1.

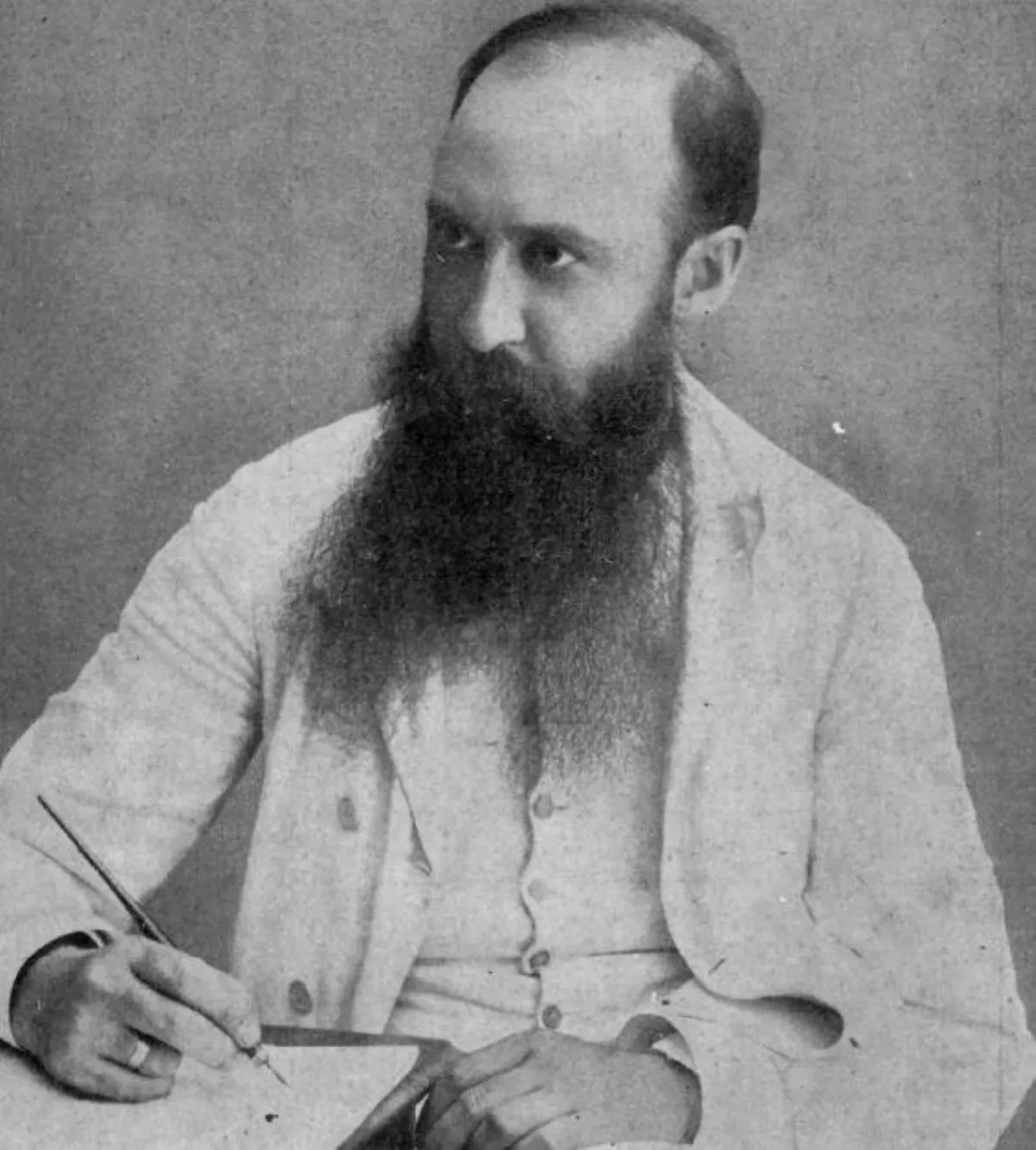

1. Nicolae Iorga was a historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet and playwright.

1.

1. Nicolae Iorga was a historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet and playwright.

Nicolae Iorga's activity included the transformation of Valenii de Munte town into a cultural and academic center.

In parallel with his academic contributions, Nicolae Iorga was a prominent right-of-centre activist, whose political theory bridged conservatism, Romanian nationalism, and agrarianism.

Nicolae Iorga later became a leadership figure at Samanatorul, the influential literary magazine with populist leanings, and militated within the League for the Cultural Unity of All Romanians, founding vocally conservative publications such as Neamul Romanesc, Drum Drept, Cuget Clar and Floarea Darurilor.

Nicolae Iorga was an adversary of the dominant National Liberals, later involved with the opposition Romanian National Party.

Later in his life, Nicolae Iorga opposed the radically fascist Iron Guard, and, after much oscillation, came to endorse its rival King Carol II.

Nicolae Iorga remained an independent voice of opposition after the Guard inaugurated its own National Legionary dictatorship, but was ultimately assassinated by a Guardist commando.

Nicolae Iorga was born in Botosani into a family of Greek origin.

Nicolae Iorga's father, Nicu Iorga, was a practicing lawyer; he ultimately descended from a Greek merchant who had settled in Botosani in the 18th century five generations before Nicolae Iorga's birth.

Nicolae Iorga's mother, Zulnia Iorga, was a woman of Phanariote Greek descent.

Nicolae Iorga claimed direct descent from the noble Mavrocordatos and Argyros families.

Nicolae Iorga is generally believed to have been born on 17 January 1871, although his birth certificate provides a date of 6 June.

Nicolae Iorga credited the 19th-century polymath Mihail Kogalniceanu, whose works he first read as a child, with having shaped this literary preference.

In 1883, Nicolae Iorga began tutoring some of his colleagues to supplement his family's main revenue.

Nicolae Iorga was already fluent in French, Italian, Latin and Greek; he later referred to Greek studies as "the most refined form of human reasoning".

Nicolae Iorga first grew interested in political activities for the first time but displayed convictions which he later strongly disavowed; a self-described Marxist, Iorga promoted the left-wing magazine Viata Sociala and lectured on Das Kapital.

Nicolae Iorga was suspended a third time for reading during a teacher's lesson but graduated in the top "first prize" category and subsequently took his Baccalaureate with honors.

In 1888, Nicolae Iorga passed his entry examination for the University of Iasi Faculty of Letters, becoming eligible for a scholarship soon after.

Nicolae Iorga expanded his contribution as an opinion journalist, publishing with some regularity in various local or national periodicals of various leanings, from the socialist Contemporanul and Era Noua to Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu's.

Also in 1890, Nicolae Iorga married Maria Tasu, whom he was to divorce in 1900.

Nicolae Iorga had previously been in love with an Ecaterina C Botez, but, after some hesitation, decided to marry into the family of man Vasile Tasu, much better situated in the social circles.

Xenopol, who was Nicolae Iorga's matchmaker, tried to obtain for Nicolae Iorga a teaching position at Iasi University.

Nicolae Iorga was a contributor for the Encyclopedie francaise, personally recommended there by Slavist Louis Leger.

Somewhat dissatisfied with French education, Nicolae Iorga presented his dissertation and, in 1893, left for the German Empire, attempting to enlist in the University of Berlin's PhD program.

Nicolae Iorga's working paper, on Thomas III of Saluzzo, was not received, because Iorga had not spent three years in training, as required.

Nicolae Iorga spent his time further investigating the historical sources, at archives in Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden.

Nicolae Iorga met, befriended and often collaborated with fellow historians from European countries other than Romania: the editors of Revue de l'Orient Latin, who first published studies Iorga later grouped in the six volumes of and Frantz Funck-Brentano, who enlisted his parallel contribution for Revue Critique.

Nicolae Iorga's articles were featured in two magazines for ethnic Romanian communities in Austria-Hungary: Familia and Vatra.

Nicolae Iorga changed residence several times, until eventually settling in Gradina Icoanei area.

Nicolae Iorga agreed to compete in a sort of debating society, with lectures which only saw print in 1944.

Nicolae Iorga applied for the Medieval History Chair at the University of Bucharest, submitting a dissertation in front of an examination commission comprising historians and philosophers, but totaled a 7 average which only entitled him to a substitute professor's position.

Nicolae Iorga was again out of the country in 1895, visiting the Netherlands and, again, Italy, in search of documents, publishing the first section of his extended historical records' collection, his Romanian Atheneum conference on Michael the Brave's rivalry with condottiero Giorgio Basta, and his debut in travel literature.

Nicolae Iorga published the second part of and the printed rendition of the de Mezieres study.

In 1897, the year when he was elected a corresponding member of the academy, Nicolae Iorga traveled back to Italy and spent time researching more documents in the Austro-Hungarian Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, at Dubrovnik.

Nicolae Iorga oversaw the publication of the 10th Hurmuzachi volume, grouping diplomatic reports authored by Kingdom of Prussia diplomats in the two Danubian Principalities.

Also in 1899, Nicolae Iorga inaugurated his contribution to the Bucharest-based French-language newspaper L'Independance Roumaine, publishing polemical articles on the activity of his various colleagues and, as a consequence, provoking a lengthy scandal.

In 1901, shortly after his divorce from Maria, Nicolae Iorga married Ecaterina, the sister of his friend and colleague Ioan Bogdan.

Nicolae Iorga, who had convinced Lamprecht not to assign this task to Xenopol, completed.

Interested in recovering the Romanian contributions to Transylvanian history, in particular Michael the Brave's precursory role in Romanian unionism, Nicolae Iorga spent his time reviewing, copying and translating Hungarian-language historical texts with much assistance from his wife.

Nicolae Iorga was by then making known his newly found interest in cultural nationalism and national didacticism, as expressed by him in an open letter to Goga's Budapest-based Luceafarul magazine.

Nicolae Iorga was involved in a new project of researching the content of archives throughout Moldavia and Wallachia, and, having reassessed the nationalist politics of Junimist poet Mihai Eminescu, helped collect and publish a companion to Eminescu's work.

Also in 1903, Nicolae Iorga became one of the managers of Samanatorul review.

In tandem with his full return to cultural and political journalism, which included prolonged debates with both the "old" historians and the Junimists, Nicolae Iorga was still active at the forefront of historical research.

Nicolae Iorga later confessed that the book was an integral part of his and Haret's didacticist agenda, supposed to be "spread to the very bottom of the country in thousands of copies".

Nicolae Iorga ran in the 1905 election and won a seat in Parliament's lower chamber.

Nicolae Iorga remained politically independent until 1906, when he attached himself to the Conservative Party, making one final attempt to change the course of Junimism.

Nicolae Iorga's move was contrasted by the group of left-nationalists from the Poporanist faction, who were allied to the National Liberals and, soon after, in open conflict with Iorga.

The perception that Nicolae Iorga was a xenophobe drew condemnation from more moderate traditionalist circles, in particular the Viata Literara weekly.

Nicolae Iorga eventually parted with in late 1906, moving on to set up his own tribune, Neamul Romanesc.

Nicolae Iorga's published scientific contributions for that year include, among others, an English-language study on the Byzantine Empire.

However, Nicolae Iorga's popularity was still increasing, and, carried by this sentiment, he was first elected to Chamber during the elections of that same year.

Once settled, Nicolae Iorga set up a specialized summer school, his own publishing house, a printing press and the literary supplement of, as well as an asylum managed by writer Constanta Marino-Moscu.

Nicolae Iorga published some 25 new works for that year, such as the introductory volumes for his German-language companion to Ottoman history, a study on Romanian Orthodox institutions, and an anthology on Romanian Romanticism.

At that stage in his life, Nicolae Iorga became an honorary member of the Romanian Writers' Society.

Nicolae Iorga had militated for its creation in both and, but wrote against its system of fees.

Nicolae Iorga alienated the main Romanian organizations in Transylvania: the Romanian National Party dreaded his proposal to boycott the Diet of Hungary, particularly since PNR leaders were contemplating a loyalist "Greater Austria" devolution project.

In 1910, the year when he toured the Old Kingdom's conference circuit, Nicolae Iorga again rallied with Cuza to establish the explicitly antisemitic Democratic Nationalist Party.

Also in 1910, Nicolae Iorga published some thirty new works, covering gender history, Romanian military history and Stephen the Great's Orthodox profile.

Additionally, Nicolae Iorga produced the first of several studies dealing with Balkan geopolitics in the charged context leading up to the Balkan Wars.

Nicolae Iorga made a noted contribution to ethnography, with.

In 1913, Nicolae Iorga was in London for an International Congress of History, presenting a proposal for a new approach to medievalism and a paper discussing the sociocultural effects of the fall of Constantinople on Moldavia and Wallachia.

Nicolae Iorga was even called under arms in the Second Balkan War, during which Romania fought alongside Serbia and against the Kingdom of Bulgaria.

That same year, Nicolae Iorga issued the first series of his Drum Drept monthly, later merged with the magazine Ramuri.

Nicolae Iorga managed to publish roughly as many new titles in 1914, the year when he received a Romanian distinction, and inaugurated the international Institute of South-East European Studies or ISSEE, with a lecture on Albanian history.

Nicolae Iorga's hesitation was ridiculed by hawkish Eugen Lovinescu as pro-Transylvanian but anti-war, costing Iorga his office in the Cultural League.

Nicolae Iorga was introduced to the private circle of Romania's young King, Ferdinand I, whom he found well-intentioned but weak-willed.

Nicolae Iorga is sometimes credited as a tutor to Crown Prince Carol, who reportedly attended the Valenii school.

Nicolae Iorga gave a final touch to the collection, comprising his commentary on 30,000 individual documents and spread over 31 tomes.

Still a member of Parliament, Nicolae Iorga joined the authorities in the provisional capital of Iasi, but opposed the plans of relocating government out of besieged Moldavia and into the Russian Republic.

Nicolae Iorga translated from English and printed My Country, a patriotic essay by Ferdinand's wife Marie of Edinburgh.

The conditions were judged humiliating by Nicolae Iorga ; he refused to regain his University of Bucharest chair.

Nicolae Iorga only returned to Bucharest as Romania resumed its contacts with the Allies and the left the country.

Nicolae Iorga was reelected to the lower chamber in the June 1918 election, becoming President of the body and, due to the rapid political developments, the first person to hold this office in the history of Greater Romania.

Shortly after the creation of Greater Romania, Nicolae Iorga was focusing his public activity on exposing collaborators of the wartime occupiers.

Nicolae Iorga failed at enlisting support for the purge of Germanophile professors from university, but the attempt rekindled the feud between him and Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcas, who had served in the German-appointed administration.

The elections seemed to do away with the old political system: Nicolae Iorga's party was third, trailing behind two newcomers, the Transylvanian PNR and the Poporanist Peasants' Party, with whom it formed a parliamentary bloc supporting an Alexandru Vaida-Voevod cabinet.

Also in 1919, Nicolae Iorga was elected chairman of the Cultural League, where he gave a speech on "the Romanians' rights to their national territory", was appointed head of the Historical Monuments' Commission, and met the French academic mission to Romania.

Nicolae Iorga was in correspondence with intellectuals of all backgrounds, and, reportedly, the Romanian who was addressed the most letters in postal history.

Nicolae Iorga was awarded the title of doctor honoris causa by the University of Strasbourg, while his lectures on Albania, collected by poet Lasgush Poradeci, became.

In Bucharest, Nicolae Iorga received as a gift from his admirers a new Bucharest home on Bonaparte Highway.

At that stage, Nicolae Iorga was resenting the PNR for holding onto its regional government of Transylvania, and criticizing the PT for its claim to represent all Romanian peasants.

Progressively after that moment, Nicolae Iorga began toning down his antisemitism, a process of the end of which Cuza left the Democratic Nationalists to establish the more militant National-Christian Defense League.

Nicolae Iorga's publishing activity continued at a steady pace during that year, when he first presided over the Romanian School of Fontenay-aux-Roses; he issued the two volumes of and the three tomes of, alongside, and some other scholarly works.

Nicolae Iorga resumed his writing for the stage, with two new drama plays: one centered on the Moldavian ruler Constantin Cantemir, the other dedicated to, and named after, Brancoveanu.

In politics, Nicolae Iorga began objecting to the National Liberals' hold on power, denouncing the 1922 election as a fraud.

Nicolae Iorga resumed his close cooperation with the PNR, briefly joining the party ranks in an attempt to counter this monopoly.

Nicolae Iorga began lecturing at Ramiro Ortiz's Italian Institute in Bucharest.

In 1925, when he was elected a member of the Krakow Academy of Learning in Poland, Nicolae Iorga gave conferences in various European countries, including Switzerland.

Nicolae Iorga was again abroad in 1926 and 1927, lecturing on various subjects at reunions in France, Italy, Switzerland, Denmark, Spain, Sweden and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, many of his works being by then translated into French, English, German and Italian.

At home, the PND's merge into the PNR, accepted by Nicolae Iorga, was stopped once the historian asked to become the resulting union's chief.

Nicolae Iorga embarked on a longer journey during 1930: again lecturing in Paris during January, he left for Genoa and, from there, traveled to the United States, visiting some 20 cities, being greeted by the Romanian-American community and meeting with President Herbert Hoover.

Nicolae Iorga was an honored guest of Case Western Reserve University, where he delivered a lecture in English.

The backdrop to Nicolae Iorga's mandate was Carol's conflict with the Iron Guard, an increasingly popular fascist organization.

In March 1932, Nicolae Iorga signed a decree outlawing the movement, the beginning of his clash with the Guard's founder Corneliu Zelea Codreanu.

The major issue facing Nicolae Iorga was the economic crisis, part of the Great Depression, and he was largely unsuccessful in tackling it.

Nicolae Iorga's premiership evidenced the growing tensions between the PND in Bucharest and its former allies in Transylvania: Iorga arrived to power after rumors of a PNT "Transylvanian conspiracy", and his cabinet included no Romanian Transylvanian politicians.

Nicolae Iorga presented his cabinet's resignation in May 1932, returning to academic life.

Nicolae Iorga concentrated on redacting memoirs, published as, whereby he intended to counter political hostility.

Nicolae Iorga created the Museum of Sacred Art, housed by the Cretulescu Palace.

In later years, Nicolae Iorga feuded with his Transylvanian disciple Lucian Blaga, trying in vain to block Blaga's reception to the academy over differences in philosophy and literary preference.

On his way to a pan-European congress, Nicolae Iorga stirred further controversy by attending, in Rome, the tenth anniversary of the 1922 March, celebrating Italian Fascism.

Nicolae Iorga resumed his participation in conference cycles during 1933, revisiting France, as well as taking back his position at the University of Bucharest; he published another 37 books and, in August 1933, attended the History Congress in Warsaw.

Early in 1934, Iorga issued a condemnation of the Iron Guard, following the assassination of National Liberal Premier Ion G Duca by a Legionary death squad.

However, during the subsequent police round-ups of Guardist activists, Nicolae Iorga intervened for the release of fascist philosopher Nae Ionescu, and still invited Guardist poet Radu Gyr to lecture at Valenii.

Nicolae Iorga again toured Europe in 1935, and, upon his return to Romania, gave a new set of conferences under the auspices of the Cultural League, inviting scholar Franz Babinger to lecture at the ISSEE.

Early in 1936, Nicolae Iorga was again lecturing at the University of Paris, and gave an additional conference at the Societe des etudes historiques, before hosting the Bucharest session of the International Committee of Historians.

Nicolae Iorga was in the Netherlands, with a lecture on Byzantine social history:.

Nicolae Iorga completed several new volumes, among which were, the polemical essay, and the first two volumes of the long planned.

Nicolae Iorga was officially honored in 1937, when Carol II inaugurated a Bucharest Museum of World History, placed under the ISSEE director's presidency.

However, the publicized death threats he received from the Iron Guard eventually prompted Nicolae Iorga to retire from his university position.

Nicolae Iorga withdrew to Valenii de Munte, but was still active on the academic scene, lecturing on "the development of the human spirit" at the World History Institute, and being received as a corresponding member into Chile's Academy of History.

Nicolae Iorga mentored German biographer Eugen Wolbe, who collected data on the Romanian kings.

Nicolae Iorga attended the Cultural League congress in Iasi, where he openly demanded for the Iron Guard to be outlawed on the grounds that it served Nazi interests, and discussed the threat of war in his speeches at Valenii de Munte and his Radio conferences.

The early months of 1938 saw Nicolae Iorga joining the national unity government of Miron Cristea, formed by Carol II's right-wing power base.

Nicolae Iorga was upset by the imposition of uniforms on all public officials, calling it "tyrannical", and privately ridiculed the new constitutional regime's architects, but he eventually complied to the changes.

Nicolae Iorga himself refused to attend the trial; in letters he addressed to the judges, he asked the count of libel to be withdrawn, and advised that Codreanu should follow the insanity defense on the other accusations.

In 1939, as the Guard's campaign of retribution had degenerated into terrorism, Nicolae Iorga used the Senate tribune to address the issue and demand measures to curb the violence.

Nicolae Iorga was absent for part of the year, again lecturing in Paris.

Also in 1938, Nicolae Iorga inaugurated the open-air theater of Valenii de Munte with one of his own dramatic texts,.

Nicolae Iorga was again Romanian Commissioner of the Venice Biennale in 1940.

Nicolae Iorga was troubled by the outbreak of World War II and saddened by the fall of France, events which formed the basis of his essay.

Nicolae Iorga was working on a version of Prometheus Bound, a tragedy which probably reflected his concern about Romania, her allies, and the uncertain political future.

Nicolae Iorga further antagonized the new government by stating his attachment to the abdicated royal.

Nicolae Iorga then moved to Sinaia, where he gave the finishing touches to his book.

Nicolae Iorga's killing is often mentioned in tandem with that of agrarian politician Virgil Madgearu, kidnapped and murdered by the Guardists on the same night, and with the Jilava massacre.

Nicolae Iorga's death caused much consternation among the general public, and was received with particular concern by the academic community.

Borrowing Maiorescu's theory about how Westernization had come to Romania as "forms without concept", Nicolae Iorga likewise aimed it against the liberal establishment, but gave it a more radical expression.

Nicolae Iorga's response to the Jacobin model was an Anglophile and Tocquevillian position, favoring the British constitutional system and praising the American Revolution as the positive example of nation-building.

In rejecting pure individualism, Nicolae Iorga reacted against the modern reverence toward Athenian democracy or the Protestant Reformation, giving more positive appraisals to other community models: Sparta, Macedonia, the Italian city-states.

In Stanomir's assessment, this last period of Nicolae Iorga's activity implied a move toward the main sources of traditional conservatism, bringing Nicolae Iorga closer to the line of thought represented by Edmund Burke, Thomas Jefferson or Mihail Kogalniceanu, and away from that of Eminescu.

Nicolae Iorga found himself in Kogalniceanu's conservative statement, "civilization stops when revolutions begin", being especially critical of communist revolution.

Nicolae Iorga described the Soviet experiment as a "caricature" of the Jacobin age and communist leader Joseph Stalin as a dangerous usurper.

Nicolae Iorga found the small Romanian Communist Party an amusement and, even though he expressed alarm for its terrorist tendencies and its "foreign" nature, disliked the state's use of brutal methods against its members.

Nicolae Iorga had nevertheless opted for religious-cultural over racial antisemitism, believing that, at the core of civilization, there was a conflict between Christian values and Judaism.

Nicolae Iorga recorded being touched by his warm reception among the Romanian American Jewish community in 1930, and, after 1934, published his work with the Adevarul group.

Nicolae Iorga's changing sentiment flowed between the extremes of Francophilia and Francophobia.

Nicolae Iorga recalled that, in the 1890s, he had been shocked by the irreverence and cosmopolitanism of French student society.

Shortly after the beginning of World War I, during the Battle of the Frontiers, Nicolae Iorga publicized his renewed love for France, claiming that she was the only belligerent engaged in a purely defensive war; in the name of Pan-Latinism, he later chided Spain for keeping neutral.

Nicolae Iorga later called Germany's Bohemia Protectorate a "Behemoth", referring to its annexation as a "prehistoric" act.

The conservative Nicolae Iorga was however inclined to sympathize with other forms of totalitarianism or corporatism, and, since the 1920s, viewed Italian Fascism with some respect.

Nicolae Iorga was noted for fostering the academic career of Eufrosina Dvoichenko-Markov, one of the few Russian-Romanian researchers of the interwar period.

Nicolae Iorga was however skeptical about the Ukrainian identity and rejected the idea of an independent Ukraine on Romania's border, debating the issues with ethnographer Zamfir Arbore.

Various of Nicolae Iorga's tracts speak in favor of a common background uniting the diverse nations of the Balkans.

Bulgarian historian Maria Todorova suggests that, unlike many of his predecessors, Nicolae Iorga was not alarmed Romania being perceived as a Balkan country, and did not attach a negative connotation to this affiliation.

However, even at that stage, Nicolae Iorga's ideas accommodated a belief that history needed to be written with a "poetic talent" that would make one "relive" the past.

Nicolae Iorga would speak of historians as "elders of [their] nation", and dismissed academic specialization as a "blindfold".

Calinescu suggests that Nicolae Iorga was an "anachronistic" type in his context: "approved only by failures", aged before his time, modeling himself on ancient chroniclers and out of place in modern historiography.

Nicolae Iorga had a friendly attitude toward other Hungarian scholars, including Arpad Bitay and Imre Kadar, who were his guests at Valenii.

Ioana Both notes: "A creator with titan-like forces, Nicolae Iorga is more a visionary of history than a historian".

Some of Nicolae Iorga's studies focused specifically on the original events in the process: ancient Dacia's conquest by the Roman Empire, and the subsequent foundation of Roman Dacia.

Nicolae Iorga's account is decidedly in support of Romania's Roman roots, and even suggests that Romanization preceded the actual conquest.

Nicolae Iorga was nevertheless explicit in distancing himself from the speculative texts of Dacianist Nicolae Densusianu, where Dacia was described as the source of all European civilization.

Nicolae Iorga had a complex personal perspective on the little-documented Dark Age history, between the Roman departure and the 14th century emergence of two Danubian Principalities: Moldavia and Wallachia.

Nicolae Iorga supposed that, during the 12th century, there was an additional symbiosis between settled Vlachs and their conquerors, the nomadic Cumans.

Unlike Ioan Bogdan and others, Nicolae Iorga strongly rejected any notion that the South Slavs had been an additional contributor to ethnogenesis, and argued that Slavic idioms were a sustained but nonessential influence in historical Romanian.

The stately foundation of Moldavia and of Wallachia, Nicolae Iorga thought, were linked to the emergence of major trade routes in the 14th century, and not to the political initiative of military elites.

Likewise, Nicolae Iorga looked into the genesis of boyardom, describing the selective progression of free peasants into a local aristocracy.

Nicolae Iorga described the later violent clash between hospodars and boyars as one between national interest and disruptive centrifugal tendencies, suggesting that prosperous boyardom had undermined the balance of the peasant state.

Panaitescu was however more categorical than Nicolae Iorga in affirming that Michael the Brave's expeditions were motivated by political opportunism rather than by a pan-Romanian national awareness.

Nicolae Iorga described the "Byzantine man" as embodying the blend of several cultural universes: Greco-Roman, Levantine and Eastern Christian.

Nicolae Iorga's writings insisted on the importance of Byzantine Greek and Levantine influences in the two countries after the fall of Constantinople: his notion of "Byzantium after Byzantium" postulated that the cultural forms produced by the Byzantine Empire had been preserved by the Principalities under Ottoman suzerainty.

Nicolae Iorga recommended artists to study handicrafts, even though, an adversary of the pastiche, he strongly objected to Brancovenesc revival style taken up by his generation.

Nicolae Iorga wrote with noted warmth about Contemporanul and its cultural agenda, but concluded that Poporanists represented merely "the left-wing current of the National Liberal Party".

In some of his essays, Nicolae Iorga identified Expressionism with the danger of Germanization, a phenomenon he described as "intolerable".

The ensuing polemics were often bitter, and Nicolae Iorga's vehemence was met with ridicule by his modernist adversaries.

Nicolae Iorga's views were in part responsible for a split taking place at, occurring when his traditionalist disciple, Nichifor Crainic, became the group's new leader and marginalized the Expressionists.

Nicolae Iorga was the subject of a special issue, being recognized as a forerunner.

In 1930s Bessarabia, Nicolae Iorga's ideology helped influence poet Nicolai Costenco, who created Viata Basarabiei as a local answer to Cuget Clar.

One voice in support of this view is that of Ion Petrovici, a Junimist academic, who recounted that hearing Nicolae Iorga lecture had made him overcome a prejudice which rated Maiorescu above all Romanian orators.

Tudor Vianu believed it "amazing" that, even in 1894, Nicolae Iorga had made "so rich a synthesis of the scholarly, literary and oratorical formulas".

Critic Ion Simut suggests that Nicolae Iorga is at his best in travel writing, combining historical fresco and picturesque detail.

Nicolae Iorga was a highly productive dramatist, inspired by the works of Carlo Goldoni, William Shakespeare, Pierre Corneille and the Romanian Barbu Stefanescu Delavrancea.

Literary historian Nicolae Manolescu found some of the texts in question illegible, but argued: "It is inconceivable that Iorga's theater is entirely obsolete".

In old age, Nicolae Iorga had established his reputation as a memoirist: was described by Victor Iova as "a masterpiece of Romanian literature".

Notably in this context, Nicolae Iorga reserved praise for some who had supported the Central Powers, but stated that actual collaboration with the enemy was unforgivable.

One early example is a biting epigram by Ion Luca Caragiale, where Nicolae Iorga is described as the dazed savant.

One of Teodoreanu's own epigrams in Contimporanul ridiculed, showing the resurrected Dante Alighieri pleading with Nicolae Iorga to be left in peace.

Later, Nicolae Iorga's appearance inspired the works of some other visual artists, including his own daughter Magdalina Nicolae Iorga, painter Constantin Piliuta and sculptor Ion Irimescu, who was personally acquainted with the scholar.

Irimescu's busts of Nicolae Iorga are located in places of cultural importance: the ISSEE building in Bucharest and a public square in Chisinau, Moldova.

Since 1994, Nicolae Iorga's face is featured on a highly circulated Romanian leu bill: the 10,000 lei banknote, which became the 1 leu bill following a 2005 monetary reform.

Nicolae Iorga was promoted to the national communist pantheon as an "anti-fascist" and "progressive" intellectual, and references to his lifelong anti-communism were omitted.

In 1988, Nicolae Iorga was the subject of Drumet in calea lupilor, a Romanian film directed by Constantin Vaeni.

Nicolae Iorga's work was selectively reinterpreted by protochronists such as Dan Zamfirescu, Mihai Ungheanu and Corneliu Vadim Tudor.

Nicolae Iorga has enjoyed posthumous popularity in the decades since the Romanian Revolution of 1989: present at the top of "most important Romanians" polls in the 1990s, he was voted in at No 17 in the 100 greatest Romanians televised poll.

Nicolae Iorga had over ten children from his marriages, but many of them died in infancy.

The only one of his children to train in history, known for her work in reediting her father's books and her contribution as a sculptor, Liliana Nicolae Iorga married fellow historian Dionisie Pippidi in 1943.

Mircea Nicolae Iorga was married into the aristocratic Stirbey family, and then to Mihaela Bohatiel, a Transylvanian noblewoman who was reputedly a descendant of the Lemeni clan and of the medieval magnate Johannes Benkner.

Nicolae Iorga was for a while attracted to PND politics and wrote poetry.