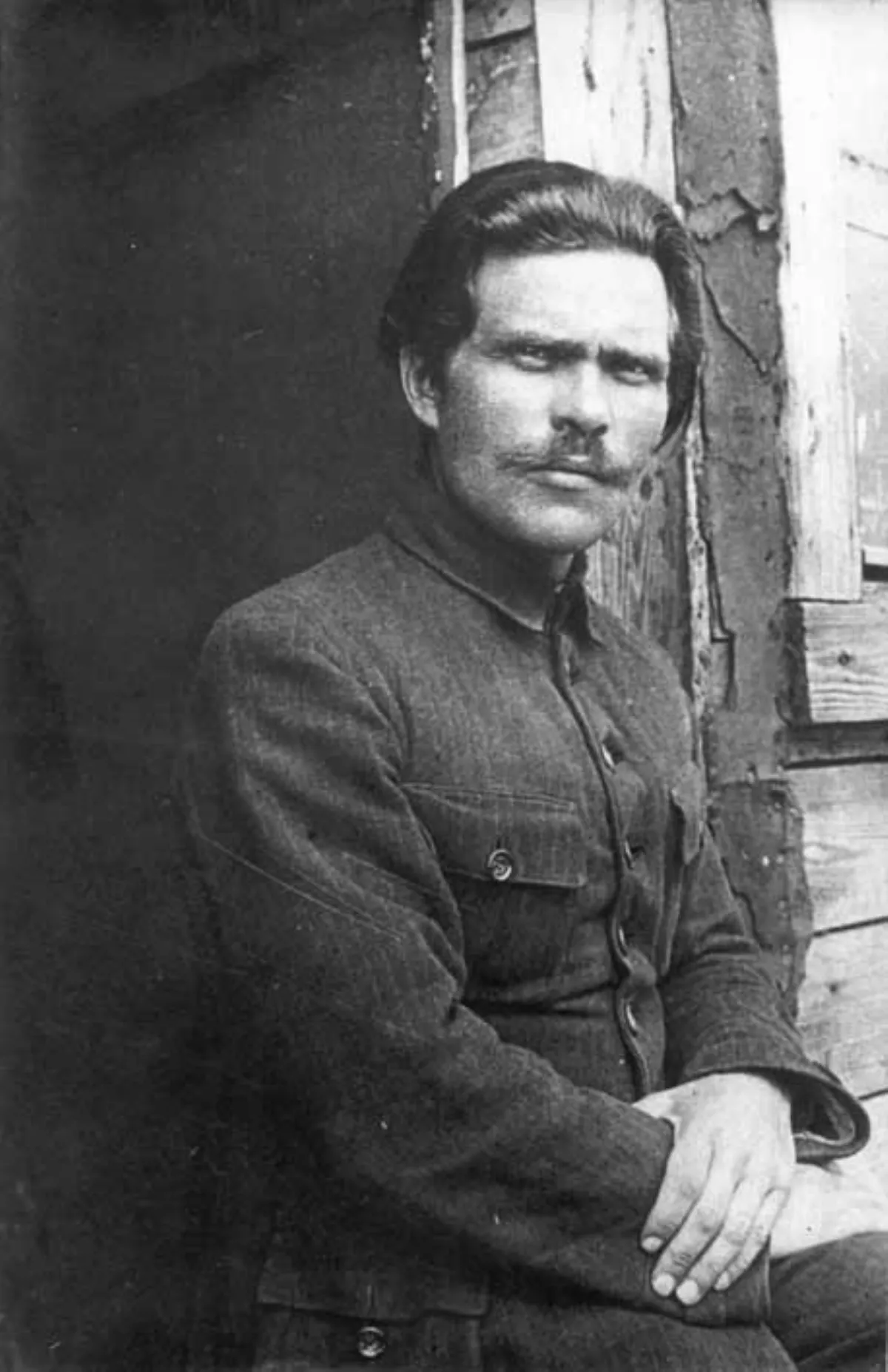

1.

1. Nestor Makhno established the Makhnovshchina, a mass movement by the Ukrainian peasantry to establish anarchist communism in the country between 1918 and 1921.

1.

1. Nestor Makhno established the Makhnovshchina, a mass movement by the Ukrainian peasantry to establish anarchist communism in the country between 1918 and 1921.

Nestor Makhno rallied Bolshevik support to lead an insurgency, defeating the Central Powers' occupation forces at the Battle of Dibrivka and establishing the Makhnovshchina.

Nestor Makhno rebuilt his army from the remains of Nykyfor Hryhoriv's forces in western Ukraine, routed the White Army at the Battle of Perehonivka, and captured most of southern and eastern Ukraine, where they again attempted to establish anarchist communism.

The Bolsheviks immediately turned on Nestor Makhno, wounding him and driving him westward in August 1921 to Romanian concentration camps, Poland, and Europe, before he settled in Paris with his wife and daughter.

Nestor Makhno wrote memoirs and articles for radical newspapers, playing a role in the development of platformism.

Nestor Makhno's family continued to be persecuted in the decades following his death of tuberculosis at the age of 45.

Nestor Makhno was the youngest of five children born to Ivan and Evdokia Mikhnenko, former serfs who had been emancipated in 1861.

Nestor Makhno's father died when Nestor was only ten months old, leaving behind his impoverished family.

Nestor Makhno was briefly fostered by a more well-off peasant couple, but he was unhappy with them and returned to his family of birth.

Nestor Makhno started to attend a local secular school when he turned eight years old.

Nestor Makhno was a good student at first but grew to skip school to play games and ice skate.

Nestor Makhno worked at a local estate in the summer after his first school year.

Nestor Makhno's brothers worked as farmhands to support the family.

Nestor Makhno attended one more year of school before his family's extreme poverty forced the ten-year-old to work the fields full-time, which led Nestor Makhno to develop a "sort of rage, resentment, even hatred for the wealthy property-owner".

Nestor Makhno quickly alerted an older stable hand Bat'ko Ivan, who attacked the assailants and led a spontaneous workers' revolt against the landlord.

Nestor Makhno rapidly moved between jobs, focusing most of his work on his mother's land, while occasionally returning to employment to help provide for his brothers.

Nestor Makhno distributed propaganda for the Social Democratic Labor Party before affiliating with his home town's local anarchist communist group, the Union of Poor Peasants.

Nestor Makhno was initially distrusted by other members of the group due to his apparent penchant for drinking and getting into fights.

On 26 March 1910, a Katerynoslav district court-martial sentenced Nestor Makhno to be hanged.

Nestor Makhno was moved several times: to the Luhansk prison, where family briefly visited him, to the Katerynoslav prison, and in August 1911, to Butyrka prison in Moscow, where over 3,000 political prisoners were being held.

Nestor Makhno's frequent boasting in prison earned him the nickname "Modest".

Nestor Makhno spent many periods in the prison hospital throughout his sentence.

In Butyrka prison, Nestor Makhno met the anarchist communist politician Peter Arshinov, who took the young anarchist on as a student.

Nestor Makhno became disillusioned with intellectualism during this time after seeing the prejudice with which guards treated prisoners of different social classes.

Prison did not break his desire for revolution, as Nestor Makhno swore that he would "contribute to the free re-birth of his country".

When political prisoners were released during the February Revolution of 1917, Nestor Makhno's shackles were removed for the first time in eight years.

Nestor Makhno found himself physically off-balance without the chains weighing him down and in need of sunglasses after years in dark prison cells.

In March 1917, the 28-year-old Nestor Makhno returned to Huliaipole, where he was reunited with his mother and elder brothers.

Nestor Makhno met Nastia Vasetskaia, who would become his first wife, during this period but his activism left little time for his marriage.

Nestor Makhno quickly became a leading figure in Huliaipole's revolutionary movement, sidelining any political parties that sought to control the workers' organizations.

Nestor Makhno justified his leadership as only a temporary responsibility.

Nestor Makhno criticized the movement for largely dedicating itself to propaganda activities.

Nestor Makhno called for disarming the local bourgeoisie, expropriating their property, and bringing all private enterprise under workers' control.

Nestor Makhno dispatched his brother Savelii to Oleksandrivsk at the head of an armed anarchist detachment to assist the Bolsheviks in retaking the city from the Nationalists.

The city was taken and Nestor Makhno was chosen as the anarchists' representative to the Oleksandrivsk Revolutionary Committee.

Nestor Makhno was elected chairman of a commission, which reviewed the cases of accused counter-revolutionary military prisoners, and oversaw the release of still imprisoned workers and peasants.

Nestor Makhno thereafter returned to Huliaipole, where he organized the town bank's expropriation to fund the local anarchist movement's revolutionary activities.

Nestor Makhno was personally summoned to the train of Bolshevik Commander Alexander Yegorov but failed to link up with Yegorov who was in fast retreat.

Unable to return home, Nestor Makhno retreated to Taganrog, where he held a conference of Huliaipole's exiled anarchists.

Nestor Makhno left to rally Russian support for the Ukrainian anarchist cause with plans to retake Huliaipole in July 1918.

Nestor Makhno pejoratively dubbed the city "the capital of the paper revolution" after its local anarchist intellectuals, whom Makhno considered more inclined to slogans and manifestos than action.

Nestor Makhno met the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, who at this time were beginning to turn against the Bolsheviks.

Satisfied with his time in Moscow, Nestor Makhno applied to the Kremlin for forged identity papers so that he could cross the Ukrainian border.

Yakov Sverdlov immediately arranged for Nestor Makhno to meet Vladimir Lenin, who believed that anarchism had "contaminated" the peasantry and questioned Nestor Makhno extensively.

Nestor Makhno staunchly defended the Ukrainian anarchist movement from charges of "counter-revolution", criticizing the Red Guards for sticking to the railways while peasant partisans fought on the front lines.

Lenin expressed his admiration for Nestor Makhno and admitted he had made mistakes in his analysis of the revolutionary conditions in Ukraine, where anarchists had already become the predominant revolutionary force.

Nestor Makhno finally departed for the border in late June 1918, content that he had taken "the temperature of the revolution".

Nestor Makhno learned that the forces occupying Huliaipole had shot, tortured, and arrested many of the town's revolutionaries.

Nestor Makhno himself was forced to take precautions to evade capture.

Nestor Makhno advocated coordinated attacks on the estates of large landowners, advised against individual acts of terrorism, and forbade anti-semitic pogroms.

In Ternivka, Nestor Makhno revealed himself to the local population and established a peasant detachment to lead attacks against the occupation and Hetmanate government.

In coordination with partisans in Rozhdestvenka, Nestor Makhno resolved to reoccupy and establish Huliaipole as the insurgency's permanent headquarters.

Nestor Makhno raided Austrian positions, seizing weapons and money, which led to the insurrection's intensification in the region.

Nestor Makhno's detachment withdrew north, where it sought refuge in the Dibrivka forest, neighboring the village of Velykomykhailivka.

Nestor Makhno, in turn, led a campaign of retributive attacks against the occupation forces and their collaborators, including much of the region's Mennonite population.

Nestor Makhno focused much of his energies on agitating among the peasantry, gathering much support in the region through impassioned impromptu village speeches against his enemies.

At a regional insurgent conference, Nestor Makhno proposed that they open up a war on four simultaneous fronts against the Hetmanate, Central Powers, Don Cossacks, and nascent White movement.

Nestor Makhno argued that to prosecute such a conflict, it would be necessary to organize a Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine according to a federal model, directly answerable to him as commander-in-chief.

The next month, Nestor Makhno extricated himself from the front to attend the movement's second regional congress in Huliaipole.

Nestor Makhno was elected honorary chairman, but rejected official chairmanship as the front required his attention.

Nestor Makhno justified the integration of the insurgent forces into the Red Army as a matter of placing the "revolution's interests above ideological differences".

Nestor Makhno was, nevertheless, open about his contempt for the new order of political commissars.

Bolshevik interference in front-line operations even led to Nestor Makhno arresting a Cheka detachment, which had directly obstructed his command.

Kamenev immediately published an open letter to Nestor Makhno, praising him as an "honest and courageous fighter" in the war against the White movement.

Kamenev of the Politburo telegrammed Nestor Makhno to condemn Hryhoriv or else face a declaration of war.

Nestor Makhno relinquished command of the 7th Ukrainian Soviet Division and declared his intention to wage a guerrilla war against the Whites from the rear.

In early July 1919, Nestor Makhno fell back into Kherson province, where he met with Hryhoriv's green army.

Red Army mutinies became so bad that the Ukrainian Bolshevik leader Nikolai Golubenko even telephoned Nestor Makhno, begging him to subordinate himself again to Bolshevik command, which Nestor Makhno refused.

The insurgents launched several effective attacks behind White lines, Nestor Makhno himself commanding a cavalry assault against Mykolaivka that resulted in the capture of sorely needed munitions.

Nestor Makhno led the pursuit of the retreating Whites, decisively routing the enemy forces.

Nestor Makhno quickly ordered the revolutionary committee be shut down and forbade their activities under penalty of death, telling the Bolshevik officials to "take up a more honest trade".

At a regional congress in Oleksandrivsk, Nestor Makhno presented the Draft Declaration of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, which called for the establishment of "free soviets" outside of political party control.

Nestor Makhno denounced them as "counter-revolutionaries", causing them to walk out in protest.

When he returned to Katerynoslav in November 1919, the local railway workers looked to Nestor Makhno to pay their wages, which they had gone without for two months.

Nestor Makhno responded by proposing the workers self-manage the railways and levy payment for their services directly from the customers.

Nestor Makhno refused and the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee declared him to be an outlaw.

Once Nestor Makhno recovered, he immediately began to lead a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the Cheka and requisitioning units.

Nestor Makhno implemented a discriminatory policy for dealing with captured Red Army units: commanding officers and political commissars would be immediately shot, and the rank-and-file soldiers would be given the choice to either join the insurgent army or be stripped of their uniforms and sent home.

Nestor Makhno still hoped that victory over the Whites would oblige the Bolsheviks to honor his desire for soviet democracy and civil liberties in Ukraine.

Under the terms of the pact, Nestor Makhno was able to seek treatment from the medical corps of the Red Army, physicians and surgeons seeing to a wound in his ankle, where he had been hit by an expanding bullet.

Nestor Makhno was visited by the Hungarian communist leader Bela Kun, who gave him gifts, including over 100 photographs and postcards depicting the Executive Committee of the Communist International.

Nestor Makhno turned his attention towards reconstructing his vision of anarchist communism, overseeing the reestablishment of the local soviet and other anarchist projects.

Nestor Makhno had hoped that simply defeating a few Red divisions would halt the offensive but found himself having to change tactics in the face of his encirclement by overwhelming numbers.

Nestor Makhno led his detachment to the Galician border before suddenly swinging around and heading back across the Dnieper.

Nestor Makhno was unable to withdraw from the front and tend to his injuries, as his sotnia repeatedly came under attack by the Red Army.

Towards the end of May 1921, Nestor Makhno attempted to organize a large-scale offensive to take the Ukrainian Bolshevik capital of Kharkiv, pulling together thousands of partisans before he was forced to call it off due to substantial Red defenses.

Nestor Makhno continued to execute raids in the Don river basin despite having suffered several wounds.

Nestor Makhno came into contact with the exiled Ukrainian nationalists associated with Petliura, themselves allies of both Romania and Poland.

In prison, Nestor Makhno drafted his first memoir, which Peter Arshinov published in 1923 in his Berlin-based newspaper Anarkhicheskii vestnik.

Nestor Makhno sent open letters to exiled Don Cossacks and the Ukrainian Communist Party, and began to learn German and Esperanto.

Nestor Makhno was arrested and interrogated several times in the wake of Lenin's death.

Unable to secure a visa to travel to Germany and facing a severe strain on his marriage with Halyna, Nestor Makhno attempted suicide in April 1924 and was hospitalized by his injuries.

Nestor Makhno found work at a local foundry and a Renault factory but was forced to leave both jobs due to his health problems.

Nestor Makhno advised his family to move out to prevent them from contracting tuberculosis.

Between his debilitating illness, homesickness and a strong language barrier, Nestor Makhno fell into a deep depression.

Nestor Makhno collaborated with exiled Russian anarchists to establish the bimonthly libertarian communist journal Delo Truda, in which Makhno published an article in each issue over three years.

In June 1926, during a meal with May Picqueray and the exiled Russian-American Jewish anarchist Alexander Berkman in a Russian restaurant, Nestor Makhno met with the Ukrainian Jewish anarchist Sholem Schwarzbard, who went pale upon seeing the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura walk into the room.

Nestor Makhno attempted to dissuade him but the deed was carried out anyway.

Allegations of antisemitism were later disputed by historians and some of Nestor Makhno's biographers, including Paul Avrich, Peter Kenez, Michael Malet and Alexandre Skirda.

Nestor Makhno's wife grew to resent him, causing the couple to separate several times; Halyna unsuccessfully applied for permission to return to Soviet Ukraine.

Nestor Makhno came into a serious personal and political conflict with Volin, which would last until their deaths, resulting in the later volumes of Makhno's memoirs only being published posthumously.

In great pain, increasingly isolated and financially precarious, Nestor Makhno got odd jobs as an interior decorator and shoemaker.

Nestor Makhno was supported by the income of his wife, who worked as a cleaner.

Nestor Makhno spent most of this money on his daughter, neglecting his own self-care, which contributed further to his declining health.

Nestor Makhno was particularly impressed by the revolutionary traditions of the Spanish working classes and the tight organization of the Spanish anarchists, declaring that if a revolution broke out in Spain before he died, then he would join the fight.

Nestor Makhno spent his last years writing criticisms of the Bolsheviks and encouraging other anarchists to learn from the mistakes of the Ukrainian experience.

Nestor Makhno was cremated three days after his death; five hundred people attended his funeral at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Nestor Makhno is a local hero in his hometown of Huliaipole, where a statue of him stands in its main town square.

Nestor Makhno was the antagonist in the 1923 Red Devils, portrayed by the Odesa gangster and part-time actor Vladimir Kucherenko.

Nestor Makhno reprised his role in the 1926 sequel Savur-Mohyla and returned to crime under the pseudonym "Makhno".

In London, a group of squatters inspired by Nestor Makhno occupied the mansion of Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, in protest against the invasion.