1.

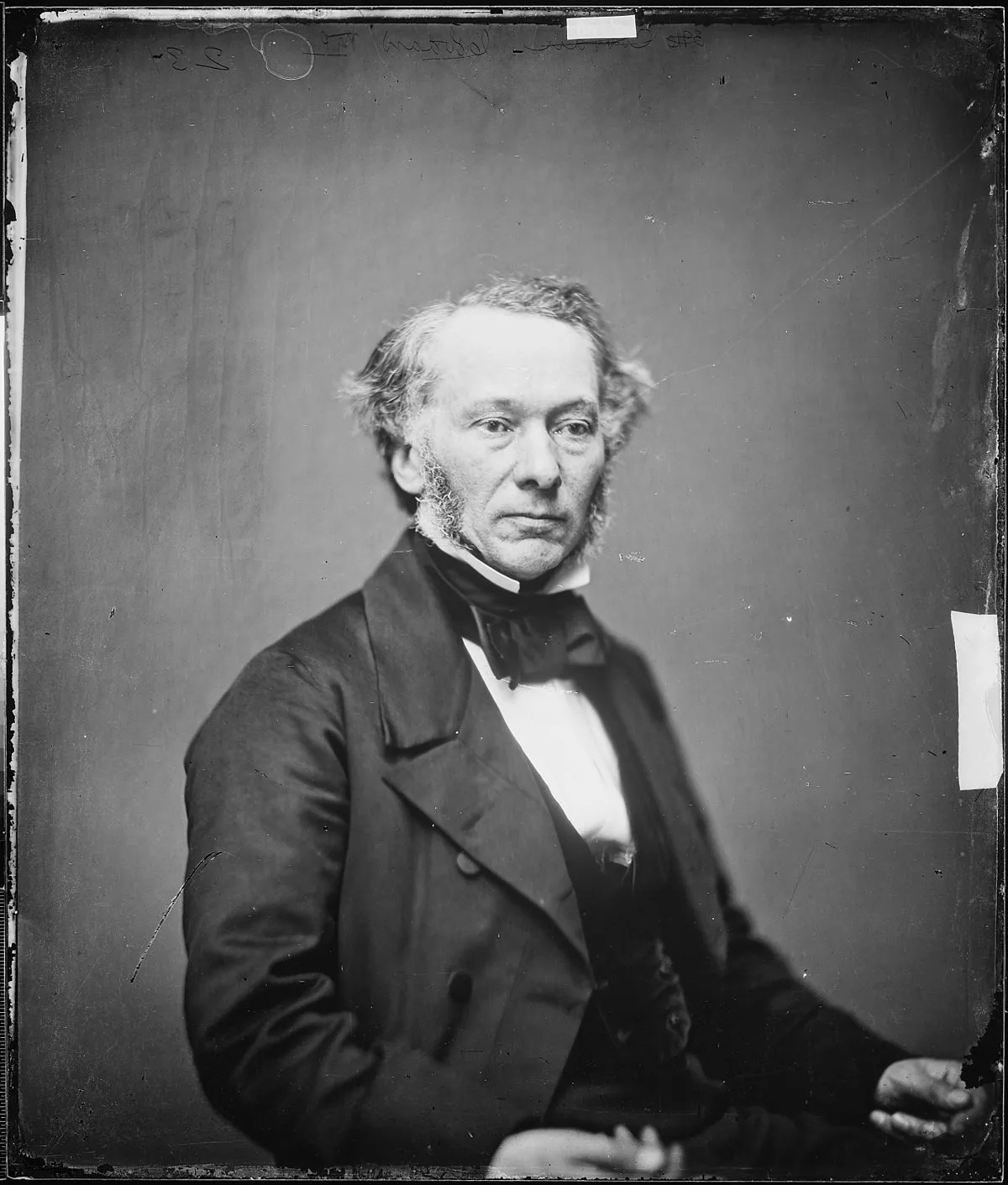

1. Richard Cobden was an English Radical and Liberal politician, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace.

1.

1. Richard Cobden was an English Radical and Liberal politician, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace.

Richard Cobden was born at a farmhouse called Dunford, in Heyshott near Midhurst, in Sussex.

Richard Cobden was the fourth of 11 children born to Millicent and William Cobden.

Richard Cobden's family had been resident in that neighbourhood for many generations, occupied in trade and agriculture.

Richard Cobden's grandfather, Richard Cobden, owned Bex Mill in Heyshott and was a prosperous maltster who served as bailiff and chief magistrate at Midhurst.

Richard Cobden attended a dame school and then Bowes Hall School in the North Riding of Yorkshire.

Richard Cobden's relative, noting the lad's passionate addiction to study, solemnly warned him against indulging such a taste, as likely to prove a fatal obstacle to his success in commercial life.

Richard Cobden was undeterred and made good use of the library of the London Institution.

In 1828, Richard Cobden set up his own business with Sheriff and Gillet, partly with capital from John Lewis, acting as London agents for Fort Brothers, Manchester calico printers.

The Manchester outlet came under the direct management of Richard Cobden, who settled there in 1832, beginning a long association with the city.

Richard Cobden lived in a house on Quay Street, which is called Cobden House.

Richard Cobden advocated the principles of peace, non-intervention, retrenchment and free trade to which he continued faithfully to abide.

Richard Cobden paid a visit to the United States, landing in New York on 7 June 1835.

Richard Cobden devoted about three months to this tour, passing rapidly through the seaboard states and the adjacent portion of Canada, and collecting as he went large stores of information respecting the condition, resources and prospects of the nation.

Richard Cobden soon became a conspicuous figure in Manchester political and intellectual life.

Richard Cobden championed the foundation of the Manchester Athenaeum and delivered its inaugural address.

Richard Cobden was a member of the chamber of commerce and was part of the campaign for the incorporation of the city, being elected one of its first aldermen.

Richard Cobden began to take a warm interest in the cause of popular education.

Richard Cobden was not afraid to take his challenge in person to the agricultural landlords or to confront the working class Chartists, led by Feargus O'Connor.

In 1841, Sir Robert Peel having defeated the Melbourne ministry in parliament, there was a general election, and Richard Cobden was returned as the new member for Stockport.

Richard Cobden's opponents had confidently predicted that he would fail utterly in the House of Commons.

Richard Cobden did not wait long after his admission into that assembly in bringing their predictions to the test.

On 21 April 1842, with 67 other MPs, Richard Cobden voted for the motion of William Sharman Crawford to form a committee to consider the demands of the People's Charter : votes for working men, protected by secret ballot.

On 17 February 1843, Richard Cobden launched an attack on Peel, holding him responsible for the miserable and disaffected state of the nation's workers.

Peel's Tory party, catching at this hint, threw themselves into a frantic state of excitement, and when Richard Cobden attempted to explain that he meant official, not personal responsibility, he was drowned out.

Richard Cobden had sacrificed his business, his domestic comforts and for a time his health to the campaign.

Lord John Russell, who, soon after the repeal of the Corn Laws, succeeded Peel as prime minister, invited Richard Cobden to join his government but Richard Cobden declined the invitation.

Richard Cobden had hoped to find some restorative privacy abroad but his fame had spread throughout Europe and he found himself lionised by the radical movement.

Richard Cobden visited in succession France, Spain, Italy, Germany and Russia, and was honoured everywhere he went.

In June 1848 Richard Cobden moved his family from Manchester to Paddington, London, taking a house at 103 Westbourne Terrace.

When Richard Cobden returned from abroad, he addressed himself to what seemed to him the logical complement of free trade, namely, the promotion of peace and the reduction of naval and military armaments.

Richard Cobden was a supporter of non-interventionism and his abhorrence of war amounted to a passion and, in fact, his campaigns against the Corn Laws were motivated by his belief that free trade was a powerful force for peace and defence against war.

Richard Cobden knowingly exposed himself to the risk of ridicule and the reproach of utopianism.

Richard Cobden was not successful in either case, nor did he expect to be.

Richard Cobden published How Wars are got up in India: The Origins of the Burmese War in 1853.

Again confronting public sentiment, Richard Cobden, who had travelled in Turkey, and had studied its politics, was dismissive of the outcry about maintaining the independence and integrity of the Ottoman Empire.

Richard Cobden denied that it was possible to maintain them, and no less strenuously denied that it was desirable.

Richard Cobden believed that the jealousy of Russian aggrandisement and the dread of Russian power were absurd exaggerations.

Richard Cobden maintained that the future of European Turkey was in the hands of the Christian population, and that it would have been wiser for Britain to ally herself with them rather than with what he saw as the doomed and decaying Islamic power.

Richard Cobden brought forward a motion in parliament to this effect, which led to a long and memorable debate, lasting over four nights, in which he was supported by Sidney Herbert, Sir James Graham, William Gladstone, Lord John Russell and Benjamin Disraeli, and which ended in the defeat of Lord Palmerston by a majority of sixteen.

Richard Cobden was thus relegated to private life, and retiring to his country house at Dunford, he spent his time in perfect contentment in cultivating his land and feeding his pigs.

Richard Cobden took advantage of this season of leisure to pay another visit to the United States.

Richard Cobden then addressed himself to the French ministers, and had much earnest conversation, especially with Eugene Rouher, whom he found well inclined to the economical and commercial principles which he advocated.

Richard Cobden had to contend with the bitter hostility of the French protectionists, which occasioned a good deal of vacillation on the part of the emperor and his ministers.

Richard Cobden was, moreover, assailed with great violence by a powerful section of the British press, while the large number of minute details with which he had to deal in connection with proposed changes in the French tariff, involved a tax on his patience and industry which would have daunted a less resolute man.

Richard Cobden was therefore deeply disappointed and distressed to find the old feeling of distrust still actively fomented by the press and some of the leading politicians of the country.

Richard Cobden was characterised from his early years by energy and sociability, but particularly by a desire to learn and understand the traits of the world, a characteristic that stayed with him throughout his life.

Richard Cobden had many friends from many walks of life.

For several years Richard Cobden was unwell with bronchial irritation and difficulty of breathing.

Richard Cobden remained intellectually engaged in seeking international peace and other themes.

Richard Cobden's grave was surrounded by a large crowd of mourners, among whom were Gladstone, Bright, Milner Gibson, Charles Villiers and a host besides from all parts of the country.

Richard Cobden is above all", he added, "in our eyes the representative of those sentiments and those cosmopolitan principles before which national frontiers and rivalries disappear; whilst essentially of his country, he was still more of his time; he knew what mutual relations could accomplish in our day for the prosperity of peoples.

Richard Cobden has been called "the greatest classical-liberal thinker on international affairs" by the libertarian and historian Ralph Raico.

In 1840, Richard Cobden married Catherine Anne Williams, a Welsh woman.

Richard Cobden was committed to his family, although his public life was absorbing.

Richard Cobden considered that it was "natural" for Britain to manufacture for the world and exchange for agricultural products of other countries.

Richard Cobden advocated the repeal of the Corn Laws, which not only made food cheaper, but helped develop industry and benefit labour.

Richard Cobden correctly saw that other countries would be unable to compete with Britain in manufacture in the foreseeable future.

Richard Cobden perceived that the rest of the world should follow Britain's example: "if you abolish the corn-laws honestly, and adopt free trade in its simplicity, there will not be a tariff in Europe that will not be changed in less than five years".

In 1866, the Richard Cobden Club was founded to promote "Peace, Free Trade and Goodwill Among Nations".

Richard Cobden "symbolized the liberal vision of a peaceful, prosperous global order held together by the benign forces of Free Trade" like no other nineteenth century figure.

Those who expressed astonishment that the intelligent workman did not look askance at the manufacturer, Richard Cobden, had overlooked the fact that he gave the people cheap food and abundant employment, and did far more; that he exploded the economic basis of class government and class subjection.

To-day the ideas of Richard Cobden were in revolt against selfish nationalism.

Hirst said in 1941, during the Second World War, that Richard Cobden's ideas "stand out in almost complete opposition to the 'gospel' according to Marx":.

Richard Cobden had no sense of patriotism or love of country.

Richard Cobden demanded the confiscation of private property and a new dictatorship, the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Just as Richard Cobden interpreted and practised the precepts of Adam Smith, so Lenin interpreted and practised the precepts of Karl Marx.

Richard Cobden was named by Ferdinand de Lesseps as a founder of the Suez Canal Company.