1.

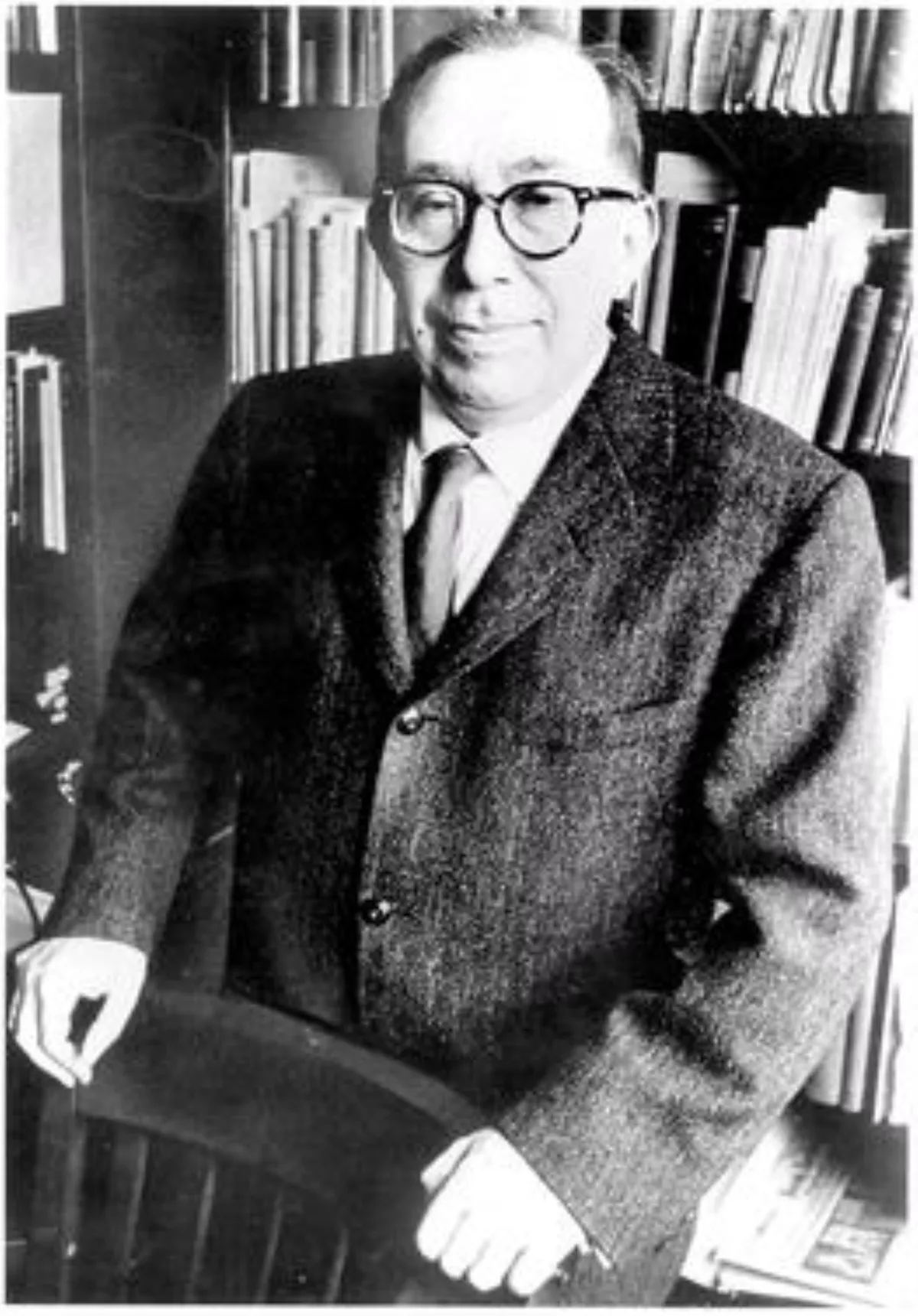

1. Leo Strauss was an American scholar of political philosophy.

1.

1. Leo Strauss was an American scholar of political philosophy.

Leo Strauss spent much of his career as a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, where he taught several generations of students and published fifteen books.

Leo Strauss himself noted that he came from a "conservative, even orthodox Jewish home", but one which knew little about Judaism except strict adherence to ceremonial laws.

Leo Strauss boarded with the Marburg cantor Strauss, whose residence served as a meeting place for followers of the neo-Kantian philosopher Hermann Cohen.

Leo Strauss served in the German army from World War I from July 5,1917, to December 1918.

Leo Strauss attended courses at the Universities of Freiburg and Marburg, including some taught by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger.

Leo Strauss had been engaged in a discourse with Carl Schmitt.

However, after Leo Strauss left Germany, he broke off the discourse when Schmitt failed to respond to his letters.

Leo Strauss adopted his wife's son, Thomas, and later his sister's child, Jenny Strauss Clay ; he and Miriam had no biological children of their own.

Leo Strauss became a lifelong friend of Alexandre Kojeve and was on friendly terms with Raymond Aron and Etienne Gilson.

Leo Strauss found shelter, after some vicissitudes, in England, where, in 1935 he gained temporary employment at the University of Cambridge with the help of his in-law David Daube, who was affiliated with Gonville and Caius College.

Unable to find permanent employment in England, Leo Strauss moved to the United States in 1937, under the patronage of Harold Laski, who made introductions and helped him obtain a brief lectureship.

Leo Strauss became a US citizen in 1944, and in 1949 became a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, holding the Robert Maynard Hutchins Distinguished Service Professorship until he left in 1969.

In 1953, Leo Strauss coined the phrase reductio ad Hitlerum, a play on reductio ad absurdum, suggesting that comparing an argument to one of Hitler's, or "playing the Nazi card", is often a fallacy of irrelevance.

Leo Strauss had received a call for a temporary lectureship in Hamburg in 1965 and received and accepted an honorary doctorate from the University of Hamburg and the German Order of Merit via the German representative in Chicago.

In 1969, Leo Strauss moved to Claremont McKenna College in California for a year, and then to St John's College, Annapolis in 1970, where he was the Scott Buchanan Distinguished Scholar in Residence until his death from pneumonia in 1973.

Leo Strauss was buried in Annapolis Hebrew Cemetery, with his wife Miriam Bernsohn Strauss, who died in 1985.

Leo Strauss's thought can be characterized by two main themes: the critique of modernity and the recovery of classical political philosophy.

Leo Strauss argued that modernity, which emerged among the 15th century Italian city states particularly in the writings of Niccolo Machiavelli, was a radical break from the tradition of Western civilization, and that it led to a crisis of nihilism, relativism, historicism, and scientism.

Leo Strauss claimed that modern political and social sciences, which were based on empirical observation and rational analysis, failed to grasp the essential questions of human nature, morality, and justice, and that they reduced human beings to mere objects of manipulation and calculation.

Leo Strauss criticized modern liberalism, which he saw as a product of modernity, for its lack of moral and spiritual foundations, and for its tendency to undermine the authority of religion, tradition, and natural law.

Leo Strauss advocated a careful and respectful reading of the classical texts, arguing that their authors wrote in an esoteric manner, which he called "the art of writing".

Leo Strauss suggested that the classical authors hid their true teachings behind a surface layer of conventional opinions, in order to avoid persecution and to educate only the few who were capable of grasping them, and that they engaged in a dialogue with each other across the ages.

Leo Strauss called this dialogue "the great conversation", and invited his readers to join it.

Leo Strauss argued that these philosophers, who lived under the rule of Islam, faced similar challenges as the ancient Greeks.

Leo Strauss claimed that these philosophers, who were both faithful to their revealed religions and loyal to the rational pursuit of philosophy, offered a model of how to reconcile reason and revelation, philosophy and theology, Athens and Jerusalem.

Leo Strauss regarded the trial and death of Socrates as the moment when political philosophy came into existence.

Leo Strauss distinguished "scholars" from "great thinkers," identifying himself as a scholar.

Leo Strauss wrote that most self-described philosophers are in actuality scholars, cautious and methodical.

In Natural Right and History, Leo Strauss begins with a critique of Max Weber's epistemology, briefly engages the relativism of Martin Heidegger and continues with a discussion of the evolution of natural rights via an analysis of the thought of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke.

Leo Strauss concludes by critiquing Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Edmund Burke.

Indeed, Leo Strauss wrote that Heidegger's thinking must be understood and confronted before any complete formulation of modern political theory is possible, and this means that political thought has to engage with issues of ontology and the history of metaphysics.

Leo Strauss wrote that Friedrich Nietzsche was the first philosopher to properly understand historicism, an idea grounded in a general acceptance of Hegelian philosophy of history.

Explicitly following Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's lead, Leo Strauss indicates that medieval political philosophers, no less than their ancient counterparts, carefully adapted their wording to the dominant moral views of their time, lest their writings be condemned as heretical or unjust, not by "the many", but by those "few" whom the many regarded as the most righteous guardians of morality.

Leo Strauss traced its roots in Enlightenment philosophy to Max Weber, a thinker whom Strauss described as a "serious and noble mind".

Weber wanted to separate values from science but, according to Leo Strauss, was really a derivative thinker, deeply influenced by Nietzsche's relativism.

Leo Strauss treated politics as something that could not be studied from afar.

Two significant political-philosophical dialogues Leo Strauss had with living thinkers were those he held with Carl Schmitt and Alexandre Kojeve.

Leo Strauss believed that such an analysis, as in Hobbes's time, served as a useful "preparatory action," revealing our contemporary orientation towards the eternal problems of politics.

However, Leo Strauss believed that Schmitt's reification of our modern self-understanding of the problem of politics into a political theology was not an adequate solution.

Leo Strauss instead advocated a return to a broader classical understanding of human nature and a tentative return to political philosophy, in the tradition of the ancient philosophers.

The political-philosophical dispute between Kojeve and Leo Strauss centered on the role that philosophy should and can be allowed to play in politics.

Leo Strauss argued that philosophers should have an active role in shaping political events.

Leo Strauss argued that liberalism in its modern form, contained within it an intrinsic tendency towards extreme relativism, which in turn led to two types of nihilism:.

Leo Strauss argued that the city-in-speech was unnatural, precisely because "it is rendered possible by the abstraction from eros".

Leo Strauss spoke of the danger in trying finally to resolve the debate between rationalism and traditionalism in politics.

Leo Strauss agreed with a letter of response to his request of Eric Voegelin to look into the issue.

Leo Strauss proceeded to show this letter to Kurt Riezler, who used his influence in order to oppose Popper's appointment at the University of Chicago.

Leo Strauss constantly stressed the importance of two dichotomies in political philosophy, namely Athens and Jerusalem and Ancient versus Modern.

Leo Strauss wrote several essays about its controversies but left these activities behind by his early twenties.

Leo Strauss argued that the author did not provide enough proof for his argument.

Leo Strauss was openly disdainful of atheism and disapproved of contemporary dogmatic disbelief, which he considered intemperate and irrational.

Leo Strauss's works were read and admired by thinkers as diverse as the philosophers Gershom Scholem, Walter Benjamin, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Alexandre Kojeve, and the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan.

Almost the entirety of Leo Strauss's writings has been translated into Chinese.

However, this seems like a false premise, as most authors Leo Strauss refers to in his work lived in times when only the social elites were literate enough to understand works of philosophy.

Some critics of Leo Strauss have accused him of being elitist, illiberal and anti-democratic.

Journalists such as Seymour Hersh have opined that Leo Strauss endorsed noble lies, "myths used by political leaders seeking to maintain a cohesive society".

Drury argues that Leo Strauss teaches that "perpetual deception of the citizens by those in power is critical because they need to be led, and they need strong rulers to tell them what's good for them".

Nicholas Xenos similarly argues that Leo Strauss was "an anti-democrat in a fundamental sense, a true reactionary".

Leo Strauss, Ryn argues, wrongly and reductively assumes that respect for tradition must undermine reason and universality.

Leo Strauss's anti-historical thinking connects him and his followers with the French Jacobins, who regarded tradition as incompatible with virtue and rationality.

In particular, Leo Strauss argued that Plato's myth of the philosopher king should be read as a reductio ad absurdum, and that philosophers should understand politics not in order to influence policy but to ensure philosophy's autonomy from politics.