1.

1. Wiley Rutledge participated in several noteworthy cases involving the intersection of individual freedoms and the government's wartime powers.

1.

1. Wiley Rutledge participated in several noteworthy cases involving the intersection of individual freedoms and the government's wartime powers.

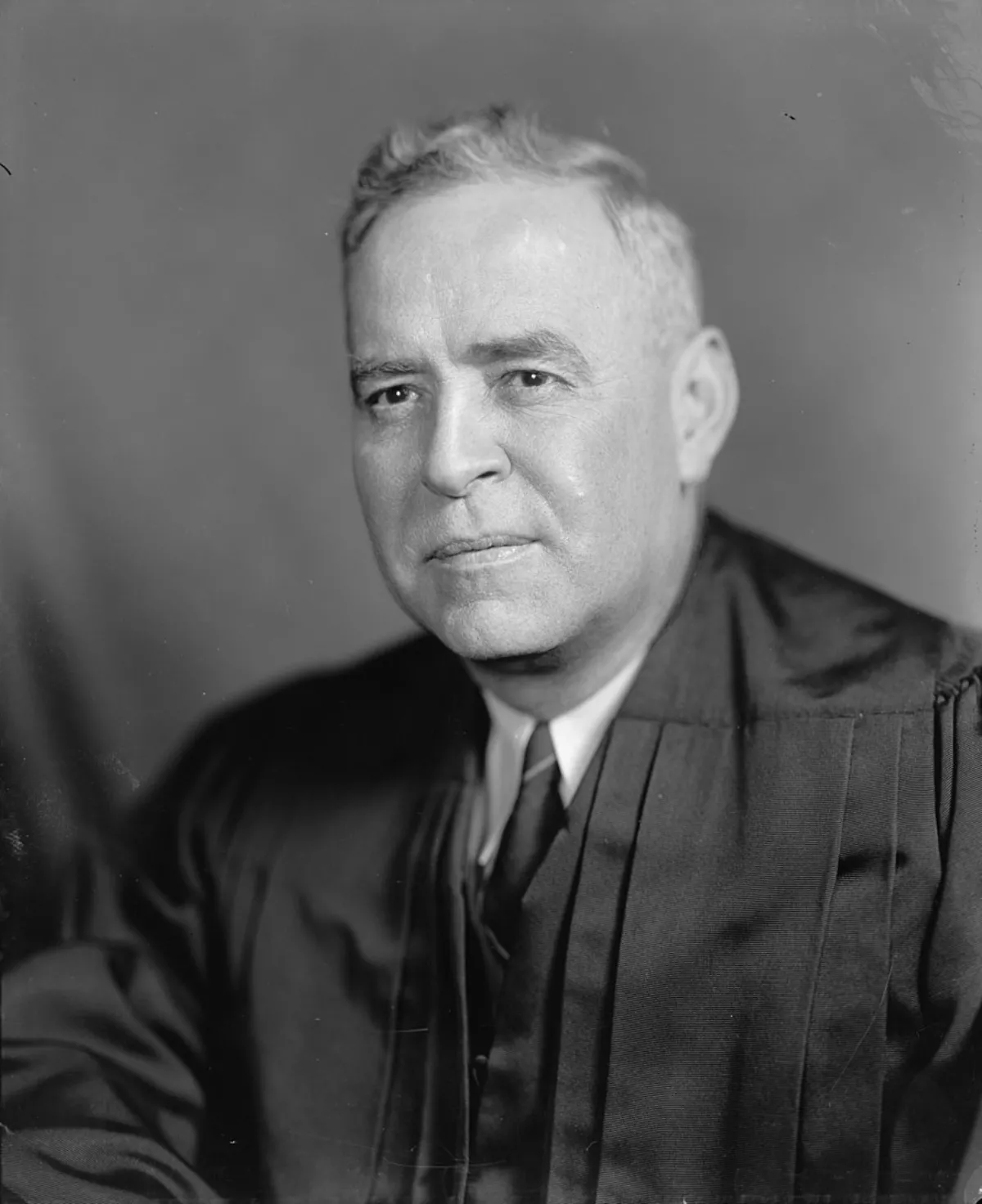

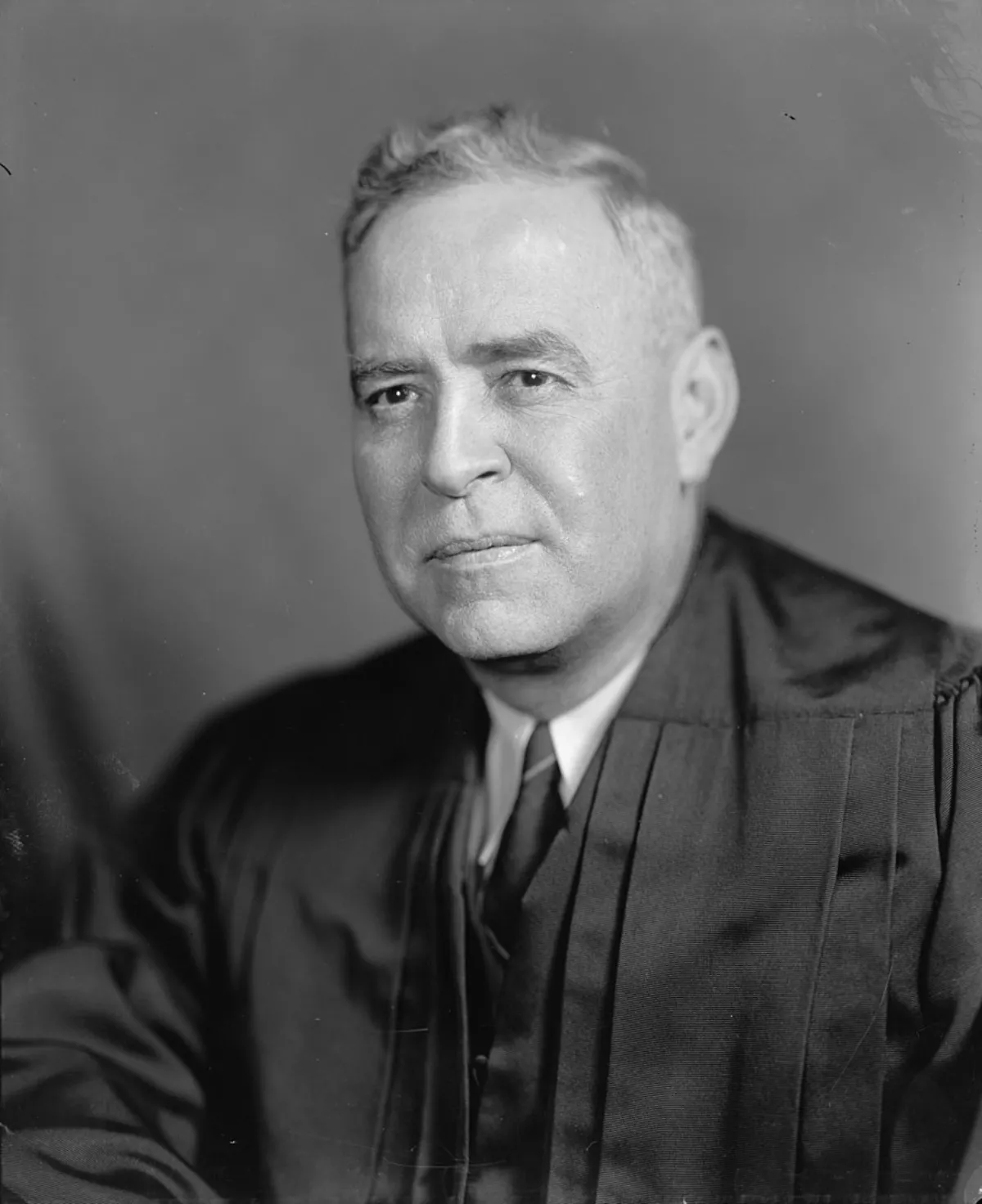

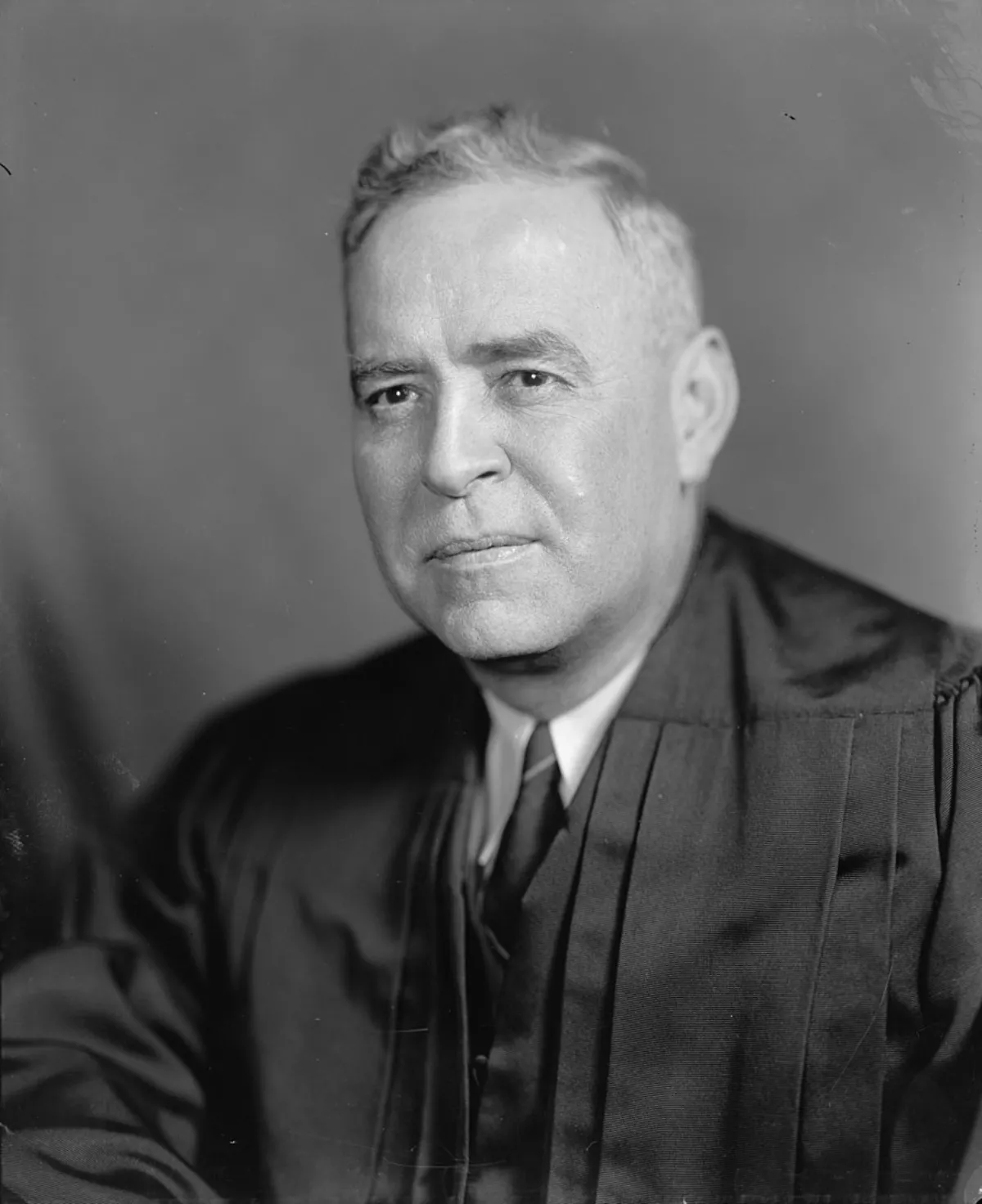

Wiley Rutledge served on the Court until his death at the age of fifty-five.

Wiley Rutledge briefly practiced law in Boulder, Colorado, before accepting a position on the faculty of the University of Colorado Law School.

Wiley Rutledge taught law at the Washington University School of Law in St Louis, Missouri, of which he became the dean; he later served as dean of the University of Iowa College of Law.

When Justice James F Byrnes resigned from the Supreme Court, Roosevelt nominated Rutledge to take his place.

Wiley Rutledge's jurisprudence placed a strong emphasis on the protection of civil liberties.

Wiley Rutledge sided with Jehovah's Witnesses seeking to invoke the First Amendment in cases such as West Virginia State Board of Education v Barnette and Murdock v Pennsylvania ; his majority opinion in Thomas v Collins endorsed a broad interpretation of the Free Speech Clause.

In other cases, Wiley Rutledge fervently supported broad due process rights in criminal cases, and he opposed discrimination against women, racial minorities, and the poor.

Wiley Rutledge was among the most liberal justices ever to serve on the Supreme Court.

Wiley Rutledge favored a flexible and pragmatic approach to the law that prioritized the rights of individuals.

Wiley Rutledge died in 1949, having suffered a massive stroke, after six years' service on the Supreme Court.

Wiley Rutledge attended seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, and then moved with his wife to pastor a church in Cloverport.

Wiley Rutledge studied Latin and Greek, successfully maintaining high grades throughout.

At Maryville, Wiley Rutledge participated vigorously in debate; he argued in support of Woodrow Wilson and against the progressivism of Theodore Roosevelt.

Wiley Rutledge played football, developed a reputation as a practical jokester, and began a romantic relationship with Person, who was five years his senior.

Lonely and struggling in his classwork, Wiley Rutledge had a difficult time in Wisconsin, and he later characterized it as being one of the "hardest" and most "painful" periods of his life.

The ailing Wiley Rutledge removed himself to a sanatorium and gradually began to recover from his disease; while there, he married Person.

In 1920, Wiley Rutledge enrolled at the University of Colorado Law School in Boulder; he continued teaching high school as he again pursued the study of law.

Wiley Rutledge later stated that he "owe[d] more professionally to Governor Hadley than to any other person"; Hadley's support for Roscoe Pound's progressive theory of sociological jurisprudence influenced Wiley Rutledge's view of the law.

Wiley Rutledge graduated with a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1922.

Wiley Rutledge passed the bar examination in June 1922 and took a job with the law firm of Goss, Kimbrough, and Hutchison in Boulder.

Wiley Rutledge taught a wide variety of classes, and his colleagues commented that he was experiencing "very considerable success".

Wiley Rutledge spent nine years there, continuing to teach classes pertaining to many aspects of the law.

From 1930 to 1935, Wiley Rutledge served as dean of the law school; he then spent four years as dean of the University of Iowa College of Law.

Wiley Rutledge frequently weighed in on questions of public importance, supporting academic freedom and free speech at Washington University and opposing the Supreme Court's approach to child labor laws.

Wiley Rutledge came down firmly on Roosevelt's side: he denounced the Court's rulings striking down portions of the New Deal and voiced support for the President's unsuccessful "court-packing plan", which attempted to make the Court more amenable to Roosevelt's agenda by increasing the number of justices.

In Wiley Rutledge's view, the justices of his era had "imposed their own political philosophy" rather than the law in their decisions; as such, he felt that expanding the Court was a regrettable but necessary way for Congress to bring it back into line.

Wiley Rutledge appeared before a Senate subcommittee; its members promptly endorsed the nomination.

Wiley Rutledge's jurisprudence emphasized the spirit of the law over the letter of the law; he rejected the use of technicalities to penalize individuals or to circumvent a law's underlying purpose.

Wiley Rutledge had no desire to be nominated to the Supreme Court, but his friends nonetheless wrote to Roosevelt and Biddle on his behalf.

Additionally, the fact that Wiley Rutledge was a Westerner weighed in his favor.

Roosevelt formally nominated Wiley Rutledge, who was then forty-eight years old, to the Supreme Court on January 11,1943.

Ferguson later spoke with Wiley Rutledge and indicated that his concerns had been resolved, but Wheeler, who had strongly opposed Roosevelt's efforts to enlarge the Court, said that he would vote against the nomination when it came before the full Senate.

Wiley Rutledge served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court from 1943 until his death in 1949.

Wiley Rutledge penned a total of sixty-five majority opinions, forty-five concurrences, and sixty-one dissents.

Wiley Rutledge found it challenging to write opinions, and his writing style has been criticized as unnecessarily prolix and difficult to read.

Wiley Rutledge was one of the most liberal justices in the history of the Court.

Wiley Rutledge voted more often than any of his colleagues in favor of individuals who brought suit against the government, and he forcefully advocated for equal protection, access to the courts, due process, and the rights protected by the First Amendment.

Wiley Rutledge's appointment had an immediate effect on a Court that was decidedly split on questions involving the freedoms protected by the First Amendment.

Wiley Rutledge rejected Texas's arguments that the law was subject only to rational-basis review because labor organizing was akin to the sort of ordinary business activity that states could freely regulate.

In dissent, Wiley Rutledge favored an even stricter understanding of the Establishment Clause than Black, maintaining that its purpose "was to create a complete and permanent separation of the spheres of religious activity and civil authority by comprehensively forbidding every form of public aid or support for religion".

Wiley Rutledge supported an expansive definition of due process and construed ambiguous statutes in favor of defendants, particularly in cases involving capital punishment.

Wiley Rutledge joined the opinion of Justice Harold H Burton, who maintained that "death by installments" was a form of cruel and unusual punishment that violated the Due Process Clause.

Wiley Rutledge maintained that the provisions of the Bill of Rights protected all criminal defendants, regardless of whether they were being tried in state or federal court.

Wiley Rutledge joined a dissent by Murphy and penned a separate opinion of his own, in which he argued that, without the exclusionary rule, the Fourth Amendment prohibition of unlawful searches and seizures "was a dead letter".

Wiley Rutledge denounced the majority opinion as an abdication of the Court's responsibility to apply the rule of law to all, even to the military.

Wiley Rutledge wrote privately that he felt the case would "outrank Dred Scott in the annals of the Court".

Wiley Rutledge wrote privately that he had experienced "more anguish over this case" than almost any other, but he eventually voted to sustain Hirabayashi's conviction.

Wiley Rutledge joined Black's opinion immediately and unreservedly, silently taking part in what Ferren called "one of the saddest episodes in the Court's history".

Ferren suggests two possibilities: either Wiley Rutledge "abandon[ed] principle out of loyalty to his president" or he "act[ed] instead with a kind of courage" by reluctantly reaching an unpalatable conclusion that he felt the Constitution required.

In Ferren's view, "[t]he irony for Wiley Rutledge, when viewed in hindsight, is that he participated in a ruling of the sort that he would have berated, in other contexts, as another 'Dred Scott decision".

In cases involving equal protection, Wiley Rutledge opposed discrimination against women, the poor, and racial minorities.

Wiley Rutledge's focus on the law's rationality mirrored the strategy pursued by future Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in her efforts as an ACLU attorney to challenge laws that discriminated on the basis of gender.

Dissenting in Foster v Illinois, Rutledge voted to reverse the convictions of defendants who had not been informed of their right to counsel.

Wiley Rutledge invoked the Due Process Clause but maintained that equal protection had been violated, writing that poorer defendants, lacking an understanding of their rights, would receive "only the shadow of constitutional protections".

Wiley Rutledge dissented, arguing that Oklahoma's law school should be shut down in its entirety if the state refused to admit Sipuel.

Cases involving voting rights were the only ones in which Wiley Rutledge rejected attempts to invoke the Equal Protection Clause.

In MacDougall v Green, Rutledge similarly voted to defer to the states on questions involving election procedures.

Again parting ways with Black, Douglas, and Murphy but refusing to join the majority's analysis, Wiley Rutledge declined to grant the Progressive Party relief, maintaining that there was not enough time before the election for the state to print new ballots.

In both cases, Wiley Rutledge's vote was based on his concern that any possible remedy for the constitutional problem would be unfair as well.

Wiley Rutledge decried the district court's decision to hold the union in both civil and criminal contempt, writing that "the idea that a criminal prosecution and a civil suit for damages or equitable relief could be hashed together in a single criminal-civil hodgepodge would be shocking to every American lawyer and to most citizens".

In cases involving the Constitution's Commerce Clause, Wiley Rutledge favored a pragmatic approach that endeavored to balance the interests of states and the federal government.

Wiley Rutledge was universally regarded as a pleasant and friendly man who genuinely cared about everyone with whom he interacted.