1.

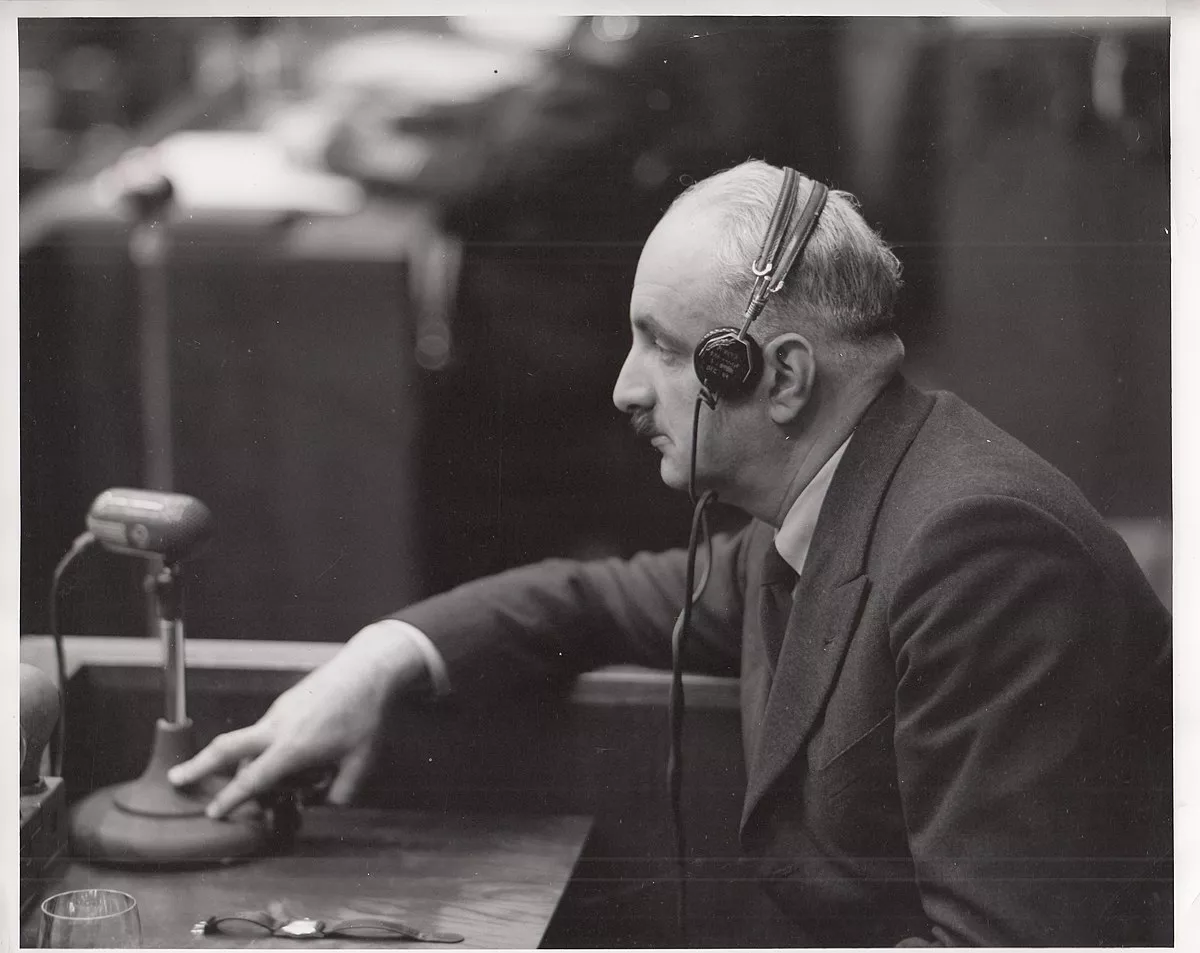

1. Franz Borkenau is known as one of the pioneers of the totalitarianism theory.

1.

1. Franz Borkenau is known as one of the pioneers of the totalitarianism theory.

Franz Borkenau was born in Vienna, the son of Judge Rudolf Pollack and Melanie Furth.

Franz Borkenau's father was born Jewish, but had converted to Roman Catholicism to improve his career prospects while his mother was Protestant.

Vienna was the capital of the vast multicultural and multiethnic Austrian empire that covered much of Eastern Europe, and Franz Borkenau grew up in a cosmopolitan city that was full of various peoples.

Franz Borkenau was still in training at the time that the Austrian empire was defeated and the ancient House of Habsburg was deposed in October 1918.

Franz Borkenau was typical of the Austrian middle class who had enjoyed what the novelist Stefan Zweig called the "golden age of security" before 1914 and found the world that came about after 1918 to be as disorientating as it was disturbing, leading to a search for a new "anchor" ideology to provide certainty in a dangerous and uncertain world.

Franz Borkenau ended up transferring over to the University of Leipzig, where he was awarded a PhD in 1924.

Franz Borkenau was always interested in devising grand theories that could explain everything that had happened in history, and believed that he had found such a theory in Marxism.

In 1921, Franz Borkenau joined the Communist Party of Germany and was active as a Comintern agent until 1929.

From 1925 to 1929, Franz Borkenau worked as a research assistant for Jurgen Kuczynski at the Forschungsstelle fur internationale Politik in Berlin, a think-tank that was sponsored by the German Communist Party.

Franz Borkenau then joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which he remained a member of until 1931 when he resigned.

Franz Borkenau tried to organise socialist resistance against the Dollfuss regime, but upon learning he was wanted by the Austrian police, fled to Paris.

From 1934 to 1935, Franz Borkenau lived in Paris, where he unsuccessfully sought an academic position.

In 1936, Franz Borkenau moved back to London, where he worked as a journalist for a number of left-wing and liberal British newspapers.

Franz Borkenau argued that the political, social and economic crises caused by World War I caused the strongest capitalists to form a "new economic elite".

Franz Borkenau argued that Vladimir Lenin created the first totalitarian dictatorship with all power concentrated into the hands of the state, which was completely unconstrained by any class forces as all previous regimes had been.

Franz Borkenau wrote a response to Touchy's article, which he called full of hysteria and inaccuracies, saying he had not seen the widespread "sexual depravity" that Touchy claimed to have witnessed.

Franz Borkenau wrote against Touchy that women serving in the Worker's Militia did not seem to be causing the sort of social breakdown that Touchy claimed it had, saying the society was being strained by the war, but it was holding up to the challenge.

Franz Borkenau's experience inspired his best-known book, The Spanish Cockpit, which was widely praised and "made Franz Borkenau's name famous throughout the English-speaking world".

In particular, Franz Borkenau made an issue of the Soviet treatment of Manfred Stern who under the alias of General Emilio Kleber had emerged as the most able of the officers leading the International Brigades fighting for the republic.

Franz Borkenau described the Spanish civil war as an aborted revolution, writing that in every revolution it was always the most organised faction that gained the ascendency, leading him to conclude:.

Franz Borkenau argued that the Spanish anarchists were too democratic and too disorganised for their own good as he argued the more disciplined and better-organised Spanish Communists had the advantage.

Franz Borkenau argued that the problem with the Spanish Republican Army was the politics of the Spanish Republic, writing:.

Franz Borkenau felt that the main strength of the Spanish Republic, its dependence upon economic and military support from the Soviet Union, was its main weakness.

Franz Borkenau's book Austria and After was an attack on the Nazi Anschluss.

Franz Borkenau wrote that the main dividing line in Austrian politics was the division between the urban areas of Austria, especially Vienna, that voted for the Austrian Social Democratic Party, and the rural areas of Austria that favored a conservative Catholicism.

Franz Borkenau wrote: "It is doubtful whatever the clergy, who had defended the War to the end, would have easily kept the alliance of the peasants after it, had there not existed the socialist bogy".

Franz Borkenau argued that support of the trade unions had ensured that the Austrian working class voted solidly for the Social Democrats, who came to dominate Vienna so much that it was popularly known as "Red Vienna".

Franz Borkenau wrote that after the clashes of 15 July 1927, Austrian politics were in a state of latent civil war as there was no possibility of co-operation again.

Franz Borkenau concluded that the victory of the conservatives in the 1934 civil war was ironically the source of their downfall.

In 1939, Franz Borkenau published The New German Empire, where he warned that Adolf Hitler was intent upon world conquest.

In particular, Franz Borkenau advised against the idea, popular in Britain in the 1930s, that the British government should return former German colonies in Africa in exchange for a German promise to respect the borders of Europe.

Franz Borkenau argued that the Germans would never honour such a promise, returning the former German colonies would only provide a new field of conflict, and Hitler's determination to overthrow the Treaty of Versailles was "an almost insignificant incident on the road to unlimited expansion".

Franz Borkenau claimed that the German propaganda campaign for the former African colonies was a "stepping stone to something else", the "acquisition of a wider colonial area" for Germany.

Franz Borkenau asserted that the propaganda campaign for the return of the former German colonies in Africa was intended for their strategic value in helping to prepare the ground for a war against Britain and France, rather than the economic value, which Borkenau noted was very small.

Franz Borkenau argued that the main German target in Africa was South Africa.

Franz Borkenau contended that if Britain returned the former German colonies to the Reich, the Germans would arouse the anti-British elements within the Afrikaner population.

Franz Borkenau argued that the Nazi regime was revolutionary, but not in a way that conformed to popular ideas of "current revolutions" because with the exception of the German Jews, the Nazi regime had "respected property rights".

Franz Borkenau argued against the popular idea in Britain that the Nazi regime would eventually settle down into a type of "normalcy" as a profound misreading of the Third Reich.

Franz Borkenau argued that the Nazi regime was driven by relentless dynamism, which even Hitler did not fully control, as he argued that the Nazi regime was not so much a one-party state as a new religion consumed in a "quasi-mystical fanaticism".

In Franz Borkenau's reading, the Nazi ideology was fundamentally negative, as the regime defined itself more in terms of what it was against rather than what it was for, thus requiring a policy of endless aggression.

Franz Borkenau wrote that "the complete disintegration of the old economic structures and the old spiritual values in Germany" made the National Socialist regime sui generis.

However, Franz Borkenau's work differed from the functionalists in that he maintained that the Nazi regime was a well-organized totalitarian dictatorship.

In 1939, Franz Borkenau wrote: "There is little doubt that within a few years the fate of the Jews in eastern Europe will resemble that of the Armenians in Turkey".

In 1940, Franz Borkenau was interned by the British government as an "enemy alien" and deported to an internment camp in Australia.

Franz Borkenau concluded that the wartime expansion of the powers of the state would mean some sort of socialism was the solution to the world's problems, writing that "a planned economy, if once established, should never abolish individual means of ownership".

Franz Borkenau argued that reconstruction of the world economy was not compatible "with a programme of class struggle", leading him to write that the best party to lead Britain after the war ended was the Labour Party.

Franz Borkenau rejected Communism, and instead urged an alliance of the Labour Party with the left wing of the Democratic Party in the United States.

For Britain, Franz Borkenau urged a gradualist transition from capitalism to socialism, writing that "precisely through the gradual growth of state intervention" as preached by the Labour Party was the best way forward.

In 1947, Franz Borkenau returned to Germany to work as a professor at the University of Marburg.

In June 1950, Borkenau attended the conference in Berlin together with other anti-Communist intellectuals such as Hugh Trevor-Roper, Ignazio Silone, Raymond Aron, Arthur Koestler, Sidney Hook and Melvin J Lasky that resulted in the initiation of the Congress for Cultural Freedom.

At the conference, Franz Borkenau delivered the theme speech, for which he spoke of the "meaninglessness" of the conflict between capitalism and socialism in a time of "ebbing revolution", and the only conflict that mattered in the world was the one between Communism and democracy.

Left-wing intellectuals such as Cedric Belfrage, noting that Hitler often denounced Communism in Berlin, like Franz Borkenau did, would compare his speech to the Nuremberg rallies and accused Franz Borkenau of being a sort of neo-Nazi.

Franz Borkenau was very active in the Congress, and was often criticized by Marxist intellectuals such as Isaac Deutscher for his anti-Communism.

Franz Borkenau claimed that Deutscher was engaging in an apologia for Stalin since, in his opinion, there was nothing that supported Stalin's version of events about the alleged coup plot of 1937.

Franz Borkenau argued that despite the appearance of unity, there were power struggles within the Soviet elite.

Franz Borkenau's techniques were a minute analysis of official Soviet statements and the relative placement of various officials at the Kremlin on festive occasions to determine which Soviet official enjoyed Stalin's favour and which official did not.

In 1954, Franz Borkenau wrote that he made that prediction on the basis of a resolution of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany on the "lessons of the Slansky case".

Franz Borkenau argued that German literature tended to celebrate individual "superman" heroes who achieved superhuman feats in battle while French literature did not.

Franz Borkenau used as an example the French epic poem Chanson de Roland, where the hero Roland, against the advice of his best friend Oliver, chooses not ask for the readily available help of Charlemagne's army against a Muslim army invading from the Iberian Peninsula.

Franz Borkenau noted that the result of Roland's vainglorious desire is his own death and the destruction of his own army, which was very different from how medieval German poets would have handled the story.

Franz Borkenau became increasingly active as a freelance author living in Paris, Rome and Zurich, where he died suddenly of heart failure in 1957.