1.

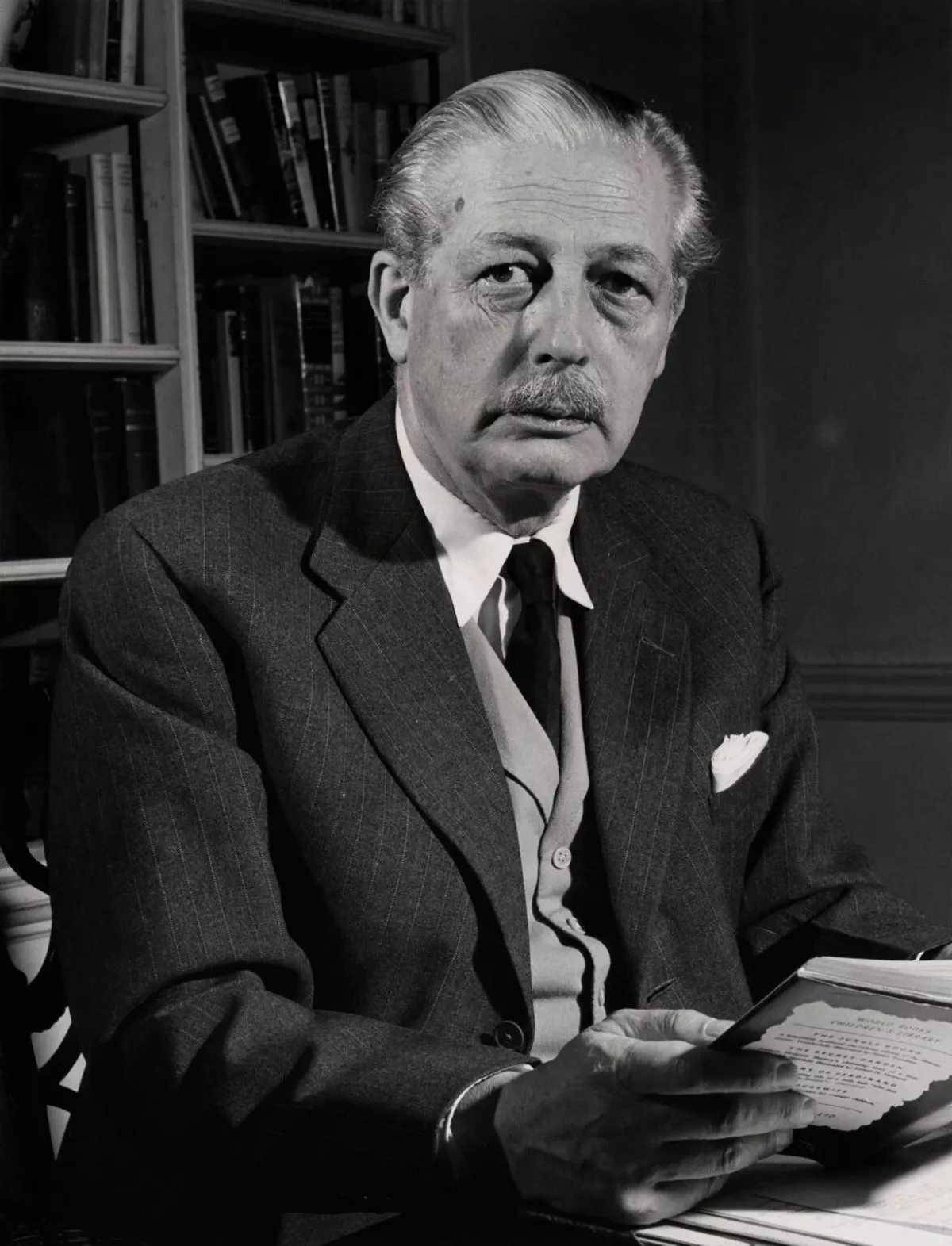

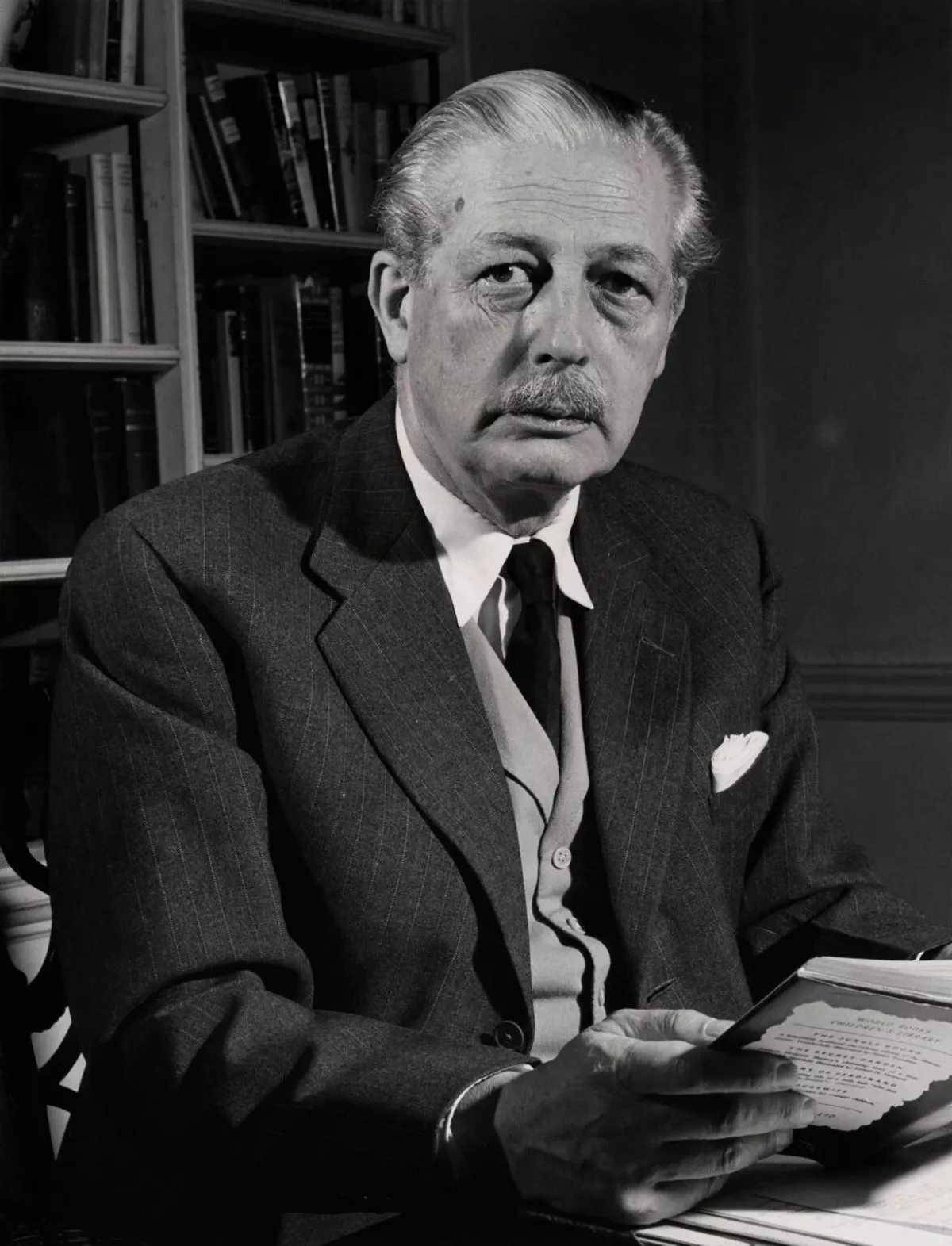

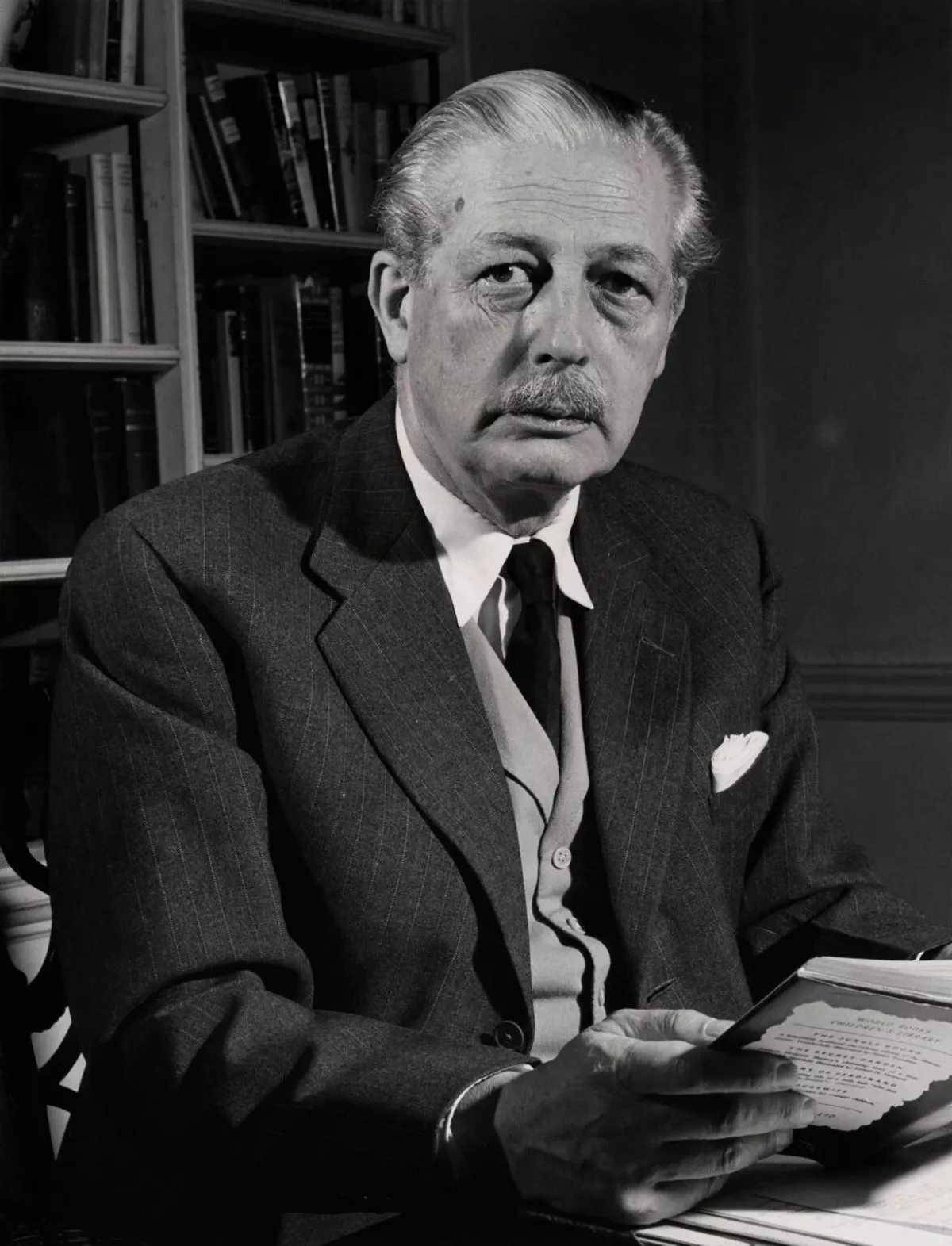

1. Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963.

1.

1. Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963.

Harold Macmillan suffered pain and partial immobility for the rest of his life.

Harold Macmillan opposed the appeasement of Germany practised by the Conservative government.

Harold Macmillan rose to high office during the Second World War as a protege of Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

When Eden resigned in 1957 following the Suez Crisis, Harold Macmillan succeeded him as prime minister and Leader of the Conservative Party.

Harold Macmillan was a One Nation Tory of the Disraelian tradition and supported the post-war consensus.

Harold Macmillan supported the welfare state and the necessity of a mixed economy with some nationalised industries and strong trade unions.

Harold Macmillan championed a Keynesian strategy of deficit spending to maintain demand and pursuit of corporatist policies to develop the domestic market as the engine of growth.

Harold Macmillan led the Conservatives to success in 1959 with an increased majority.

In international affairs, Harold Macmillan worked to rebuild the Special Relationship with the United States from the wreckage of the 1956 Suez Crisis, and facilitated the decolonisation of Africa.

Harold Macmillan died in December 1986 at the age of 92.

Harold Macmillan was born on 10 February 1894, at 52 Cadogan Place in Chelsea, London, to Maurice Crawford Harold Macmillan, a publisher, and the former Helen Artie Tarleton Belles, an artist and socialite from Spencer, Indiana.

Harold Macmillan had two brothers, Daniel, eight years his senior, and Arthur, four years his senior.

Harold Macmillan received an intensive early education, closely guided by his American mother.

Harold Macmillan learned French at home every morning from a succession of nursery maids, and exercised daily at Mr Macpherson's Gymnasium and Dancing Academy, around the corner from the family home.

Harold Macmillan was Third Scholar at Eton College, but his time there was blighted by recurrent illness, starting with a near-fatal attack of pneumonia in his first half ; he missed his final year after being taken ill, and was taught at home by private tutors, notably Ronald Knox, who did much to instil his High Church Anglicanism.

Harold Macmillan won an exhibition to Balliol College, Oxford.

Harold Macmillan went up to Balliol College in 1912, where he joined many political societies.

Harold Macmillan read avidly about Disraeli, but was particularly impressed by a speech by Lloyd George at the Oxford Union Society in 1913, where he had become a member.

Harold Macmillan was a protege of the president of the Union Society Walter Monckton, later a Cabinet colleague; as such, he became secretary then junior treasurer of the Union, and would in his biographers' view "almost certainly" have been president had the war not intervened.

Harold Macmillan fought on the front lines in France, where the casualty rate was high, including the probability of an "early violent death".

Harold Macmillan served with distinction and was wounded on three occasions.

Harold Macmillan then returned to the front lines in France.

Harold Macmillan spent the final two years of the war in King Edward VII's Hospital in Grosvenor Gardens undergoing a series of operations.

Harold Macmillan was still on crutches at the Armistice of 11 November 1918.

However, at the end of 1918 Harold Macmillan joined the Guards Reserve Battalion at Chelsea Barracks for "light duties".

Harold Macmillan then served in Ottawa, Canada, in 1919 as aide-de-camp to Victor Cavendish, 9th Duke of Devonshire, then Governor General of Canada, and his future father-in-law.

Harold Macmillan resigned from the company on appointment to ministerial office in 1940.

Harold Macmillan resumed working with the firm from 1945 to 1951 when the party was in opposition.

Harold Macmillan married Lady Dorothy Cavendish, the daughter of the 9th Duke of Devonshire, on 21 April 1920.

Harold Macmillan's great-uncle was Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, who was leader of the Liberal Party in the 1870s, and a close colleague of William Ewart Gladstone, Joseph Chamberlain and Lord Salisbury.

Harold Macmillan was often treated with condescension by his aristocratic in-laws and was observed to be a sad and isolated figure at Chatsworth in the 1930s.

In old age, Harold Macmillan was a close friend of Ava Anderson, Viscountess Waverley, nee Bodley, the widow of John Anderson, 1st Viscount Waverley.

Eileen O'Casey, nee Reynolds, the actress wife of Irish dramatist Sean O'Casey, was another female friend, Harold Macmillan publishing her husband's plays.

Harold Macmillan contested the depressed northern industrial constituency of Stockton-on-Tees in 1923.

In 1927, four MPs, including Boothby and Harold Macmillan, published a short book advocating radical measures.

In 1928, Harold Macmillan was described by his political hero, and now Parliamentary colleague, David Lloyd George, as a "born rebel".

Harold Macmillan lost his seat in 1929 in the face of high regional unemployment.

Harold Macmillan almost became Conservative candidate for the safe seat of Hitchin in 1931.

Harold Macmillan advocated cheap money and state direction of investment.

Harold Macmillan resigned the government whip in protest at the lifting of sanctions on Italy after her conquest of Abyssinia.

The Next Five Years Group, to which Harold Macmillan had belonged, was wound up in November 1937.

Harold Macmillan took control of the magazine New Outlook and made sure it published political tracts rather than purely theoretical work.

In 1936, Harold Macmillan proposed the creation of a cross-party forum of antifascists to create democratic unity but his ideas were rejected by the leadership of both the Labour and Conservative parties.

Harold Macmillan supported Chamberlain's first flight for talks with Hitler at Berchtesgaden, but not his subsequent flights to Bad Godesberg and Munich.

Harold Macmillan supported the independent candidate, Lindsay, at the 1938 Oxford by-election.

Harold Macmillan visited Finland in February 1940, then the subject of great sympathy in Britain as it was being invaded by the USSR, then loosely allied to Nazi Germany.

Harold Macmillan finally attained office by serving in the wartime coalition government as the Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Supply from 1940.

Harold Macmillan's job was to provide armaments and other equipment to the British Army and Royal Air Force.

Harold Macmillan travelled up and down the country to co-ordinate production, working with some success under Lord Beaverbrook to increase the supply and quality of armoured vehicles.

Harold Macmillan was appointed Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1942, in his own words "leaving a madhouse to enter a mausoleum".

Harold Macmillan was given responsibility for increasing colonial production and trade, and signalled the future policy direction when in June 1942 he declared:.

In October 1942 Harold Nicolson recorded Macmillan as predicting "extreme socialism" after the war.

Harold Macmillan nearly resigned when Oliver Stanley was appointed Secretary of State in November 1942, as he would no longer be the spokesman in the Commons as he had been under Cranborne.

Harold Macmillan reported directly to the Prime Minister instead of to the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden.

At the Casablanca Conference Harold Macmillan helped to secure US acceptance, if not recognition, of the Free French leader Charles de Gaulle.

Harold Macmillan wrote in his diary during the Casablanca conference: "I christened the two personalities the Emperor of the East and the Emperor of the West and indeed it was rather like a meeting of the late Roman empire".

On 22 February 1943, Harold Macmillan was badly burned in a plane crash, trying to climb back into the plane to rescue a Frenchman.

Harold Macmillan had to have a plaster cast put on his face.

Harold Macmillan was based at Caserta for the rest of the war.

Harold Macmillan was appointed UK High Commissioner for the Advisory Council for Italy late in 1943.

Harold Macmillan visited London in October 1943 and again clashed with Eden.

In May 1944 Harold Macmillan infuriated Eden by demanding an early peace treaty with Italy, a move which Churchill favoured.

On 14 September 1944 Harold Macmillan was appointed Chief Commissioner of the Allied Control Commission for Italy.

Harold Macmillan continued to be British Minister Resident at Allied Headquarters and British political adviser to "Jumbo" Wilson, now Supreme Commander, Mediterranean.

Harold Macmillan rode in a tank and was under sniper fire at the British Embassy.

Harold Macmillan was the minister advising General Keightley of V Corps, the senior Allied commander in Austria responsible for Operation Keelhaul, which included the forced repatriation of up to 70,000 prisoners of war to the Soviet Union and Josip Broz Tito's Yugoslavia in 1945.

Harold Macmillan toyed with an offer to succeed Duff Cooper as MP for the safe Conservative seat of Westminster St George's.

However, it was thought better for him to be seen to defend his seat, and Lord Beaverbrook had already spoken to Churchill to arrange that Harold Macmillan be given another seat in the event of defeat.

Harold Macmillan returned to England after the European war, feeling himself 'almost a stranger at home'.

Harold Macmillan indeed lost Stockton in the landslide Labour victory of July 1945, but returned to Parliament in the November 1945 by-election in Bromley.

In July 1953 Harold Macmillan considered postponing his gall bladder operation in case Churchill, who had just suffered a serious stroke while Eden was in hospital, had to step down.

Harold Macmillan achieved his housing target by the end of 1953, a year ahead of schedule.

Harold Macmillan was Minister of Defence from October 1954, but found his authority restricted by Churchill's personal involvement.

Harold Macmillan was one of the few ministers brave enough to tell Churchill to his face that it was time for him to retire.

Harold Macmillan is forever poised between the cliche and the indiscretion.

Harold Macmillan was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in December 1955.

Harold Macmillan had enjoyed his eight months as Foreign Secretary and did not wish to move.

Harold Macmillan insisted on being "undisputed head of the home front" and that Eden's de facto deputy Rab Butler, whom he was replacing as Chancellor, not have the title "Deputy Prime Minister" and not be treated as senior to him.

Harold Macmillan even tried to demand that Salisbury, not Butler, should preside over the Cabinet in Eden's absence.

Harold Macmillan later claimed in his memoirs that he had still expected Butler, his junior by eight years, to succeed Eden, but correspondence with Lord Woolton at the time makes clear that Harold Macmillan was very much thinking of the succession.

Harold Macmillan planned to reverse the 6d cut in income tax which Butler had made a year previously, but backed off after a "frank talk" with Butler, who threatened resignation, on 28 March 1956.

Harold Macmillan settled for spending cuts instead, and himself threatened resignation until he was allowed to cut bread and milk subsidies, something the Cabinet had not permitted Butler to do.

Harold Macmillan threatened to resign if force was not used against Nasser.

Harold Macmillan was heavily involved in the secret planning of the invasion with France and Israel.

Harold Macmillan met Eisenhower privately on 25 September 1956 and convinced himself that the US would not oppose the invasion, despite the misgivings of the British Ambassador, Sir Roger Makins, who was present.

In later life Harold Macmillan was open about his failure to read Eisenhower's thoughts correctly and much regretted the damage done to Anglo-American relations, but always maintained that the Anglo-French military response to the nationalisation of the Canal had been for the best.

Harold Macmillan tried, but failed, to see Eisenhower behind Butler's and Eden's back.

Harold Macmillan had a number of meetings with US Ambassador Winthrop Aldrich, in which he said that if he were prime minister the US Administration would find him much more amenable.

Harold Macmillan wrote "I held the Tory Party for the weekend, it was all I intended to do".

Harold Macmillan had further meetings with Aldrich and Winston Churchill after Eden left for Jamaica while briefing journalists that he planned to retire and go to the Lords.

Harold Macmillan was hinting that he would not serve under Butler.

Harold Macmillan had opposed Eden's trip to Jamaica and told Butler that younger members of the Cabinet wanted Eden out.

Harold Macmillan's political standing destroyed, Eden resigned on grounds of ill health on 9 January 1957.

Harold Macmillan silenced the klaxon on the Prime Ministerial car, which Eden had used frequently.

Harold Macmillan advertised his love of reading Anthony Trollope and Jane Austen, and on the door of the Private Secretaries' room at Number Ten he hung a quote from The Gondoliers: "Quiet, calm deliberation disentangles every knot".

Harold Macmillan filled government posts with 35 Old Etonians, seven of them in Cabinet.

Harold Macmillan was devoted to family members: when Andrew Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire was later appointed he described his uncle's behaviour as "the greatest act of nepotism ever".

Many ministers found Harold Macmillan to be more decisive and brisk than either Churchill or Eden had been.

Harold Macmillan frequently made allusions to history, literature and the classics at cabinet meetings, giving him a reputation as being both learned and entertaining, though many ministers found his manner too authoritarian.

Harold Macmillan had no "inner cabinet", and instead maintained one-on-one relationships with a few senior ministers such as Rab Butler who usually served as acting prime minister when Harold Macmillan was on one of his frequent visits abroad.

Selwyn Lloyd described Harold Macmillan as treating most of his ministers like "junior officers in a unit he commanded".

Harold Macmillan was especially close to his three private secretaries, Tom Bligh, Freddie Bishop and Philip de Zulueta, who were his favourite advisers.

Many cabinet ministers often complained that Harold Macmillan took the advice of his private secretaries more seriously than he did their own.

Harold Macmillan was nicknamed "Supermac" in 1958 by the cartoonist Victor Weisz, who intended to suggest that Macmillan was trying set himself up as a "Superman" figure.

Harold Macmillan bore no grudge against Thorneycroft and brought him and Powell, of whom he was more wary, back into the government in 1960.

Political pressure mounted on the Government, and Harold Macmillan agreed to the 1957 Bank Rate Tribunal.

Harold Macmillan worked to narrow the post-Suez Crisis rift with the United States, where his wartime friendship with Eisenhower was key; the two had a productive conference in Bermuda as early as March 1957.

Harold Macmillan believed that one way to encourage such co-operation would be for the United Kingdom to speed up the development of its own hydrogen bomb, which was successfully tested on 8 November 1957.

Harold Macmillan's decision led to increased demands on the Windscale and Calder Hall nuclear plants to produce plutonium for military purposes.

Concerned that public confidence in the nuclear programme might be shaken and that technical information might be misused by opponents of defence co-operation in the US Congress, Harold Macmillan withheld all but the summary of a report into the fire prepared for the Atomic Energy Authority by Sir William Penney, director of the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment.

On 25 March 1957, Harold Macmillan acceded to Eisenhower's request to base 60 Thor IRBMs in England under joint control to replace the nuclear bombers of the Strategic Air Command, which had been stationed under joint control since 1948 and were approaching obsolescence.

The "revolutionary" change that Harold Macmillan sought was a more equal Anglo-American partnership as he used the Sputnik crisis to press Eisenhower to in turn press Congress to repeal the 1946 MacMahon Act, which forbade the United States to share nuclear technology with foreign governments, a goal accomplished by the end of 1957.

Subsequently, Harold Macmillan was to learn that neither Eisenhower nor Kennedy shared the assumption that he applied to the "Declaration of Interdependence" that the American president and the British Prime Minister had equal power over the decisions of war and peace.

Harold Macmillan believed that the American policies towards the Soviet Union were too rigid and confrontational, and favoured a policy of detente with the aim of relaxing Cold War tensions.

Harold Macmillan led the Conservatives to victory in the 1959 general election, increasing his party's majority from 60 to 100 seats.

Harold Macmillan feared for his own position and later claimed to Lloyd that Butler, who sat for a rural East Anglian seat likely to suffer from EC agricultural protectionism, had been planning to split the party over EC entry.

Harold Macmillan was openly criticised by his predecessor Lord Avon, an almost unprecedented act.

Harold Macmillan supported the creation of the National Economic Development Council, which was announced in the summer of 1961 and first met in 1962.

Harold Macmillan planned an important role in setting up a four power summit in Paris to discuss the Berlin crisis that was supposed to open in May 1960, but which Khrushchev refused to attend owing to the U-2 incident.

Harold Macmillan pressed Eisenhower to apologise to Khrushchev, which the president refused to do.

Harold Macmillan initially was concerned that the Irish-American Catholic Kennedy might be an Anglophobe, which led Harold Macmillan, who knew of Kennedy's special interest in the Third World, to suggest that Britain and the United States spend more money on aid to the Third World.

Harold Macmillan was scheduled to visit the United States in April 1961, but with the Pathet Lao winning a series of victories in the Laotian civil war, Harold Macmillan was summoned on what he called the "Laos dash" for an emergency summit with Kennedy in Key West on 26 March 1961.

Harold Macmillan was strongly opposed to the idea of sending British troops to fight in Laos, but was afraid of damaging relations with the United States if he did not, making him very apprehensive as he set out for Key West, especially as he had never met Kennedy before.

Harold Macmillan was especially opposed to intervention in Laos as he had been warned by his Chiefs of Staff on 4 January 1961 that if Western troops entered Laos, then China would probably intervene in Laos as Mao Zedong had made it quite clear he would not accept Western forces in any nation that bordered China.

The meeting in Key West was very tense as Harold Macmillan was heard to mutter "He's pushing me hard, but I won't give way".

However, Harold Macmillan did reluctantly agree if the Americans intervened in Laos, then so too would Britain.

Harold Macmillan's second meeting with Kennedy in April 1961 was friendlier and his third meeting in London in June 1961 after Kennedy had been bested by Khrushchev at a summit in Vienna even more so.

Harold Macmillan was supportive throughout the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 and Kennedy consulted him by telephone every day.

About the Congo crisis, Harold Macmillan clashed with Kennedy as he was against having United Nations forces put an end to the secessionist regime of Katanga backed by Belgium and the Western mining companies, which he claimed would destabilise the Central African Federation.

Harold Macmillan told his Foreign Secretary, Lord Home "there is no reason for us to help the Americans with Cuba".

Harold Macmillan was a supporter of the nuclear test ban treaty of 1963, and in the first half of 1963 he had Ormsby-Gore quietly apply pressure on Kennedy to resume the talks in the spring of 1963 when negotiations became stalled.

Harold Macmillan had pressing domestic reasons for the nuclear test ban treaty.

Harold Macmillan believed in the value of nuclear weapons both as a deterrent against the Soviet Union and to maintain Britain's claim to be a great power, but he was worried about the popularity of the CND.

For Harold Macmillan, banning above-ground nuclear tests, which generated film footage of the ominous mushroom clouds raising far above the earth, was the best way to dent the appeal of the CND, and in this the Partial Nuclear Ban Treaty of 1963 was successful.

Harold Macmillan felt that if the costs of holding onto a particular territory outweighed the benefits then it should be dispensed with.

Harold Macmillan embarked on his "Wind of Change" tour of Africa, starting in Ghana on 6 January 1960.

Harold Macmillan made the famous 'wind of change' speech in Cape Town on 3 February 1960.

Harold Macmillan's policy overrode the hostility of white minorities and the Conservative Monday Club.

South Africa left the multiracial Commonwealth in 1961 and Harold Macmillan acquiesced to the dissolution of the Central African Federation by the end of 1963.

Harold Macmillan wanted Britain to retain military bases in the new state of Malaysia to ensure that Britain was a military power in Asia and thus he wanted the new state of Malaysia to have a pro-Western government.

Harold Macmillan especially wanted to keep the British base at Singapore, which he like other prime ministers saw as the linchpin of British power in Asia.

Harold Macmillan detested Sukarno, partly because he had been a Japanese collaborator in World War Two, and partly because of his fondness for elaborate uniforms despite never having personally fought in a war offended the World War I veteran Harold Macmillan, who had a strong contempt for any man who had not seen combat.

Harold Macmillan felt that giving in to Sukarno's demands would be "appeasement" and clashed with Kennedy over the issue.

Harold Macmillan feared the expenses of an all-out war with Indonesia, but felt to give in to Sukarno would damage British prestige, writing on 5 August 1963 that Britain's position in Asia would be "untenable" if Sukarno were to triumph over Britain in the same manner he had over the Dutch in New Guinea.

Harold Macmillan cancelled the Blue Streak ballistic missile in April 1960 over concerns about its vulnerability to a pre-emptive attack, but continued with the development of the air-launched Blue Steel stand-off missile, which was about to enter trials.

When Skybolt was unilaterally cancelled by US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Harold Macmillan negotiated with President Kennedy the purchase of Polaris missiles under the Nassau agreement in December 1962.

Harold Macmillan worked with states outside the European Communities to form the European Free Trade Association, which from 3 May 1960 established a free-trade area.

Harold Macmillan saw the value of rapprochement with the EC, to which his government sought belated entry, but Britain's application was vetoed by French president Charles de Gaulle on 29 January 1963.

Harold Macmillan sensed the British were inevitably closely linked to the Americans.

Harold Macmillan saw the European Communities as a continental arrangement primarily between France and Germany, and felt that if Britain joined, France's role would diminish.

Harold Macmillan was a force in the negotiations leading to the signing of the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty by the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union.

Harold Macmillan sent Lord Hailsham to negotiate the Test Ban Treaty, a sign that he was grooming him as a potential successor.

Thorpe writes that from January 1963 "Harold Macmillan's strategy lay in ruins", leaving him looking for a "graceful exit".

Harold Macmillan talked the matter over with his son Maurice and other senior ministers.

Harold Macmillan was almost ready to leave hospital within ten days of the diagnosis and could easily have carried on, in the opinion of his doctor Sir John Richardson.

Enoch Powell claimed that it was wrong of Harold Macmillan to seek to monopolise the advice given to the Queen in this way.

Harold Macmillan was succeeded by Foreign Secretary Alec Douglas-Home in a controversial move; it was alleged that Harold Macmillan had pulled strings and utilised the party's grandees, nicknamed "The Magic Circle", who had slanted their "soundings" of opinion among MPs and Cabinet Ministers to ensure that Butler was not chosen.

Harold Macmillan finally resigned, receiving the Queen from his hospital bed, on 18 October 1963, after nearly seven years as prime minister.

Harold Macmillan felt privately that he was being hounded from office by a backbench minority:.

Harold Macmillan had been elected Chancellor of the University of Oxford in 1960, in a campaign masterminded by Hugh Trevor-Roper, and held this office for the rest of his life, frequently presiding over college events, making speeches and tirelessly raising funds.

In retirement Harold Macmillan took up the chairmanship of his family's publishing house, Harold Macmillan Publishers, from 1964 to 1974.

Harold Macmillan's biographer acknowledges that his memoirs were considered "heavy going".

Harold Macmillan burned his diary for the climax of the Suez Affair, supposedly at Eden's request, although in Campbell's view more likely to protect his own reputation.

Harold Macmillan became president of the Carlton Club in 1977 and would often stay at the club when he had to stay in London overnight.

Harold Macmillan was a member of Buck's, Pratt's, the Turf Club and Beefsteak Club.

Harold Macmillan still travelled widely, visiting China in October 1979, where he held talks with senior Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping.

Harold Macmillan found himself drawn more actively into politics after Margaret Thatcher became Conservative leader in February 1975.

Harold Macmillan was one of several people who advised Thatcher to set up a small War Cabinet to manage the Falklands War.

Harold Macmillan had already received advice to exclude the Treasury from Frank Cooper, not least because of Macmillan's own behaviour, as Chancellor, in demanding a halt to the Suez operation.

Harold Macmillan later recalled: 'I never regretted following Harold Macmillan's advice.

Harold Macmillan is the last non-royal recipient of a hereditary peerage.

Harold Macmillan took the title from his former parliamentary seat on the edge of the Durham coalfields, and in his maiden speech in the House of Lords he criticised Thatcher's handling of the coal miners' strike and her characterisation of striking miners as "the enemy within".

Harold Macmillan received an unprecedented standing ovation for his oration, which included the words:.

Harold Macmillan noted that the decision represented a break with tradition, and predicted that the snub would rebound on the university.

Harold Macmillan is widely supposed to have likened Thatcher's policy of privatisation to "selling the family silver".

Harold Macmillan's speech was much commented on, and a few days later he made a speech in the House of Lords, referring to it:.

Harold Macmillan had often play-acted being an old man long before real old age set in.

Nigel Fisher tells an anecdote of how Harold Macmillan initially greeted him to his house leaning on a stick, but later walked and climbed steps perfectly well, twice acting lame again and fetching his stick when he remembered his "act".

Harold Macmillan was "unique in the affection of the British people".

Harold Macmillan was buried beside his wife and next to his parents and his son Maurice, who had died in 1984.

Thatcher said: "In his retirement Harold Macmillan occupied a unique place in the nation's affections", while Labour leader Neil Kinnock struck a more critical note:.

Harold Macmillan was, of course, not solely or even pre-eminently responsible for that.

Harold Macmillan was an elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1962.

Labour leader Harold Macmillan Wilson wrote that his "role as a poseur was itself a pose".

Historian John Vincent explores the image Harold Macmillan crafted of himself for his colleagues and constituents:.

Harold Macmillan presented himself as a patrician, as the last Edwardian, as a Whig, as a romantic Tory, as intellectual, as a man shaped by the comradeship of the trenches and by the slump of the 1930s, as a shrewd man of business of bourgeois Scottish stock, and as a venerable elder statesman at home with modern youth.

Alistair Horne, his official biographer, concedes that after his re-election in 1959 Harold Macmillan's premiership suffered a series of major setbacks.

However, he argues that Harold Macmillan is remembered as having been "a rather seedy conjuror", famous for Premium Bonds, Beeching's cuts to the railways, and the Profumo Scandal.

Harold Macmillan is best remembered for the "affluent society", which he inherited rather than created in the late 1950s, but chancellors came and went and by the early 1960s economic policy was "nothing short of a shambles", while his achievements in foreign policy made little difference to the lives of the public.

Richard Lamb argues that Harold Macmillan was "by far the best of Britain's postwar Prime Ministers, and his administration performed better than any of their successors".

Note: In a radical reshuffle dubbed "The Night of the Long Knives", Harold Macmillan sacked a third of his Cabinet.