1.

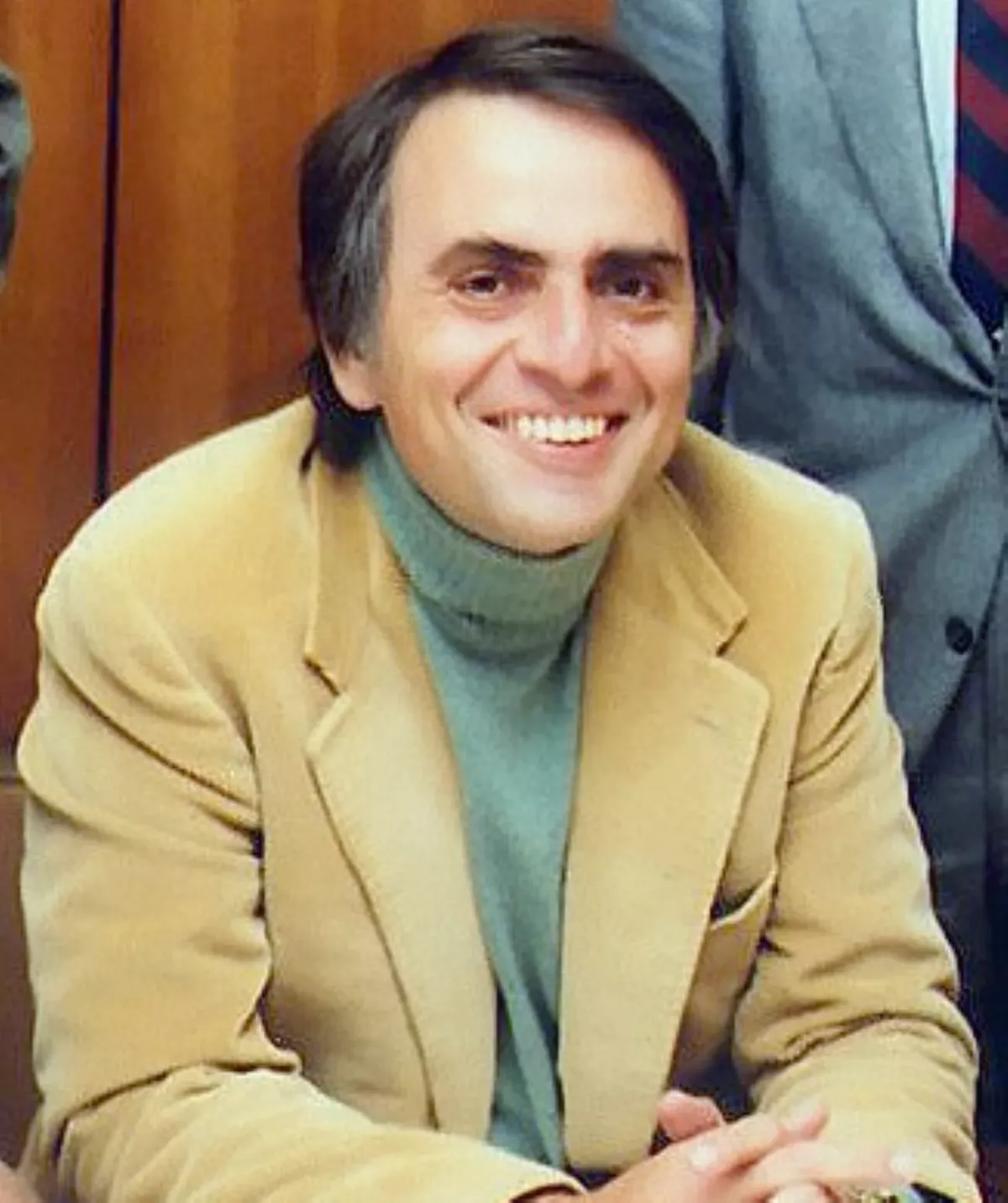

1. Carl Edward Sagan was an American astronomer, planetary scientist and science communicator.

1.

1. Carl Edward Sagan was an American astronomer, planetary scientist and science communicator.

Carl Sagan's best known scientific contribution is his research on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by exposure to light.

Carl Sagan assembled the first physical messages sent into space, the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record, which were universal messages that could potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find them.

Carl Sagan argued in favor of the hypothesis, which has since been accepted, that the high surface temperatures of Venus are the result of the greenhouse effect.

Carl Sagan published more than 600 scientific papers and articles and was author, co-author or editor of more than 20 books.

Carl Sagan wrote many popular science books, such as The Dragons of Eden, Broca's Brain, Pale Blue Dot and The Demon-Haunted World.

Carl Sagan co-wrote and narrated the award-winning 1980 television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which became the most widely watched series in the history of American public television: Cosmos has been seen by at least 500 million people in 60 countries.

Carl Sagan wrote a science-fiction novel, published in 1985, called Contact, which became the basis for the 1997 film Contact.

Carl Sagan's papers, comprising 595,000 items, are archived in the Library of Congress.

Carl Sagan was a popular public advocate of skeptical scientific inquiry and the scientific method; he pioneered the field of exobiology and promoted the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

Carl Sagan spent most of his career as a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, where he directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies.

Carl Edward Sagan was born on November 9,1934, in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of New York City's Brooklyn borough.

Carl Sagan's mother, Rachel Molly Gruber, was a housewife from New York City; his father, Samuel Sagan, was a Ukrainian-born garment worker who had emigrated from Kamianets-Podilskyi.

Carl Sagan later described his family as Reform Jews, one of the more liberal of Judaism's four main branches.

Later, during his career, Carl Sagan would draw on his childhood memories to illustrate scientific points, as he did in his book Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.

Carl Sagan later described his vivid memories of several exhibits there.

Carl Sagan saw an exhibit of the then-nascent medium known as television.

Carl Sagan saw one of the fair's most publicized events: the burial at Flushing Meadows of a time capsule, which contained mementos from the 1930s to be recovered by Earth's descendants in a future millennium.

Carl Sagan recalled taking his first trips to the public library alone, at age five, when his mother got him a library card.

Carl Sagan's parents nurtured his growing interest in science, buying him chemistry sets and reading matter.

That same year, mass hysteria developed about the possibility that extraterrestrial visitors had arrived in flying saucers, and the young Carl Sagan joined in the speculation that the flying "discs" people reported seeing in the sky might be alien spaceships.

Carl Sagan was a straight-A student but was bored because his classes did not challenge him and his teachers did not inspire him.

Carl Sagan became president of the school's chemistry club, and set up his own laboratory at home.

Carl Sagan attended the University of Chicago because, despite his excellent high school grades, it was one of the very few colleges he had applied to that would consider accepting a 16-year-old.

Carl Sagan went on to do graduate work at the University of Chicago, earning a Master of Science in physics in 1956 and a Doctor of Philosophy in astronomy and astrophysics in 1960.

The title of Carl Sagan's dissertation reflected interests he had in common with Kuiper, who had been president of the International Astronomical Union's commission on "Physical Studies of Planets and Satellites" throughout the 1950s.

Carl Sagan had a Top Secret clearance at the Air Force and a Secret clearance with NASA.

In 1999, an article published in the journal Nature revealed that Carl Sagan had included the classified titles of two Project A119 papers in his 1959 application for a scholarship to University of California, Berkeley.

From 1960 to 1962, Carl Sagan was a Miller Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.

Carl Sagan instead asked to be made an assistant professor, and eventually Whipple and Menzel were able to convince Harvard to offer Carl Sagan the assistant professor position he requested.

Carl Sagan lectured, performed research, and advised graduate students at the institution from 1963 until 1968, as well as working at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, located in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Carl Sagan later indicated that the decision was very unexpected.

Long before the ill-fated tenure process, Cornell University astronomer Thomas Gold had courted Carl Sagan to move to Ithaca, New York, and join the recently hired astronomer Frank Drake among the faculty at Cornell.

Unlike Harvard, the smaller and more laid-back astronomy department at Cornell welcomed Carl Sagan's growing celebrity status.

Carl Sagan was associated with the US space program from its inception.

Carl Sagan contributed to many of the robotic spacecraft missions that explored the Solar System, arranging experiments on many of the expeditions.

Carl Sagan continued to refine his designs; the most elaborate message he helped to develop and assemble was the Voyager Golden Record, which was sent out with the Voyager space probes in 1977.

Carl Sagan often challenged the decisions to fund the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station at the expense of further robotic missions.

Carl Sagan's contributions were central to the discovery of the high surface temperatures of the planet Venus.

Carl Sagan was among the first to hypothesize that Saturn's moon Titan might possess oceans of liquid compounds on its surface and that Jupiter's moon Europa might possess subsurface oceans of water.

Carl Sagan further contributed insights regarding the atmospheres of Venus and Jupiter, as well as seasonal changes on Mars.

Carl Sagan perceived global warming as a growing, man-made danger and likened it to the natural development of Venus into a hot, life-hostile planet through a kind of runaway greenhouse effect.

Carl Sagan testified to the US Congress in 1985 that the greenhouse effect would change the Earth's climate system.

Carl Sagan studied the observed color variations on Mars' surface and concluded that they were not seasonal or vegetational changes as most believed, but shifts in surface dust caused by windstorms.

Carl Sagan is known for his research on the possibilities of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation.

In 1980, Carl Sagan co-wrote and narrated the award-winning 13-part PBS television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which became the most widely watched series in the history of American public television until 1990.

The book, Cosmos, written by Carl Sagan, was published to accompany the series.

Carl Sagan's number is the number of stars in the observable universe.

Carl Sagan delivered the 1977 series of Royal Institution Christmas Lectures in London.

Carl Sagan was a proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life.

Carl Sagan urged the scientific community to listen with radio telescopes for signals from potential intelligent extraterrestrial life-forms.

Carl Sagan was so persuasive that by 1982 he was able to get a petition advocating SETI published in the journal Science, signed by 70 scientists, including seven Nobel Prize winners.

Carl Sagan helped Frank Drake write the Arecibo message, a radio message beamed into space from the Arecibo radio telescope on November 16,1974, aimed at informing potential extraterrestrials about Earth.

Carl Sagan was chief technology officer of the professional planetary research journal Icarus for 12 years.

Carl Sagan co-founded The Planetary Society and was a member of the SETI Institute Board of Trustees.

Carl Sagan served as Chairman of the Division for Planetary Science of the American Astronomical Society, as President of the Planetology Section of the American Geophysical Union, and as Chairman of the Astronomy Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

At the height of the Cold War, Carl Sagan became involved in nuclear disarmament efforts by promoting hypotheses on the effects of nuclear war, when Paul Crutzen's "Twilight at Noon" concept suggested that a substantial nuclear exchange could trigger a nuclear twilight and upset the delicate balance of life on Earth by cooling the surface.

Carl Sagan received a great deal of skepticism and disdain for the use of media to disseminate a very uncertain hypothesis.

Carl Sagan wrote the best-selling science fiction novel Contact in 1985, based on a film treatment he wrote with his wife, Ann Druyan, in 1979, but he did not live to see the book's 1997 motion-picture adaptation, which starred Jodie Foster and won the 1998 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.

Carl Sagan wrote a sequel to Cosmos, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, which was selected as a notable book of 1995 by The New York Times.

Carl Sagan appeared on PBS's Charlie Rose program in January 1995.

Carl Sagan wrote the introduction for Stephen Hawking's bestseller A Brief History of Time.

Carl Sagan was known for his popularization of science, his efforts to increase scientific understanding among the general public, and his positions in favor of scientific skepticism and against pseudoscience, such as his debunking of the Betty and Barney Hill abduction.

Carl Sagan argued that all of the numerous methods proposed to alter the orbit of an asteroid, including the employment of nuclear detonations, created a deflection dilemma: if the ability to deflect an asteroid away from the Earth exists, then one would have the ability to divert a non-threatening object towards Earth, creating an immensely destructive weapon.

Carl Sagan believed that ideas were far more real than the natural world.

Carl Sagan advised the astronomers not to waste their time observing the stars and planets.

Carl Sagan taught contempt for the real world and disdain for the practical application of scientific knowledge.

In 1995, Carl Sagan popularized a set of tools for skeptical thinking called the "baloney detection kit", a phrase first coined by Arthur Felberbaum, a friend of his wife Ann Druyan.

Urey and Carl Sagan were said to have different philosophies of science, according to Davidson.

Carl Sagan was accused of borrowing some ideas of others for his own benefit and countered these claims by explaining that the misappropriation was an unfortunate side effect of his role as a science communicator and explainer, and that he attempted to give proper credit whenever possible.

Carl Sagan believed that the Drake equation, on substitution of reasonable estimates, suggested that a large number of extraterrestrial civilizations would form, but that the lack of evidence of such civilizations highlighted by the Fermi paradox suggests technological civilizations tend to self-destruct.

Hundreds of people in the "Nevada Desert Experience" group were arrested, including Carl Sagan, who was arrested on two separate occasions as he climbed over a chain-link fence at the test site during the underground Operation Charioteer and United States's Musketeer nuclear test series of detonations.

Carl Sagan was a vocal advocate of the controversial notion of testosterone poisoning, arguing in 1992 that human males could become gripped by an "unusually severe [case of] testosterone poisoning" and this could compel them to become genocidal.

Carl Sagan married artist Linda Salzman in 1968 and they had a child together, Nick Carl Sagan, and divorced in 1981.

In 1981, Carl Sagan married author Ann Druyan and they later had two children, Alexandra and Samuel Carl Sagan.

The name was only used internally, but Carl Sagan was concerned that it would become a product endorsement and sent Apple a cease-and-desist letter.

Carl Sagan was acquainted with science fiction fandom through his friendship with Isaac Asimov, and he spoke at the Nebula Awards ceremony in 1969.

Carl Sagan wrote frequently about religion and the relationship between religion and science, expressing his skepticism about the conventional conceptualization of God as a sapient being.

Carl Sagan thought that spirituality should be scientifically informed and that traditional religions should be abandoned and replaced with belief systems that revolve around the scientific method, but the mystery and incompleteness of scientific fields.

In reply to a question in 1996 about his religious beliefs, Carl Sagan said he was agnostic.

Carl Sagan maintained that the idea of a creator God of the Universe was difficult to prove or disprove and that the only conceivable scientific discovery that could challenge it would be an infinitely old universe.

Carl Sagan faced his death with unflagging courage and never sought refuge in illusions.

Late in his life, Carl Sagan's books elaborated on his naturalistic view of the world.

The compilation Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium, published in 1997 after Carl Sagan's death, contains essays written by him, on topics such as his views on abortion, and an essay by his widow, Ann Druyan, about the relationship between his agnostic and freethinking beliefs and his death.

Carl Sagan was the faculty adviser for the Cornell Students for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.

In 1947, the year that inaugurated the "flying saucer" craze, the young Carl Sagan suspected the "discs" might be alien spaceships.

Carl Sagan later had several conversations on the subject in 1964 with Jacques Vallee.

Carl Sagan rejected an extraterrestrial explanation for the phenomenon but felt there were both empirical and pedagogical benefits for examining UFO reports and that the subject was, therefore, a legitimate topic of study.

Carl Sagan again revealed his views on interstellar travel in his 1980 Cosmos series.

In one of his last written works, Carl Sagan argued that the chances of extraterrestrial spacecraft visiting Earth are vanishingly small.

Carl Sagan briefly served as an adviser on Stanley Kubrick's film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Carl Sagan proposed that the film suggest, rather than depict, extraterrestrial superintelligence.

Carl Sagan was buried at Lake View Cemetery in Ithaca, New York.

The 1997 film Contact was based on the only novel Carl Sagan wrote and finished after his death.

In 1997, the Carl Sagan Planet Walk was opened in Ithaca, New York.

The exhibition was created in memory of Carl Sagan, who was an Ithaca resident and Cornell Professor.

Professor Carl Sagan had been a founding member of the museum's advisory board.

Carl Sagan has at least three awards named in his honor:.

In 2023, a movie Voyagers by Sebastian Lelio was announced with Carl Sagan played by Andrew Garfield and with Daisy Edgar-Jones playing Carl Sagan's third wife, Ann Druyan.