1.

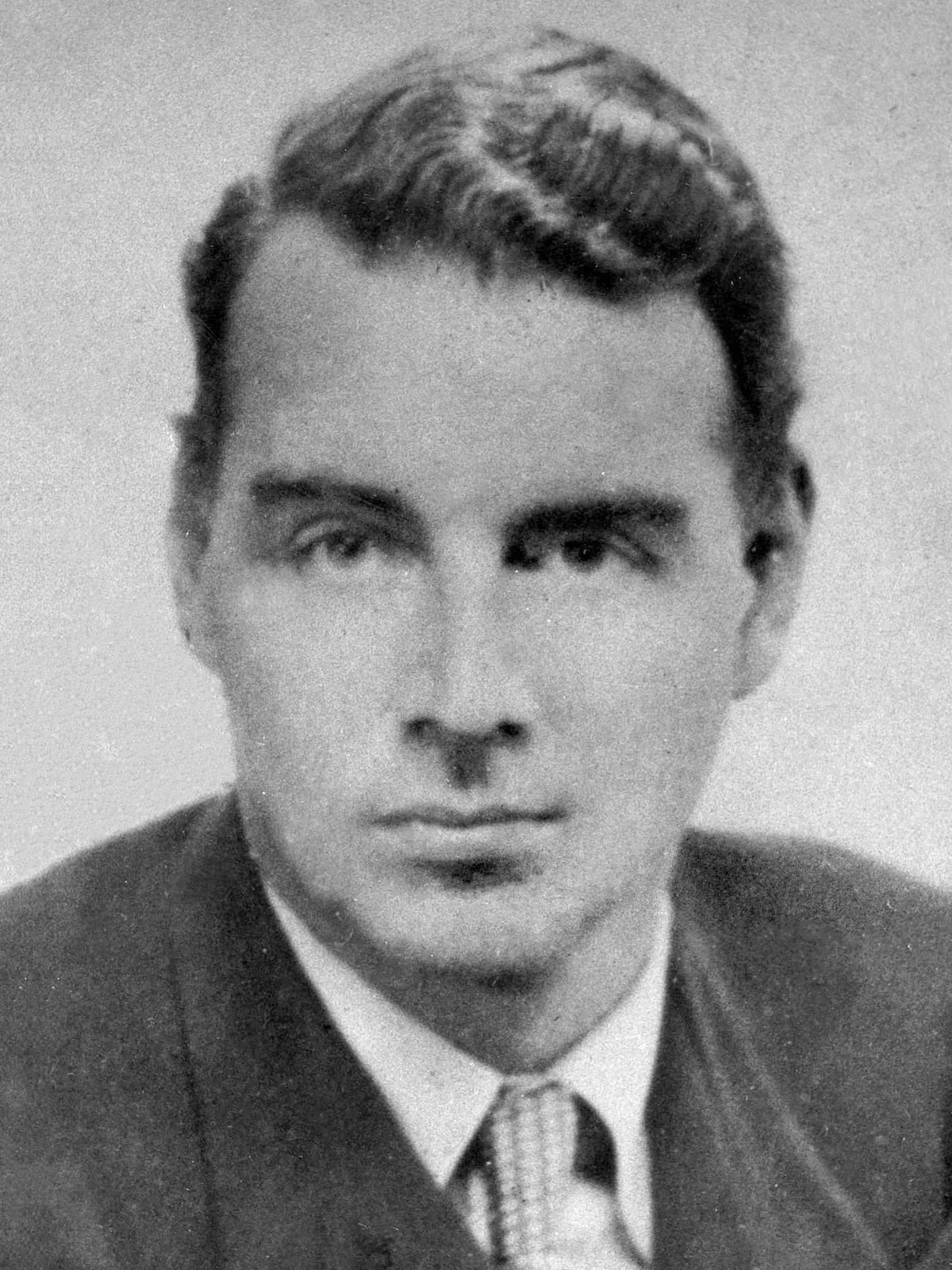

1. Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess was a British diplomat and Soviet double agent, and a member of the Cambridge Five spy ring that operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era.

1.

1. Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess was a British diplomat and Soviet double agent, and a member of the Cambridge Five spy ring that operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era.

Guy Burgess was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1935, on the recommendation of the future double agent Harold "Kim" Philby.

At the Foreign Office, Guy Burgess acted as a confidential secretary to Hector McNeil, deputy to Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin.

Guy Burgess's whereabouts were unknown in the West until 1956, when he appeared with Maclean at a brief press conference in Moscow, claiming that his motive had been to improve Soviet-West relations.

Guy Burgess never left the Soviet Union; he was often visited by friends and journalists from Britain, most of whom reported a lonely and empty existence.

Guy Burgess remained unrepentant to the end of his life, rejecting the notion that his earlier activities represented treason.

Guy Burgess was well provided for materially, but as a result of his lifestyle his health deteriorated, and he died in 1963.

Guy Burgess's life has frequently been fictionalised, and dramatised in productions for screen and stage, notably in the 1981 Julian Mitchell play Another Country and its 1984 film adaptation.

Guy Burgess was responsible for revealing to the Soviets the existence of the Information Research Department, a secret wing of the Foreign Office which dealt with Cold War and pro-colonial propaganda, for which Guy Burgess worked until swiftly ousted after being accused of coming into work drunk.

Later generations created a military tradition; Guy Burgess's grandfather, Henry Miles Guy Burgess, was an officer in the Royal Artillery whose main service was in the Middle East.

Guy Burgess's youngest son, Malcolm Kingsford de Moncy Burgess, was born in Aden in 1881, the third forename being a nod to his Huguenot ancestry.

Guy Burgess did well there; his grades were consistently good and he played for the school's association football team.

Guy Burgess was marked by the college authorities as "excellent officer material", but an eye test in 1927 exposed a deficiency that precluded a career in the navy's executive branch.

Generally, Guy Burgess was remembered as amusingly flamboyant, and something of an oddity with his professed left-wing social and political opinions.

Guy Burgess arrived in Cambridge in October 1930 and quickly involved himself in many aspects of student life.

Guy Burgess was not universally liked; one contemporary described him as "a conceited unreliable shit", although others found him amusing and good company.

In June 1931 Guy Burgess designed the stage sets for a student production of Bernard Shaw's play Captain Brassbound's Conversion, with Michael Redgrave in the leading role.

Under Guest's influence, Guy Burgess began studying the works of Marx and Lenin.

In 1932 Guy Burgess obtained first-class honours in Part I of the history Tripos and was expected to graduate with similar honours in Part II the following year.

Guy Burgess's chosen research area was "Bourgeois Revolution in Seventeenth-Century England", but much of his time was devoted to political activism.

Alongside Guy Burgess was Donald Maclean, a languages student from Trinity Hall and an active CUSS member.

Rees had planned to visit the Soviet Union with a fellow don in the 1934 summer vacation, but was unable to go; Guy Burgess took his place.

On his return, Guy Burgess had little to report, beyond commenting on the "appalling" housing conditions while praising the country's lack of unemployment.

When Guy Burgess returned to Cambridge in October 1934, his prospects of a college fellowship and an academic career were fast receding.

Guy Burgess had abandoned his research after discovering that the same ground was covered in a new book by Basil Willey.

Guy Burgess began an alternative study of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, but his time was largely preoccupied with politics.

Guy Burgess recommended Burgess, although with some reservations on account of the latter's erratic personality.

Guy Burgess then persuaded Blunt that he could best fight fascism by working for the Soviets.

Finally recognising that he had no future career at Cambridge, Guy Burgess left in April 1935 without completing his degree.

Guy Burgess then looked for suitable work, applying without success for positions with the Conservative Research Department and Conservative Central Office.

Guy Burgess sought a teaching job at Eton, but was rejected when a request for information from his former Cambridge tutor received the reply: "I would very much prefer not to answer your letter".

Late in 1935, Guy Burgess accepted a temporary post as personal assistant to John Macnamara, the recently elected Conservative Member of Parliament for Chelmsford.

Macnamara was on the right of his party; he and Guy Burgess joined the Anglo-German Fellowship, which promoted friendship with Nazi Germany.

In July 1936, having twice previously applied unsuccessfully for posts at the BBC, Guy Burgess was appointed as an assistant producer in the corporation's Talks Department.

Guy Burgess sought out Winston Churchill, then a powerful backbench opponent of the government's appeasement policy.

On 1 October 1938, during the Munich crisis, Guy Burgess, who had met Churchill socially, went to the latter's home at Chartwell to persuade him to reconsider his decision to withdraw from a projected talks series on Mediterranean countries.

Guy Burgess was trusted sufficiently to be used as a back channel of communication between Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his French counterpart, Edouard Daladier, during the period leading to the 1938 Munich summit.

Guy Burgess acted as Section D's representative on the Joint Broadcasting Committee, a body set up by the Foreign Office to liaise with the BBC over the transmission of anti-Hitler broadcasts to Germany.

Guy Burgess informed them that the British government saw no need for a pact with the Soviets since they believed Britain alone could defeat the Germans without assistance.

Philby later was sceptical of the value of such training, since neither he nor Guy Burgess had any idea of the tasks these agents would be expected to perform behind the lines in German-occupied Europe.

In mid-January 1941 Guy Burgess rejoined the BBC Talks Department, while continuing to carry out freelance intelligence work, both for MI6 and its domestic intelligence counterpart MI5, which he had joined in a supernumerary capacity in 1940.

Guy Burgess turned again to Blunt, and to his old Cambridge friend Jim Lees, and in 1942 arranged a broadcast by Ernst Henri, a Soviet agent masquerading as a journalist.

In October 1941 Guy Burgess took charge of the flagship political programme The Week in Westminster, which gave him almost unlimited access to Parliament.

Guy Burgess sought to maintain a political balance; his fellow Etonian Quintin Hogg, a future Conservative Lord Chancellor, was a regular broadcaster, as, from the opposite social and political spectrum, was Hector McNeil, a former journalist who became a Labour MP in 1941 and served as a parliamentary private secretary in the Churchill war ministry.

Guy Burgess had lived in a Chester Square flat since 1935.

Guy Burgess constantly sought to further infiltrate higher positions of power, so when he was offered a job in the news department of the Foreign Office in June 1944, he accepted it.

Guy Burgess passed information relating to the postwar futures of Germany and Poland, and contingency plans for "Operation Unthinkable", which anticipated a future war with the Soviet Union.

Guy Burgess's working methods were characteristically disorganised, and his tongue was loose; according to his colleague Osbert Lancaster, "[w]hen in his cups he made no bones about working for the Russians".

Guy Burgess had maintained contact with McNeil who, following Labour's victory in the 1945 general election, became Minister of State at the Foreign Office, effectively serving as a deputy to Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin.

Early in 1948, Guy Burgess was seconded to the Foreign Office's newly created Information Research Department, set up to counteract Soviet propaganda.

Guy Burgess was quickly sent back to McNeil's office, and in March 1948 accompanied McNeil and Bevin to Brussels for the signing of the Treaty of Brussels, which eventually led to the establishment of the Western European Union and NATO.

Guy Burgess remained with McNeil until October 1948, when he was posted to the Far East.

Guy Burgess was assigned to the China desk at a point when the Chinese Civil War was nearing its climax, a communist victory imminent.

Guy Burgess was a forceful advocate for recognition and may have influenced Britain's decision to recognise Communist China in 1949.

Back in London, Guy Burgess was reprimanded, but somehow retained the confidence of his superiors, so that his next posting, in July 1950, was to Washington, as second secretary in what Purvis and Hulbert describe as "one of the UK's highest profile embassies, the creme de la creme of diplomatic postings".

Guy Burgess soon reverted to his erratic and intemperate habits, causing regular embarrassment in British diplomatic circles.

The episode passed without trouble; the two, both Etonians, got on well, and Guy Burgess received a warm letter of thanks from Eden "for all your kindness".

Guy Burgess considered leaving the diplomatic service altogether, and began sounding out his Eton friend Michael Berry about a journalistic post on The Daily Telegraph.

Guy Burgess was thus given the task, on reaching London, of organising Maclean's defection to the Soviet Union.

Guy Burgess showed little urgency in proceeding with the matter, finding time to pursue his personal affairs and attend an Apostles dinner in Cambridge.

Guy Burgess met with Maclean several times; according to Burgess's 1956 account to Driberg, the question of defection to Moscow was not raised until their third meeting, when Maclean said he was going and requested Burgess's help.

Guy Burgess had previously promised Philby that he would not go with Maclean, since a double defection would put Philby's own position in serious jeopardy.

Guy Burgess told Driberg that he had agreed to accompany Maclean because he was leaving the Foreign Office anyway, "and I probably couldn't stick the job at the Daily Telegraph".

Guy Burgess hired a saloon car, and that evening drove to Maclean's house at Tatsfield, Surrey, where he introduced himself to Maclean's wife Melinda as "Roger Styles".

Since Guy Burgess never went away without telling his mother, his absence caused some anxiety in his circle.

Disquiet increased when officials realised that Guy Burgess, too, was missing; the discovery of the abandoned car, hired in Guy Burgess's name, together with Melinda Maclean's revelations about "Roger Styles", confirmed that both had fled.

Just before Christmas 1953, Guy Burgess's mother received a letter from her son, postmarked in South London.

Evidence against Guy Burgess was not significant at the time of his defection but became apparent with further investigation.

Guy Burgess brought with him papers indicating that Burgess and Maclean had been Soviet agents since their Cambridge days, that the MGB had masterminded their escape, and that they were alive and well in the Soviet Union.

Guy Burgess expected to be permitted to return to England, where he thought he could brazen out his MI5 interrogation.

Guy Burgess found the Soviets intolerant of homosexuality, although eventually he was allowed to retain a Russian romantic partner, Tolya Chisekov.

Guy Burgess stayed a month, mainly in the holiday resort of Sochi.

On his return, Driberg wrote a book in which Guy Burgess was portrayed relatively sympathetically.

Some assumed that the content had been vetted by the KGB as a propaganda exercise; others thought its purpose was to trap Guy Burgess into revealing information that could lead to his prosecution, should he ever return to Britain.

Sir Michael Redgrave arrived with the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre Company in February 1959; this visit led to Guy Burgess' meeting with the actress Coral Browne, a friendship that became the subject of Alan Bennett's play An Englishman Abroad.

When Prime Minister Harold Macmillan visited Moscow in 1959, Guy Burgess offered his expertise to the visiting party.

Guy Burgess's offer was declined, but he used this opportunity to lobby officials for permission to visit Britain where, he said, his mother was sick.

Guy Burgess suffered from increasing ill health, largely due to a lifestyle based on poor food and excessive alcohol.

Guy Burgess died on 30 August 1963, of arteriosclerosis and acute liver failure.

Guy Burgess was cremated five days later; Nigel Burgess represented the family, and Maclean delivered a eulogy describing his co-defector as "a gifted and courageous man who devoted his life to the cause of a better world".

Guy Burgess never deviated from the ideological justification that he gave on his reappearance in 1956; he believed that the stark choice to be made in the twentieth century was between America and the Soviet Union.

Noel Annan, in his account of British intellectual life between the world wars, states that Guy Burgess "was a true Stalinist who hated liberals more than imperialists" and "simply believed that Britain's future lay with Russia not America".

Guy Burgess insisted there was no viable case against him in England, but would not visit there, since he might be prevented from returning to Moscow where he wished to live "because I am a socialist and this is a socialist country".

Guy Burgess's life, says Lownie, can only be explained by an understanding of "the intellectual maelstrom of the 1930s, particularly amongst the young and impressionable".

Holzman stresses the high price of Guy Burgess's political continuing commitment, which "cost him everything else he valued: the possibility of fulfilling intimate relationships, the social life that revolved around the BBC, Fleet Street and Whitehall, even the chance to be with his mother as she lay dying".

Stage and screen works include Bennett's An Englishman Abroad, Granada TV's 1987 drama Philby, Burgess and Maclean, the 2003 BBC miniseries Cambridge Spies, and John Morrison's 2011 stage play A Morning with Guy Burgess, set in the last months of his life and examining themes of loyalty and betrayal.

Two biographies of Guy Burgess were published in 2016 after the release of secret files to the National Archives.