1.

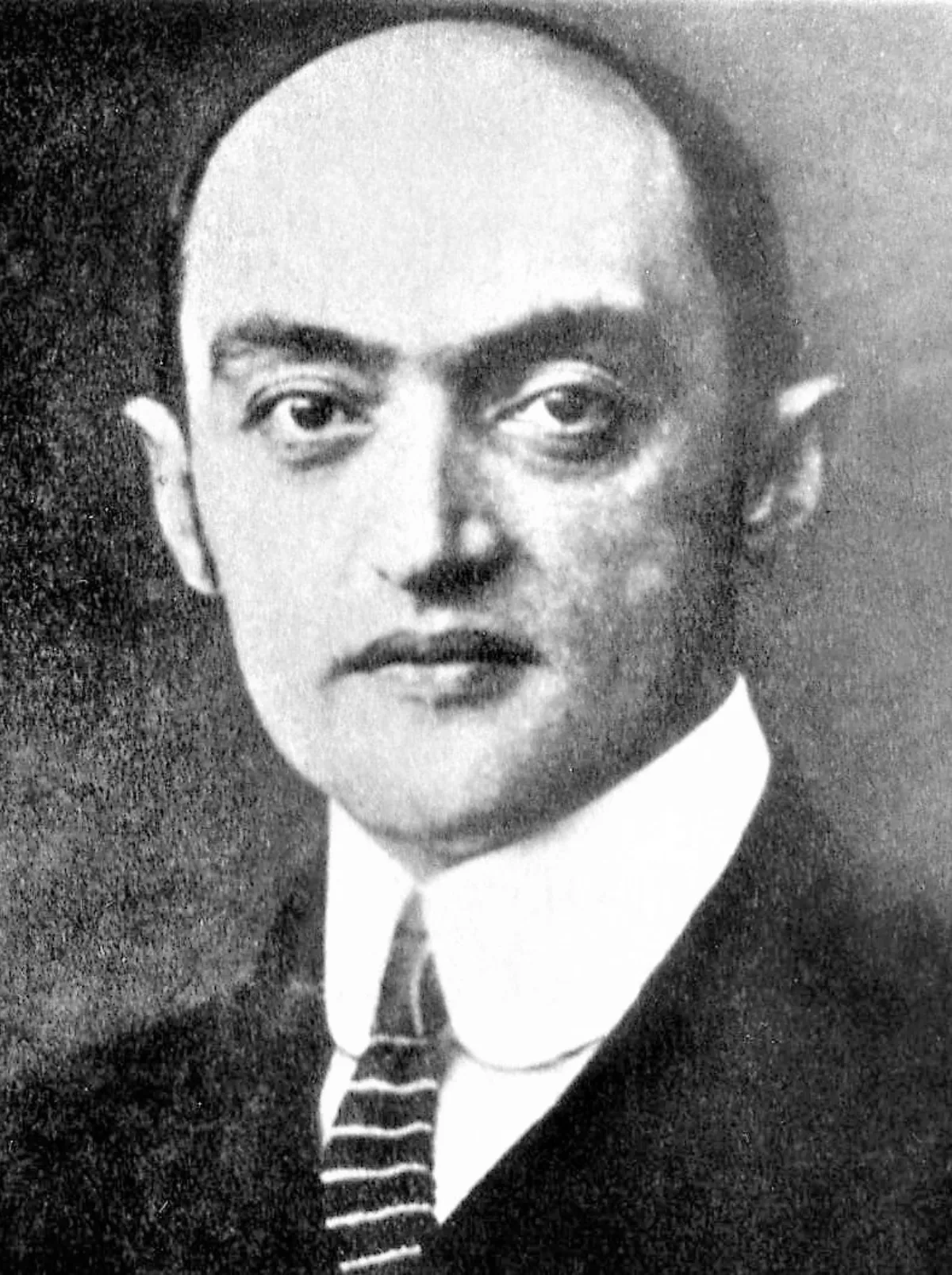

1. Joseph Schumpeter served briefly as Finance Minister of Austria in 1919.

1.

1. Joseph Schumpeter served briefly as Finance Minister of Austria in 1919.

Joseph Schumpeter was born in 1883 in Triesch, Habsburg Moravia, to German-speaking Catholic parents.

Joseph Schumpeter was educated at the Theresianum and began his career studying law at the University of Vienna under Eugen von Bohm-Bawerk, an economic theorist of the Austrian School.

Joseph Schumpeter taught economic theory and met Irving Fisher and Wesley Clair Mitchell.

In 1918, Joseph Schumpeter was a member of the Socialisation Commission established by the Council of the People's Deputies in Germany.

Joseph Schumpeter proposed a capital levy as a way to tackle the war debt and opposed the socialization of the Alpine Mountain plant.

Joseph Schumpeter was a board member at the Kaufmann Bank.

Joseph Schumpeter's resignation was a condition of the takeover of the Biedermann Bank in September 1924.

From 1925 until 1932, Joseph Schumpeter held a chair at the University of Bonn, Germany.

In 1932, Joseph Schumpeter moved to the United States, and soon began what would become extensive efforts to help fellow central European economists displaced by Nazism.

Joseph Schumpeter became known for his opposition to Marxism, although he still believed the triumph of socialism to be inevitable in the long run.

At Harvard, Joseph Schumpeter was considered a memorable character, erudite, and even showy in the classroom.

Joseph Schumpeter became known for his heavy teaching load and his personal and painstaking interest in his students.

Joseph Schumpeter served as the faculty advisor of the Graduate Economics Club and organized private seminars and discussion groups.

However, Joseph Schumpeter persevered, and in 1942 published what became the most popular of all his works, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, reprinted many times and in many languages in the following decades, as well as cited thousands of times.

The source of Joseph Schumpeter's dynamic, change-oriented, and innovation-based economics was the historical school of economics.

Joseph Schumpeter was influenced by Leon Walras and the Lausanne School, calling Walras the "greatest of all economists".

Joseph Schumpeter's scholarship is apparent in his posthumous History of Economic Analysis, Joseph Schumpeter thought that the greatest 18th-century economist was Turgot rather than Adam Smith, and he considered Leon Walras to be the "greatest of all economists", beside whom other economists' theories were "like inadequate attempts to catch some particular aspects of Walrasian truth".

The stationary state is, according to Joseph Schumpeter, described by Walrasian equilibrium.

In fashioning this theory connecting innovations, cycles, and development, Joseph Schumpeter kept alive the Russian Nikolai Kondratiev's ideas on 50-year cycles, Kondratiev waves.

Joseph Schumpeter suggested a model in which the four main cycles, Kondratiev, Kuznets, Juglar, and Kitchin can be added together to form a composite waveform.

Joseph Schumpeter thought that the institution enabling the entrepreneur to buy the resources needed to realize his vision was a well-developed capitalist financial system, including a whole range of institutions for granting credit.

Joseph Schumpeter emphasizes throughout this book that he is analyzing trends, not engaging in political advocacy.

Joseph Schumpeter disputed the idea that democracy was a process by which the electorate identified the common good, and politicians carried this out for them.

Joseph Schumpeter argued this was unrealistic, and that people's ignorance and superficiality meant that they were largely manipulated by politicians, who set the agenda.

Joseph Schumpeter defined democracy as the method by which people elect representatives in competitive elections to carry out their will.

Joseph Schumpeter faced pushback on his theory from other democratic theorists, such as Robert Dahl, who argued that there is more to democracy than simply the formation of government through competitive elections.

However, studies by Natasha Piano of the University of Chicago emphasize that Joseph Schumpeter had substantial disdain for elites as well.

In Mark I, Joseph Schumpeter argued that the innovation and technological change of a nation come from entrepreneurs or wild spirits.

Contrary to this prevailing opinion, Joseph Schumpeter argued that the agents that drive innovation and the economy are large companies that have the capital to invest in research and development of new products and services and to deliver them to customers more cheaply, thus raising their standard of living.

Joseph Schumpeter was the most influential thinker to argue that long cycles are caused by innovation and are an incident of it.

Joseph Schumpeter's treatise brought Kondratiev's ideas to the attention of English-speaking economists.

Joseph Schumpeter sees innovations as clustering around certain points in time that he refers to as "neighborhoods of equilibrium" when entrepreneurs perceive that risk and returns warrant innovative commitments.

Joseph Schumpeter identified innovation as the critical dimension of economic change.

Joseph Schumpeter argued that economic change revolves around innovation, entrepreneurial activities, and market power.

Joseph Schumpeter sought to prove that innovation-originated market power can provide better results than the invisible hand and price competition.

Joseph Schumpeter argued that technological innovation often creates temporary monopolies, allowing abnormal profits that would soon be competed away by rivals and imitators.

The World Bank's "Doing Business" report was influenced by Joseph Schumpeter's focus on removing impediments to creative destruction.

Joseph Schumpeter's second was Anna Reisinger, 20 years his junior and daughter of the concierge of the apartment where he grew up.

The loss of his wife and newborn son came only weeks after Joseph Schumpeter's mother had died.

Five years after arriving in the US, in 1937, at the age of 54, Joseph Schumpeter married the American economic historian Dr Elizabeth Boody, who helped him popularize his work and edited what became their magnum opus, the posthumously published History of Economic Analysis.

Joseph Schumpeter claimed that he had set himself three goals in life: to be the greatest economist in the world, to be the best horseman in all of Austria, and the greatest lover in all of Vienna.

Joseph Schumpeter said he had reached two of his goals, but he never said which two, although he is reported to have said that there were too many fine horsemen in Austria for him to succeed in all his aspirations.

Joseph Schumpeter died in his home in Taconic, Connecticut, at the age of 66, on the night of January 8,1950.

For some time after his death, Joseph Schumpeter's views were most influential among various heterodox economists, especially Europeans, who were interested in industrial organization, evolutionary theory, and economic development, and who tended to be on the other end of the political spectrum from Joseph Schumpeter and were often influenced by Keynes, Karl Marx, and Thorstein Veblen.

Robert Heilbroner was one of Joseph Schumpeter's most renowned pupils, who wrote extensively about him in The Worldly Philosophers.

Today, Joseph Schumpeter has a following outside standard textbook economics, in areas such as economic policy, management studies, industrial policy, and the study of innovation.

Joseph Schumpeter was probably the first scholar to develop theories about entrepreneurship.

The initial Joseph Schumpeter column praised him as a "champion of innovation and entrepreneurship" whose writing showed an understanding of the benefits and dangers of business that proved to be far ahead of its time.