1.

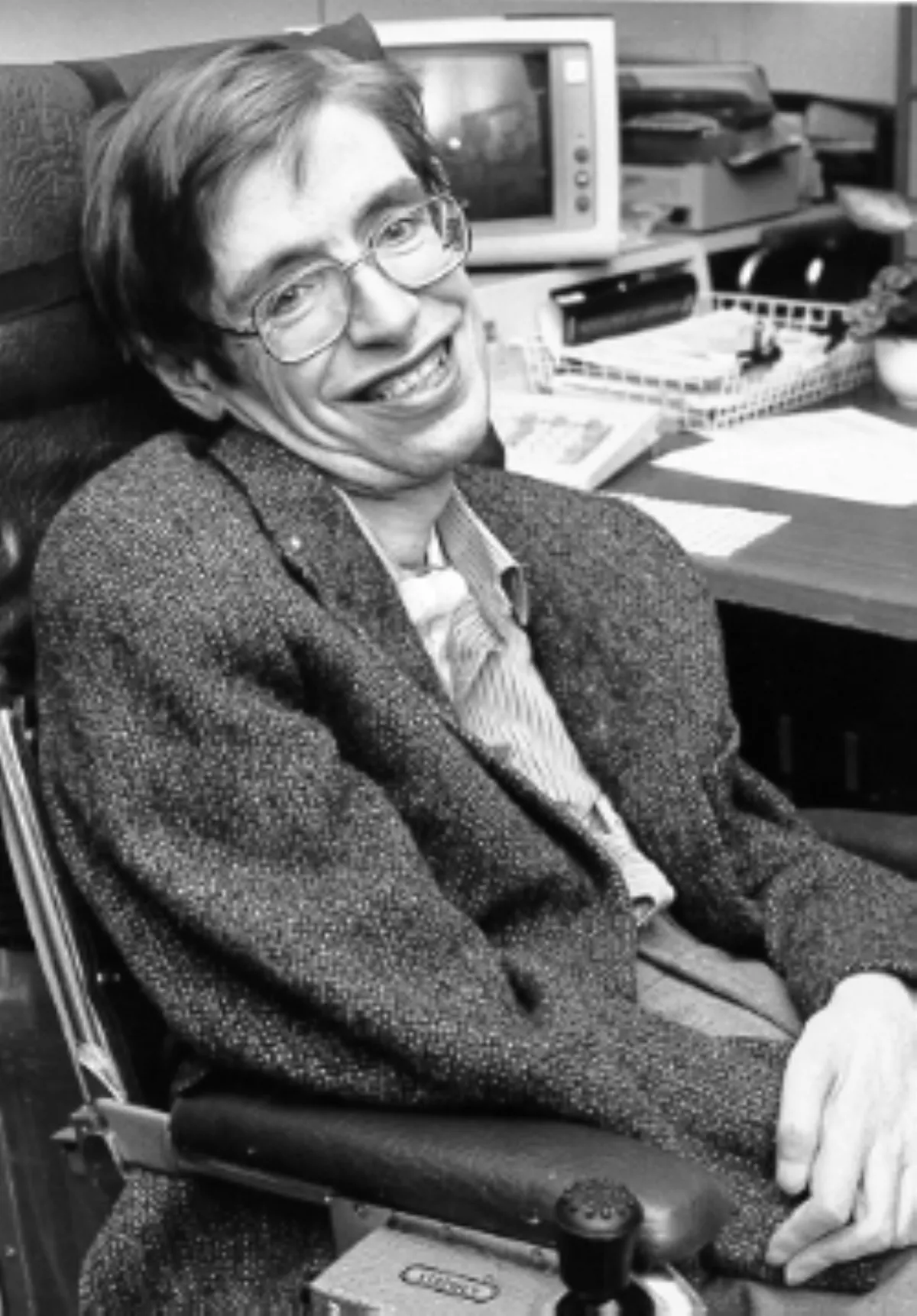

1. Stephen William Hawking was an English theoretical physicist, cosmologist, and author who was director of research at the Centre for Theoretical Cosmology at the University of Cambridge.

1.

1. Stephen William Hawking was an English theoretical physicist, cosmologist, and author who was director of research at the Centre for Theoretical Cosmology at the University of Cambridge.

In 1963, at age 21, Stephen Hawking was diagnosed with an early-onset slow-progressing form of motor neurone disease that gradually, over decades, paralysed him.

Stephen Hawking was the first to set out a theory of cosmology explained by a union of the general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics.

Stephen Hawking was a vigorous supporter of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Stephen Hawking introduced the notion of a micro black hole.

Stephen Hawking achieved commercial success with several works of popular science in which he discussed his theories and cosmology in general.

Stephen Hawking was a Fellow of the Royal Society, a lifetime member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States.

In 2002, Stephen Hawking was ranked number 25 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.

Stephen Hawking died in 2018 at the age of 76, having lived more than 50 years following his diagnosis of motor neurone disease.

Stephen Hawking was born on 8 January 1942 in Oxford to Frank and Isobel Eileen Stephen Hawking.

Stephen Hawking's mother was born into a family of doctors in Glasgow, Scotland.

In 1950, when Stephen Hawking's father became head of the division of parasitology at the National Institute for Medical Research, the family moved to St Albans, Hertfordshire.

Stephen Hawking began his schooling at the Byron House School in Highgate, London.

Stephen Hawking later blamed its "progressive methods" for his failure to learn to read while at the school.

In St Albans, the eight-year-old Stephen Hawking attended St Albans High School for Girls for a few months.

Stephen Hawking's father wanted his son to attend Westminster School, but the 13-year-old Stephen Hawking was ill on the day of the scholarship examination.

Stephen Hawking's father advised him to study medicine, concerned that there were few jobs for mathematics graduates.

Stephen Hawking wanted his son to attend University College, Oxford, his own alma mater.

Stephen Hawking began his university education at University College, Oxford, in October 1959 at the age of 17.

Stephen Hawking developed into a popular, lively and witty college member, interested in classical music and science fiction.

The rowing coach at the time noted that Stephen Hawking cultivated a daredevil image, steering his crew on risky courses that led to damaged boats.

Stephen Hawking estimated that he studied about 1,000 hours during his three years at Oxford.

Stephen Hawking was concerned that he was viewed as a lazy and difficult student.

Stephen Hawking was initially disappointed to find that he had been assigned Dennis William Sciama, one of the founders of modern cosmology, as a supervisor rather than the noted astronomer Fred Hoyle, and he found his training in mathematics inadequate for work in general relativity and cosmology.

Stephen Hawking's disease progressed more slowly than doctors had predicted.

Stephen Hawking started developing a reputation for brilliance and brashness when he publicly challenged the work of Hoyle and his student Jayant Narlikar at a lecture in June 1964.

When Stephen Hawking began his doctoral studies, there was much debate in the physics community about the prevailing theories of the creation of the universe: the Big Bang and Steady State theories.

In 1969, Stephen Hawking accepted a specially created Fellowship for Distinction in Science to remain at Caius.

In 1970, Stephen Hawking postulated what became known as the second law of black hole dynamics, that the event horizon of a black hole can never get smaller.

Stephen Hawking's essay titled "Black Holes" won the Gravity Research Foundation Award in January 1971.

Stephen Hawking was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1974, a few weeks after the announcement of Stephen Hawking radiation.

Stephen Hawking was appointed to the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Visiting Professorship at the California Institute of Technology in 1974.

Stephen Hawking worked with a friend on the faculty, Kip Thorne, and engaged him in a scientific wager about whether the X-ray source Cygnus X-1 was a black hole.

Stephen Hawking acknowledged that he had lost the bet in 1990, a bet that was the first of several he was to make with Thorne and others.

Stephen Hawking had maintained ties to Caltech, spending a month there almost every year since this first visit.

Stephen Hawking returned to Cambridge in 1975 to a more academically senior post, as reader in gravitational physics.

Stephen Hawking was appointed a professor with a chair in gravitational physics in 1977.

In 1979, Stephen Hawking was elected Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge.

Stephen Hawking's promotion coincided with a health-crisis which led to his accepting, albeit reluctantly, some nursing services at home.

Stephen Hawking began a new line of quantum-theory research into the origin of the universe.

One of the first messages Stephen Hawking produced with his speech-generating device was a request for his assistant to help him finish writing A Brief History of Time.

Stephen Hawking travelled extensively to promote his work, and enjoyed partying into the late hours.

Some colleagues were resentful of the attention Stephen Hawking received, feeling it was due to his disability.

Stephen Hawking received further academic recognition, including five more honorary degrees, the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society, the Paul Dirac Medal and, jointly with Penrose, the prestigious Wolf Prize.

Stephen Hawking reportedly declined a knighthood in the late 1990s in objection to the UK's science funding policy.

Stephen Hawking pursued his work in physics: in 1993 he co-edited a book on Euclidean quantum gravity with Gary Gibbons and published a collected edition of his own articles on black holes and the Big Bang.

Thorne and Stephen Hawking argued that since general relativity made it impossible for black holes to radiate and lose information, the mass-energy and information carried by Stephen Hawking radiation must be "new", and not from inside the black hole event horizon.

Stephen Hawking maintained his public profile, including bringing science to a wider audience.

Stephen Hawking had wanted the film to be scientific rather than biographical, but he was persuaded otherwise.

Stephen Hawking continued his writings for a popular audience, publishing The Universe in a Nutshell in 2001, and A Briefer History of Time, which he wrote in 2005 with Leonard Mlodinow to update his earlier works with the aim of making them accessible to a wider audience, and God Created the Integers, which appeared in 2006.

Stephen Hawking continued to travel widely, including trips to Chile, Easter Island, South Africa, Spain, Canada, and numerous trips to the United States.

For practical reasons related to his disability, Stephen Hawking increasingly travelled by private jet, and by 2011 that had become his only mode of international travel.

Stephen Hawking quickly conceded that he had lost his bet and said that Higgs should win the Nobel Prize for Physics, which he did in 2013.

Stephen Hawking was awarded the Copley Medal from the Royal Society, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which is America's highest civilian honour, and the Russian Special Fundamental Physics Prize.

Several buildings have been named after him, including the Stephen W Hawking Science Museum in San Salvador, ElSalvador, the Stephen Hawking Building in Cambridge, and the Stephen Hawking Centre at the Perimeter Institute in Canada.

On 28 June 2009, as a tongue-in-cheek test of his 1992 conjecture that travel into the past is effectively impossible, Stephen Hawking held a party open to all, complete with hors d'oeuvres and iced champagne, but publicised the party only after it was over so that only time-travellers would know to attend; as expected, nobody showed up to the party.

On 20 July 2015, Stephen Hawking helped launch Breakthrough Initiatives, an effort to search for extraterrestrial life.

In July 2017, Stephen Hawking was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Imperial College London.

Stephen Hawking met his future wife, Jane Wilde, at a party in 1962.

In October 1964, the couple became engaged to marry, aware of the potential challenges that lay ahead due to Stephen Hawking's shortened life expectancy and physical limitations.

Stephen Hawking later said that the engagement gave him "something to live for".

The couple resided in Cambridge, within Stephen Hawking's walking distance to the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics.

Stephen Hawking's disabilities meant that the responsibilities of home and family rested firmly on his wife's shoulders, leaving him more time to think about physics.

Stephen Hawking accepted, and Bernard Carr travelled with them as the first of many students who fulfilled this role.

Stephen Hawking returned to Cambridge in 1975 to a new home and a new job, as reader.

Don Page, with whom Stephen Hawking had begun a close friendship at Caltech, arrived to work as the live-in graduate student assistant.

In February 1990, Stephen Hawking told Jane that he was leaving her for Mason and departed the family home.

In 1999, Jane Stephen Hawking published a memoir, Music to Move the Stars, describing her marriage to Stephen Hawking and its breakdown.

Police investigations took place, but were closed as Stephen Hawking refused to make a complaint.

Stephen Hawking had a rare early-onset, slow-progressing form of motor neurone disease, which gradually paralysed him over decades.

Stephen Hawking had experienced increasing clumsiness during his final year at Oxford, including a fall on some stairs and difficulties when rowing.

Stephen Hawking's family noticed the changes when he returned home for Christmas, and medical investigations were begun.

The MND diagnosis came when Stephen Hawking was 21, in 1963.

Stephen Hawking was fiercely independent and unwilling to accept help or make concessions for his disabilities.

Stephen Hawking preferred to be regarded as "a scientist first, popular science writer second, and, in all the ways that matter, a normal human being with the same desires, drives, dreams, and ambitions as the next person".

Stephen Hawking was a popular and witty colleague, but his illness, as well as his reputation for brashness, distanced him from some.

When Stephen Hawking first began using a wheelchair he was using standard motorised models.

Stephen Hawking continued to use this type of chair until the early 1990s, at which time his ability to use his hands to drive a wheelchair deteriorated.

Stephen Hawking used a variety of different chairs from that time, including a DragonMobility Dragon elevating powerchair from 2007, as shown in the April 2008 photo of Stephen Hawking attending NASA's 50th anniversary; a Permobil C350 from 2014; and then a Permobil F3 from 2016.

Stephen Hawking's speech deteriorated, and by the late 1970s he could be understood by only his family and closest friends.

In general, Stephen Hawking had ambivalent feelings about his role as a disability rights champion: while wanting to help others, he sought to detach himself from his illness and its challenges.

Stephen Hawking refused, but the consequence was a tracheotomy, which required round-the-clock nursing care and caused the loss of what remained of his speech.

Originally, Stephen Hawking activated a switch using his hand and could produce up to 15 words per minute.

Stephen Hawking gradually lost the use of his hand, and in 2005 he began to control his communication device with movements of his cheek muscles, with a rate of about one word per minute.

Stephen Hawking had an easier time adapting to the new system, which was further developed after inputting large amounts of Stephen Hawking's papers and other written materials and uses predictive software similar to other smartphone keyboards.

In 1999, Stephen Hawking was awarded the Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize of the American Physical Society.

In late 2006, Stephen Hawking revealed in a BBC interview that one of his greatest unfulfilled desires was to travel to space.

Stephen Hawking died at his home in Cambridge on 14 March 2018, at the age of 76.

Stephen Hawking was eulogised by figures in science, entertainment, politics, and other areas.

At Google's Zeitgeist Conference in 2011, Stephen Hawking said that "philosophy is dead".

Stephen Hawking said that philosophical problems can be answered by science, particularly new scientific theories which "lead us to a new and very different picture of the universe and our place in it".

Stephen Hawking stated: "I regard it as almost inevitable that either a nuclear confrontation or environmental catastrophe will cripple the Earth at some point in the next 1,000 years".

Stephen Hawking viewed spaceflight and the colonisation of space as necessary for the future of humanity.

Stephen Hawking stated that, given the vastness of the universe, aliens likely exist, but that contact with them should be avoided.

Stephen Hawking warned that aliens might pillage Earth for resources.

Stephen Hawking considered that the enormous wealth generated by machines needs to be redistributed to prevent exacerbated economic inequality.

Stephen Hawking was later scheduled to appear as the keynote speaker at a 2017 Humanists UK conference.

Stephen Hawking recorded a tribute for the 2000 Democratic presidential candidate Al Gore, called the 2003 invasion of Iraq a "war crime", campaigned for nuclear disarmament, and supported stem cell research, universal health care, and action to prevent climate change.

Stephen Hawking believed a United Kingdom withdrawal from the European Union would damage the UK's contribution to science as modern research needs international collaboration, and that free movement of people in Europe encourages the spread of ideas.

Stephen Hawking was greatly concerned over health care, and maintained that without the UK National Health Service, he could not have survived into his 70s.

Stephen Hawking accused Jeremy Hunt of cherry picking evidence which Stephen Hawking maintained debased science.

Stephen Hawking feared Donald Trump's policies on global warming could endanger the planet and make global warming irreversible.

At the release party for the home video version of the A Brief History of Time, Leonard Nimoy, who had played Spock on Star Trek, learned that Stephen Hawking was interested in appearing on the show.

Nimoy made the necessary contact, and Stephen Hawking played a holographic simulation of himself in an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation in 1993.

Stephen Hawking guest-starred in Futurama and had a recurring role in The Big Bang Theory.

Stephen Hawking allowed the use of his copyrighted voice in the biographical 2014 film The Theory of Everything, in which he was portrayed by Eddie Redmayne in an Academy Award-winning role.

Stephen Hawking was featured at the Monty Python Live show in 2014.

Stephen Hawking was shown to sing an extended version of the "Galaxy Song", after running down Brian Cox with his wheelchair, in a pre-recorded video.

Stephen Hawking used his fame to advertise products, including a wheelchair, National Savings, British Telecom, Specsavers, Egg Banking, and Go Compare.

Broadcast in March 2018 just a week or two before his death, Stephen Hawking was the voice of The Book Mark II on The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy radio series, and he was the guest of Neil deGrasse Tyson on StarTalk.

Stephen Hawking has made major contributions to the field of general relativity.

In collaboration with G Ellis, Hawking is the author of an impressive and original treatise on "Space-time in the Large".

Stephen Hawking was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the United States National Academy of Sciences.

Stephen Hawking received the 2015 BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Basic Sciences shared with Viatcheslav Mukhanov for discovering that the galaxies were formed from quantum fluctuations in the early Universe.

At the 2016 Pride of Britain Awards, Stephen Hawking received the lifetime achievement award "for his contribution to science and British culture".

Stephen Hawking himself accepted the inaugural fellowship, and he delivered the first Stephen Hawking Lecture in his last public appearance before his death.

Stephen Hawking was a member of the advisory board of the Starmus Festival, and had a major role in acknowledging and promoting science communication.

The Stephen Hawking Medal for Science Communication is an annual award initiated in 2016 to honour members of the arts community for contributions that help build awareness of science.