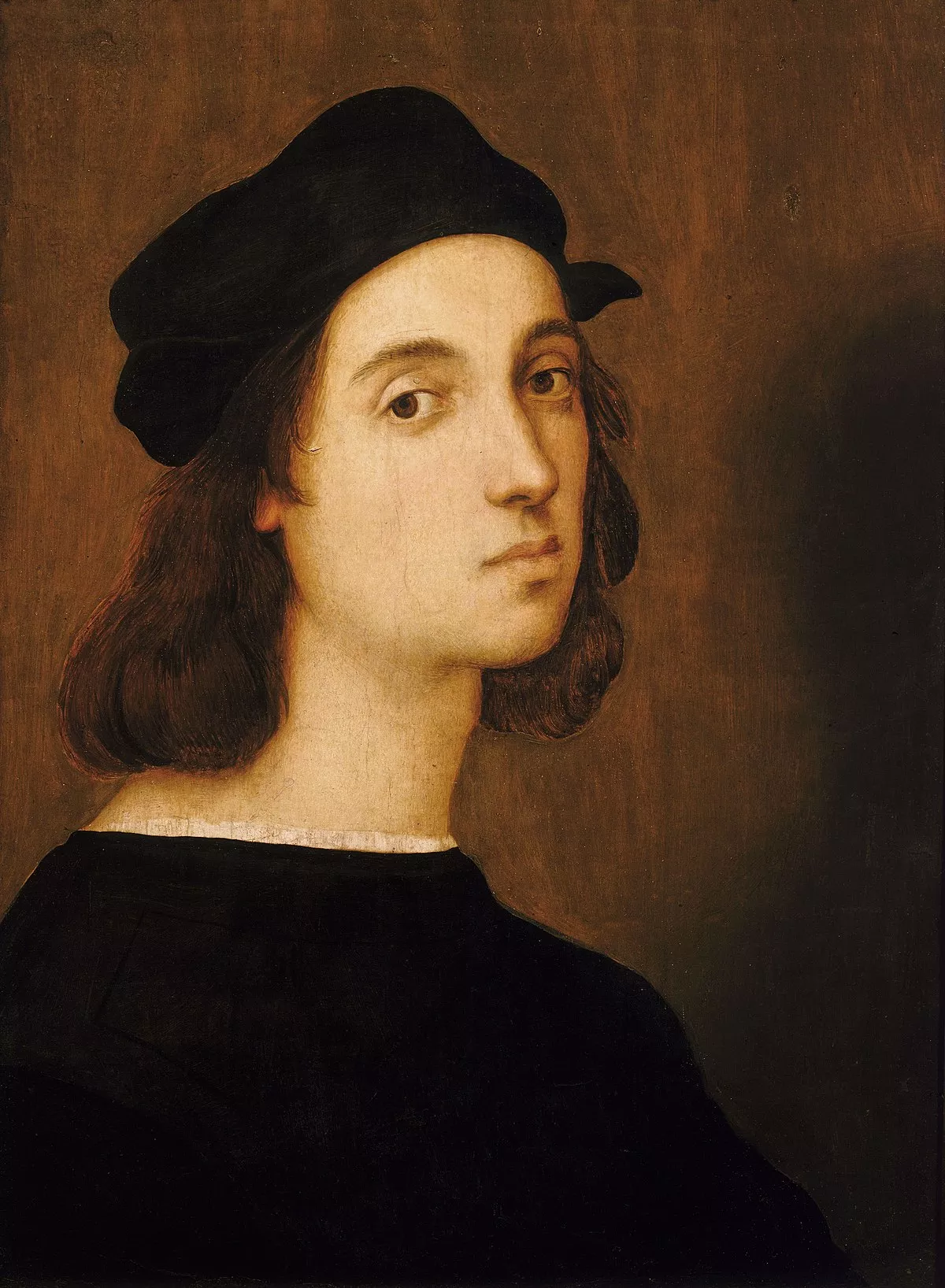

1.

1. Raphael's work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur.

1.

1. Raphael's work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur.

Raphael probably trained in the workshop of Pietro Perugino, and was described as a fully trained "master" by 1500.

Raphael worked in or for several cities in north Italy until in 1508 he moved to Rome at the invitation of Pope Julius II, to work on the Apostolic Palace at the Vatican.

Raphael was given a series of important commissions there and elsewhere in the city, and began to work as an architect.

Raphael was still at the height of his powers at his death in 1520.

Raphael was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop and, despite his early death at 37, leaving a large body of work.

Raphael's career falls naturally into three phases and three styles, first described by Giorgio Vasari: his early years in Umbria, then a period of about four years absorbing the artistic traditions of Florence, followed by his last hectic and triumphant twelve years in Rome, working for two popes and their close associates.

Many of his works are found in the Vatican Palace, where the frescoed Raphael Rooms were the central, and the largest, work of his career.

Raphael was extremely influential in his lifetime, though outside Rome his work was mostly known from his collaborative printmaking.

Castiglione moved to Urbino in 1504, when Raphael was no longer based there but frequently visited, and they became good friends.

Raphael became close to other regular visitors to the court: Pietro Bibbiena and Pietro Bembo, both later cardinals, were already becoming well known as writers, and would later be in Rome during Raphael's period there.

Raphael did not receive a full humanistic education however; it is unclear how easily he read Latin.

Raphael was thus orphaned at eleven; his formal guardian became his only paternal uncle, Bartolomeo, a priest, who subsequently engaged in litigation with his stepmother.

Raphael had already shown talent, according to Vasari, who says that Raphael had been "a great help to his father".

Raphael's first documented work was the Baronci Altarpiece for the church of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino in Citta di Castello, a town halfway between Perugia and Urbino.

Raphael painted many small and exquisite cabinet paintings in these years, probably mostly for the connoisseurs in the Urbino court, like the Three Graces and St Michael, and he began to paint Madonnas and portraits.

In 1502 he went to Siena at the invitation of another pupil of Perugino, Pinturicchio, "being a friend of Raphael and knowing him to be a draughtsman of the highest quality" to help with the cartoons, and very likely the designs, for a fresco series in the Piccolomini Library in Siena Cathedral.

Raphael was evidently already much in demand even at this early stage in his career.

Raphael led a "nomadic" life, working in various centres in Northern Italy, but spent a good deal of time in Florence, perhaps from about 1504.

Raphael's figures begin to take more dynamic and complex positions, and though as yet his painted subjects are still mostly tranquil, he made drawn studies of fighting nude men, one of the obsessions of the period in Florence.

Raphael would have been aware of his works in Florence, but in his most original work of these years, he strikes out in a different direction.

In 1508, Raphael moved to Rome, where he resided for the rest of his life.

Unlike Michelangelo, who had been kept lingering in Rome for several months after his first summons, Raphael was immediately commissioned by Julius to fresco what was intended to become the Pope's private library at the Vatican Palace.

Raphael was then given further rooms to paint, displacing other artists including Perugino and Signorelli.

Raphael completed a sequence of three rooms, each with paintings on each wall and often the ceilings too, increasingly leaving the work of painting from his detailed drawings to the large and skilled workshop team he had acquired, who added a fourth room, probably only including some elements designed by Raphael, after his early death in 1520.

Raphael completed the first section of his work in 1511 and the reaction of other artists to the daunting force of Michelangelo was the dominating question in Italian art for the following few decades.

Raphael, who had already shown his gift for absorbing influences into his own personal style, rose to the challenge perhaps better than any other artist.

Raphael designed several other buildings, and for a short time was the most important architect in Rome, working for a small circle around the Papacy.

Raphael produced a design from which the final construction plans were completed by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger.

Raphael wrote a letter to Pope Leo suggesting ways of halting the destruction of ancient monuments, and proposed a visual survey of the city to record all antiquities in an organised fashion.

Raphael intended to make an archaeological map of ancient Rome but this was never executed.

Raphael designed some of the decoration for the Villa Madama, the work in both villas being executed by his workshop.

Raphael designed and painted the Loggie at the Vatican, a long thin gallery then open to a courtyard on one side, decorated with Roman-style grottesche.

Raphael produced a number of significant altarpieces, including The Ecstasy of St Cecilia and the Sistine Madonna.

Raphael painted several of his works on wood support but he used canvas and he was known to employ drying oils such as linseed or walnut oils.

Raphael's palette was rich and he used almost all of the then available pigments such as ultramarine, lead-tin-yellow, carmine, vermilion, madder lake, verdigris and ochres.

Vasari says that Raphael eventually had a workshop of fifty pupils and assistants, many of whom later became significant artists in their own right.

However though both Penni and Giulio were sufficiently skilled that distinguishing between their hands and that of Raphael himself is still sometimes difficult, there is no doubt that many of Raphael's later wall-paintings, and probably some of his easel paintings, are more notable for their design than their execution.

The printmakers and architects in Raphael's circle are discussed below.

Raphael was one of the finest draftsmen in the history of Western art, and used drawings extensively to plan his compositions.

Raphael made unusually extensive use, on both paper and plaster, of a "blind stylus", scratching lines which leave only an indentation, but no mark.

Raphael was one of the last artists to use metalpoint extensively, although he made superb use of the freer medium of red or black chalk.

Raphael made no prints himself, but entered into a collaboration with Marcantonio Raimondi to produce engravings to Raphael's designs, which created many of the most famous Italian prints of the century, and was important in the rise of the reproductive print.

Raphael's interest was unusual in such a major artist; from his contemporaries it was only shared by Titian, who had worked much less successfully with Raimondi.

Raphael made preparatory drawings, many of which survive, for Raimondi to translate into engraving.

Outside Italy, reproductive prints by Raimondi and others were the main way that Raphael's art was experienced until the twentieth century.

Baviero Carocci, called "Il Baviera" by Vasari, an assistant who Raphael evidently trusted with his money, ended up in control of most of the copper plates after Raphael's death, and had a successful career in the new occupation of a publisher of prints.

From 1517 until his death, Raphael lived in the Palazzo Caprini, lying at the corner between piazza Scossacavalli and via Alessandrina in the Borgo, in rather grand style in a palace designed by Bramante.

Raphael never married, but in 1514 became engaged to Maria Bibbiena, Cardinal Bibbiena's niece; he seems to have been talked into this by his friend the cardinal, and his lack of enthusiasm seems to be shown by the marriage not having taken place before she died in 1520.

Raphael is said to have had many affairs, but a permanent fixture in his life in Rome was "La Fornarina", Margherita Luti, the daughter of a baker named Francesco Luti from Siena who lived at Via del Governo Vecchio.

Raphael was made a "Groom of the Chamber" of the Pope, which gave him status at court and an additional income, and a knight of the Papal Order of the Golden Spur.

Raphael dictated his will, in which he left sufficient funds for his mistress's care, entrusted to his loyal servant Baviera, and left most of his studio contents to Giulio Romano and Penni.

Raphael was highly admired by his contemporaries, although his influence on artistic style in his own century was less than that of Michelangelo.

Raphael was seen as the ideal model by those disliking the excesses of Mannerism:.

Raphael's compositions were always admired and studied, and became the cornerstone of the training of the Academies of art.

Raphael was seen as the best model for the history painting, regarded as the highest in the hierarchy of genres.

Raphael did not possess so many excellences as Raffaelle, but those he had were of the highest kind.

In Germany, Raphael had an immense influence on religious art of the Nazarene movement and Dusseldorf school of painting in the 19th century.