was attested to in both classical texts and numismatic evidence.

The report resulted in the first major published criticism of Mortimer Wheeler, produced by the young archaeologist Nowell Myres in a review for Antiquity; although stating that there was much to praise about the work, he critiqued Mortimer Wheeler's selective excavation, dubious dating, and guesswork.

Mortimer Wheeler responded with a piece in which he defended his work and launched a personal attack on both Myres and Myres's employer, Christ Church, Oxford.

Mortimer Wheeler had long desired to establish an academic institution devoted to archaeology that could be based in London.

Mortimer Wheeler hoped that it could become a centre in which to establish the professionalisation of archaeology as a discipline, with systematic training of students in methodological techniques of excavation and conservation and recognised professional standards; in his words, he hoped "to convert archaeology into a discipline worthy of that name in all senses".

Mortimer Wheeler further described his intention that the Institute should become "a laboratory: a laboratory of archaeological science".

Mortimer Wheeler was later able to persuade the University of London, a federation of institutions across the capital, to support the venture, and both he and Tessa began raising funds from wealthy backers.

Mortimer Wheeler was keen to emphasise that his workforce consisted of many young people as well as both men and women, thus presenting the image of archaeology as a modern and advanced discipline.

The report's publication allowed further criticism to be voiced of Wheeler's approach and interpretations; in his review of the book, the archaeologist W F Grimes criticised the highly selective nature of the excavation, noting that Wheeler had not asked questions regarding the socio-economic issues of the community at Maiden Castle, aspects of past societies that had come to be of increasing interest to British archaeology.

In 1936, Mortimer Wheeler embarked on a visit to the Near East, sailing from Marseille to Port Said, where he visited the Old Kingdom tombs of Sakkara.

Mortimer Wheeler was away for six weeks, and upon his return to Europe discovered that his wife Tessa had died of a pulmonary embolism after a minor operation on her toe.

Mortimer Wheeler had become President of the Museums Association, and in a presidential address given in Belfast talked on the topic of preserving museum collections in wartime, believing that Britain's involvement in a second European conflict was imminent.

Mortimer Wheeler was awarded an honorary doctorate from Bristol University, and at the award ceremony met the Conservative Party politician Winston Churchill, who was then engaged in writing his multi-volume A History of the English-Speaking Peoples; Churchill asked Wheeler to help him in writing about late prehistoric and early medieval Britain, to which Wheeler agreed.

Mortimer Wheeler had been expecting and openly hoping for war with Nazi Germany for a year before the outbreak of hostilities; he believed that the United Kingdom's involvement in the conflict would remedy the shame that he thought had been brought upon the country by its signing of the Munich Agreement in September 1938.

Mortimer Wheeler was assigned to assemble the 48th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery at Enfield, where he set about recruiting volunteers, including his son Michael.

In 1941 Mortimer Wheeler was awarded a Fellowship of the British Academy.

Mavis de Vere Cole - Mortimer Wheeler's wife, had meanwhile entered into an affair with a man named Clive Entwistle, who lambasted Mortimer Wheeler as "that whiskered baboon".

When Mortimer Wheeler discovered Entwistle in bed with her, he initiated divorce proceedings that were finalised in March 1942.

Mortimer Wheeler was part of the Allied counter-push, taking part in the Second Battle of El Alamein and the advance on Axis-held Tripoli.

Mortimer Wheeler left Italy in November 1943 and returned to London.

Mortimer Wheeler resigned as director of the Society of Antiquaries, but was appointed the group's representative to the newly formed Council for British Archaeology.

Mortimer Wheeler developed a relationship with a woman named Kim Collingridge, and asked her to marry him.

Mortimer Wheeler then set sail for Bombay aboard a transport ship, the City of Exeter, in February 1944.

Mortimer Wheeler had been suggested for the job by Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy of India, who had been acting on the recommendations of the archaeologist Leonard Woolley, who had written a report lamenting the state of the archaeological establishment in the British-controlled subcontinent.

Mortimer Wheeler recognised this state of affairs, in a letter to a friend complaining about the lack of finances and equipment, commenting that "We're back in 1850".

Mortimer Wheeler then toured the subcontinent, seeking to meet all of the Survey's staff members.

Mortimer Wheeler had drawn up a prospectus containing research questions that he wanted the Survey to focus on; these included understanding the period between the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilization and the Achaemenid Empire, discerning the socio-cultural background to the Vedas, dating the Aryan invasion, and establishing a dating system for southern India before the 6th century CE.

Lal, later commenting that "behind the gruff exterior, Sir Mortimer Wheeler had a very kind and sympathetic heart".

Mortimer Wheeler later led a more detailed excavation at Harappa, where he exposed further fortifications and established a stratigraphy for the settlement.

The excavation had been plagued by severe rains and tropical heat, although it was during the excavation that World War II ended; in celebration, Mortimer Wheeler gave all his workers an extra rupee for the day.

Mortimer Wheeler later undertook excavations of six megalithic tombs in Brahmagiri, Mysore, which enabled him to gain a chronology for the archaeology of much of southern India.

Mortimer Wheeler established a new archaeological journal, Ancient India, planning for it to be published twice a year.

Mortimer Wheeler had trouble securing printing paper and faced various delays; the first issue was released in January 1946, and he would release three further volumes during his stay.

Mortimer Wheeler married Kim Collingridge in Simla, before he and his wife took part in an Indian Cultural Mission to Iran.

Mortimer Wheeler enjoyed the trip, and was envious of Tehran's archaeological museum and library, which was far in advance of anything then found in India.

Mortimer Wheeler was present during the 1947 Partition of India into the Dominion of Pakistan and the Union of India and the accompanying ethnic violence between Hindu and Muslim communities.

Mortimer Wheeler was unhappy with how these events had affected the Archaeological Survey, complaining that some of his finest students and staff were now citizens of Pakistan and no longer able to work for him.

Mortimer Wheeler was based in New Delhi when the city was rocked by sectarian violence, and attempted to help many of his Muslim staff members escape from the Hindu-majority city unharmed.

Mortimer Wheeler further helped smuggle Muslim families out of the city hospital, where they had taken refuge from a violent Hindu mob.

Mortimer Wheeler was awarded the Territorial Decoration in September 1956.

Crawford, resigned from the Society in protest, deeming Mortimer Wheeler to have been a far more appropriate candidate for the position.

Mortimer Wheeler nevertheless disliked the country, and in later life exhibited anti-Americanism.

Mortimer Wheeler spent three months in the Dominion of Pakistan during early 1949, where he was engaged in organising the fledgling Pakistani Archaeological Department with the aid of former members of the Archaeological Survey and new students whom he recruited.

Mortimer Wheeler himself was appointed the first President of the Pakistani Museums Association, and found himself as a mediator in the arguments between India and Pakistan over the redistribution of archaeological and historic artefacts following the partition.

Mortimer Wheeler wrote a work of archaeological propaganda for the newly formed state, Five Thousand Years of Pakistan.

Mortimer Wheeler had been keen to return to excavation in Britain.

Mortimer Wheeler was invited by the Ancient Monuments Department of the Ministry of Works to excavate the Stanwick Iron Age Fortifications in North Riding, Yorkshire, which he proceeded to do over the summers of 1951 and 1952.

In 1949, Wheeler was appointed Honorary Secretary of the British Academy after Frederic G Kenyon stepped down from the position.

In doing so, Piggott stated, Mortimer Wheeler helped rid the society of its "self-perpetuating gerontocracy".

In 1956, Mortimer Wheeler retired from his part-time professorship at the Institute of Archaeology.

Childe was retiring from his position of director that year, and Mortimer Wheeler involved himself in the arguments surrounding who should replace him.

That year, Mortimer Wheeler's marriage broke down, and he moved from his wife's house to a former brothel at 27 Whitcomb Street in central London.

In December 1963, Mortimer Wheeler underwent a prostate operation that went wrong, and was hospitalised for over a month.

In November 1967, Mortimer Wheeler became a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour, and in 1968 he became a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Mortimer Wheeler became famous in Britain as "the embodiment of popular archaeology through the medium of television".

Mortimer Wheeler is alleged to have prepared for the show by checking beforehand which objects had been temporarily removed from display.

Mortimer Wheeler appeared in an episode of Buried Treasure, an archaeology show hosted by Daniel, in which the pair travelled to Denmark to discuss Tollund Man.

From 1954 onward, Mortimer Wheeler began to devote an increasing amount of his time to encouraging greater public interest in archaeology, and it was in that year that he obtained an agent.

In 1955 Mortimer Wheeler released his episodic autobiography, Still Digging, which had sold over 70,000 copies by the end of the year.

In 1959, Mortimer Wheeler wrote Early India and Pakistan, which was published as part as Daniel's "Ancient Peoples and Places" series for Thames and Hudson; as with many earlier books, he was criticised for rushing to conclusions.

Mortimer Wheeler wrote the section entitled "Ancient India" for Piggott's edited volume The Dawn of Civilisation, which was published by Thames and Hudson in 1961, before writing an introduction for Roger Wood's photography book Roman Africa in Colour, which was published by Thames and Hudson.

Mortimer Wheeler then agreed to edit a series for the publisher, known as "New Aspects of Antiquity", through which they released a variety of archaeological works.

Swan invited Mortimer Wheeler to provide lectures on the archaeology of ancient Greece aboard their Hellenic cruise line, which he did in 1955.

Mortimer Wheeler had continued his archaeological investigations, and in 1954 led an expedition to the Somme and Pas de Calais where he sought to obtain more information on the French Iron Age to supplement that gathered in the late 1930s.

Mortimer Wheeler agreed to sit as Chairman of the Archaeological Committee overseeing excavations at York Minster, work which occupied him into the 1970s.

Mortimer Wheeler had continued his work with museums, campaigning for greater state funding for them.

Mortimer Wheeler developed personal relationships with various employees at the British Treasury, and offered the academy's services as an intermediary in dealing with the Egypt Exploration Society, the British School at Athens, the British School at Rome, the British School at Ankara, the British School in Iraq, and the British School at Jerusalem, all of which were then directly funded independently by the Treasury.

Meanwhile, Mortimer Wheeler had been campaigning for the establishment of a British Institute of Persian Studies, a project which was supported by the British Embassy in Tehran; they hoped that it would rival the successful French Institute in the city.

Mortimer Wheeler further campaigned for the establishment of a British Institute in Japan, although these ideas were scrapped amid the British financial crisis of 1967.

Mortimer Wheeler retained an active interest in the running of these British institutions abroad; in 1967 he visited the British School in Jerusalem amid the Six-Day War between Israel and its Arab neighbours, and in January 1968 visited the Persian institute with the archaeologist Max Mallowan and Mallowan's wife Agatha Christie, there inspecting the excavations at Siraf.

Mortimer Wheeler attended the event, whose conference proceedings were published as a festschrift for the octogenarian.

In spring 1973, Mortimer Wheeler returned to BBC television for two episodes of the archaeology-themed series Chronicle in which he discussed his life and career.

The episodes were well received, and Mortimer Wheeler became a close friend of the show's producer, David Collison.

Mortimer Wheeler divided opinion among those who knew him, with some loving and others despising him, and during his lifetime, he was often criticised on both scholarly and moral grounds.

Mortimer Wheeler was meticulous in his writings, and would repeatedly revise and rewrite both pieces for publication and personal letters.

Mortimer Wheeler expressed the view that he was "the least political of mortals".

Mortimer Wheeler expressed little interest in his relatives; in later life, he saw no reason to have a social relationship with people purely on the basis of family ties.

In 1945, Mortimer Wheeler married his third wife, Margaret Collingridge.

Meanwhile, Mortimer Wheeler was well known for his conspicuous promiscuity, favouring young women for one-night stands, many of whom were his students.

Mortimer Wheeler developed powers of command and creative administration that brought him extraordinary successes in energising feeble institutions and creating new ones.

Mortimer Wheeler has been termed "the most famous British archaeologist of the twentieth century" by archaeologists Gabriel Moshenska and Tim Schadla-Hall.

Chakrabarti stated that Mortimer Wheeler had contributed to South Asian archaeology in various ways: by establishing a "total view" of the region's development from the Palaeolithic onward, by introducing new archaeological techniques and methodologies to the subcontinent, and by encouraging Indian universities to begin archaeological research.

However, writing in 2011, Moshenska and Schadla-Hall asserted that Mortimer Wheeler's reputation has not undergone significant revision among archaeologists, but that instead he had come to be remembered as "a cartoonish and slightly eccentric figure" whom they termed "Naughty Morty".

In 1992 and again in 2001, Mortimer Wheeler Lectures were keynote presentations in British Academy archaeological conferences.

Hawkes admitted she had developed "a very great liking" for Mortimer Wheeler, having first met him when she was an archaeology student at the University of Cambridge.

Mortimer Wheeler believed that he had "a daemonic energy", with his accomplishments in India being "almost superhuman".