1.

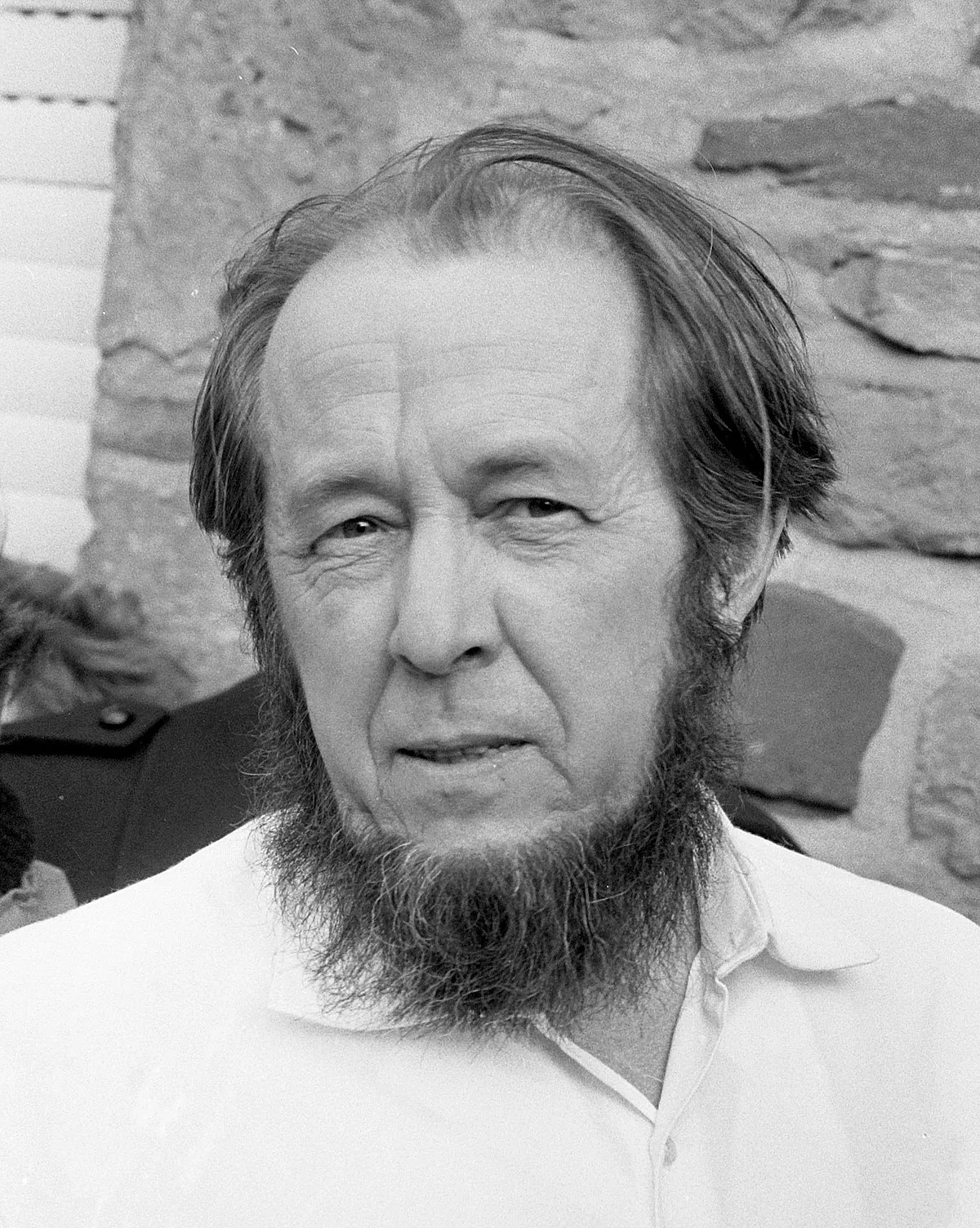

1. Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was a Soviet and Russian author and dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag prison system.

1.

1. Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was a Soviet and Russian author and dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag prison system.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature "for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature".

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn pursued writing novels about repression in the Soviet Union and his experiences.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn initially moved to Switzerland and then moved to Vermont in the United States with his family in 1976 and continued to write there.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia four years later and remained there until his death in 2008.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was raised by his widowed mother and his aunt in lowly circumstances.

Later, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn recalled that his mother had fought for survival and that they had to keep his father's background in the old Imperial Army a secret.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's educated mother encouraged his literary and scientific learnings and raised him in the Russian Orthodox faith; she died in 1944 having never remarried.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Order of the Red Star on 8 July 1944 for sound-ranging two German artillery batteries and adjusting counterbattery fire onto them, resulting in their destruction.

In February 1945, while serving in East Prussia, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was arrested by SMERSH for writing derogatory comments in private letters to a friend, Nikolai Vitkevich, about the conduct of the war by Joseph Stalin, whom he called "Hozyain", and "Balabos".

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had talks with the same friend about the need for a new organization to replace the Soviet regime.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was accused of anti-Soviet propaganda under Article 58, paragraph 10 of the Soviet criminal code, and of "founding a hostile organization" under paragraph 11.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was taken to the Lubyanka prison in Moscow, where he was interrogated.

In 1950, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was sent to a "Special Camp" for political prisoners.

One of his fellow political prisoners, Ion Moraru, remembers that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn spent some of his time at Ekibastuz writing.

In March 1953, after his sentence ended, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was sent to internal exile for life at Birlik, a village in Baidibek District of South Kazakhstan.

In 1954, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was permitted to be treated in a hospital in Tashkent, where his tumor went into remission.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn repented for some of his actions as a Red Army captain, and in prison compared himself to the perpetrators of the Gulag.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's transformation is described at some length in the fourth part of The Gulag Archipelago.

On 7 April 1940, while at the university, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn married Natalia Alekseevna Reshetovskaya.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn contended that it was, rather, a collection of "camp folklore", containing "raw material" which her husband was planning to use in his future productions.

In 1973, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn married his second wife, Natalia Dmitrievna Svetlova, a mathematician who had a son, Dmitri Turin, from a brief prior marriage.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Svetlova was born on 1939 and had three sons: Yermolai, Ignat, and Stepan.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn made an unsuccessful attempt, with the help of Tvardovsky, to have his novel Cancer Ward legally published in the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn continued to secretly and feverishly work on the most well-known of his writings, The Gulag Archipelago.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had befriended Arnold Susi, a lawyer and former Minister of Education of Estonia in a Lubyanka Building prison cell.

In 1969, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Union of Writers.

In 1973, another manuscript written by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was confiscated by the KGB after his friend Elizaveta Voronyanskaya was questioned non-stop for five days until she revealed its location, according to a statement by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn to Western reporters on September 6,1973.

On 8 August 1971, the KGB allegedly attempted to assassinate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn using an unknown chemical agent with an experimental gel-based delivery method.

On 12 February 1974, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was arrested and deported the next day from the Soviet Union to Frankfurt, West Germany and stripped of his Soviet citizenship.

US military attache William Odom managed to smuggle out a large portion of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's archive, including the author's membership card for the Writers' Union and his Second World War military citations.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn paid tribute to Odom's role in his memoir Invisible Allies.

In West Germany, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn lived in Heinrich Boll's house in Langenbroich.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn then moved to Zurich, Switzerland before Stanford University invited him to stay in the United States to "facilitate your work, and to accommodate you and your family".

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn stayed at the Hoover Tower, part of the Hoover Institution, before moving to Cavendish, Vermont, in 1976.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was given an honorary literary degree from Harvard University in 1978 and on 8 June 1978 he gave a commencement address, condemning, among other things, the press, the lack of spirituality and traditional values, and the anthropocentrism of Western culture.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn received an honorary degree from the College of the Holy Cross in 1984.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn called for Russia to "renounce all mad fantasies of foreign conquest and begin the peaceful long, long long period of recuperation," as he put it in a 1979 BBC interview with Latvian-born BBC journalist Janis Sapiets.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn published eight two-part short stories, a series of contemplative "miniatures" or prose poems, and a literary memoir on his years in the West The Grain Between the Millstones, translated and released as two works by the University of Notre Dame as part of the Kennan Institute's Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Initiative.

Once back in Russia, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn hosted a television talk show program.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn became a supporter of Vladimir Putin, who said he shared Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's critical view towards the Russian Revolution.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn died of heart failure near Moscow on 3 August 2008, at the age of 89.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was buried the same day in the monastery, in a spot he had chosen.

Russian and world leaders paid tribute to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn following his death.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn sought refuge in a dreamy past, where, he believed, a united Slavic state built on Orthodox foundations had provided an ideological alternative to western individualistic liberalism.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn repeatedly denounced Tsar Alexis of Russia and Patriarch Nikon of Moscow for causing the Great Schism of 1666, which Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn said both divided and weakened the Russian Orthodox Church at a time when unity was desperately needed.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn attacked both the Tsar and the Patriarch for using excommunication, Siberian exile, imprisonment, torture, and even burning at the stake against the Old Believers, who rejected the liturgical changes which caused the Schism.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn argued that the Dechristianization of Russian culture, which he considered most responsible for the Bolshevik Revolution, began in 1666, became much worse during the Reign of Tsar Peter the Great, and accelerated into an epidemic during The Enlightenment, the Romantic era, and the Silver Age.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn argued that both Russian Gentiles and Jews should be prepared to treat the atrocities committed by Jewish and Gentile Bolsheviks as though they were the acts of their own family members, before their consciences and before God.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn bears some resemblance to Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who was a fervent Christian and patriot and a rabid anti-Semite.

Award-winning Jewish novelist and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel disagreed and wrote that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was "too intelligent, too honest, too courageous, too great a writer" to be an anti-Semite.

In 2001, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn published a two-volume work on the history of Russian-Jewish relations.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn downplayed the number of victims of an 1882 pogrom despite current evidence, and failed to mention the Beilis affair, a 1911 trial in Kiev where a Jew was accused of ritually murdering Christian children.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was criticized for relying on outdated scholarship, ignoring current western scholarship, and for selectively quoting to strengthen his preconceptions, such as that the Soviet Union often treated Jews better than non-Jewish Russians.

Similarities between Two Hundred Years Together and an anti-Semitic essay titled "Jews in the USSR and in the Future Russia", attributed to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, have led to the inference that he stands behind the anti-Semitic passages.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn himself explained that the essay consists of manuscripts stolen from him by the KGB, and then being published, 40 years before, without his consent.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn viewed the Soviet Union as a police state significantly more oppressive than the Russian Empire's House of Romanov.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn noted that the Tsar's secret police, the Okhrana, was only present in the three largest cities, and not at all in the Imperial Russian Army.

Shortly before his return to Russia, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn delivered a speech in Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Vendee Uprising.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn compared the Vendean rebels with the Russian, Ukrainian, and Cossack peasants who rebelled against the Bolsheviks, saying that both were destroyed mercilessly by revolutionary despotism.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn commented that, while the French Reign of Terror ended with the Thermidorian reaction and the toppling of the Jacobins and the execution of Maximilien Robespierre, its Soviet equivalent continued to accelerate until the Khrushchev thaw of the 1950s.

Therefore, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn argued, moderate and non-colonialist Russian nationalism and the Russian Orthodox Church, once cleansed of Caesaropapism, should not be regarded as a threat to the civilization of the West but rather as its ally.

Winston Lord, a protege of the then United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, called Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, "just about a fascist", and Elisa Kriza alleged that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn held "benevolent views" on Francoist Spain because it was a pro-Christian government, and his Christian worldview operated ideologically.

In "Rebuilding Russia", an essay first published in 1990 in Komsomolskaya Pravda, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn urged the Soviet Union to grant independence to all the non-Slav republics, which he claimed were sapping the Russian nation and he called for the creation of a new Slavic state bringing together Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and parts of Kazakhstan that he considered to be Russified.

In some of his later political writings, such as Rebuilding Russia and Russia in Collapse, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn criticized the oligarchic excesses of the new Russian democracy, while opposing any nostalgia for Soviet Communism.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn defended moderate and self-critical patriotism.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn urged for local self-government similar to what he had seen in New England town meetings and in the cantons of Switzerland.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn expressed concern for the fate of the 25 million ethnic Russians in the "near abroad" of the former Soviet Union.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn refused to accept Russia's highest honor, the Order of St Andrew, in 1998.

In 2008, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn praised Putin, saying Russia was rediscovering what it meant to be Russian.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn praised the Russian president Dmitry Medvedev as a "nice young man" who was capable of taking on the challenges Russia was facing.

Once in the United States, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn sharply criticized the West.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn criticized the Allies for not opening a new front against Nazi Germany in the west earlier in World War II.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn said the Western democracies apparently cared little about how many died in the East, as long as they could end the war quickly and painlessly for themselves in the West.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn added "should someone ask me whether I would indicate the West such as it is today as a model to my country, frankly I would have to answer negatively".

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn critiqued the West for its lack of religiosity, materialism, and a "decline in courage".

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn considered the West to possess a blind sense of cultural superiority, and that this manifested itself as the belief that "vast regions everywhere on our planet should develop and mature to the level of present-day Western systems".

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was a supporter of the Vietnam War and referred to the Paris Peace Accords as 'shortsighted' and a 'hasty capitulation'.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn accused the Western news media of left-wing bias, of violating the privacy of celebrities, and of filling up the "immortal souls" of their readers with celebrity gossip and other "vain talk".

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn said that the West erred in thinking that the whole world should embrace this as model.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn criticized the 2003 invasion of Iraq and accused the United States of the "occupation" of Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was critical of NATO's eastward expansion towards Russia's borders and described the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia as "cruel", a campaign which he said marked a change in Russian attitudes to the West.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn described NATO as "aggressors" who "have kicked aside the UN, opening a new era where might is right".

In 2006, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn accused NATO of trying to bring Russia under its control; he stated that this was visible because of its "ideological support for the 'colour revolutions' and the paradoxical forcing of North Atlantic interests on Central Asia".

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn stated that both famines were caused by systematic armed robbery of the harvests from both Russian and Ukrainian peasants by Bolshevik units, which were under orders from the Politburo to bring back food for the starving urban population centers while refusing for ideological reasons to permit any private sale of food supplies in the cities or to give any payment to the peasants in return for the food that was seized.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn further said that the theory that the Holodomor was a genocide which only victimized the Ukrainian people, was created decades later by believers in an anti-Russian form of extreme Ukrainian nationalism.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn cautioned that the ultranationalists' claims risked being accepted without question in the West due to widespread ignorance and misunderstanding there of both Russian and Ukrainian history.

The documentary was shot in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's home depicting his everyday life and his reflections on Russian history and literature.