1.

1. The son of Govan Mbeki, an ANC intellectual, Mbeki has been involved in ANC politics since 1956, when he joined the ANC Youth League, and has been a member of the party's National Executive Committee since 1975.

1.

1. The son of Govan Mbeki, an ANC intellectual, Mbeki has been involved in ANC politics since 1956, when he joined the ANC Youth League, and has been a member of the party's National Executive Committee since 1975.

Thabo Mbeki rose through the organisation in its information and publicity section and as Oliver Tambo's protege, but he was an experienced diplomat, serving as the ANC's official representative in several of its African outposts.

Thabo Mbeki was an early advocate for and leader of the diplomatic engagements which led to the negotiations to end apartheid.

Thabo Mbeki was the central architect of the New Partnership for Africa's Development and, as the inaugural chairperson of the African Union, spearheaded the introduction of the African Peer Review Mechanism.

Thabo Mbeki's government did not introduce a national mother-to-child transmission prevention programme until 2002, when it was mandated by the Constitutional Court, nor did it make antiretroviral therapy available in the public healthcare system until late 2003.

The ANC's decision to "recall" Thabo Mbeki was understood to be linked to a High Court judgement, handed down earlier that month, in which judge Chris Nicholson had alleged improper political interference in the National Prosecuting Authority and specifically in the corruption charges against Zuma.

Nicholson's judgement was overturned by the Supreme Court of Appeal in January 2009, by which time Thabo Mbeki had been replaced as president by Kgalema Motlanthe.

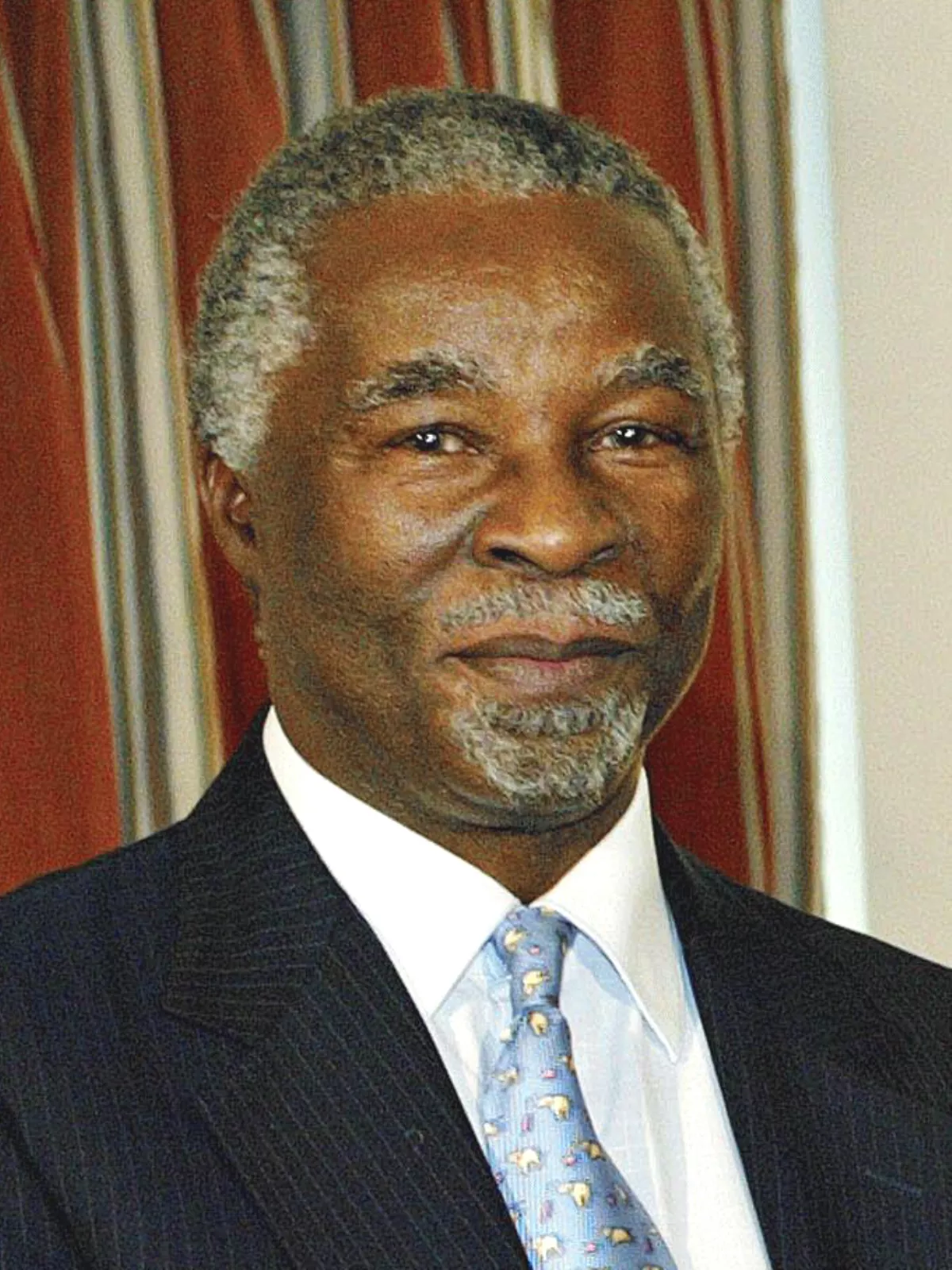

Thabo Mbeki was born on 18 June 1942 in Mbewuleni, a small village in the former homeland of Transkei, now part of the Eastern Cape.

Thabo Mbeki's parents were Epainette, a trained teacher, and Govan, a shopkeeper, teacher, journalist, and senior activist in the African National Congress and the South African Communist Party.

The couple had met in Durban, where Epainette had become the second black woman to join the SACP ; however, while Thabo Mbeki was a child, his family was separated when Govan moved alone to Ladismith for a teaching job.

Thabo Mbeki has said that he was "born into the struggle", and recalls that his childhood home was decorated with portraits of Karl Marx and Mahatma Gandhi.

Thabo Mbeki began attending school in 1948, the same year that the National Party was elected with a mandate to legislate apartheid.

Thabo Mbeki joined the ANC Youth League at age fourteen and in 1958 became the secretary of its Lovedale branch.

Thabo Mbeki nonetheless sat for matric examinations and obtained a second-class pass.

In June 1960, Thabo Mbeki moved to Johannesburg, where he lived in the home of ANC secretary general Duma Nokwe and where he intended to sit for A-level examinations.

The ANC had recently been banned in the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre, but Thabo Mbeki remained highly politically active, becoming national secretary of the African Students' Association, a new youth movement envisaged as replacing the now illegal ANC Youth League.

Thabo Mbeki was detained twice by the police while attempting to leave the country, first in Rustenberg, when the group he was travelling with failed to pass themselves off as a touring football team, and then in Rhodesia.

Thabo Mbeki arrived at the ANC's new headquarters in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in November 1962, and left shortly afterwards for England.

Thabo Mbeki remained active in the SACP, which was very closely allied to the ANC, and in 1967 he was appointed to the editorial board of its official magazine, the African Communist.

Thabo Mbeki was educated at the Lenin Institute, where, because of the secrecy required, he went by the alias "Jack Fortune".

Thabo Mbeki excelled at the institute and in June 1970 was appointed to the Central Committee of the SACP, alongside Chris Hani.

Thabo Mbeki was to fill the post of administrative secretary to the ANC Revolutionary Council, a body newly established to coordinate the political and military efforts of the ANC and SACP.

Thabo Mbeki was later moved to the propaganda section, but continued to attend the council's meetings, and in 1975 he was elected onto the ANC's top decision-making organ, the National Executive Committee.

Between 1975 and 1976, Thabo Mbeki was instrumental in establishing the ANC's frontline base in Swaziland.

Thabo Mbeki was first sent there to assess the political landscape in January 1975, under the cover of attending a UN conference.

Thabo Mbeki made a positive report to the ANC executive, and he was sent back to Swaziland to begin establishing the base.

Thabo Mbeki was responsible for recruiting new MK operatives, for liaising with South African student and labour activists, and for liaising with Inkatha, which was becoming dominant in Natal.

In 1978, Maharaj and Thabo Mbeki argued at a top-level strategic meeting in Luanda, Angola, when Maharaj, who had been tasked with running the political underground, claimed that Thabo Mbeki's records from the Swaziland office were in fact "just an empty folder".

Thabo Mbeki continued to ghostwrite for Tambo, now in a formal capacity.

Thabo Mbeki eschewed the secrecy of earlier years and openly gave interviews and access to American journalists, to the disapproval of some hardline communists.

Thabo Mbeki established some of his own high-level intelligence networks, with key underground operatives reporting directly to him, and Gevisser claims that these led to the initiation of relationships with many of the domestic activists who later became his political allies.

Zuma has said that it was Thabo Mbeki's "drafting skills" which enabled his ascendancy in the ANC and ultimately to the presidency.

In 1980, Thabo Mbeki led the ANC's delegation to Zimbabwe, where the party hoped to establish relations with Robert Mugabe's newly elected government.

However, Thabo Mbeki handed the running of the Salisbury office over to another ANC official, and the deal later collapsed.

Also in 1985, Thabo Mbeki became the ANC's director of the Department of Information and Publicity and coordinated diplomatic campaigns to involve more white South Africans in anti-apartheid activities.

Thabo Mbeki played a major role in turning the international media against apartheid.

Thabo Mbeki played the role of ambassador to the steady flow of delegates from the elite sectors of white South Africa.

Thabo Mbeki was known for his diplomatic style and sophistication.

Thabo Mbeki was appointed head of the ANC's information department in 1984 and then became head of the international department in 1989, reporting directly to Oliver Tambo, then President of the ANC.

In 1985, Thabo Mbeki was a member of a delegation that began meeting secretly with representatives of the South African business community, and in 1989, he led the ANC delegation that conducted secret talks with the South African government.

Thabo Mbeki participated in many of the other important negotiations between the ANC and the government that eventually led to the democratisation of South Africa.

However, at the ANC's 48th National Conference in July 1991, its first national elective conference since 1960, Thabo Mbeki was not elected to any of the "Top Six" leadership positions.

When Tambo died later the same month, Thabo Mbeki succeeded him as ANC national chairperson.

In June 1996, the National Party withdrew from the Government of National Unity and, with the second deputy, de Klerk, having thereby resigned, Thabo Mbeki became the sole deputy president.

Thabo Mbeki took on increasing domestic responsibilities, including executive powers delegated to him by Mandela, to such an extent that Mandela called him "a de facto president".

Mandela had made it clear publicly since early 1995 or earlier that he intended to retire after one term in office, and by then Thabo Mbeki was already seen as his most likely successor.

In December 1997, the ANC's 50th National Conference elected Thabo Mbeki unopposed to succeed Mandela as ANC president.

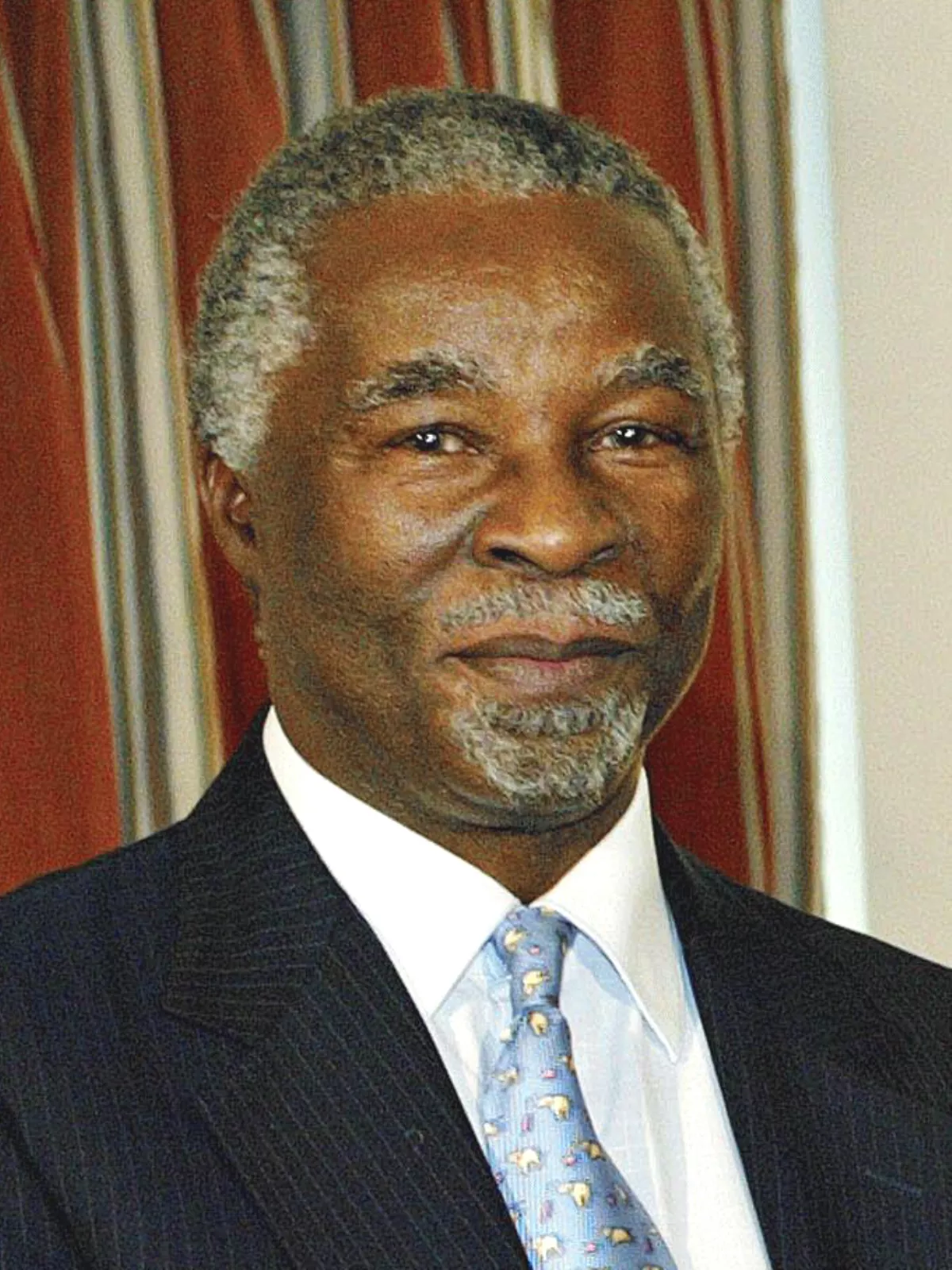

Pursuant to the 1999 national elections, which the ANC won by a significant majority, Thabo Mbeki was elected president of South Africa.

Thabo Mbeki was re-elected for a second term in 2002.

Thabo Mbeki had been highly involved in economic policy as deputy president, especially in spearheading the Growth, Employment and Redistribution programme, which was introduced in 1996 and remained a cornerstone of Thabo Mbeki's administration after 1999.

Thabo Mbeki retained various social democratic programmes and principles, and generally endorsed a mixed economy in South Africa.

Thabo Mbeki advocated for greater solidarity among African countries and, in place of reliance on Western intervention and aid, for greater self-sufficiency for the African continent.

Thabo Mbeki called for Western leaders to address global apartheid and unequal development, most memorably in a speech to the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in August 2002.

Thabo Mbeki was involved in the dissolution of the Organisation of African Unity and its replacement by the African Union, of which he became the inaugural chairperson in 2002, and his government spearheaded the introduction of the AU's African Peer Review Mechanism in 2003.

Thabo Mbeki was twice chairperson of the Southern African Development Community, first from 1999 to 2000 and second, briefly, in 2008.

Outside Africa, Thabo Mbeki was the chairperson of the Non-Aligned Movement between 1999 and 2003 and the chairperson of the Group of 77 + China in 2006.

Thabo Mbeki pursued South-South solidarity in a coalition with India and Brazil under the IBSA Dialogue Forum, which was launched in June 2003 and held its first summit in September 2006.

Indeed, Thabo Mbeki had called for reform at the UN as early as 1999 and 2000.

Thabo Mbeki later told the media that the resolution exceeded the Security Council's mandate, and that its tabling had been illegal in terms of international law.

Thabo Mbeki's presidency coincided with an escalating political and economic crisis in South Africa's neighbour, Zimbabwe, under president Mugabe of ZANU-PF.

Thabo Mbeki was firmly opposed to forcible or manufactured regime change in Zimbabwe, and opposed the use of sanctions.

Thabo Mbeki mediated the negotiations and brokered the resulting power-sharing agreement, signed on 15 September 2008, which retained Mugabe as president but diluted his executive power across posts to be held by opposition leaders.

Thabo Mbeki was viewed as sympathetic to or influenced by the views of a small minority of scientists who challenged the scientific consensus that HIV caused AIDS and that antiretroviral drugs were the most effective means of treatment.

In late 2007, Thabo Mbeki's government announced that the public power utility, Eskom, would introduce electricity rationing or rolling blackouts, commonly known in South Africa as loadshedding.

Some commentators argued that Thabo Mbeki's government had failed to acknowledge or sufficiently to address growing xenophobia in South Africa in the years preceding the attacks.

In June 2005, Thabo Mbeki removed Zuma from his post as national deputy president, after Zuma's associate Schabir Shaik was convicted of making corrupt payments to Zuma in relation to the 1999 Arms Deal.

Zuma drew substantial support from the left wing of the party, especially through the ANC Youth League and the ANC's partners in the Tripartite Alliance, the South African Communist Party and COSATU, with whom Thabo Mbeki's relationship was extremely poor.

Thabo Mbeki found that the charges were unlawful on the procedural grounds that the NPA had not given Zuma adequate opportunity to make representations.

However, shortly after Nicholson delivered his judgement and months before the appeal was heard, the Zuma-aligned ANC National Executive Committee, as elected at the Polokwane conference, "recalled" Thabo Mbeki, asking him to resign as national president.

Thabo Mbeki began again to appear at ANC events and to comment on ANC politics from around 2011.

Motlanthe asked Thabo Mbeki to remain in his role as mediator in Zimbabwe after his resignation in 2008, and he later returned to Zimbabwe, in 2020, to mediate a further political dispute.

Thabo Mbeki continued to chair the long-serving AU High-level Implementation Panel for Sudan and South Sudan, which in 2016 brokered an agreement between warring Sudanese parties to begin peace negotiations.

The Thabo Mbeki Foundation was launched on 10 October 2010, ahead of a three-day conference.

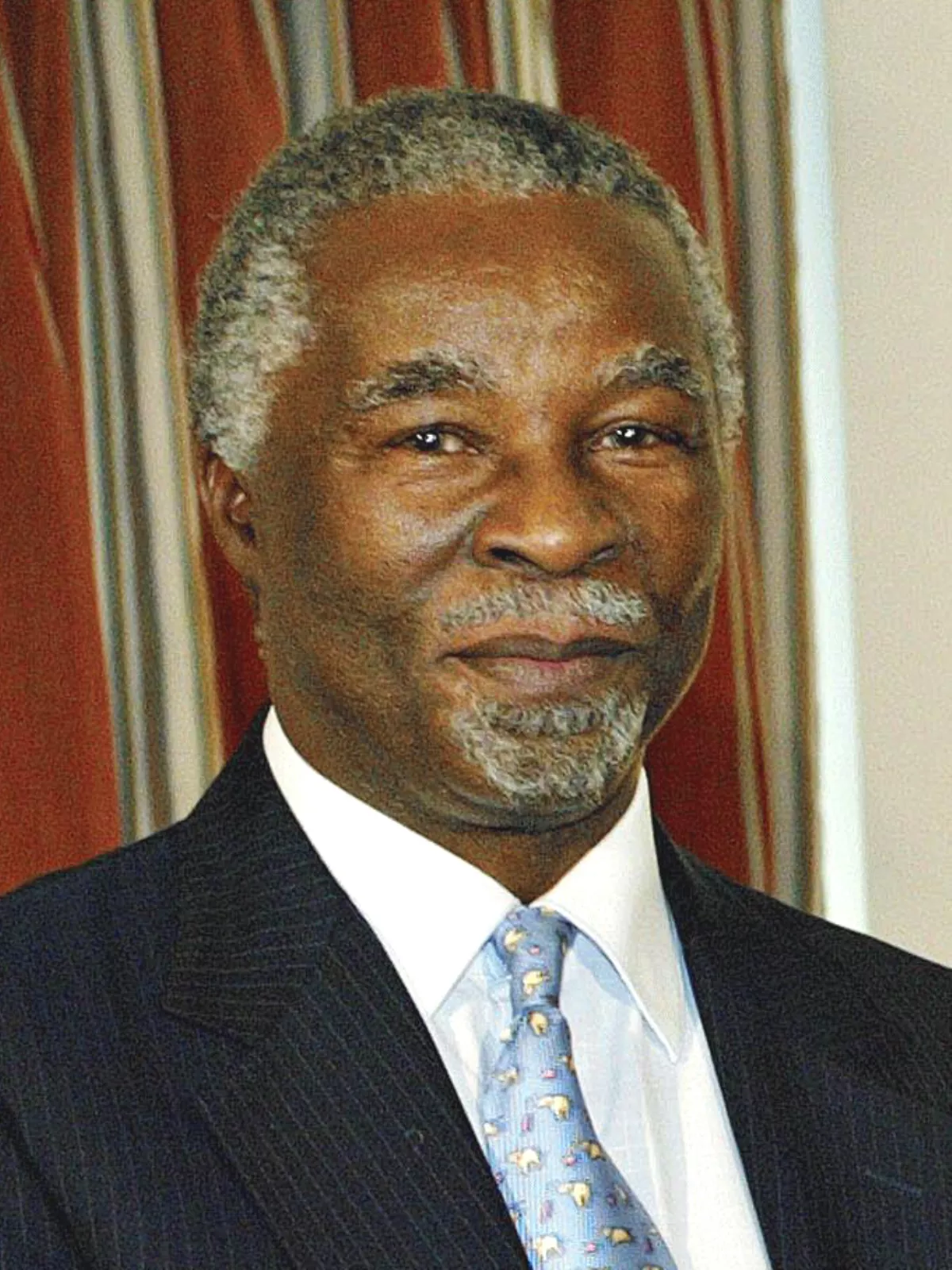

Thabo Mbeki has sometimes been characterised as remote and academic, although in his second campaign for the Presidency in 2004, many observers described him as finally relaxing into more traditional ways of campaigning, sometimes dancing at events and even kissing babies.

Thabo Mbeki used his weekly column in the ANC newsletter ANC Today, to produce discussions on a variety of topics.

Thabo Mbeki sometimes used his column to deliver pointed invective against political opponents, and at other times used it as a kind of professor of political theory, educating ANC cadres on the intellectual justifications for African National Congress policy.

Indeed, in initiating his columns, Thabo Mbeki stated his view that the bulk of South African media sources did not speak for or to the South African majority, and stated his intent to use ANC Today to speak directly to his constituents rather than through the media.

Thabo Mbeki appears to have been at ease with the Internet and willing to quote from it.

President Thabo Mbeki said the suggestion of unacceptably high violent crime appeared to be an acceptance by the panel of what he called "a populist view".

In 2004 the Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town, Desmond Tutu, criticised President Thabo Mbeki for surrounding himself with "yes-men", not doing enough to improve the position of the poor and for promoting economic policies that only benefited a small black elite.

Thabo Mbeki accused Mbeki and the ANC of suppressing public debate.

Thabo Mbeki responded that Tutu had never been an ANC member and defended the debates that took place within ANC branches and other public forums.

On 10 October 2024, Thabo Mbeki wrote a letter to Mr Matome Chiloane, Member of the Executive for the Gauteng Education Department, criticizing the GED's handling of an incident of alleged racism at Pretoria High School for Girls.

In October 1959, Thabo Mbeki had a son, Monwabisi Kwanda, with Olive Mpahlwa, a childhood friend which whom he had struck up a romance while at Lovedale.

Thabo Mbeki was last seen by his family in 1981 and is presumed to have died in exile, but the circumstances of his death remain unknown.

Thabo Mbeki had spent his adolescence in Lesotho and was an activist in the Basutoland Congress Party and its Lesotho Liberation Army.

Thabo Mbeki's only living sibling, Moeletsi, was educated abroad and is a prominent economist.

Thabo Mbeki married Zanele Dlamini Thabo Mbeki in 1974, a social worker from Alexandra whom he met in London before his departure for Moscow.

Thabo Mbeki has received many honorary degrees from South African and foreign universities.

Thabo Mbeki received an honorary doctorate in business administration from the Arthur D Little Institute, Boston, in 1994.

Thabo Mbeki was awarded an honorary doctorate from Rand Afrikaans University in 1999.

In 2007, Thabo Mbeki was made a Knight of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem at St George's Cathedral in Cape Town by the current grand prior, Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester.

Thabo Mbeki was awarded the Good Governance Award in 1997 by the US-based Corporate Council on Africa.

Thabo Mbeki received the Newsmaker of the year award from Pretoria News Press Association in 2000 and repeated the honour in 2008, this time under the auspices of media research company Monitoring South Africa.

Thabo Mbeki was awarded the Peace and Reconciliation Award at the Gandhi Awards for Reconciliation in Durban in 2003.

In 2004, Thabo Mbeki was awarded the Good Brother Award by Washington, DC's National Congress of Black Women for his commitment to gender equality and the emancipation of women in South Africa.

In 2007 Thabo Mbeki was awarded the Confederation of African Football's Order of Merit for his contribution to football on the continent.