1.

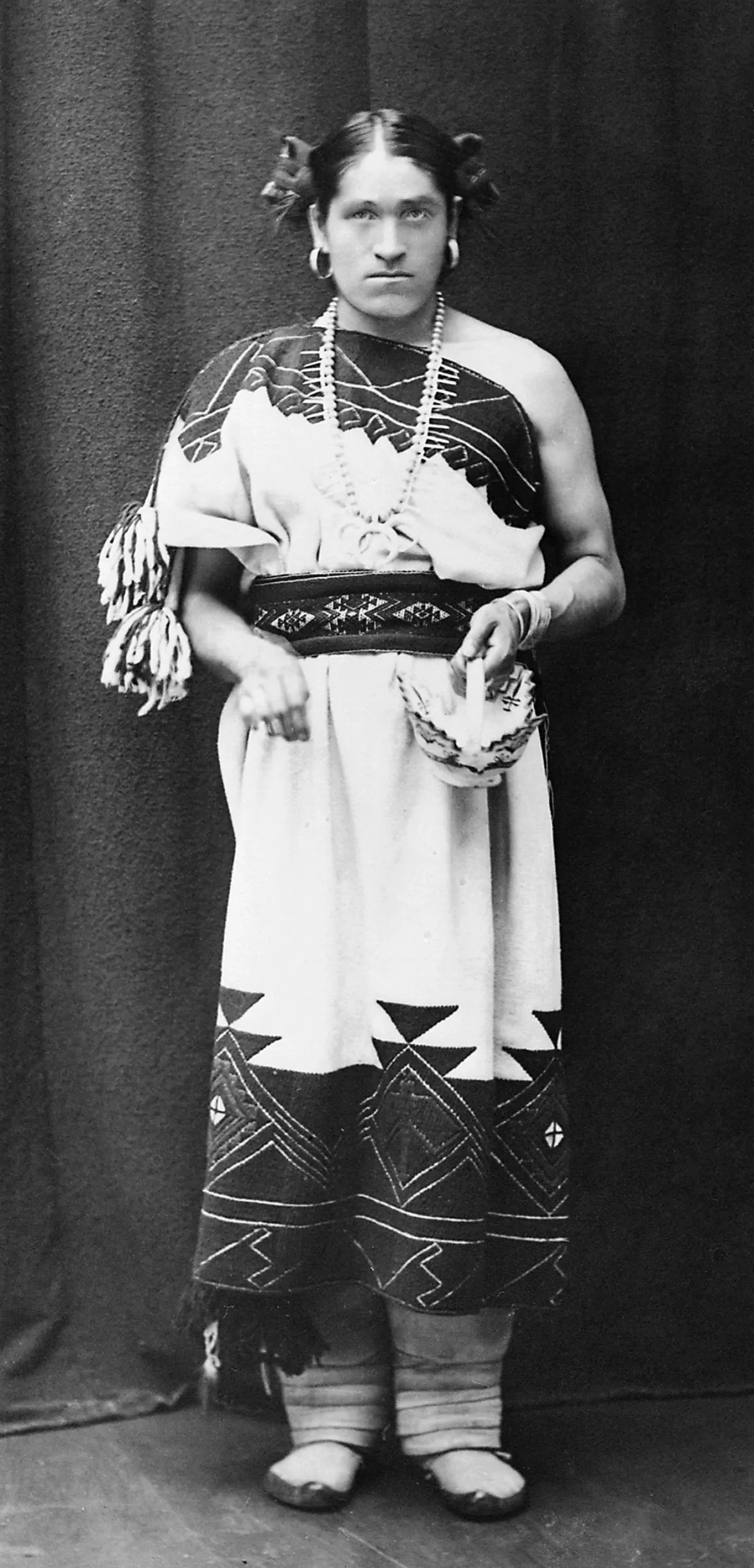

1. We'wha's adopted family was one of the richest and most influential in Zuni culture, placing We'wha in a privileged position to assert their ceremonial importance as a lhamana.

1.

1. We'wha's adopted family was one of the richest and most influential in Zuni culture, placing We'wha in a privileged position to assert their ceremonial importance as a lhamana.

In 1886, We'wha was part of the Zuni delegation to Washington, DC; during that visit, We'wha met President Grover Cleveland.

For instance, We'wha belonged to the male kachina society, a group who performed ritual dances in ceremonial masks.

Stevenson wrote down her observations of We'wha, using both male and female pronouns at different points in time, writing, "She performs masculine religious and judicial functions at the same time that she performs feminine duties, tending to laundry and the garden".

Friends and relatives have used both male and female pronouns for We'wha, depending on stage of life and current occupation.

We'wha was born around 1849 in New Mexico as a member of the Zuni people.

The year of We'wha's birth was the first year the Zuni had interactions with the Americans, and they initially agreed to ally with the colonists in some territorial battles against their traditional rivals the Navajo and Apache.

The colonists brought smallpox to the village and in 1853 both of We'wha's parents died from the new illness.

We'wha remained a member of her mother's tribal clan known as the donashi:kwe.

We'wha retained ceremonial ties to his father's clan, bichi:kwe.

At this point, We'wha would have been in his thirties.

The Presbyterian minister and medical doctor assigned to We'wha's tribe was a man named Taylor F Ealy, who arrived at the village with his wife, two daughters, and an assistant teacher on October 12,1878.

We'wha helped Mrs Ealy care for her two small daughters, along with various teaching responsibilities and housework.

Matilda Coxe Stevenson and We'wha met each other in 1879, while they were working with Mrs Ealy.

Stevenson wrote that We'wha was very friendly to outsiders and willing to learn English.

We'wha taught them how to wash clothes using this stronger, chemical soap and soon We'wha began washing quantities of clothes for the members of the Protestant mission, earning silver dollars for this service.

We'wha then decided to move to Fort Wingate and wash for the soldiers as well as the captain's family.

We'wha began to extend the business past the fort, and wash for white settlers as well.

We'wha was hired by Stevenson to make Zuni religious pottery that would later be displayed in the National Museum in Washington, DC We'wha was a very accomplished potter, and followed the strict religious protocols that went with making Zuni pottery.

We'wha was a part of Washington society alongside the Stevensons during the trip and attended various events.

One of the more notable events was We'wha meeting President Grover Cleveland on June 24,1886.

We'wha drew special attention from the United States government and press.

We'wha drew this attention because most Americans believed We'wha to be a woman, and it was unusual for the United States to receive female Native American delegates.

We'wha had their own goals in their visit to the capital.

But, six years after their time spent in Washington, We'wha served a month in prison.

The reason We'wha spent time in prison has been questioned as some attribute it to witchcraft.

In 1896, We'wha's family was selected to host the annual Sha'lako festival and he worked to ensure everything was prepared.

We'wha said but a few words and then sank back in her chair.

We'wha has a page on The National Women's History Museum's website, published recently as June 2021.

Some spellings and ways in which We'wha was referred to include: We'wha, We:wa, Zuni Princess, and many other titles.

Will Roscoe, the scholar who has written the most about We'wha, uses primarily masculine pronouns.

The National Women's History Museum's page on We'wha opts to use the gender-neutral pronoun "they", arguing that the Zuni recognized lhamana as culturally and socially distinct from both men and women, so neither masculine nor feminine pronouns are appropriate.