1.

1. In 1938, in his early 20s, Andreas Papandreou left Greece for United States to escape the Metaxas' dictatorship and became a prominent academic.

1.

1. In 1938, in his early 20s, Andreas Papandreou left Greece for United States to escape the Metaxas' dictatorship and became a prominent academic.

Andreas Papandreou returned to Greece in 1959 after years of resisting his father's entreaties.

Andreas Papandreou was exiled during the Greek Junta, with many, even his father, blaming him for the fall of democracy.

On his return in 1974, Andreas Papandreou created PASOK, the first organised Greek socialist party.

PASOK won the elections in 1981 and Andreas Papandreou began to implement a transformative social agenda, expanding access to education and healthcare, reinforcing workers' rights, and passing a new family law that elevated the position of women in society and the economy.

Andreas Papandreou secured official recognition of the communist resistance groups in the Greek Resistance making it easier for communist refugees from the Greek Civil War to return.

Andreas Papandreou had transformed Greece's post-junta liberal democracy into a "populist democracy" that continues to resonate with many Greeks.

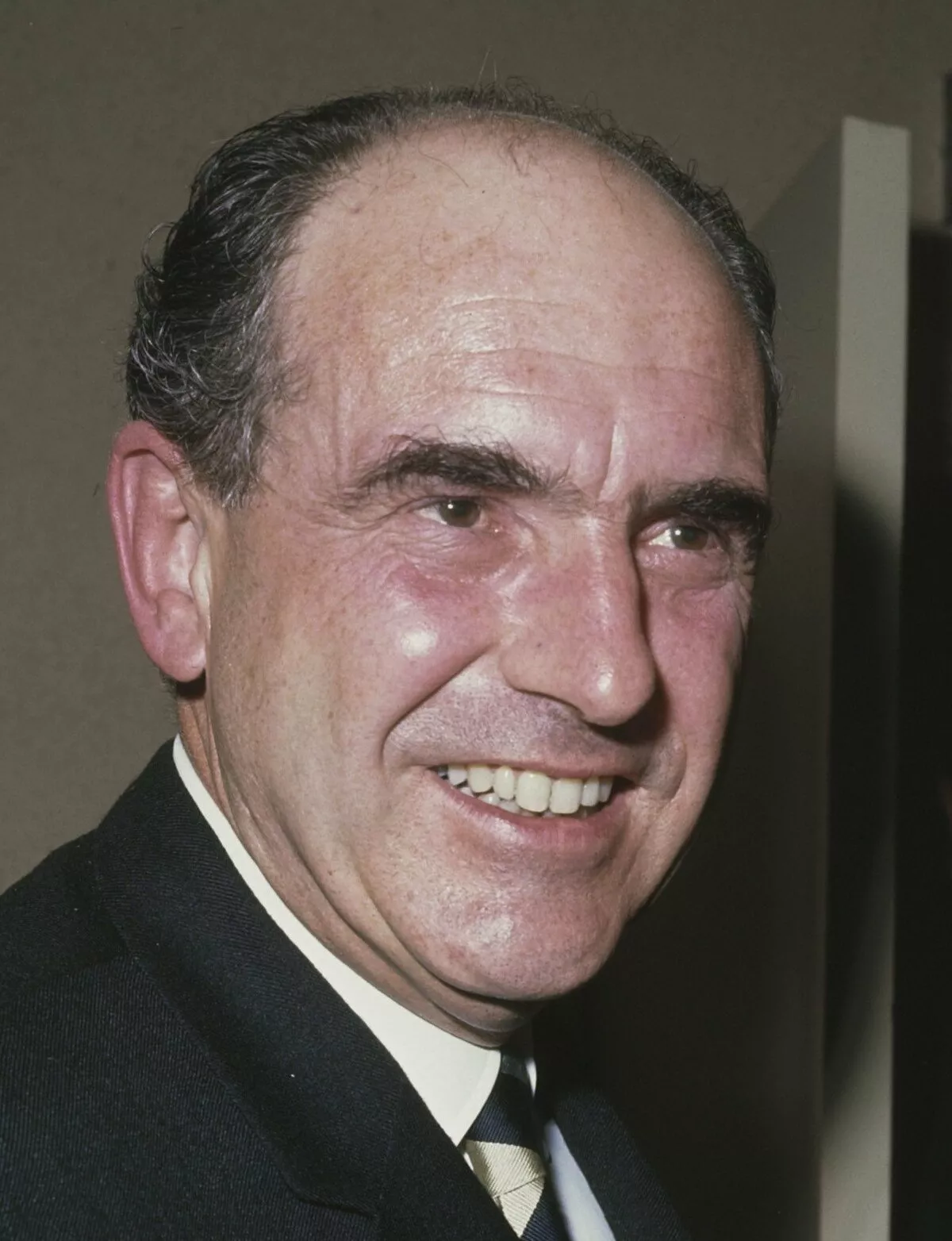

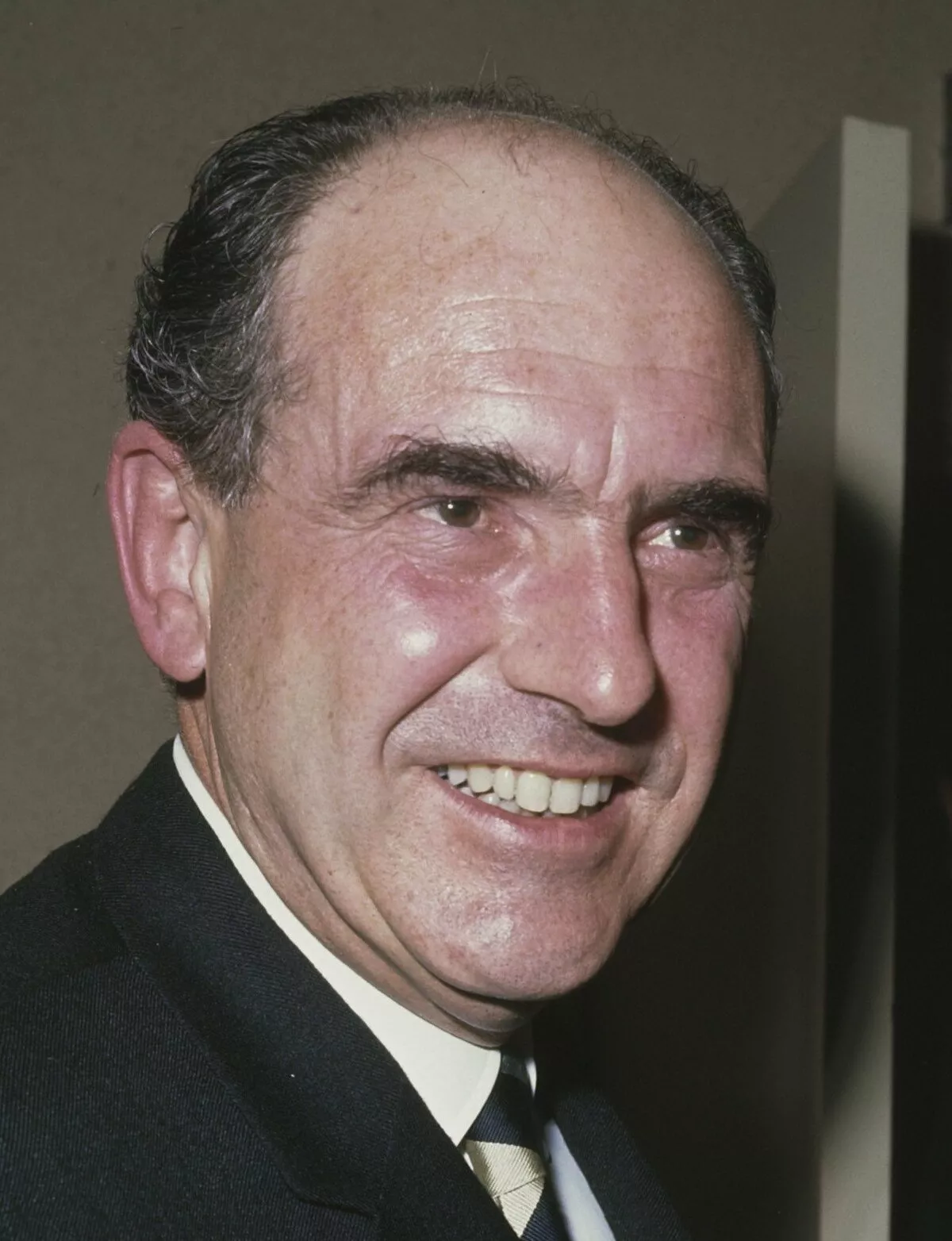

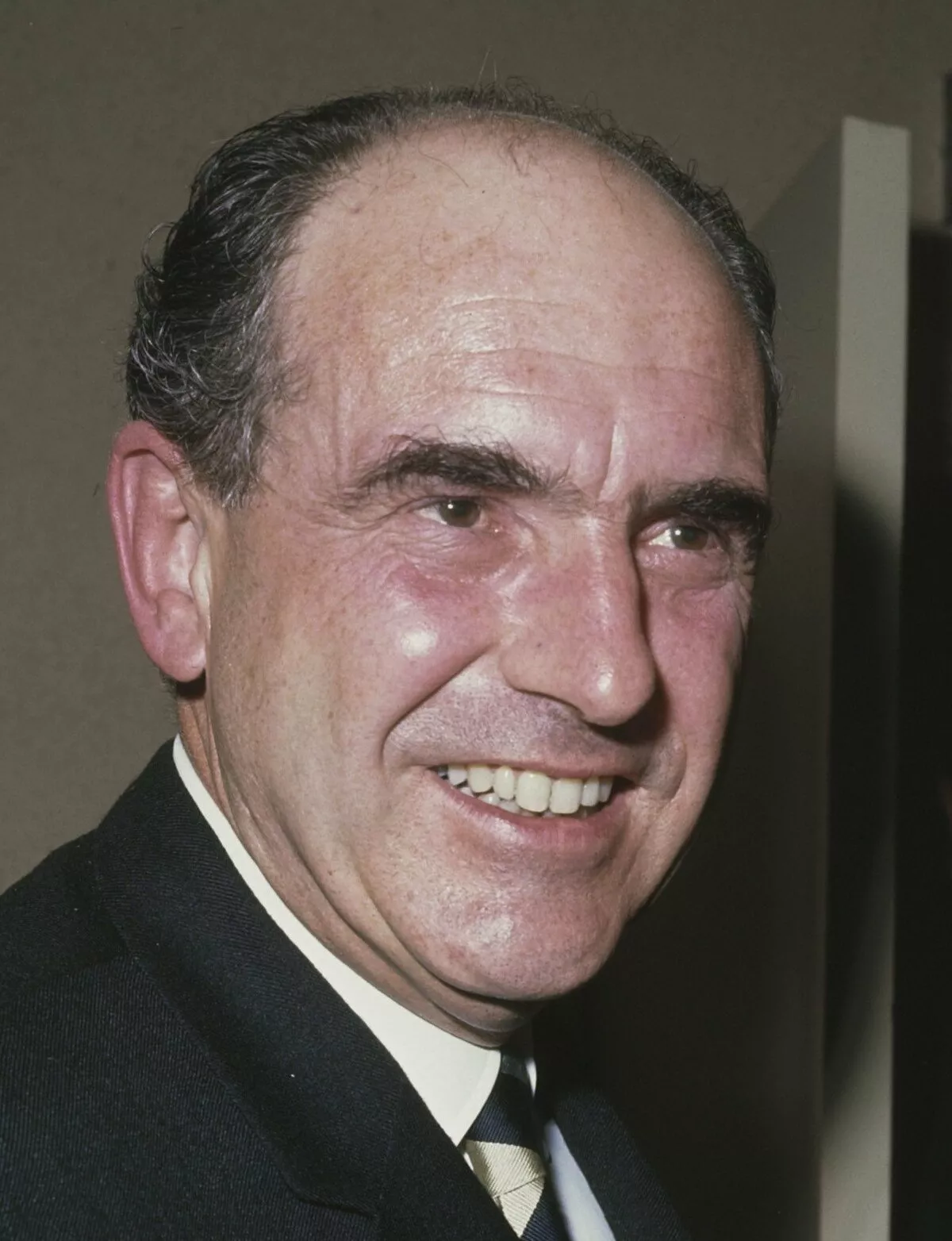

Andreas Papandreou was born on 5 February 1919 on the Greek island of Chios, the son of Zofia Mineyko and Greek liberal politician and future prime minister George Andreas Papandreou.

Andreas Papandreou's maternal grandfather was Polish-Lithuanian-born public figure Zygmunt Mineyko, and his maternal grandmother was Greek.

Andreas Papandreou attended the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens from 1937 until 1938 when, during the dictatorship led by Ioannis Metaxas, he was arrested for purported Trotskyism.

Andreas Papandreou was married to Christina Rasia from 1941 to 1951.

Andreas Papandreou had, with Swedish actress and TV presenter Ragna Nyblom, a daughter out of wedlock, Emilia Nyblom, who was born in 1969 in Sweden.

Andreas Papandreou divorced his second wife Margaret Chant-Andreas Papandreou in 1989, and married Dimitra Liani who was 37 years his junior.

Andreas Papandreou's will shocked the public because he left everything to his 41-year-old third wife and left nothing to his family by the second wife, whom he married for 38 years, and their four children, or the illegitimate Swedish daughter.

In 1943, Papandreou received a PhD degree in economics from Harvard University under the thesis advisor William L Crum.

Immediately after earning his doctorate, Andreas Papandreou joined America's war effort and volunteered to serve in the US Navy; after his basic training in the Great Lakes Naval Training in Illinois, he spent 15 weeks to qualify as a hospital corpsman at the Bethesda Naval Hospital.

Andreas Papandreou returned to Harvard in 1946 and served as a student advisor until 1947, when he received an assistant professorship at the University of Minnesota.

Andreas Papandreou started his career as an academic economist and achieved considerable fame in his field.

Andreas Papandreou received funding from the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Foundation to promote projects aligned to liberal internationalism; initially, American officials hoped that Andreas Papandreou would be a stabilizing force in Greek politics.

Andreas Papandreou considered securing support from the non-communist left-leaning voters the only way to assist his father in becoming Prime Minister.

Andreas Papandreou called for social and economic modernization through a mass-based political party.

Andreas Papandreou became chief economic advisor, renounced his American citizenship, and was elected to the Greek Parliament in the 1964 Greek legislative election.

Andreas Papandreou immediately became assistant Prime Minister and leader of the party's left wing.

The discontent of the members of the Center Union increased as Andreas Papandreou's influence grew to the point that his father started to ignore his own Cabinet on critical political decisions.

Andreas Papandreou's government released all the political prisoners as a first step towards healing wounds from the civil war.

In foreign policy, Andreas Papandreou criticized the presence of American military and intelligence in Greece by describing Greece as a colony of the United States and publicly taking a neutral stand in Cold War.

Andreas Papandreou's rhetoric intensified after his father's visit as Prime Minister to Washington with President Johnson in July 1964 to discuss the Cyprus dispute.

The conservatives feared that Andreas Papandreou was a secret Communist, leading them to another civil war.

Andreas Papandreou increasingly became the target of ultra-rightists who feared that following any new elections, which the nearly 80-year-old Georgios Papandreou would likely win, his son would be the actual focus of power in the party.

In 1965, while the Aspida scandal within the Hellenic Army was being investigated, Georgios Papandreou decided to remove the defense minister and assume the post himself to protect his son from investigations.

Andreas Papandreou temporarily succeeded in bringing 45 members to his side, who later were called 'apostates' by the side supporting Papandreous, and the most prominent was Mitsotakis.

Gust Avrakotos, a Greek-American Central Intelligence Agency case officer assigned to Athens, told the Colonels that the US Government wished for Andreas Papandreou to be allowed to leave the country with his family.

Andreas Papandreou then moved to Sweden with his wife, four children, and mother, where he accepted a post for one year at Stockholm University.

In exile, Andreas Papandreou was a political pariah and excluded from political forces to restore democracy in Greece.

Andreas Papandreou publicly accused the CIA of being responsible for the 1967 coup and became increasingly critical of the US administration, often stating that Greece was a US "colony" and a Cold War "garrison state".

In 1968, Andreas Papandreou formed an anti-dictatorship organization, the Panhellenic Liberation Movement, which sought to 'violently overthrow' the military regime.

George Papandreou, who was under house arrest since the coup and already at an advanced age, died in 1968; Andreas Papandreou was not allowed by the junta regime to attend his father's funeral.

Andreas Papandreou returned to Greece after the fall of the junta in 1974, during metapolitefsi.

The dominant and leading political figure in Greece was Karamanlis with his new political party New Democracy, while Andreas Papandreou continued to have the stigma of past events.

On 6 August 1974, Andreas Papandreou dissolved PAK in Winterthur, Switzerland, without announcing it publicly.

Andreas Papandreou boycotted the promulgation of the constitution and publicly described it as "totalitarian", advocating instead for a "socialist" constitution without explaining what he meant.

Andreas Papandreou's attacks sharpened upon the initiation of talks for the entry of Greece into the EEC, accusing the politicians and the democratic institutions of Greece of "national betrayal".

Andreas Papandreou was able to salvage his political career by doubling down on his polarizing pre-junta-developed ideology by combining it with nationalist elements, which was assisted by three major events.

Andreas Papandreou promised a wide range changes, encapsulated in the PASOK's slogan "Change", which resonated with the Greek people who sought a break from the failed politics of the past.

Andreas Papandreou started to soften his tone without abandoning his initial positions.

Andreas Papandreou frequently stated in his campaigns prior 1981 elections regarding the entry to EEC:.

However, these feelings dissipated by the end of the first administration because Andreas Papandreou made considerable U-turns and followed a more conventional approach, either by choice or by dysfunctional government incapable of undertaking the transformation it had promised.

Andreas Papandreou abandoned his campaign promise of placing Greece's entry to the EEC in a referendum and instead submitted a memorandum to the EEC with a list of demands in March 1982.

In March 1985, Andreas Papandreou stated that Greece would remain in EEC for the foreseeable future because "the cost of leaving would be much higher than the cost of staying"; there was little reaction from PASOK members.

In domestic affairs, Andreas Papandreou's government carried out a series of wealth redistribution policies upon coming into office that immediately increased the availability of entitlement aid to the unemployed and lower wage earners.

Andreas Papandreou did not introduce progressive tax reform to increase the state's revenues to address the increasing budget deficits due to his policies, and instead, he used foreign loans.

In December 1981, at the NATO Defence Planning Committee, Andreas Papandreou demanded, in an acrimonious discussion, NATO guarantees against Turkey, a NATO ally, stating that the true threat for Greece is from the east instead from the north.

When Papandreou publicly stated, "For us, the idea of having foreign bases on our soil is unacceptable since we do not believe in the competition between the two superpowers and Europe's division," his government was quietly renegotiating the stay of the US bases, behind closed doors with US ambassadors Monteagle Stearns and Robert V Keeley who were experienced with the Greek issues.

Andreas Papandreou abolished the function of school inspectors, and the powers of headmasters and headmistresses were diminished, with teachers' committees taking more responsibilities.

Andreas Papandreou's reforms resulted in public schools lagging in academic excellence performance from private schools, which selected qualified teachers and assigned them according to their skills.

Andreas Papandreou made progress in this direction, but unlike Karamanlis, he was pressured to do more since he relied on left-leaning voting blocks.

In December 1982, Andreas Papandreou dropped the security screening requirement, allowing the return of another potential 22,000 returnees; the most notable was Markos Vafiadis at age 77, but excluded any Slav-Macedonian war veterans that participated in the resistance.

Andreas Papandreou introduced a law in 1985 for civil servants dismissed for political reasons to restore their pension.

Once in power, Andreas Papandreou relied on Paraskevas Avgerinos for the establishment of a national healthcare system, which was modeled on Britain's National Health Service.

However, Andreas Papandreou's reforms were not compressive due to budgetary constraints and shortage of specialized doctors, as well as obstruction from professional unions, who refused to give up their private health insurance plans.

Andreas Papandreou then turned to Georgios Gennimatas, a more practical politician familiar with the healthcare reforms.

In 1981, part of Andreas Papandreou's new "Social Contract" was a set of liberalizing laws that redefined the relations between men and women and emphasized the individual as the central unit in society instead of the family.

In 1986, Andreas Papandreou's government passed a law to decriminalize abortion, which was prohibited in all circumstances but practiced on a large scale before then.

Andreas Papandreou's reforms led to a steep decline in the total fertility rate from 2.2 in 1980, which was just above the 2.1 threshold for stabilizing the size of the population, to 1.4 by 1989, which would lead to shrinking the Greek population.

Simultaneously, Andreas Papandreou proposed constitutional reforms to diminish the president's powers, including calling elections or referendums, appointing governments, or dissolving parliament.

Andreas Papandreou argued that Karamanlis, who had heavily influenced the 1974 constitution, should not oversee its reform.

Andreas Papandreou informed Karamanlis of his decision via his deputy, Antonios Livanis.

Mitsotakis accused Andreas Papandreou of violating constitutional protocol, which required a secret ballot, by forcing his deputies to cast their vote with colored ballots, but Mitsotakis was dismissed.

Andreas Papandreou formally submitted the proposals for constitutional amendments by adding to the previous one the removal of a secret ballot for president.

Andreas Papandreou's gamble worked to his benefit because he gained more from far-left voting blocks than the voters lost from the center.

Andreas Papandreou began his second administration with a comfortable majority in the parliament and increased powers based on the 1986 Greek Constitution.

In 1985, Andreas Papandreou's government applied to the EEC for a $1.75 billion loan to deal with the widening foreign trade deficit.

Andreas Papandreou touted the loan as a life savior for the economy of Greece because if they had not, then the International Monetary Fund would have imposed much more strict and severe austerity measures.

However, Andreas Papandreou was shaken by a widespread backlash, with long-running strikes and demonstrations by farmers and major unions in early 1987.

Andreas Papandreou decried the law on the basis that it suppresses civil liberties and the Greek constitution, and he further claimed that no such law is required simply because Greece does not have the social and political conditions for people to cause such violence.

Andreas Papandreou's abolishing anti-terrorism law combined with his opening to 'radical' Arab regimes effectively let terrorists operate in Greece in the 1980s with impunity.

Andreas Papandreou threatened to sink any Turkish ship found in Greek waters.

Andreas Papandreou wanted to hold NATO, and especially the United States, responsible for the Turkish aggressiveness.

Andreas Papandreou ordered the suspension of the operation of the NATO communication base in Nea Makri, and he sent the Greek Foreign Minister, Karolos Papoulias, to Warsaw Pact member, Bulgaria, for consultations with President Zhivkov.

Andreas Papandreou described the meeting as "a great event for the two nations" and "a breakthrough" by Ozal.

Andreas Papandreou sought this agreement to improve his image as a man of peace, while Ozal wanted to improve Turkey's image abroad as his country was under evaluation for full membership of the European Community.

However, only a week after the Davos meeting, Andreas Papandreou was under pressure from Mitsotakis' criticism that Andreas Papandreou focused only on bilateral disputes in Davos and effectively "shelved" the Cyprus dispute.

Andreas Papandreou was forced to denounce the Davos process and famously apologized in Latin from the podium of the Greek parliament.

Andreas Papandreou's escape and the emerging details about state involvement forced Papandreou to reshuffle his cabinet and agree to a parliamentary inquiry.

Koskotas claimed to have delivered $600,000 to Andreas Papandreou hidden in a Pampers box.

Andreas Papandreou denied the allegations, accused the US of attempting to undermine him, and filed a lawsuit against Time, but the scandal drew global attention.

Amid growing political unrest, Andreas Papandreou narrowly survived two no-confidence votes in Parliament, although he expelled dissenting PASOK members, including Antonis Tritsis, a founding member of PASOK.

Koskotas was extradited to Greece in 1991 for the trial, and Andreas Papandreou's trial began in Athens on 11 March 1991.

In 1989, it was revealed that the National Information Service, through the state telecommunications organization OTE, had been bugging over 46,000 phones of allies and enemies in politics, press, business, and law and Andreas Papandreou used the information obtained for PASOK's purposes.

Leaks to pro-PASOK yellow newspapers against Andreas Papandreou's opponents originated from these files.

Andreas Papandreou used the national broadcasting organization as a public relations agency.

The abuse of power continued when Andreas Papandreou changed the electoral law shortly before the June 1989 general elections, a move designed to prevent the absolute majority of a rival political party.

Andreas Papandreou made things worse by ordering his ministers not to cooperate in the handover of power, and official documents and state treaties went missing.

Andreas Papandreou hoped that while PASOK might come second in electoral votes, it could form a government with the support of the other leftist parties, but he was rejected.

Zolotas resigned in April 1990 due to the inability to reverse the continuous deterioration of the Greek economy from Andreas Papandreou's handling of the economy in previous years.

Andreas Papandreou campaigned to bring back the euphoria of the early 1980s.

Lianni, now officially part of the government as Chief of Staff, was the person, along with her staff, that Andreas Papandreou depended upon, alienating many of his senior ministers.

However, Andreas Papandreou was said to favor one of the loyalists without specifying which, but rank and file tended to favor the pro-Europe reformers, reflecting Andreas Papandreou's losing grip on his party.

Andreas Papandreou abandoned his campaign promises and continued the austerity policies of Mitsotakis with minor alterations, expanding the deregulation and liberalization of the economy.

In February 1994, Andreas Papandreou ordered an economic embargo on landlocked North Macedonia due to the ongoing naming dispute regarding the name of the then Republic of Macedonia.

Andreas Papandreou hoped the embargo would have been a bargaining chip, but it backfired since North Macedonia gained considerable sympathy worldwide, damaging Greece's reputation.

Andreas Papandreou announced the "Common Defence Dogma" with the Republic of Cyprus and the intention of expanding the territorial waters to 12 miles, which further disturbed Turkey and increased the chances for another crisis, as it happened at Imia in January 1996, right after the transition of power from Andreas Papandreou to Simitis.

Andreas Papandreou was hospitalized with advanced heart disease and renal failure on 21 November 1995 at Onassio Cardiac Surgery Centre and refused to retire from office.

Andreas Papandreou presented a grand historical narrative of Greece through the prism of binary characterizations, good vs evil, Left vs Right, privileged vs underprivileged, etc.

Andreas Papandreou's populism was used to describe international relations.

The class struggle that Andreas Papandreou campaigned on had little basis in reality, it was instead part of old-fashioned patronage politics.

Andreas Papandreou transformed the localized voter-patron relation, where the patrons were local aristocratic families, into a centralized national machine where the state controlled by PASOK became the source of patronage.

Andreas Papandreou rewarded its loyal supporters with civil service jobs to an unprecedented degree.

One day before the 1989 elections and as the scandals were closing in, Andreas Papandreou's populism reached new heights when, on a balcony, surrounded by a crowd that gathered to watch him, he gave a public command to the Minister of Finance Dimitris Tsovolas to "give it all [to them]" and "Tsovolas, empty the coffers [of the state]," and the crowd chanted these back.

Later on, Andreas Papandreou claimed that he was merely joking, but this event became an infamous moment of the era.

Andreas Papandreou had lifelong experience in political campaigning, which few could match in the metapolitefsi era, and had commanding leadership in setting the narrative of Greece in the greater context.

Lack of experience in Andreas Papandreou's governments led to early failures with costly economic and social consequences.

Andreas Papandreou had unchallenged authority in PASOK to the point of being "authoritarian".

Andreas Papandreou acted as the 'final arbiter,' and he was "ruthless" if he felt threatened.

Andreas Papandreou did not hesitate to silence his intra-party critics with expulsion from PASOK, followed by a character assassination from the pro-PASOK press and even state media.

Andreas Papandreou experimented with various government structures and restarted the government frequently as he holds the record for the most ministerial reshuffles.

Andreas Papandreou found the day-to-day government management less interesting and instead focused on the grant narratives of Greece's democratization process.

Ministers who have worked with Andreas Papandreou have recorded their frustration at Ministerial Councils where Andreas Papandreou would not disagree with anyone.

The result was that Andreas Papandreou's governments were dysfunctional and lacked coordination, with ministers having little or no time until the next reshuffle to implement campaign promises.

Once in power, Andreas Papandreou did not oppose the integration of Greece into the European Union despite his fierce rhetoric against it in the 1970s.

Andreas Papandreou began to implement a political agenda to restructure the Greek economy and improve living standards by increasing access of lower-income and rural populations to state services such as education and healthcare.

Andreas Papandreou implemented a mixture of protectionist measures and extensive state-guaranteed lending.

Andreas Papandreou, to avoid the economic collapse, accepted another loan from EEC in 1985 and was forced to implement austerity to improve the state of the Greek economy.

Andreas Papandreou [Andreas Papandreou] wanted to build a state with better salaries and services.

The austerity measures needed in the Greek economy were implemented in the early 1990s by Mitsotakis, which Andreas Papandreou continued with minor variations after his return in 1993.

Andreas Papandreou continued Karamanlis's opening to Arab countries as part of diversifying diplomatic partners to secure trade deals and investments from petro-dollars countries.

Andreas Papandreou supported the Palestinian liberation cause and advocated the two-state solution while at the same time condemned Israeli policies in the occupied territories.

Andreas Papandreou was co-creator in 1982 of, and subsequently an active participant in, a movement promoted by the Parliamentarians for Global Action, the Initiative of the Six, which included, besides the Greek PM, Mexico's president Miguel de la Madrid, Argentina's president Raul Alfonsin, Sweden's prime minister Olof Palme, Tanzania's president Julius Nyerere and India's prime minister Indira Gandhi.

Andreas Papandreou was highly charismatic, an excellent orator, and skillful in manipulating impressions and achieving his political goals.

Andreas Papandreou used a form of doublespeak, absent in the Greek political language at the time, where the meanings of terms could change depending on the situation.

Andreas Papandreou was a realist on core political issues but a leftist ideologue on peripheral matters.

Andreas Papandreou shifted political power in domestic issues from the conservatives, who dominated Greek politics for decades, to a more populist and centre-left locus.

Andreas Papandreou's mishandling of the Greek economy's reconstruction became a central problem for future governments.

Andreas Papandreou's populism remained popular in a significant fraction of Greek society, despite the deterioration of the economy and the various corruption scandals.