1.

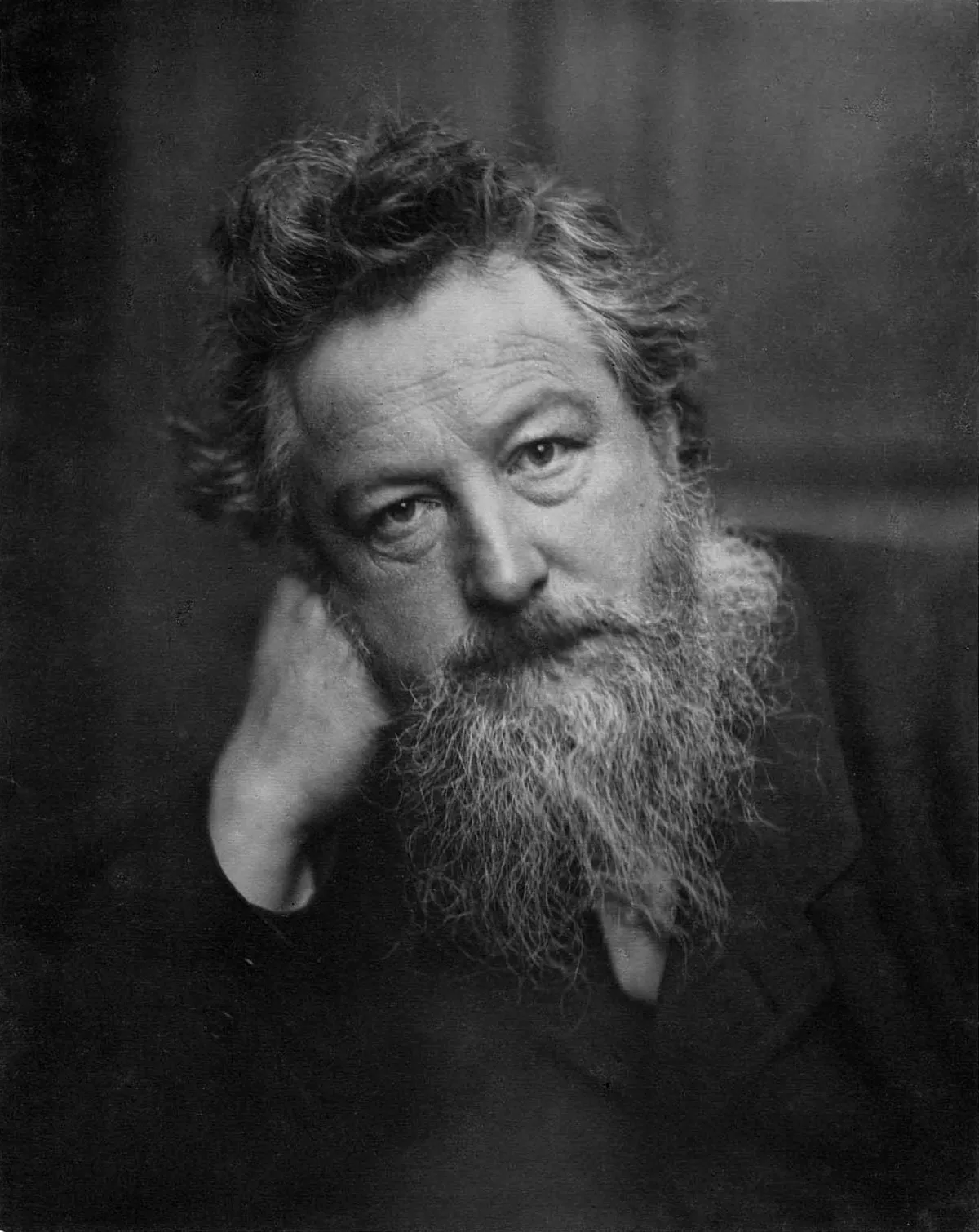

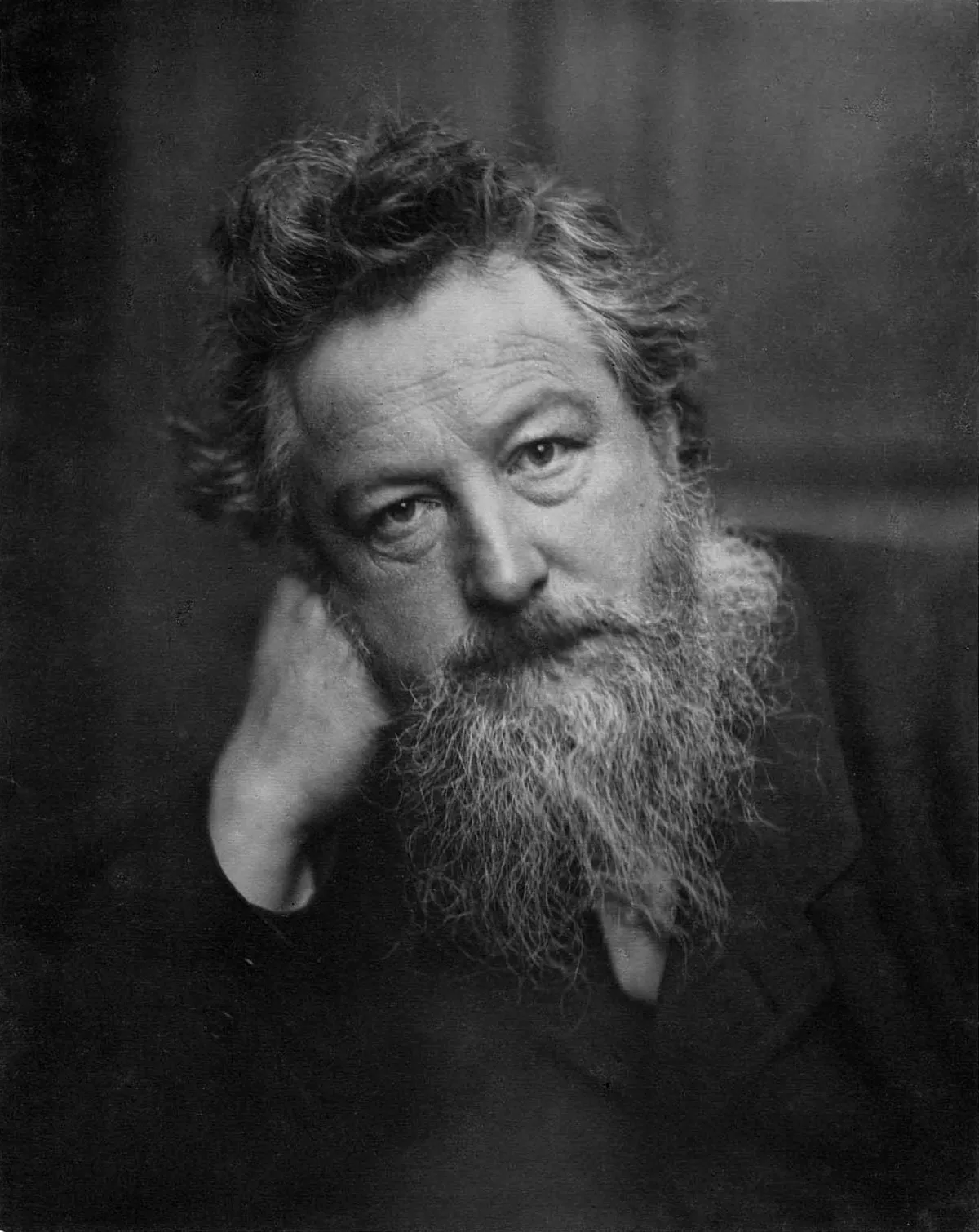

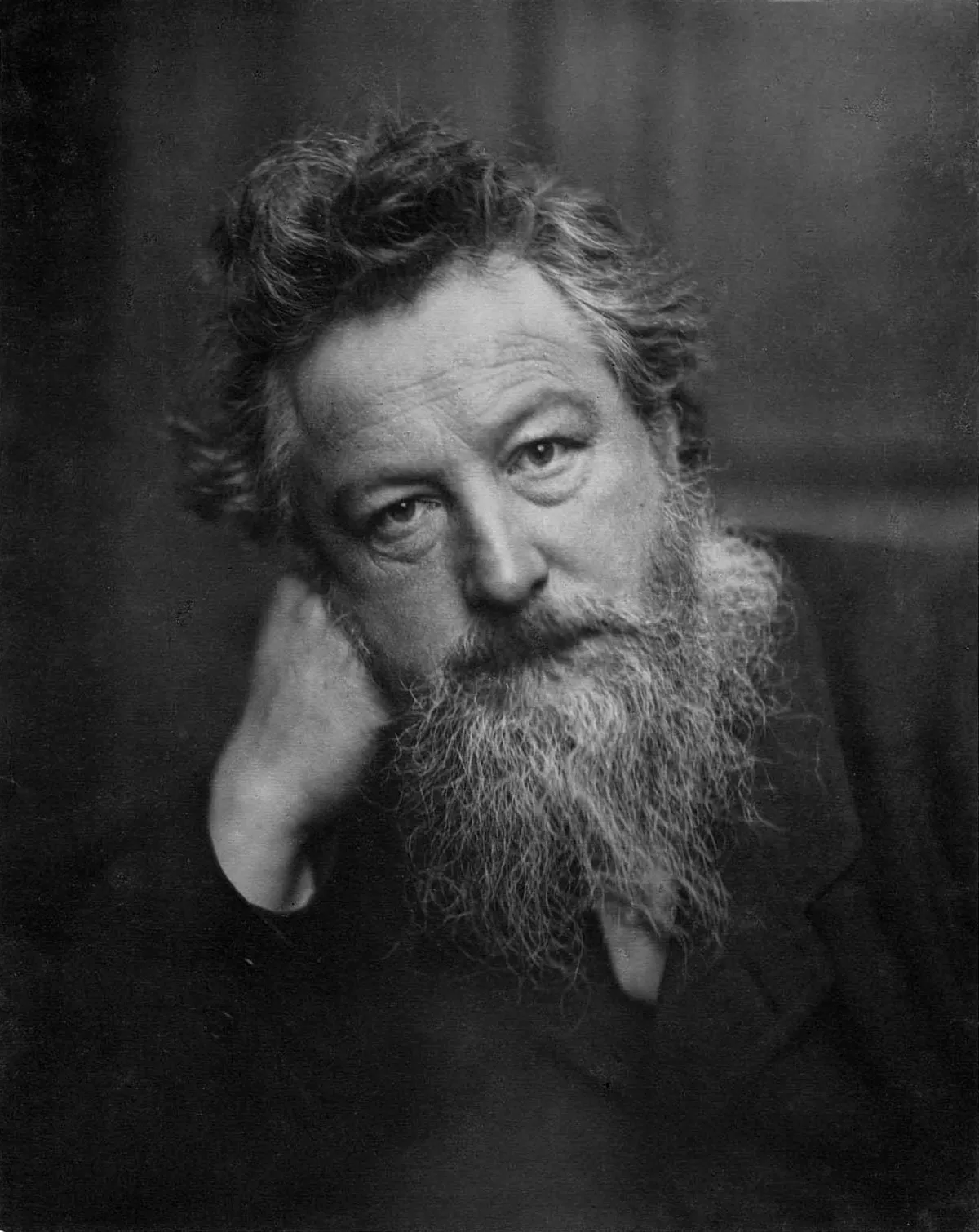

1. William Morris was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement.

1.

1. William Morris was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement.

William Morris was a major contributor to the revival of traditional British textile arts and methods of production.

William Morris came under the strong influence of medievalism while studying classics at Oxford University, where he joined the Birmingham Set.

Webb and William Morris designed Red House in Kent where William Morris lived from 1859 to 1865, before moving to Bloomsbury, central London.

The firm profoundly influenced interior decoration throughout the Victorian period, with William Morris designing tapestries, wallpaper, fabrics, furniture, and stained glass windows.

From 1871, William Morris rented the rural retreat of Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire, while retaining a main home in London.

William Morris was greatly influenced by visits to Iceland with Eirikur Magnusson, and he produced a series of English-language translations of Icelandic Sagas.

William Morris achieved success with the publication of his epic poems and novels, namely The Earthly Paradise, A Dream of John Ball, the Utopian News from Nowhere, and the fantasy romance The Well at the World's End.

William Morris founded the Socialist League in 1884 after an involvement in the Social Democratic Federation, but he broke with that organisation in 1890.

William Morris is recognised as one of the most significant cultural figures of Victorian Britain.

William Morris was best known in his lifetime as a poet, although he posthumously became better known for his designs.

The William Morris Society founded in 1955 is devoted to his legacy, while multiple biographies and studies of his work have been published.

William Morris was born at Elm House in Walthamstow, Essex, on 24 March 1834.

William Morris's mother was Emma Morris, who descended from a wealthy bourgeois family from Worcester.

William Morris was the third of his parents' surviving children; their first child, Charles, had been born in 1827 but died four days later.

The Morris family were followers of the evangelical Protestant form of Christianity, and William was baptised four months after his birth at St Mary's Church, Walthamstow.

Aged 6, William Morris moved with his family to the Georgian Italianate mansion at Woodford Hall, Woodford, Essex, which was surrounded by 50 acres of land adjacent to Epping Forest.

William Morris took an interest in fishing with his brothers as well as gardening in the Hall's grounds, and spent much time exploring the Forest, where he was fascinated both by the Iron Age earthworks at Loughton Camp and Ambresbury Banks and by the Early Modern Hunting Lodge at Chingford.

William Morris took rides through the Essex countryside on his pony, and visited the various churches and cathedrals throughout the country, marveling at their architecture.

William Morris's father took him on visits outside of the county, for instance to Canterbury Cathedral, the Chiswick Horticultural Gardens, and to the Isle of Wight, where he adored Blackgang Chine.

In February 1848 William Morris began his studies at Marlborough College in Marlborough, Wiltshire, where he gained a reputation as an eccentric nicknamed "Crab".

William Morris despised his time there, being bullied, bored, and homesick.

William Morris did use the opportunity to visit many of the prehistoric sites of Wiltshire, such as Avebury and Silbury Hill, which fascinated him.

The school was Anglican in faith and in March 1849 William Morris was confirmed by the Bishop of Salisbury in the college chapel, developing an enthusiastic attraction towards the Anglo-Catholic movement and its Romanticist aesthetic.

At Christmas 1851, Morris was removed from the school and returned to Water House, where he was privately tutored by the Reverend Frederick B Guy, Assistant Master at the nearby Forest School.

In June 1852 William Morris entered Exeter College at Oxford University, although, since the college was full, he went into residence only in January 1853.

William Morris disliked the college and was bored by the manner in which they taught him Classics.

At the college, William Morris met fellow first-year undergraduate Edward Burne-Jones, who became his lifelong friend and collaborator.

William Morris was the most affluent member of the Set, and was generous with his wealth toward the others.

William Morris was heavily influenced by the writings of the art critic John Ruskin, being particularly inspired by his chapter "On the Nature of Gothic Architecture" in the second volume of The Stones of Venice; he later described it as "one of the very few necessary and inevitable utterances of the century".

William Morris adopted Ruskin's philosophy of rejecting the tawdry industrial manufacture of decorative arts and architecture in favour of a return to hand-craftsmanship, raising artisans to the status of artists, creating art that should be affordable and hand-made, with no hierarchy of artistic mediums.

However, as time went on William Morris became increasingly critical of Anglican doctrine and the idea faded.

In summer 1854, William Morris travelled to Belgium to look at medieval paintings, and in July 1855 went with Burne-Jones and Fulford across northern France, visiting medieval churches and cathedrals.

William Morris's apprenticeship focused on architectural drawing, and there he was placed under the supervision of the young architect Philip Webb, who became a close friend.

William Morris soon relocated to Street's London office, in August 1856 moving into a flat in Bloomsbury in Central London with Burne-Jones, an area perhaps chosen for its avant-garde associations.

William Morris became increasingly fascinated with the idyllic Medievalist depictions of rural life which appeared in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, and spent large sums of money purchasing such artworks.

Tired of architecture, William Morris abandoned his apprenticeship, with Rossetti persuading him to take up painting instead, which he chose to do in the Pre-Raphaelite style.

William Morris aided Rossetti and Burne-Jones in painting the Arthurian murals at the Oxford Union, although his contributions were widely deemed inferior and unskilled compared to those of the others.

William Morris designed and commissioned furniture for the flat in a medieval style, much of which he painted with Arthurian scenes in a direct rejection of mainstream artistic tastes.

William Morris continued writing poetry and began designing illuminated manuscripts and embroidered hangings.

In October 1857 William Morris met Jane Burden, a woman from a poor working-class background, at a theatre performance.

William Morris desired a new home for himself and his daughters resulting in the construction of the Red House in the Kentish hamlet of Upton near Bexleyheath, ten miles from central London.

The building's design was a co-operative effort, with William Morris focusing on the interiors and the exterior being designed by Webb, for whom the House represented his first commission as an independent architect.

William Morris was slowly abandoning lithography and painting, recognising that his work lacked a sense of movement; none of his paintings are dated later than 1862.

William Morris's designs were produced from 1864 by Jeffrey and Co.

William Morris retained an active interest in various groups, joining the Hogarth Club, the Mediaeval Society, and the Corps of Artist Volunteers, the latter in contrast to his later pacifism.

In January 1861, William Morris and Janey's first daughter was born: named Jane Alice William Morris, she was commonly known as "Jenny".

William Morris was a caring father to his daughters, and years later they both recounted having idyllic childhoods.

William Morris sold Red House, and in autumn 1865 moved with his family to No 26 Queen Square in Bloomsbury, the same building to which the Firm had moved its base of operations earlier in the summer.

At Queen Square, the William Morris family lived in a flat directly above the Firm's shop.

Taylor pulled the Firm's finances into order and spent much time controlling William Morris and ensuring that he worked to schedule.

However, despite its success, the Firm was not turning over a large net profit, and this, coupled with the decreasing value of William Morris's stocks, meant that he had to decrease his spending.

William Morris went on various holidays; in the summer of 1866 he, Webb, and Taylor toured the churches of northern France.

William Morris had continued to devote much time to writing poetry.

From 1865 to 1870, William Morris worked on another epic poem, The Earthly Paradise.

William Morris was keenly interested in Icelandic literature, having befriended the Icelandic theologian Eirikur Magnusson.

William Morris developed a keen interest in creating handwritten illuminated manuscripts, producing 18 such books between 1870 and 1875, the first of which was A Book of Verse, completed as a birthday present for Georgina Burne-Jones.

William Morris deemed calligraphy to be an art form, and taught himself both Roman and italic script, as well as learning how to produce gilded letters.

William Morris adored the building, which was constructed circa 1570, and would spend much time in the local countryside.

William Morris divided his time between London and Kelmscott, however when Rossetti was there he would not spend more than three days at a time at the latter.

William Morris became fed up with his family home in Queen Square, deciding to obtain a new house in London.

Now in complete control of the Firm, William Morris took an increased interest in the process of textile dyeing and entered into a co-operative agreement with Thomas Wardle, a silk dyer who operated the Hencroft Works in Leek, Staffordshire.

The Firm was obtaining increasing numbers of commissions from aristocrats, wealthy industrialists, and provincial entrepreneurs, with William Morris furnishing parts of St James's Palace and the chapel at Eaton Hall.

William Morris continued producing translations of Icelandic tales with Magnusson, including Three Northern Love Stories and Voluspa Saga.

In 1877 William Morris was approached by Oxford University and offered the largely honorary position of Professor of Poetry.

William Morris declined, asserting that he felt unqualified, knowing little about scholarship on the theory of poetry.

William Morris named it Kelmscott House and re-decorated it according to his own taste.

William Morris became politically active in this period, coming to be associated with the radicalist current within British liberalism.

William Morris joined the Eastern Question Association and was appointed the group's treasurer in November 1876.

William Morris eventually became disillusioned with the EQA, describing it as being "full of wretched little personalities".

William Morris nevertheless joined a regrouping of predominantly working-class EQA activists, the National Liberal League, becoming their treasurer in summer 1879; the group remained small and politically ineffective, with Morris resigning as treasurer in late 1881, shortly before the group's collapse.

William Morris was particularly angered that Gladstone's government did not reverse the Disraeli regime's occupation of the Transvaal, introduced the Coercion Bill, and oversaw the Bombardment of Alexandria.

William Morris later related that while he had once believed that "one might further real Socialistic progress by doing what one could on the lines of ordinary middle-class Radicalism", following Gladstone's election he came to realise "that Radicalism is on the wrong line, so to say, and will never develope [sic] into anything more than Radicalism: in fact that it is made for and by the middle classes and will always be under the control of rich capitalists".

In 1876, Morris visited the Church of St John the Baptist, Burford, where he was appalled at the restoration conducted by his old mentor, G E Street.

William Morris recognised that these programs of architectural restoration led to the destruction or major alteration of genuinely old features in order to replace them with "sham old" features, something which appalled him.

William Morris was particularly strong in denouncing the ongoing restoration of Tewkesbury Abbey and was vociferous in denouncing the architects responsible, something that deeply upset Street.

William Morris had initiated a system of profit sharing among the Firm's upper clerks, however this did not include the majority of workers, who were instead employed on a piecework basis.

William Morris was aware that, in retaining the division between employer and employed, the company failed to live up to his own egalitarian ideals, but he defended this, asserting that it was impossible to run a socialist company within a competitive capitalist economy.

William Morris last saw him in 1881, and he died in April the following year.

William Morris described his mixed feelings toward his deceased friend by stating that he had "some of the very greatest qualities of genius, most of them indeed; what a great man he would have been but for the arrogant misanthropy which marred his work, and killed him before his time".

In January 1881, William Morris was involved in the establishment of the Radical Union, an amalgam of radical working-class groups which hoped to rival the Liberals, and became a member of its executive committee.

Britain's first socialist party, the Democratic Federation, had been founded in 1881 by Henry Hyndman, an adherent of the socio-political ideology of Marxism, with William Morris joining the DF in January 1883.

William Morris began to read voraciously on the subject of socialism, including Henry George's Progress and Poverty, Alfred Russel Wallace's Land Nationalisation, and Karl Marx's Das Kapital, although admitted that Marx's economic analysis of capitalism gave him "agonies of confusion on the brain".

In May 1883, William Morris was appointed to the DF's executive committee, and was elected to the position of treasurer.

William Morris aided the DF using his artistic and literary talents; he designed the group's membership card, and helped author their manifesto, Socialism Made Plain, in which they demanded improved housing for workers, free compulsory education for all children, free school meals, an eight-hour working day, the abolition of national debt, nationalisation of land, banks, and railways, and the organisation of agriculture and industry under state control and co-operative principles.

William Morris regularly contributed articles to the newspaper, in doing so befriending another contributor, George Bernard Shaw.

In December 1884, William Morris founded the Socialist League with other SDF defectors.

William Morris composed the SL's manifesto with Bax, describing their position as that of "Revolutionary International Socialism", advocating proletarian internationalism and world revolution while rejecting the concept of socialism in one country.

William Morris remained in contact with other sectors of London's leftist community, being a regular at the socialist International Club in Shoreditch, East London, however he avoided the recently created Fabian Society, deeming it too middle-class.

William Morris visited Dublin, there offering his support for Irish nationalism, and formed a branch of the League at his Hammersmith house.

William Morris was passionate in denouncing the "bullying and hectoring" that he felt socialists faced from the police, and on one occasion was arrested himself after fighting back against a police officer; a magistrate dismissed the charges.

The Black Monday riots of February 1886 led to increased political repression against left-wing agitators, and in July William Morris was again arrested and fined for public obstruction while preaching socialism on the streets.

From January to October 1890, William Morris serialised his novel News from Nowhere in Commonweal, resulting in improved circulation for the paper.

William Morris had continued with his translation work; in April 1887, Reeves and Turner published the first volume of William Morris's translation of Homer's Odyssey, with the second following in November.

In June 1889, William Morris travelled to Paris as the League's delegate to the International Socialist Working Men's Congress, where his international standing was recognised by his being chosen as English spokesman by the Congress committee.

The Second International emerged from the Congress, although William Morris was distraught at its chaotic and disorganised proceedings.

William Morris similarly did not offer initial support for the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, but changed his opinion after the success of their first exhibit, held in Regent Street in October 1888.

In 1893 the Hammersmith Socialist Society co-founded the Joint Committee of Socialist Bodies with representatives of the SDF and Fabian Society; William Morris helped draw up its "Manifesto of English Socialists".

William Morris offered support for leftist activists on trial, including a number of militant anarchists whose violent tactics he nevertheless denounced.

William Morris embarked on a translation of the Anglo-Saxon tale Beowulf; because he could not fully understand Old English, his poetic translation was based largely on that already produced by Alfred John Wyatt.

In January 1891, William Morris founded the Kelmscott Press, a private press which would go on to publish the celebrated Kelmscott Chaucer.

Obituaries appearing throughout the national press reflected that at the time, William Morris was widely recognised primarily as a poet.

William Morris has a loud voice and a nervous restless manner and a perfectly unaffected and businesslike address.

William Morris's talk indeed is wonderfully to the point and remarkable for clear good sense.

Politically, William Morris was a staunch revolutionary socialist and anti-imperialist, and although raised a Christian he came to be an atheist.

William Morris came to reject state socialism and large centralised control, instead emphasising localised administration within a socialist society.

Later political activist Derek Wall suggested that William Morris could be classified as an ecosocialist.

William Morris believed that it led to little more than a "yearning nostalgia or a sweet complaint" and that Morris became "a realist and a revolutionary" only when he adopted socialism in 1882.

Mackail was of the opinion that William Morris had an "innate Socialism" which had "penetrated and dominated all he did" throughout his life.

William Morris was of a nervous disposition, and throughout his life relied on networks of male friends to aid him in dealing with this.

William Morris's friends nicknamed him "Topsy" after a character in Uncle Tom's Cabin.

William Morris had a wild temper and when sufficiently enraged could suffer seizures and blackouts.

Biographer Fiona MacCarthy suggests that William Morris might have suffered from a form of Tourette's syndrome.

Besides being an artist William Morris was a prolific writer of poetry, fiction, essays, and translations of ancient and medieval texts.

William Morris began publishing poetry and short stories in 1856 through The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine which he founded with his friends and financed while at university.

William Morris met Eirikur Magnusson in 1868, and began to learn the Icelandic language from him.

William Morris published translations of The Saga of Gunnlaug Worm-Tongue and Grettis Saga in 1869, and the Story of the Volsungs and Niblungs in 1870.

The young Tolkien attempted a retelling of the story of Kullervo from the Kalevala in the style of The House of the Wolfings; Tolkien considered much of his literary work to have been inspired by an early reading of William Morris, even suggesting that he was unable to better William Morris's work; the names of characters such as "Gandolf" and the horse Silverfax appear in The Well at the World's End.

William Morris emphasised the idea that the design and production of an item should not be divorced from one another, and that where possible those creating items should be designer-craftsmen, thereby both designing and manufacturing their goods.

William Morris observed the natural world first hand to gain a basis for his designs, and insisted on learning the techniques of production prior to producing a design.

William Morris was fond of hand-knotted Persian carpet and advised the South Kensington Museum in the acquisition of fine Kerman carpets.

William Morris taught himself embroidery, working with wool on a frame custom-built from an old example.

William Morris took up the practical art of dyeing as a necessary adjunct of his manufacturing business.

William Morris spent much of his time at Staffordshire dye works mastering the processes of that art and making experiments in the revival of old or discovery of new methods.

William Morris's work inspired many small private presses in the following century.

William Morris's efforts were constantly directed towards giving the world at least one book that exceeded anything that had ever appeared.

William Morris designed his type after the best examples of early printers, what he called his "golden type" which he copied after Jenson, Parautz, Coburger and others.

William Morris was a major contributor to the revival of traditional British textile arts and methods of production.

William Morris's ethos of production was an influence on the Bauhaus movement.

Aymer Vallance was commissioned to produce the first biography of William Morris, published in 1897, after William Morris's death, per the latter's wishes.

William Morris has exerted a powerful influence on thinking about art and design over the past century.

William Morris has been the constant niggle in the conscience.

William Morris burned with guilt at the fact that his "good fortune only" allowed him to live in beautiful surroundings and to pursue the work he adored.

In 2025, the William Morris Gallery opened the exhibition Morris Mania, examining how Morris' designs became globally recognised.

The William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow, England, is a public museum devoted to Morris's life, work and influence.

The William Morris Society is based at Morris's final London home, Kelmscott House, Hammersmith, and is an international members society, museum and venue for lectures and other Morris-related events.

The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, acquired the collection of William Morris materials amassed by Sanford and Helen Berger in 1999.

William Morris's Beowulf was one of the first translations of the Old English poem into modern English.