1.

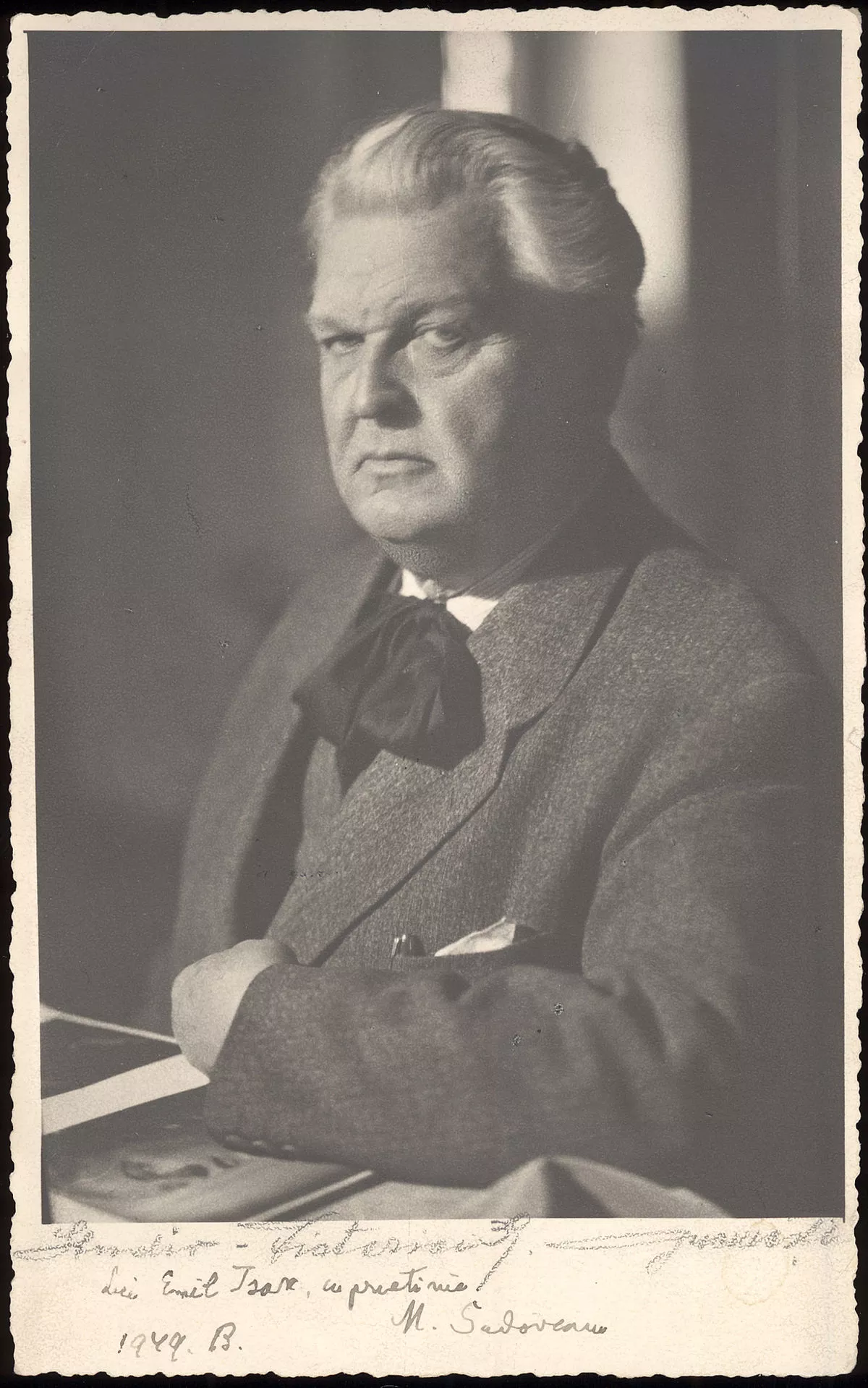

1. An author whose career spanned five decades, Mihail Sadoveanu was an early associate of the traditionalist magazine Samanatorul, before becoming known as a Realist writer and an adherent to the Poporanist current represented by Viata Romaneasca journal.