1.

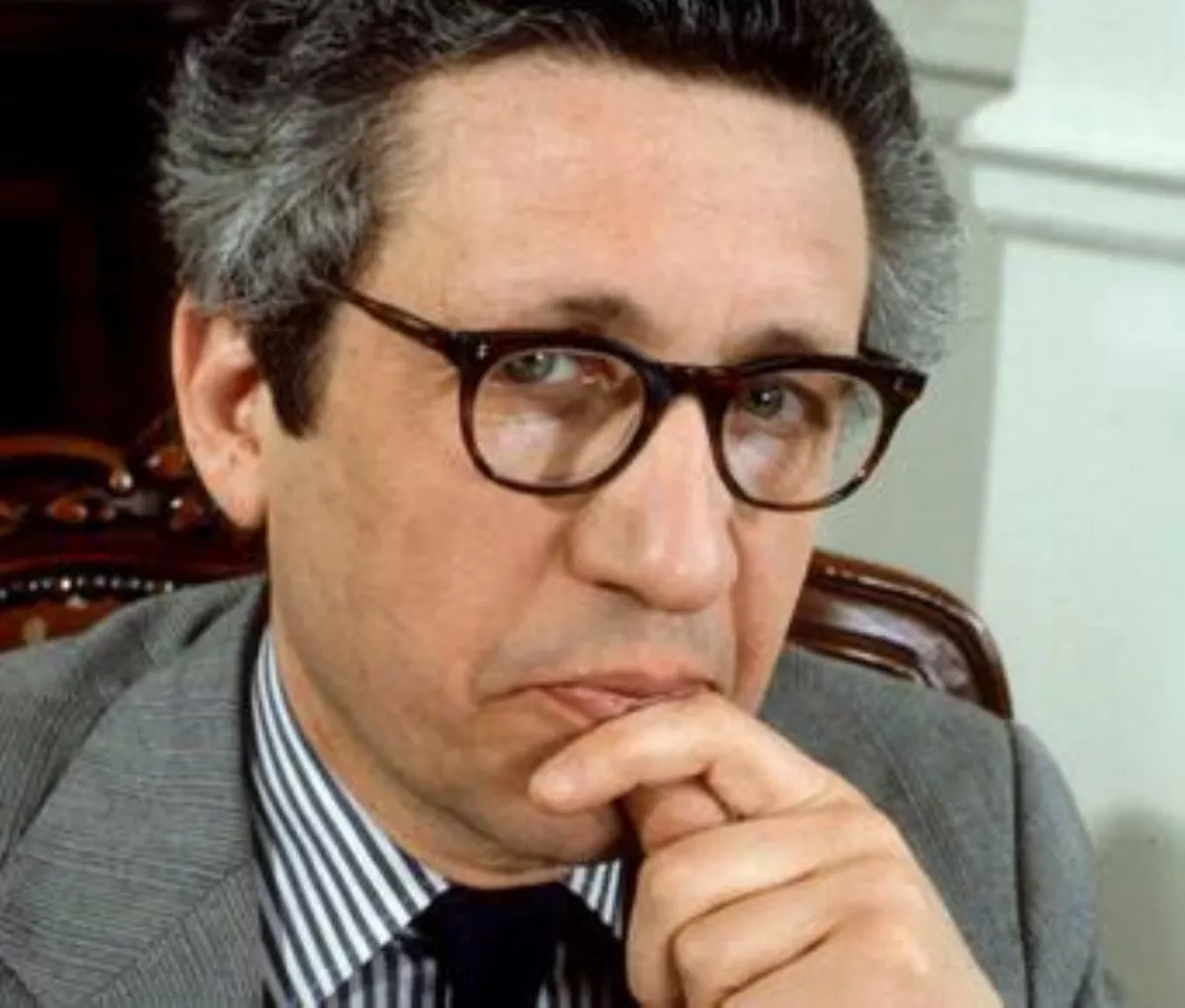

1. Bernard Levin became a broadcaster, first on the weekly satirical television show That Was the Week That Was in the early 1960s, then as a panellist on a musical quiz, Face the Music, and finally in three series of travel programmes in the 1980s.