1.

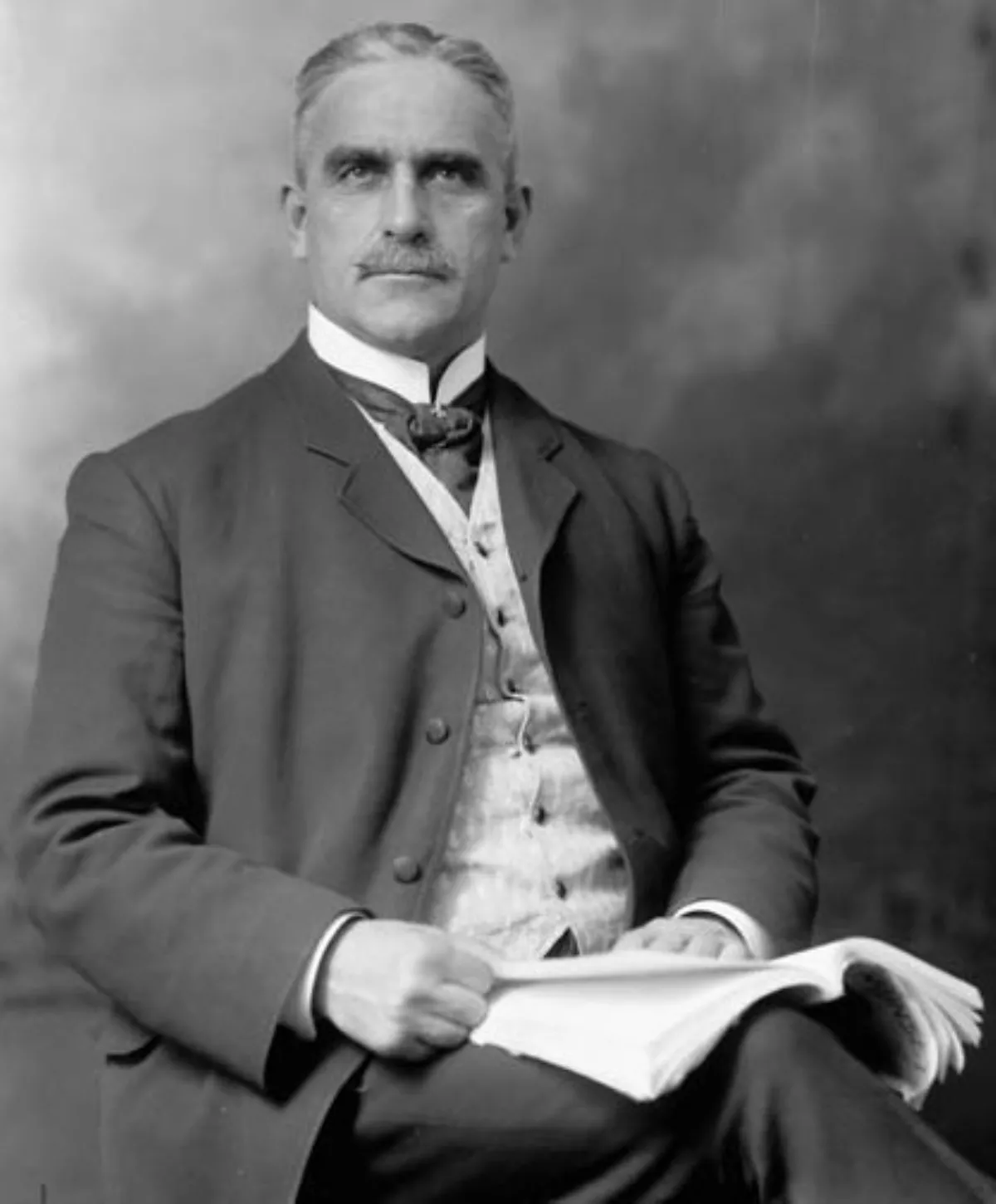

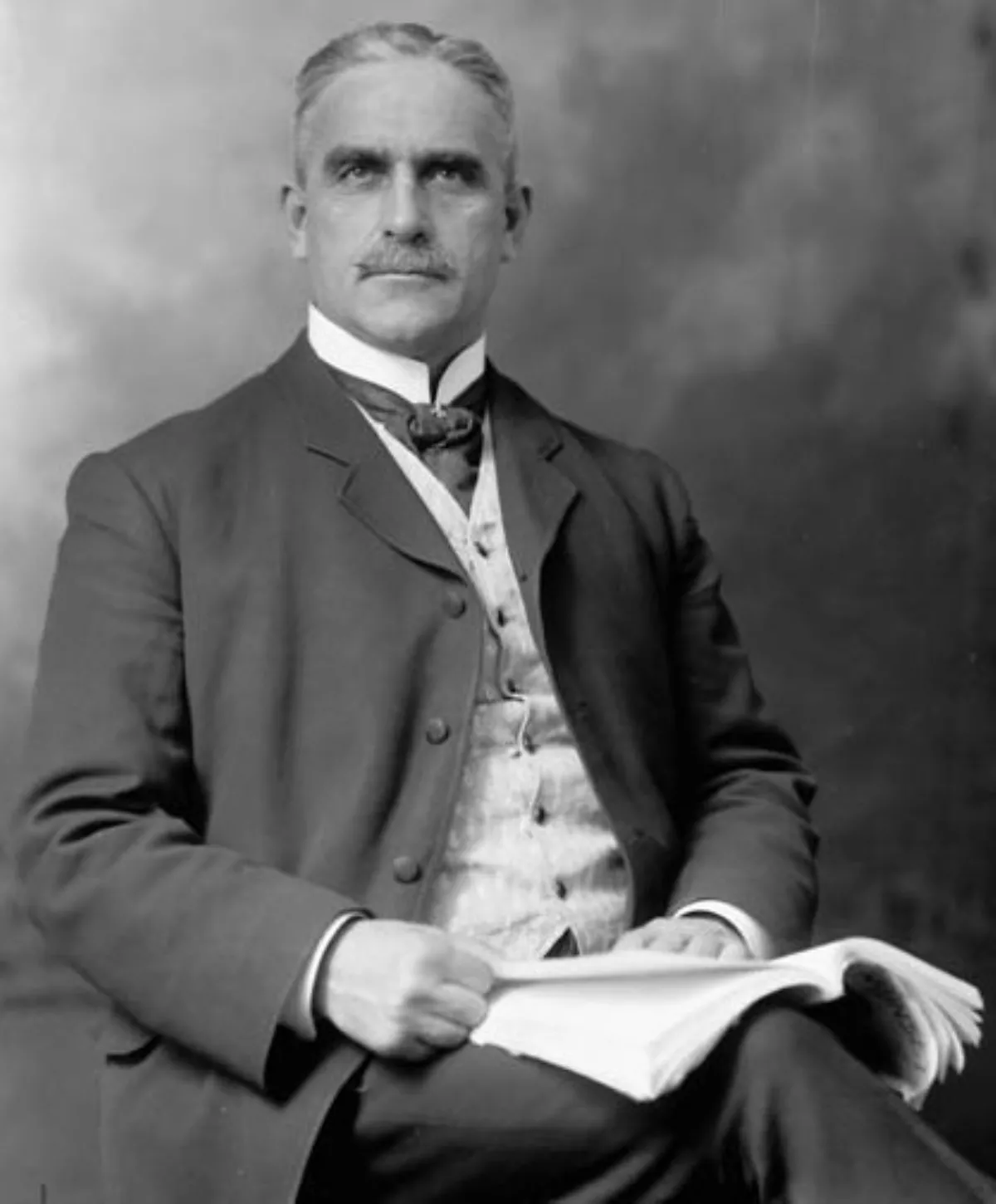

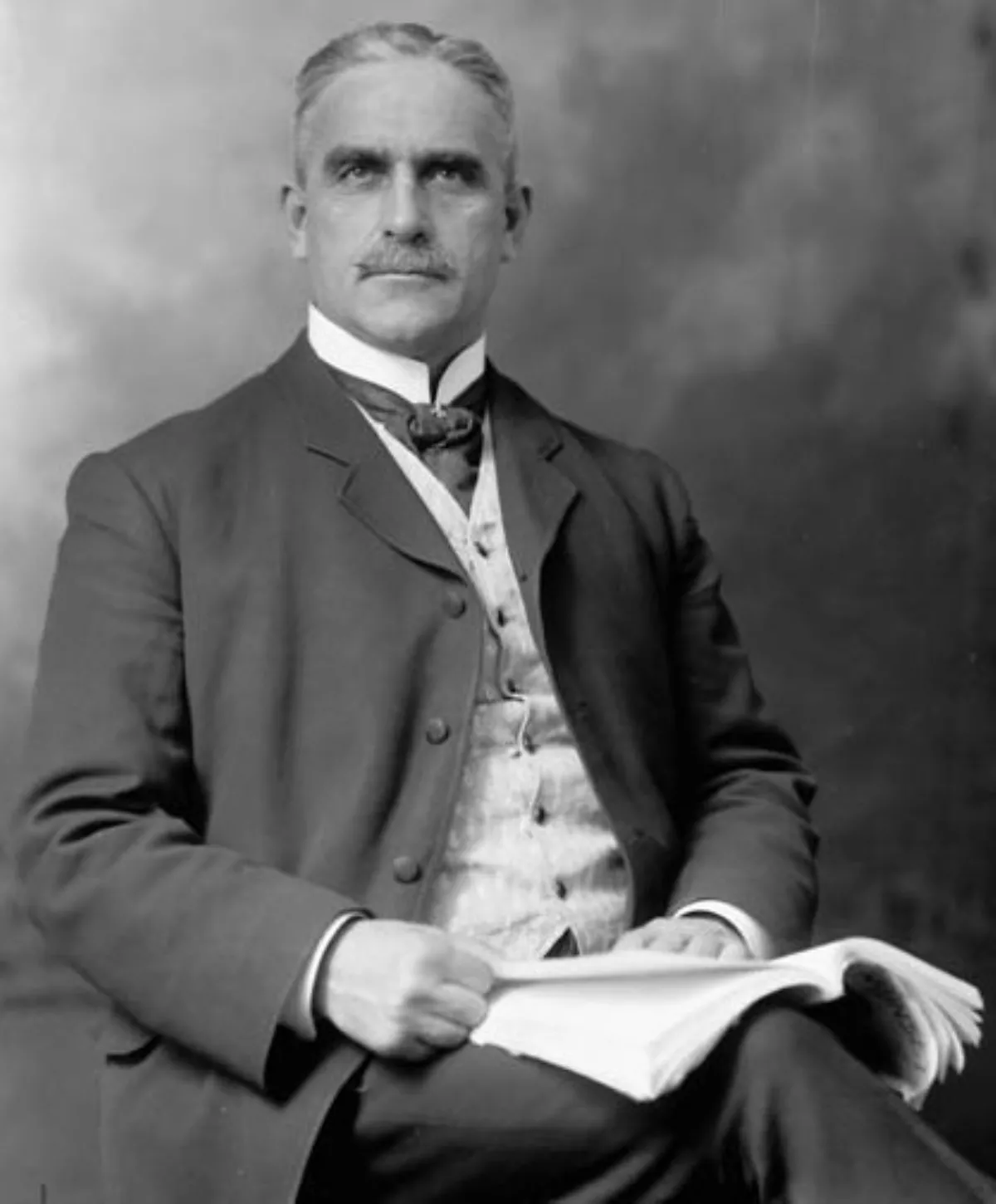

1. Sam Hughes was a son of John Hughes from County Tyrone, Ireland, and Caroline Hughes, a Canadian descended from Huguenots and Ulster Scots.

1.

1. Sam Hughes was a son of John Hughes from County Tyrone, Ireland, and Caroline Hughes, a Canadian descended from Huguenots and Ulster Scots.

Sam Hughes was educated in Durham County, Ontario and later attended the Toronto Normal School and the University of Toronto.

Sam Hughes liked to see himself as embodying the Victorian values of hard work, self discipline, strength and manliness.

Tall, muscular, and broad-shouldered, Sam Hughes excelled at sports, being especially talented at lacrosse.

Sam Hughes later claimed, in the British Who's Who, to have "personally offered to raise" Canadian contingents for service in "the Egyptian and Sudanese campaigns, the Afghan Frontier War, and the Transvaal War".

Sam Hughes was a teacher from 1875 to 1885 at the Toronto Collegiate Institute, where he was noted for his eccentricities such as his habit of chewing on his chalk when delivering his lectures.

Sam Hughes abandoned teaching as he had trouble supporting a wife and three children on his salary while teaching offered little prospect of promotion.

Sam Hughes was the paper's publisher from 1885 to 1897.

Shortly after he began his proprietorship of the Victoria Warder in July 1885, Sam Hughes joined the local Liberal-Conservative Association.

Macdonald noted in 1888 that "Sam Hughes is one of our best friends", as the Victoria Warder very strongly supported the Conservatives, making him a useful man for the Tories in the rural Victoria County, where most people got their news from his newspaper.

At the time when Sam Hughes arrived in Victoria County, it was a mostly forested area where lumbering was the chief industry, though agriculture was increasing as the trees were cut down.

Sam Hughes's grandson wrote that for Hughes Victoria County was his "spiritual home".

Victoria County in the 19th century was considered to be a "rough" frontier area, and during his tempestuous time as editor, Sam Hughes was sued for libel, there was an arson attempt against the Victoria Warder and was at least one assassination attempt against him when he was shot at while leaving his newspaper office.

In 1885, Sam Hughes tried to volunteer for the expeditionary force sent to put down the North-West Rebellion led by the Metis Louis Riel, but he was refused despite being a very active member of the militia.

About the Canadian victory in the Battle of Batoche, Sam Hughes wrote in an editorial that "regular troops were all right for police purposes in times of peace and for training schools, but beyond that they are an injury to the nation".

Sam Hughes equated masculinity with toughness, and argued that militia service would toughen up Canadian men who might otherwise go soft living in an urban environment full of labor-saving devices.

Victoria County had as a percentage of the population the largest number of Orangemen in Canada in the late 19th century, and Sam Hughes who sat on the executive board of the local Lodge of the Loyal Orange Order in the county was able to use the Orangemen to provide a reliable group of voters when seeking election to the House of Commons throughout his career.

The combative Sam Hughes enjoyed brawling with Irish Catholic immigrants on trips to Toronto.

Two justices at the Queen's Bench in Toronto ruled that the evidence of electoral fraud presented by Sam Hughes was overwhelming, and ordered a by-election, held on 11 February 1892.

In January 1894, Sam Hughes was involved in a brawl on Lindsay's main street with a Roman Catholic blacksmith named Richard Kylie, which led him to being convicted of assault and fined $500.

The Manitoba Schools Question proved to be one of the most bitterly divisive issues of the 1890s, and Sam Hughes emerged as a spokesman for those who urged the Dominion government not to intervene, arguing that if Manitoba did not wish to provide education in French, that was its right.

Sam Hughes justified his views under the grounds of secularism, writing in 1892 "all churches are a simple damned nuisance".

Sam Hughes used his influence with the Orange Order to try to keep them from inflaming the Manitoba Schools Question, and to convince them to accept Thompson as the next Conservative leader to replace the ailing Sir John Abbott.

Sam Hughes tried to persuade the Orangemen to accept a Catholic prime minister.

When Thompson died in December 1894, Sam Hughes supported the candidacy of Sir Charles Tupper against Senator Mackenzie Bowell, but Bowell prevailed and became the next prime minister.

Sam Hughes supported Tupper's "friendly means" compromise of secular education in Manitoba with religious instruction after the school day had officially ended.

At a national meeting of the Orange Order in Collingwood in May 1896, Sam Hughes spoke in favour of Tupper and was almost expelled from the Order.

Sam Hughes held on to his seat by arguing that the affairs of Manitoba were irrelevant to Victoria County and he understood local issues far better than his opponent.

The election of 1896 resulted in a Liberal victory, and in the new, much smaller Conservative caucus, Sam Hughes stood out as the few MPs whose reputation had been enhanced by the Manitoba Schools Question.

Unlike other Conservative MPs like George Foster who argued that the Manitoba Act had guaranteed the right to a Catholic education in French, and it was the duty of the Dominion government to uphold the law, Sam Hughes had no interest in minority rights.

Sam Hughes felt that a secular education system was superior to a religious one, and that the language of instruction in Manitoba schools should be English.

Sam Hughes developed a strong contempt for the British military while in South Africa and came away with the idea that frontier living had made the Canadians tougher and hardier soldiers than the British.

The Canadian historian Pierre Berton wrote that Sam Hughes "hated the British Army".

Sam Hughes used the performance of irregular cavalry units from Canada and Australia to support his theory, noting that the "cowboy" units recruited from the Australian Outback and the Canadian Prairies were the ones most effective at hunting down the kommandos.

Haycock noted that Sam Hughes seemed to have no interest in understanding why the commandos had been defeated, instead presenting the war as almost a Boer victory.

The more that the British Army rejected the Ross rifle as unsuitable, the more it persuaded Sam Hughes of its superiority, though Morton noted that the British objections to the Ross rifle were sound as it was a hunting rifle that overheated after rapid firing and was too easily jammed by dirt.

Balfour wrote that Sam Hughes was chivalrous towards Boer civilians, apologising to the wife of a man he arrested as a guerrilla for taking away her husband while Curtis stated that Sam Hughes always paid for the food he had taken from farms out on the veld, saying he was no thief.

Letters in which Sam Hughes charged the British military with incompetence had been published in Canada and South Africa.

Sam Hughes had flagrantly disobeyed orders in a key operation by granting favourable terms to an enemy force which surrendered to him.

Sam Hughes was well known for his attacks upon the immigration policy of the Laurier government, charging that Canada needed more immigrants of "good British stock".

Sam Hughes was active in the Imperial Federation movement, regularly corresponding with both Joseph Chamberlain and Alfred Milner on the issue, and every year from 1905 onward, introduced a resolution in the House of Commons calling for an "equal partnership union" of the Dominions with the United Kingdom.

Sam Hughes repeatedly objected to Chamberlain's concept of the British prime minister and cabinet deciding questions for the Dominions, and Haycock wrote what Sam Hughes wanted sounds very similar to the British Commonwealth that emerged after 1931.

In 1906, after repeatedly hammering the immigration minister, Clifford Sifton in debate, Sam Hughes's motion calling for the Canadian government to give preference in handing out land in the Prairie provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba to veterans of the British Army was accepted as policy.

In 1907 Sam Hughes told the House of Commons that Catholic immigrants from Europe were "a curse upon Canada".

Sam Hughes, who claimed to have been offered but declined the post of Deputy Minister of Militia in 1891, was appointed Minister of Militia after the election of Borden in 1911, with the aim of creating a distinct Canadian army within the British Empire, to be used in case of war.

Sam Hughes wrote a letter to the Governor General, the Duke of Connaught, about his longtime demand for the Victoria Cross.

Hughes's views later did much to put off French-Canadians and Irish-Canadians from supporting the war effort in World War I Chartrand further wrote that Hughes was a megalomaniac with a grotesquely inflated sense of his own importance who "would admit no contradiction to his views".

Sam Hughes was by then a colonel in the militia, and he insisted on wearing his uniform at all times, including cabinet meetings.

In 1912, Sam Hughes promoted himself to the rank of major-general.

An energetic minister, Sam Hughes travelled all over Canada in his private luxury railroad car to attend parades and manoeuvres by the militia.

Sam Hughes saw the Dominions as equal partners of the United Kingdom in the management of the British empire, making claims for powers for Ottawa that anticipated the 1931 Statute of Westminster, and fiercely fought against attempts on the part of London to treat Canada in a mere colonial role.

In December 1911, Sam Hughes announced that he was going to increase the militia budget and built more camps and drill halls for the militia.

Sam Hughes was openly hostile to the Permanent Active Militia, or Permanent Force, as Canada's small professional army was known, and praised the Non-Permanent Active Militia as reflecting the authentic fighting spirit of Canada.

Critics charged that Sam Hughes favoured the Militia as it allowed him opportunities for patronage as he gave various friends and allies officers' commissions in the militia that did not exist with the Permanent Force, where promotion was based on merit.

Sam Hughes did not have much interest in the Royal Canadian Navy, which had been founded by Laurier in 1910, in large part because the Navy by its very existence required a full-time force of professionals, which did not fit in well with the Defence Minister's enthusiasm for citizen-soldiers.

Sam Hughes justified the move as upholding secularism, but Quebec newspapers noted that Sam Hughes was an Orangeman, and blamed his decision as due to the anti-Catholic prejudices one could expect from a member of the Loyal Orange Order.

Sam Hughes used the Defence Department funds to give a free Ford Model T car to every militia colonel in Canada, a move which caused much criticism.

In 1913, Sam Hughes went on an all-expenses paid junket to Europe together with his family, his secretaries, and various militia colonels who were his friends and their families.

Sam Hughes justified the trip, which lasted several months, as necessary to observe military manoeuvres in Britain, France and Switzerland, but to many Canadians, it appeared more like an expensive vacation taken with the taxpayer's money.

Sam Hughes's intention was to make militia service compulsory for every able-bodied male, a plan that caused considerable public opposition.

The reasons Sam Hughes gave for a larger Swiss-style militia were moral, not military.

Much to everyone's surprise, Sam Hughes disregarded the General Staff's plan and refused to mobilize the militia, instead creating a brand new organization called the Canadian Expeditionary Force made up of numbered battalions that was separate from the militia.

Likewise, when John Farthing, the Anglican bishop of Montreal, visited Sam Hughes to complain about the shortage of Church of England chaplains at Valcartier to tend to the spiritual needs of Anglican volunteers, Sam Hughes burst into a rage and began to loudly swear at Farthing, making liberal use of a number of four letter words not normally used to address an Anglican bishop, who was predictably shocked.

The Duke of Connaught wrote in a report to London that Sam Hughes was "off his base".

Sam Hughes encouraged the recruitment of volunteers following the First World War's outbreak and ordered the construction of Camp Valcartier on August 7,1914, demanding it to be finished by the time the entire force was assembled.

However, Sam Hughes was praised for the speed of his actions by Prime Minister Borden and members of the cabinet.

All of the officers Sam Hughes chose to command the brigades and battalions of the First Contingent were Anglo-Canadians.

Sam Hughes was determined that the CEF fight together and upon arriving in London, went dressed in his full ceremonial uniform as a major-general in the Canadian militia, to see Kitchener.

Sam Hughes clashed with Kitchener and insisted quite vehemently that the CEF not be broken up.

Sam Hughes constantly sought to undermine Alderson's command, regularly involving himself in divisional matters that were not the normal concern of a defence minister.

Sam Hughes was ecstatic at the news that the Canadians had won their first battle, which in his own mind validated everything he had done as defence minister.

Sam Hughes himself had wanted to take command of the Canadian Corps, but Borden had prevented this.

In May 1915, Sam Hughes first learned that Currie had embezzled some $10,000 from his militia regiment in Victoria in June 1914 and the police were recommending criminal charges be brought against him.

Sam Hughes was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, on August 24,1915.

In spite of mounting criticism from 1915 onward at the way in which Sam Hughes ran the Defence Department in wartime, the politically indebted Borden kept Sam Hughes on.

Sam Hughes's methods were unorthodox and chaotic, but Sam Hughes argued he was merely cutting through the red-tape to help "the boys" in the field.

Sam Hughes was enraged at the way that Flavelle had taken over an important function from his department, and even more that the Imperial Munitions Board was far more efficient and honest than the Defence Department had been.

The 4th Division was commanded by David Watson, the owner of the Quebec Chronicle newspaper, who been personally chosen by Sam Hughes, who thought highly of him.

Sam Hughes reluctantly accepted Japanese-Canadians and Chinese-Canadians for the CEF and assigned black Canadians to construction units.

In marked contrast to his attitudes towards black Canadian and Asian Canadian volunteers, Sam Hughes encouraged the enlistment of First Nations volunteers into the CEF as it was believed that Indians would make for ferocious soldiers.

Borden was unaware until early 1916 that Sam Hughes had recruited a battalion of American volunteers, which he first learned of after receiving American complaints about Canadian violations of American neutrality.

Bullock, whom Sam Hughes had appointed his chief recruiter for the American Legion, had received from Sam Hughes a colonel's commission in the CEF despite having no military experience.

Between 1914 and 1916, Sam Hughes raised in total about half million volunteers for the CEF, of whom only about 13,000 were French-Canadians.

Sam Hughes was widely resented and disliked by the men of the CEF and when Sam Hughes visited Camp Borden in July 1916, "his boys" loudly booed him, blaming the minister for the shortages of water at Camp Borden.

The most important of the officers in England was Major-General John Wallace Carson, a mining magnate from Montreal and a friend of Sam Hughes, who proved himself a skillful intriguer.

In September 1916, Sam Hughes acting on his own and without informing Borden, announced in London the formation of the "Acting Overseas Sub-Militia Council" to be chaired by Carson with Sam Hughes's son-in-law to serve as the chief secretary.

The management of spending for supplies was eventually taken away from Sam Hughes and assigned to the newly formed War Purchasing Commission in 1915.

On 17 August 1916, Byng and Hughes had dinner where Hughes announced in his typical bombastic way that he never made a mistake and would hold the power of promotion within the Canadian Corps; Byng in reply stated that as a corps commander he had the power of promotion, that he would inform Hughes before any making promotions as a courtesy, and would resign if Hughes continued his interference with his command in the same way he had with Alderson.

Byng diplomatically told Sam Hughes he had not appointed his son because the "Canadians deserved and expected the best leaders available".

Byng wrote to Borden to say that he would not tolerate political interference in his corps, and he would resign if the younger Sam Hughes was given the command of the 2nd Division rather than Burstall, who did indeed receive the appointment.

The creation of the Ministry of Overseas Military Forces to run the CEF was a major reduction in Sam Hughes's power, causing him to rage and threaten Borden.

Borden's patience with Sam Hughes finally broke, and he dismissed him from the cabinet on 9 November 1916.

Sam Hughes's firing from the cabinet was greeted with relief by the rest of cabinet with the deputy prime minister Forster writing in his diary "the nightmare is removed".

An embittered Sam Hughes set out to embarrass Borden in the House of Commons by making accusations that Borden was mismanaging the war effort, though Sam Hughes's determination to not appear unpatriotic imposed some limits on his willingness to attack the government.

In January 1917, Sam Hughes floated another plan for Beaverbrook to use his influence with David Lloyd George, by then British prime minister, to have him in turn use his influence with King George V to have Sam Hughes appointed to the Privy Council.

When Currie replaced Byng as the commander of the Canadian Corps, Sam Hughes wrote to him, saying it was time for his son to command the 1st Division.

The Canadian historian Tim Cook wrote by 1917 Sam Hughes was losing his mind as he "appeared to be suffering from some form of nascent dementia".

Sam Hughes was against the idea of the Union government, saying at a Tory caucus meeting that a Union government would "forever wipe out" the Conservative Party.

Sam Hughes saw a coalition government as being a hostile takeover of the Conservative Party by the Liberals.

Three weeks before the election, Sam Hughes finally declared his support for the Union government, which led the Unionist candidate to drop out in favour of Sam Hughes.

At least part of the motive for the attack on Currie was the failure of the War Party, which led Sam Hughes to make it his life mission to "expose the whole rotten show overseas" to ruin the reputation of Borden.

Sam Hughes was the cause of practically having murdered thousands of men at Lens and Paschendaele [Passchendaele], and it is generally supposed the motive was to prevent the possibility of Turner coming back with the Second Army Corps, and to prevent Garnet from commanding a Division.

In spite of concerns about possible riots, Sam Hughes travelled to Montreal to give a speech attacking Borden for not conscripting what he claimed were 700,000 young men all across Canada.

Sam Hughes's speeches attacking Borden in Toronto and Montreal were well received by his audiences.

The news of the Armistice on 11 November 1918 was ill-received by Sam Hughes, who felt that Currie had stolen the glory of victory was rightfully his.

In December 1918, Currie learned from friends in Canada that Sam Hughes was telling anybody who would listen that he was "a murderer, a coward, a drunkard and almost everything else that is bad and vile".

On 4 March 1919, in a speech before the Commons, Sam Hughes accused Currie of "needlessly sacrificing the lives of Canadian soldiers".

In particular, Sam Hughes made much of the Second Battle of Mons in November 1918, claiming that Currie had only attacked Mons to have the Canadian Corps end the war for the British Empire where it began.

Sam Hughes always attacked Currie in speeches in the Commons, where criminal and civil law did not apply, ensuring he did not need fear a libel suit or a criminal charges for selectively quoting from official documents that were still classified as secret.

Sam Hughes's speech accusing Currie of "murder" left most Canadians at the time "stunned".

Sam Hughes may have restrained himself as the fact he prevented criminal charges from being laid against Currie in 1915 would have left himself open to charges of obstruction of justice and abuse of his powers as defence minister.

Currie never responded publicly to these attacks, out of the fear that Sam Hughes might reveal that he had stolen $10,000 from his regiment in Victoria, but he was greatly wounded and hurt.

Sam Hughes returned to his home in the forests of Victoria County, which had been built to resemble a luxurious hunting lodge.

Sam Hughes died of pernicious anaemia, aged sixty-eight, in August 1921, and was survived by his son, Garnet Hughes, who served in the First World War, and his grandson, Samuel Hughes, who was a field historian in the Second World War and later a judge.

At the Riverside Cemetery, Sam Hughes's coffin was placed into the earth while bugler Arthur Rhodes winner of the Military Medal played The Last Post and artillery guns fired 15 salutes.

Soldier, journalist, imperialist and Member of Parliament for Lindsay, Ontario from 1892 to 1921, Sam Hughes helped to create a distinctively Canadian Army.

Sir Sam Hughes is listed on the WW1 Memorial Cenotaph in front of the Lindsay Public Library.