1.

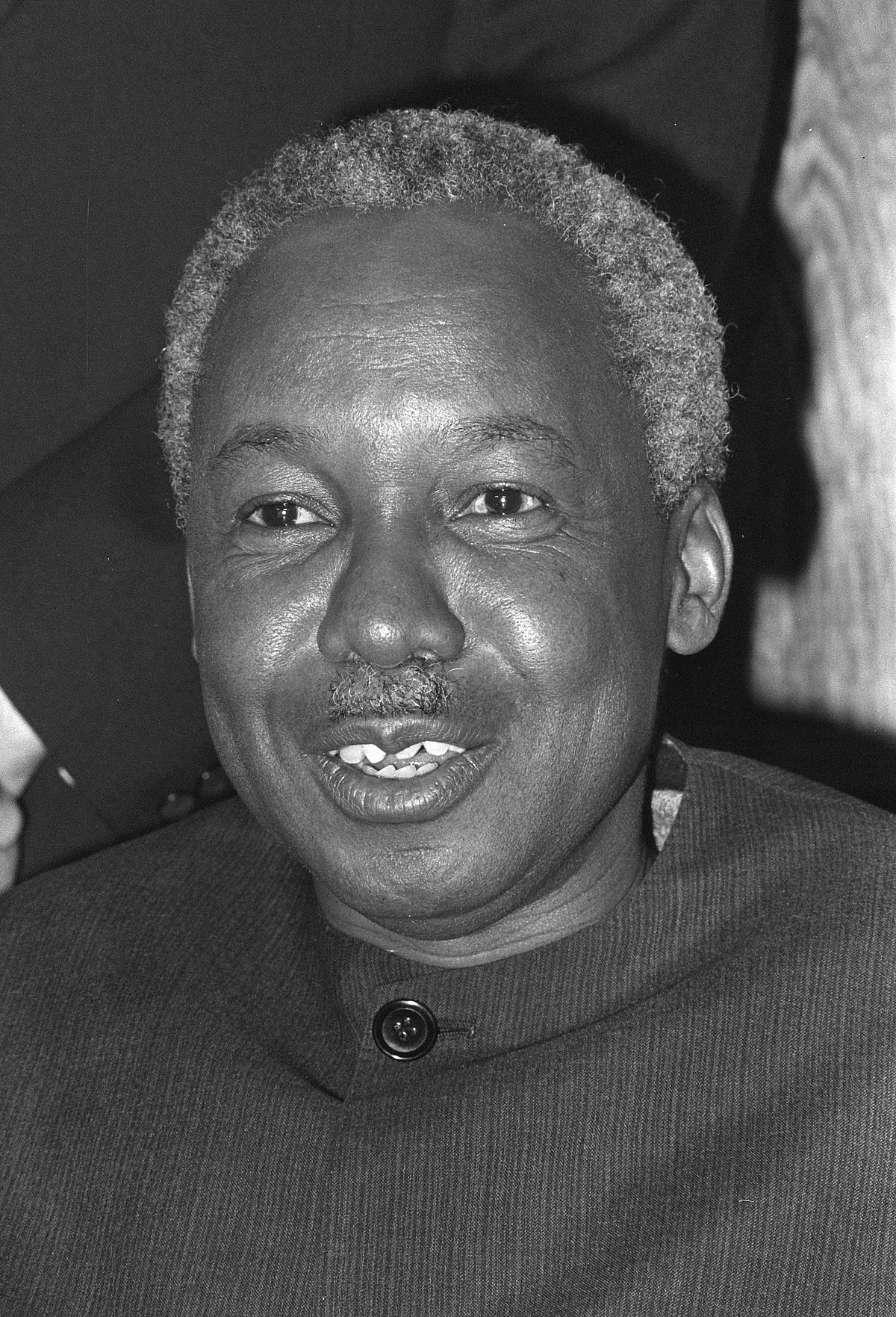

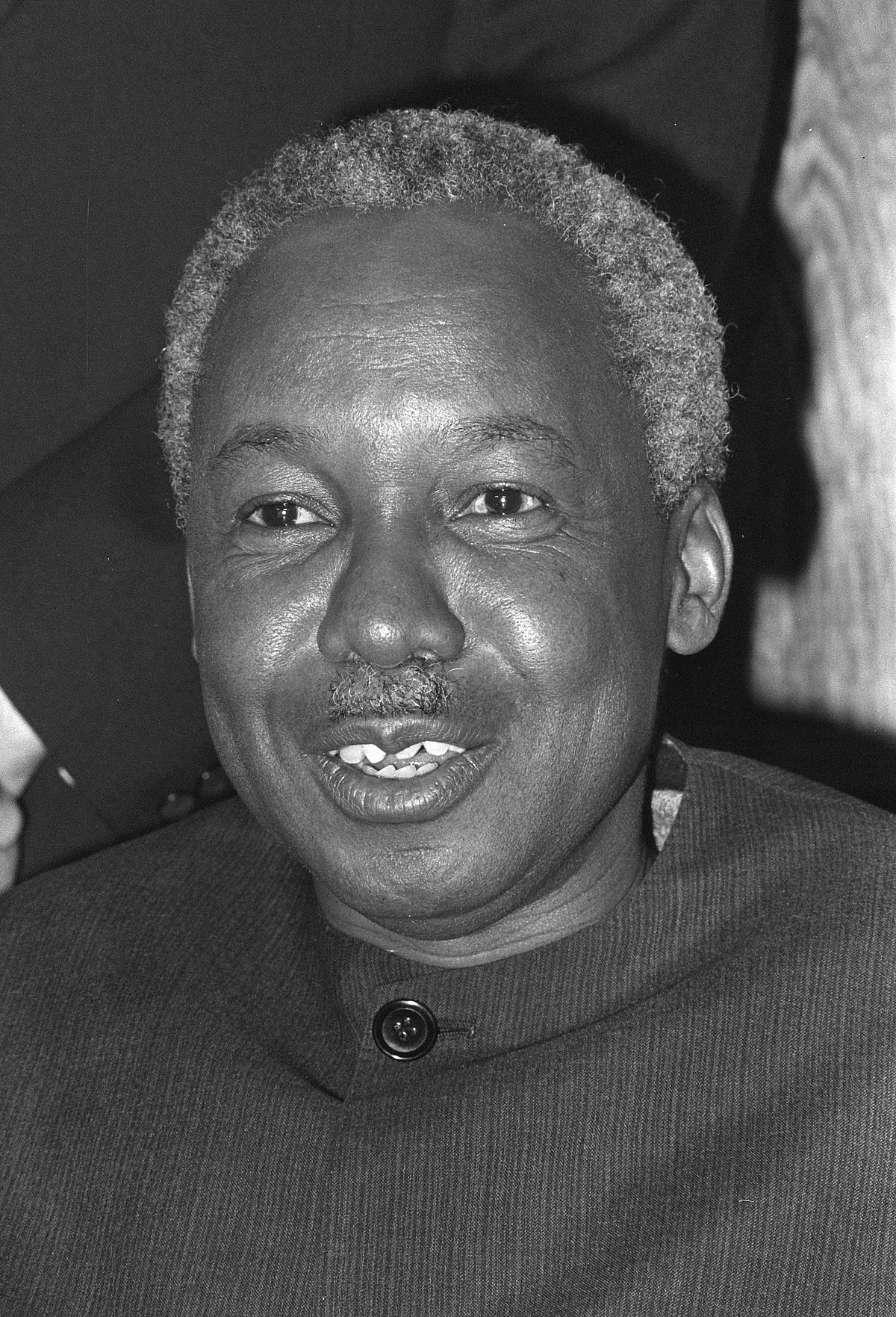

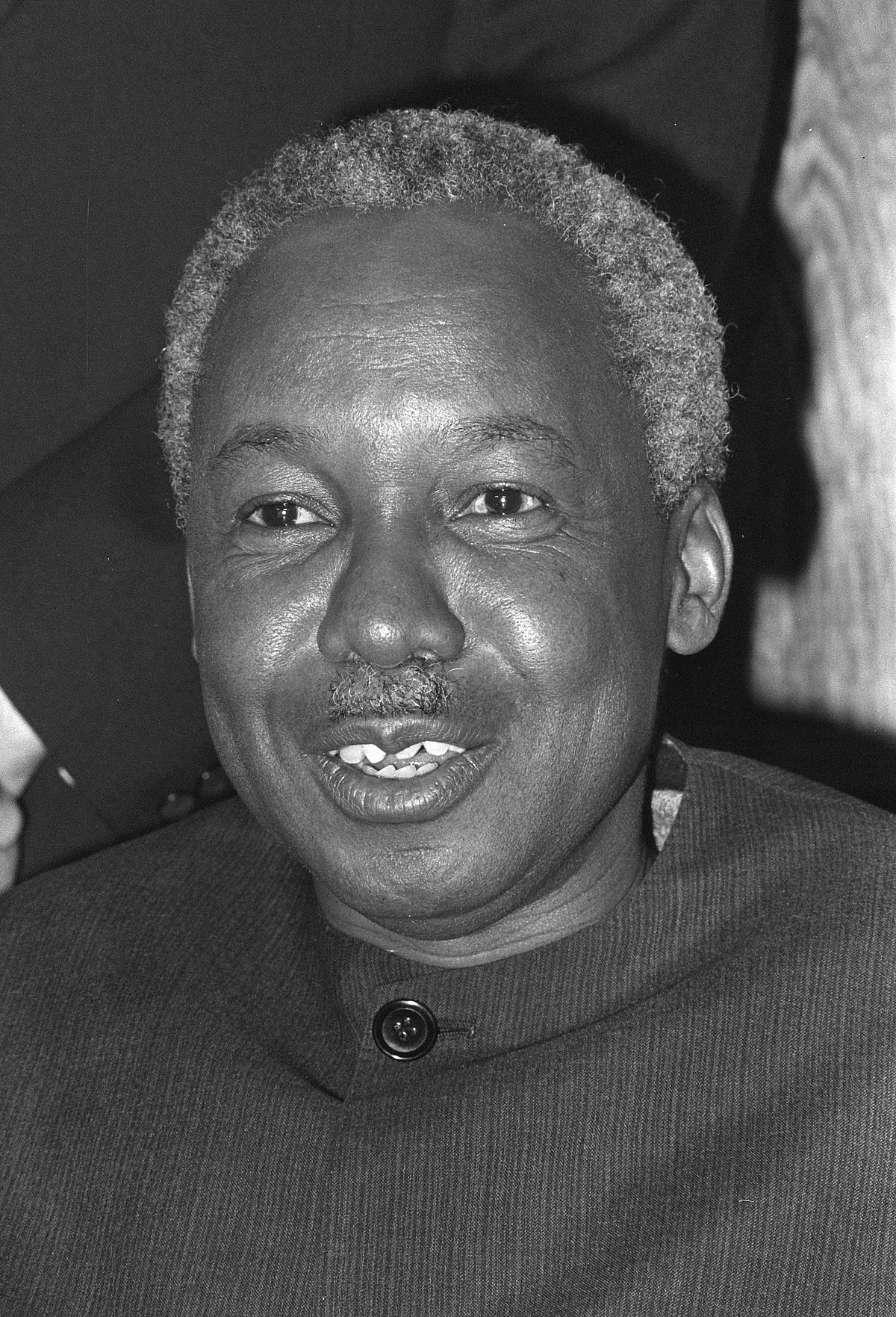

1. Julius Nyerere governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, after which he led its successor state, Tanzania, as president from 1964 to 1985.

1.

1. Julius Nyerere governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, after which he led its successor state, Tanzania, as president from 1964 to 1985.

Julius Nyerere was a founding member and chair of the Tanganyika African National Union party and of its successor, Chama Cha Mapinduzi, from 1954 to 1990.

In 1962, Tanganyika became a republic, with Julius Nyerere elected as its first president.

Julius Nyerere's administration pursued decolonisation and the "Africanisation" of the civil service while promoting unity between indigenous Africans and the country's Asian and European minorities.

Julius Nyerere encouraged the formation of a one-party state and unsuccessfully pursued the Pan-Africanist formation of an East African Federation with Uganda and Kenya.

In 1967, Julius Nyerere issued the Arusha Declaration which outlined his vision of ujamaa.

In 1985, Julius Nyerere stood down and was succeeded by Ali Hassan Mwinyi, who reversed many of Julius Nyerere's policies.

Julius Nyerere remained chair of Chama Cha Mapinduzi until 1990, supporting a transition to a multi-party system, and later served as mediator in attempts to end the Burundian Civil War.

Julius Kambarage Nyerere was born on 13 April 1922 in Mwitongo, an area of the village of Butiama in Tanganyika's Mara Region.

Julius Nyerere was one of 25 surviving children of Nyerere Burito, the chief of the Zanaki people.

Julius Nyerere had been born in 1892 and had married the chief in 1907, when she was fifteen.

Mugaya bore Burito four sons and four daughters, of which Julius Nyerere was the second child; two of his siblings died in infancy.

At birth, Julius Nyerere was given the personal name "Mugendi" but this was changed to "Kambarage", the name of a female rain spirit, at the advice of a omugabhu diviner.

Julius Nyerere was raised into the polytheistic belief system of the Zanaki, and lived at his mother's house, assisting in the farming of the millet, maize and cassava.

Julius Nyerere's education was in Swahili, a language he had to learn while there.

Julius Nyerere excelled at the school, and after six months his exam results were such that he was allowed to skip a grade.

Julius Nyerere avoided sporting activities and preferred to read in his dormitory during free time.

Julius Nyerere began to take an interest in Roman Catholicism, although was initially concerned about abandoning the veneration of his people's traditional gods.

Julius Nyerere used books in the school library to advance his knowledge of the English language to a high standard.

Julius Nyerere was heavily involved in the school's debating society, and teachers recommended him as head prefect, but this was vetoed by the headmaster, who described Nyerere as being "too kind" for the position.

In keeping with Zanaki custom, Julius Nyerere entered into an arranged marriage with a girl named Magori Watiha, who was then only three or four years old but had been selected for him by his father.

In October 1941, Julius Nyerere completed his secondary education and decided to study at Makerere College in the Ugandan city of Kampala.

Julius Nyerere secured a bursary to fund a teacher training course there, arriving in Uganda in January 1943.

Julius Nyerere took courses in chemistry, biology, Latin, and Greek.

Julius Nyerere won a literary competition with an essay on the subjugation of women, for which he had applied Mill's ideas to Zanaki society.

Julius Nyerere was an active member of the Makere Debating Society, and established a branch of Catholic Action at the university.

Julius Nyerere's letter went on to state that "the educated African should take the lead" in moving the population towards a more explicitly socialist model.

TAWA was allowed to die off, and in its place Julius Nyerere revived the largely moribund Makerere chapter of the Tanganyika African Association, although this too had ceased functioning by 1947.

On leaving Makerere, Julius Nyerere returned home to Zanaki territory to build a house for his widowed mother, before spending his time reading and farming in Butiama.

Julius Nyerere was offered teaching positions at both the state-run Tabora Boys' School and the mission-run St Mary's, but chose the latter despite it offering a lower wage.

Julius Nyerere took part in a public debate with two teachers from the Tabora Boys' School, in which he argued against the statement that "The African has benefitted more than the European since the partition of Africa"; after winning the debate, he was banned from returning to the school.

Julius Nyerere worked briefly as a price inspector for the government, going into stores to check what they were charging, although quit the position after the authorities ignored his reports about false pricing.

Julius Nyerere proposed marriage to her and they became informally engaged at Christmas 1948.

Walsh convinced Julius Nyerere to take the University of London's matriculation examination, which he passed with second division in January 1948.

Julius Nyerere applied for funding from the Colonial Development and Welfare Scheme and was initially unsuccessful, although succeeded on his second attempt, in 1949.

Julius Nyerere agreed to study abroad, although expressed some reluctance because it meant that he would no longer be able to provide for his mother and siblings.

Julius Nyerere then travelled, by train, from London to Edinburgh.

In 1949, Julius Nyerere was one of only two black students from the British East African territories studying in Scotland.

Julius Nyerere gained many friends in Edinburgh, and socialised with Nigerians and West Indians living in the city.

In July 1952, Julius Nyerere graduated from the university with an Ordinary Degree of Master of Arts.

Julius Nyerere took the train to Mwanza and then a lake steamer to Musoma before reaching Zanaki lands.

Julius Nyerere became increasingly involved in politics; in April 1953, he was elected president of the Tanganyika African Association.

Julius Nyerere himself was, according to Bjerk, "catapulted to prominence" as "a standard-bearer of the burgeoning independence movement".

On 7 July 1954 Julius Nyerere, assisted by Oscar Kambona, transformed the TAA into a new political party, the Tanganyika African National Union.

The colony's governor appointed Julius Nyerere to fill a temporary vacancy on its legislative council generated after David Makwaia was sent to London to serve on the Royal Commission for Land and Population Problems.

At TANU meetings, Julius Nyerere insisted on the need for Tanganyikan independence, but maintained that the country's European and Asian minorities would not be ejected by an African-led independent government.

Julius Nyerere greatly admired the Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi and endorsed Gandhi's approach to attaining independence through non-violent protest.

The UN was set to discuss the issue further at a trusteeship council in New York City, with TANU sending Julius Nyerere to be its representative there.

At the British government's request, the United States agreed to prevent Julius Nyerere staying for more than 24 hours before the meeting or moving outside an eight-block radius of the UN headquarters.

Julius Nyerere arrived in the city in March 1955, as part of a trip funded largely by Rupia.

On his return from New York, Julius Nyerere resigned from the school, in part because he did not wish his ongoing employment to cause trouble for the missionaries.

Julius Nyerere turned down offers of employment from a newspaper and an oil company, instead accepting a job as a translator and tutor for the Maryknoll Fathers, who were preparing a mission amongst the Zanaki.

The British colonial Governor of Tanganyika, Edward Twining, disliked Julius Nyerere, regarding him as a racialist who wanted to impose indigenous domination over the European and South Asian minorities.

Julius Nyerere nevertheless stipulated that "we are fighting against colonialism, not against the whites".

Julius Nyerere befriended members of the white minority, such as Lady Marion Chesham, a US-born widow of a British farmer, who served as a liaison between TANU and Twining's government.

At a January 1958 conference in Tabora, Julius Nyerere convinced TANU to take part.

Julius Nyerere stood as TANU's candidate in the Eastern Province seat against an independent candidate, Patrick Kunambi, securing 2600 votes to Kunambi's 800.

Julius Nyerere suggested that Tanganyika could delay its attainment of independence from the British Empire until neighbouring Kenya and Uganda were able to do the same.

Six weeks after independence, in January 1962 Julius Nyerere resigned as prime minister, intent on focusing on restructuring TANU and trying to "work out our own pattern of democracy".

Julius Nyerere toured the country, giving speeches in towns and villages in which he emphasised the need for self-reliance and hard work.

Julius Nyerere wrote an article, "Ujamaa" in which he explained and praised this policy; in this article he expressed many of his ideas about African socialism.

Julius Nyerere acknowledged that such affirmative action was discriminatory towards white and Asian citizens, but argued that it was temporarily necessary to redress the imbalance caused by colonialism.

Julius Nyerere avoided becoming personally embroiled in these controversies, which brought accusations of government hypersensitivity from some foreign media.

Julius Nyerere defended this measure, pointing to similar laws in the United Kingdom and India, and stating that the government needed it as a safeguard given the weak state of both the police and army.

Julius Nyerere expressed the hope that the government would never have to use it, and noted that they were aware how it "could be a convenient tool in the hands of an unscrupulous government".

Biographer William Edgett Smith later noted that it was "a foregone conclusion" that Julius Nyerere would be selected as TANU's candidate for president.

Julius Nyerere stipulated that "complete political amnesty" should be granted to anyone expelled from the party since 1954, allowing them to rejoin.

Julius Nyerere welcomed Asians and Europeans into the cabinet to counter potential racial resentment from these minorities.

Julius Nyerere saw it as importance to build a "national consciousness" that transcended ethnic and religious lines.

Julius Nyerere moved into the State House in Dar es Salaam, the former official residence of British governors.

Julius Nyerere disliked life in the building, but remained there until 1966.

Julius Nyerere made official visits to West Germany, the United States, Canada, Algeria, Scandinavia, Guinea, and Nigeria.

The early years of Julius Nyerere's presidency were preoccupied largely by African affairs.

Julius Nyerere endorsed the Pan-Africanist idea of unifying Africa as a single state, although he disagreed with the Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah's view that this could be achieved quickly.

In December 1963, Julius Nyerere lamented that this failure was the major disappointment of the year.

Later, Julius Nyerere saw his inability to establish an East African Federation as the biggest failure of his career.

Julius Nyerere was concerned by developments in Zanzibar, a pair of islands off of Tanganyika's coast.

Julius Nyerere noted that it was "very vulnerable to outside influences", which could in turn impact Tanganyika.

Julius Nyerere was keen to keep Cold War conflicts between the US and Soviet Union out of eastern Africa.

In January 1964, Julius Nyerere ended affirmative action hiring for the civil service.

Julius Nyerere narrowly escaped, hiding in a Roman Catholic mission for two days.

Julius Nyerere denounced the ringleaders of the mutiny for trying to "intimidate our nation at the point of a gun", and fourteen of them were given sentences of between five and fifteen years imprisonment.

Julius Nyerere was angry at this Western response as well as the wider Western failure to appreciate why black Zanzibaris had revolted in the first place.

Julius Nyerere was a source of repeated embarrassment to Nyerere, who tolerated him for the sake of Tanzanian unity.

Julius Nyerere was further embarrassed by the habit of Karume and other Zanzibari Revolutionary Council members for pressuring Arab girls into marriage and then arresting their relatives to ensure compliance.

Julius Nyerere spoke to the crowd in defence of the measure, and agreed to reduce government salaries, including his own.

That year, Julius Nyerere ceased using State House as his permanent residence, moving into a newly built private home on the seafront at Msasani.

In February 1965, Julius Nyerere made an eight-day state visit to China, opining that their socio-economic projects in moving an agrarian country towards socialism had much relevance for Tanzania.

Julius Nyerere was fascinated by Mao's China because it espoused the egalitarian values he shared; he was inspired by the government's emphasis on frugality and economy.

Julius Nyerere wrote an introduction for Not Yet Uhuru, the 1967 autobiography of Kenyan leftist politician Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

Julius Nyerere's Tanzania welcomed various liberation groups from southern Africa, such as FRELIMO, to set up operations in the country to work towards overthrowing the colonial and white-minority governments of these countries.

Julius Nyerere's government had warm relations with the neighbouring Zambian government of Kenneth Kaunda.

Julius Nyerere strongly disapproved of Banda's co-operation with the Portuguese colonial governments in Angola and Mozambique and the white minority governments of Rhodesia and South Africa.

In 1967, Julius Nyerere's government was the first to grant recognition of the newly declared Republic of Biafra, which had seceded from Nigeria.

In September 1965, Julius Nyerere threatened to withdraw from the Commonwealth if Britain's government negotiated for the independence of Rhodesia with Ian Smith's white minority government rather than with representatives of the country's black majority.

Julius Nyerere stressed that British Tanzanians remained welcome in the country and that violence towards them would not be tolerated.

In January 1967, Julius Nyerere attended a TANU National Executive meeting at Arusha.

Julius Nyerere followed his declaration with a series of additional policy papers covering such areas as foreign policy and rural development.

Julius Nyerere had been inspired by the example of the Ruvuma Development Association, an agricultural commune formed in 1962, and believed its example could be followed throughout Tanzania.

Julius Nyerere saw this as necessary to stem the growth of corruption in Tanzania; he was aware of how this problem had become endemic in some African countries like Nigeria and Ghana and regarded it as a threat to his vision of African freedom.

In 1969, Julius Nyerere sponsored a bill to provide gratuities for ministers and regional and area commissioners which could be used as a retirement income for them.

Julius Nyerere decided not to push the issue, conceding that parliament had valid concerns.

In 1969, Julius Nyerere informed a journalist that he was contemplating retirement from the presidency, hoping to encourage new leadership, although at the same time had a desire to remain in place to oversee the implementation of his ideas.

Julius Nyerere's government established a Ministry of National Culture and Youth through which to encourage the growth of a distinctly Tanzanian culture.

Juxtaposing idealised rural lifestyles against urban lifestyles which were labelled "decadent", Julius Nyerere's government launched its Operation Vijana in October 1968.

Julius Nyerere believed that homosexuality was alien to Africa and thus Tanzania did not need to legislate against the discrimination of homosexuals.

Julius Nyerere rarely initiated such detentions personally, although had the final say on all such arrests.

Julius Nyerere then claimed to have been the victim of a plot to overthrow Nyerere orchestrated by a group opposed to the Arusha Declaration.

Julius Nyerere was angered by these statements and asked Kambona to return.

Julius Nyerere spoke of the Zanaki concept of kung'atuka, which meant the leaders passing on control to a younger generation.

Julius Nyerere proposed that having TANU govern the mainland and ASP govern Zanzibar contravened the concept of a one-party state and called for their merger.

In 1977, Julius Nyerere made his second state visit to the US, where President Jimmy Carter hailed him as "a senior statesman whose integrity is unquestioned".

Julius Nyerere remained committed to backing anti-colonialist groups throughout southern Africa, including those fighting the white minority governments in Southern Rhodesia and South Africa and the Portuguese colonial administrations in Mozambique and Angola.

Julius Nyerere refused to recognise the legitimacy of Amin's administration and offered Obote refuge in Tanzania.

Shortly after the coup, Julius Nyerere announced the formation of a "people's militia", a type of home guard to improve Tanzania's national security.

Julius Nyerere allowed exiled Ugandans to set up rebel bases in Tanzania.

One boatload of Ugandan Asian refugees attempted to land in Tanzania, although Julius Nyerere's government refused to permit them, concerned that it would stoke domestic racial tensions.

Julius Nyerere rejected his generals' urges to respond with force and agreed to Somali mediation, which resulted in the signing of a peace agreement between Uganda and Tanzania.

Julius Nyerere decided that Tanzania's response should be not only to push the Uganda Army back into Uganda, but to invade the latter and overthrow Amin.

Julius Nyerere was appalled and ordered measures to ensure the Tanzanians would not attack civilian targets in future.

Julius Nyerere lobbied foreign ambassadors to cut off supplies of oil and weapons to Uganda.

Julius Nyerere accepted this advice, and when organising a March 1979 conference for exile groups in Moshi convinced Obote not to attend.

Julius Nyerere withdrew most of the Tanzanian army, leaving only a small training contingent, although Uganda entered a cycle of civil wars until 1986.

Julius Nyerere viewed the IMF as a neocolonial tool which imposed policies on poorer countries that benefitted their wealthier counterparts.

Julius Nyerere took an active role in trying to find a successor.

One of his favourites was the Zanzibari Seif Sharif Hamad, whom Julius Nyerere brought into the CCM's Central Committee.

Julius Nyerere stood down as president, with Mwinyi replacing him at the 1985 general election.

Julius Nyerere remained chair of CCM until 1990 and from this position became a vocal critic of Mwinyi's policies.

Julius Nyerere saw these reforms as an abandonment of his socialist ideals.

In July 1987, Julius Nyerere returned to the University of Edinburgh to attend a conference on "The Making of Constitutions and the Development of National Identity", where he gave the opening address on post-independence Africa.

Julius Nyerere was invited to chair an international committee on the economic problems facing the "Global South", where he worked alongside the future Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

Julius Nyerere believed that the CCM had become too hidebound and corrupt and that competition with other parties would force it to improve.

Julius Nyerere argued that there was no evidence it would improve government and that it would waste tax-payer's money.

In 1992, the Zanzibari government joined the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, something Julius Nyerere criticised, arguing that foreign affairs was a federal issue and should not be delegated to the Zanzibari state.

In 1993,55 mainland parliamentarians called for the establishment of a mainland regional government, which Julius Nyerere attacked in a pamphlet the following year.

Julius Nyerere expressed concerns about growing mainland chauvinism as a response to Zanzibari separatism and argued that it would develop into tribal resentments and rivalries.

Julius Nyerere campaigned in support of the CCM candidates in Tanzania's 1995 presidential election.

Julius Nyerere remained active in international affairs, attending the 1994 Pan-African Congress, held in the Ugandan city of Kampala.

Julius Nyerere pointed to the example of growing European unity within the European Union as a model for African states to imitate.

In 1996 the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Foundation was established though which the negotiations could take place; it was modelled on the US Carter Center.

Julius Nyerere was adamant that a resolution for peace should arise from a regional initiative rather than one brought forth by the Western powers.

Julius Nyerere insisted on a process of inclusivity, with even the smallest political groups being invited to take part in the negotiation process, and emphasised the construction of civilian political institutions as key to a lasting peace in Burundi.

Julius Nyerere died on 14 October 1999, with his wife and six of his children at his bedside.

Julius Nyerere was honoured by Tanzanian state radio playing funeral music while video footage of him were broadcast on television.

Julius Nyerere's body was then flown back to Tanzania, where it was carried past crowds in Dar es Salaam and taken to his coastal home.

The political economist Issa G Shivji noted that although Nyerere was "a great man of principle" but that when in power, "at times pragmatism, even Machiavellism, overshadowed his avowed principles".

Julius Nyerere despised colonialism, and felt duty bound to oppose the colonial state in Tanganyika.

In campaigning against colonialism, Julius Nyerere acknowledged that he was inspired by the principles behind both the American Revolution and the French Revolution.

Julius Nyerere was influenced by the Indian independence movement, which successfully resulted in the creation of an Indian republic in 1947, just before Nyerere studied in Britain.

When in power, Julius Nyerere ensured that his government and close associates reflected a cross-section of East African society, including black Africans, Indians, Arabs, and Europeans, as well as practitioners of Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and African traditional religion.

Julius Nyerere nevertheless saw a tension between his governance of a nation-state and his Pan-Africanist values, referring to this as "dilemma of the pan-Africanist" in a 1964 address.

Julius Nyerere absorbed the values of liberal democracy but focused attention on how to "Africanize" democracy.

Julius Nyerere emphasized that post-colonial African states were in a very different situation to Western countries and thus required a different governance structure; specifically, he favoured a representative democratic system within a one-party state.

Julius Nyerere opposed the formation of different parties and other political organisations with differing objectives in Tanzania, deeming them disruptive to his idea of the harmonious society and fearing their ability to further destabilise the fragile state.

Julius Nyerere criticised the de facto two-party system he had observed in Britain, describing it as "foot-ball politics".

For Julius Nyerere, it was the preservation of political and civil liberties, rather than the presence of multiple parties, that ensured democracy; he believed that freedom of speech was possible in a one-party state.

Julius Nyerere was keen to associate himself with the idea of freedom, titling his three major compilations of speeches and writings Freedom and Unity, Freedom and Socialism, and Freedom and Development.

Julius Nyerere was one of the signatories of the agreement to convene a convention for drafting a world constitution.

At the heart and centre of Julius Nyerere's political values was an affirmation of the fundamental equality of all humankind and a commitment to the building of social, economic and political institutions which would reflect and ensure this equality.

Julius Nyerere was a socialist, with his views on socialism intertwined with his ideas on democracy.

Julius Nyerere promoted African socialism from at least July 1943, when he wrote an article referring to the concept in the Tanganyika Standard newspaper.

Julius Nyerere saw socialism not as an alien idea to Africa but as something that reflected traditional African lifestyles.

Molony described Julius Nyerere as having produced "romanticised accounts of idyllic village life in 'traditional society'", describing his as "a misty-eyed view" of this African past.

In most of Africa, Julius Nyerere said, "we have to begin our socialism from tribal communalism and a colonial legacy which did not build much capitalism".

Julius Nyerere was critical of the utopian socialism promoted by figures like Henri de Saint-Simon and Robert Owen, seeing their ideas as largely irrelevant to the Tanzanian situation.

Julius Nyerere firmly believed in egalitarianism and in creating a society of equals, referring to his desire for a "classless society".

Julius Nyerere desired a society in which the interests of the individual and society were identical and thought this could be achieved because individuals ultimately wanted to promote the common good.

Julius Nyerere believed it important to balance the rights of the individual with their duty to society, expressing the view that Western countries placed too much of an emphasis on individual rights; he regarded what he saw as the ensuing self-centred materialism as repulsive.

Julius Nyerere detested elitism and sought to reflect that attitude in the manner in which he conducted himself as president.

Julius Nyerere was cautious to prevent the replacement of the colonial elite with an indigenous elite, and to this end insisted that the most educated sectors of the Tanzanian population should remain fully integrated with society as a whole.

Julius Nyerere criticised the existence of aristocracy and the British monarchy.

Julius Nyerere remained dedicated to a belief in the rule of law.

Julius Nyerere appealed to the idea of tradition when trying to convince Tanzanians of his ideas.

Julius Nyerere stated that Tanzania could only be developed "through the religion of socialism and self-reliance".

Julius Nyerere reiterated the ideas of freedom, equality, and unity as being central to his concept of African socialism.

Trevor Huddleston thought that Julius Nyerere could be considered both a Christian humanist, and a Christian socialist.

Julius Nyerere was described as an eloquent speaker, and a skilled debater, with Bjerk describing him as having "a scholar's mind".

Smith noted that Julius Nyerere had a "respect for spartan living" and an "abhorrence of luxury"; in his later years he always travelled by economy class.

Huddleston recalled conversations with Julius Nyerere as being "exciting and stimulating", with the Tanzanian leader focusing on world issues rather than talking about himself.

In Huddleston's view, Julius Nyerere was "a great human being who has always treasured his human-ness more deeply than his office".

For Huddleston, Julius Nyerere displayed much humility, a trait that was "rare indeed" among politicians and statesmen.

When planners suggested infrastructure developments for his home area, Julius Nyerere rejected the proposals, not wanting to present the appearance of giving favours to it.

The style of suit that Julius Nyerere wore was widely imitated in Tanzania, which led to it being known as a "Tanzanian suit".

Julius Nyerere objected to the tendency in Western countries to view Africa through the prism of Cold War politics.

Julius Nyerere wrote poetry, and translated William Shakespeare's plays Julius Caesar and The Merchant of Venice into Swahili, publishing these in 1961 and 1972 respectively.

Julius Nyerere described Christianity as "a revolutionary creed" but believed that its message had often been corrupted by churches.

Julius Nyerere liked to attend Mass in the early mornings, and while in Edinburgh enjoyed spending time sitting quietly in church.

Julius Nyerere avoided Christian sectarianism and was friends with Christians of other denominations.

When Julius Nyerere was president, he insisted that his children go to state school and receive no special privileges.

In January 2005, the Diocese of Musoma opened the cause for the canonization of Julius Nyerere, who was a devout Catholic and a man of recognized integrity.

Julius Nyerere gained recognition for the successful merger between Tanganyika and Zanzibar, and for leaving Tanzania as a united and stable state.

Molony noted that Julius Nyerere was "often depicted as Tanganyika's wunderkind", and is "remembered as one of Africa's most respected statesmen".

Smith noted that through his regular tours of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere "has probably spoken directly to as large a percentage of his countrymen as any head of state on earth".

In Pratt's view, Julius Nyerere had been "a leader of unquestionable integrity who whatever his policy errors, was profoundly committed" to the welfare of his people.

Richard Turnbull, the last British governor of Tanganyika, described Julius Nyerere as having "a tremendous adherence to principle" and exhibiting "rather a Gandhian streak".

For Kosukhin, Julius Nyerere was "a recognized standard bearer of the struggle for African liberation and a tireless champion of the idea of equitable economic relations between the rich North and the developing South".

Posthumously, the Catholic Church in Tanzania began the processing of beatifying Julius Nyerere, hoping to have him recognised as a saint.

At his death, Western commentators repeatedly claimed that Julius Nyerere had served his people poorly as president.

Bjerk noted that although Julius Nyerere was "an advocate for democracy", his pursuit of a democracy adapted to East African society led to him forming "a one-party state that regularly violated democratic values".