1.

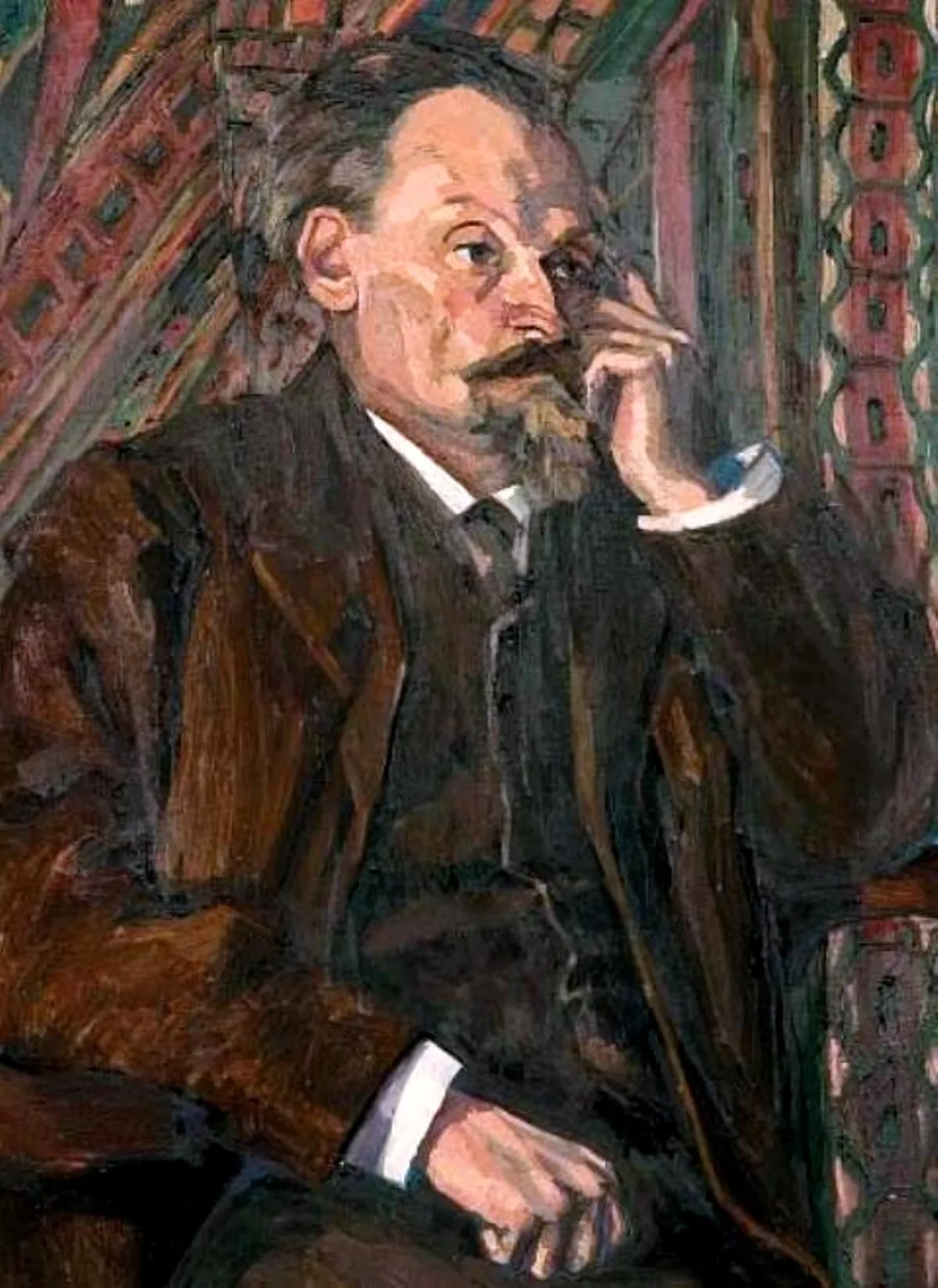

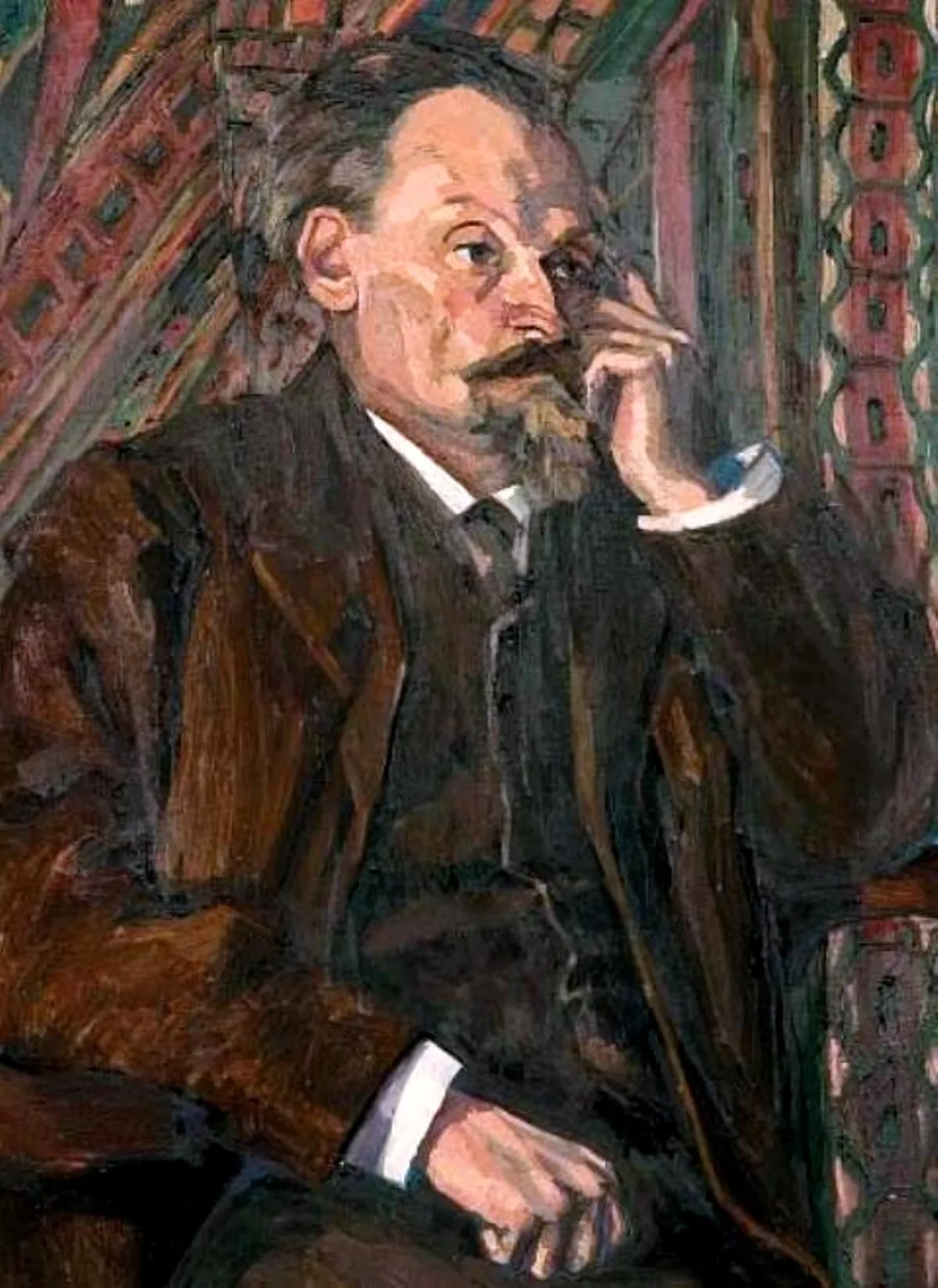

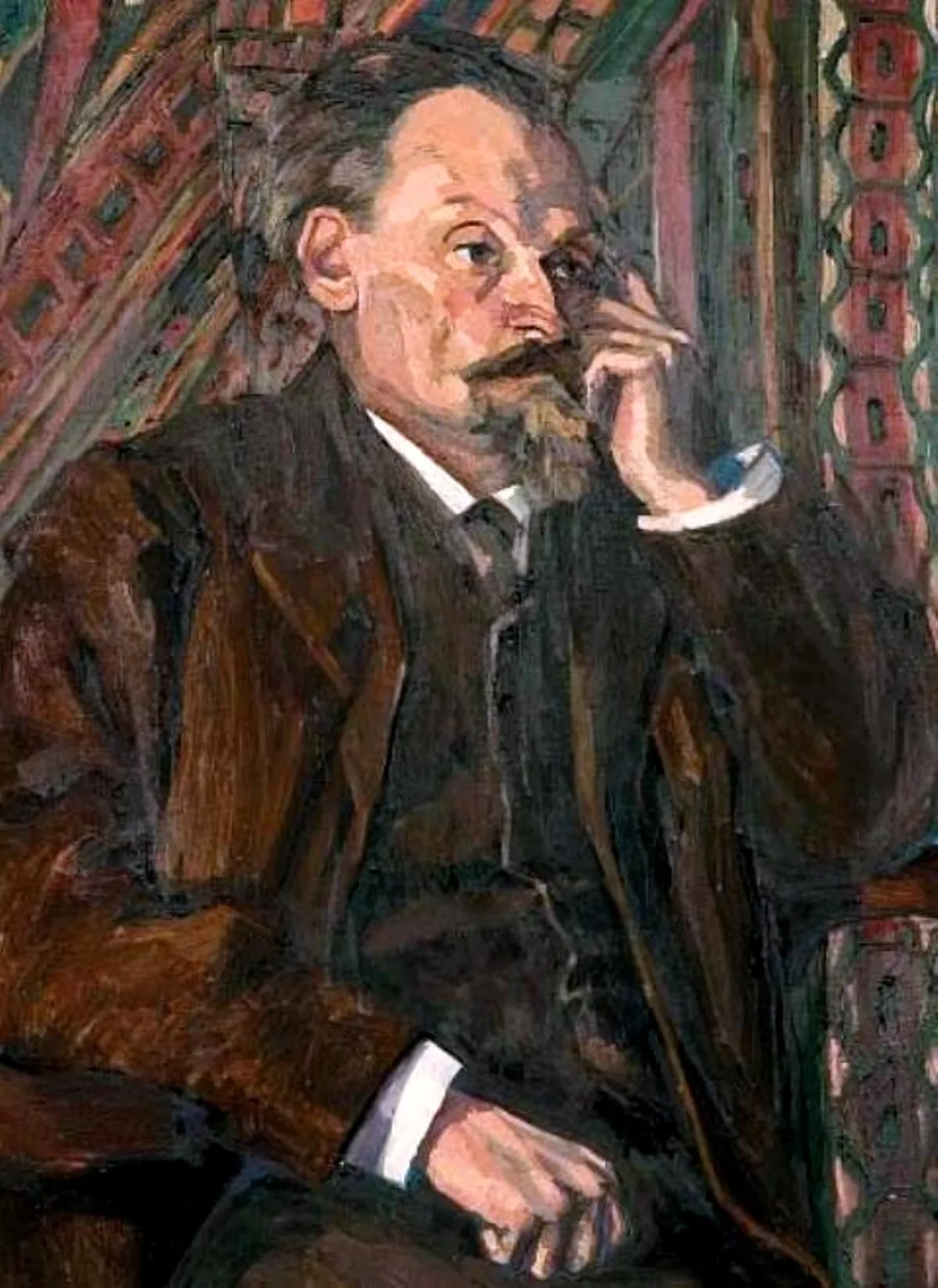

1. Zamfir Arbore was mostly active as an international anarchist and a disciple of Mikhail Bakunin, but eventually parted with the latter to create his independent group, the Revolutionary Community.

1.

1. Zamfir Arbore was mostly active as an international anarchist and a disciple of Mikhail Bakunin, but eventually parted with the latter to create his independent group, the Revolutionary Community.

Zamfir Arbore was close to the anarchist geographer Elisee Reclus, who became his new mentor.

Zamfir Arbore settled in Romania after 1877, and, abandoning anarchism altogether, committed himself to the more moderate cause of socialism.

Zamfir Arbore had by then earned academic credentials with his detailed works on Bessarabian geography, and, as a cultural journalist, cultivated relationships with socialist and National Liberal activists.

Zamfir Arbore was notoriously the friend of poet Mihai Eminescu in the 1880s, and worked closely with writer Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu during the 1890s.

Zamfir Arbore was survived by his two daughters, both of them famous in their own right: Ecaterina was a communist politician and physician; Nina a modern artist.

Zamfir Arbore inherited the Ralli family mansion, a Bessarabian manorial estate in Dolna, which in the 1820s had served as the Pushkin's vacation house.

Zamfir Arbore later moved into Bessarabia, attending school in Kishinev, before moving to another school in Nikolayev.

Unable to finish his studies, Zamfir Arbore was singled out for arrest, and according to his own account, since placed under doubt, even served time as a political prisoner in the Peter and Paul Fortress and in Siberia.

Zamfir Arbore corresponded with the latter for a significant period, sharing his interest in social geography.

Zamfir Arbore was, with philosopher Vasile Conta, one of the few intellectuals with a Romanian background to affiliate directly with the International Workingmen's Association, which regrouped the various Marxist and anarchist communities of Europe.

Zamfir Arbore's beliefs led him to join the Jura federation, an anarchist cell within the First International, and to become initiated into Freemasonry.

Zamfir Arbore was among those who established, in 1875, the Genevan Russian-language newspaper Rabotnik, which bridged the "young Bakuninist" faction with the Eser Party of Vera Figner and Reclus' St Imier International.

One of his colleagues there, future astronomer Nikolai Alexandrovich Morozov, recalled that Zamfir Arbore was actively involved in redacting news arriving from Russia, manipulating them for dramatic effect and political conformity.

Zamfir Arbore was by then married, to the Russian Ecaterina Hardina.

Zamfir Arbore's eldest child was daughter Ecaterina Arbore-Ralli, the future communist, feminist and militant physician, born on November 11,1873, at Bex.

Zamfir Arbore's son Dumitru was born on January 11,1877, in Geneva.

Zamfir Arbore first set foot in Romania during 1873, when he traveled from Geneva to Iasi, meeting with the young socialist sympathizer Eugen Lupu.

Zamfir Arbore was later in contact with the Iasi Marxist circle of Ioan, Iosif and Sofia Nadejde, sending them books by Karl Marx and his anarchist commentators.

Zamfir Arbore corresponded with some of the Russian socialists who had set up camp there, primarily so with Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea and Nicolae Zubcu-Codreanu.

In 1878, Zamfir Arbore was the editor of the international tribune of the Revolutionary Community, Obshchina, which was published as a successor of Rabotnik.

Reputedly threatened with an extradition back into the Russian Empire, Zamfir Arbore moved to Romania after the beginning of a Russo-Turkish War, during which the country, a Russian ally, obtained her independence from the Ottoman Empire.

Zamfir Arbore later recalled that the inspiration for this move was young Romanian leftist Mircea Rosetti, whom he had first met during Reclus' visit to Vevey.

Zamfir Arbore's connections were unsuccessful when it came to rescuing Dobrogeanu-Gherea, kidnapped and deported by the Russian Army in autumn 1877, although he eventually helped track down Gherea in Russia.

Three years later, when Dobrogeanu-Gherea escaped back to Romania, Zamfir Arbore helped him set up a restaurant in Ploiesti station, from which Gherea supported his family.

At the time, Zamfir Arbore was editor of Rosetti's democratic gazette Romanul, and later moved to a similar position with the left-leaning newspaper Telegraful Roman.

At this stage, Zamfir Arbore is believed to have helped other foreign-born socialists to find refuge in Romania: in particular to have assisted Peter Alexandrov, the brother-in-law of writer Vladimir Korolenko, in obtaining a license to practice medicine in Tulcea and in defending himself during subsequent police inquiries.

Zamfir Arbore was, around 1890, a correspondent for Frederic Dame's Bucharest newspaper La Liberte Roumaine, with expose pieces on the kidnapping of junior Bulgarian Navy officer Vladimir Kisimov by Russian spies.

Zamfir Arbore's third daughter Nina, later known as a visual artist, was born in January 1888.

Meanwhile, Zamfir Arbore was progressively integrated into the Romanian civil service: a clerk at the State Archives, he became a statistician in service to the Bucharest City Hall.

Zamfir Arbore followed up on his scholarly work with the 1904 Dictionar geografic al Basarabiei.

In 1906, during the National Exhibit held in celebration of the Romanian Kingdom, Arbore joined a scientific committee which supervised an academic inquiry into the state of Romanian peasants, whose main author was militant sociologist G D Scraba.

In 1904, Mikhail Nikolayevich von Giers, the Russian Ambassador to Romania, warned National Liberal Premier Dimitrie Sturdza that "Mr Ralli-Zamfir Arbore" intended to send into Russia many small packages of brochures, to be delivered by a special network of socialist agents.

Zamfir Arbore was singled out for extradition, but saved through the intercession of Take Ionescu, the Interior Minister, who even managed to have the weapons dispatched back to Romania.

Zamfir Arbore registered another personal triumph in 1905, when his aging friend Reclus traveled to Romania.

Together with Petru Cazacu, Zamfir Arbore founded and edited a newspaper named Basarabia, printed in Switzerland but clandestinely circulated the Russian Empire during the Revolution.

The text, signed Zemfir Ralli Zamfir Arbore, notably includes detail on Nechayev's isolated political outlook, which, Zamfir Arbore argued, was linked directly to 18th century Jacobin theorists and agitators rather than to later socialist schools.

The controversy drew attention from Romania's secret service, Siguranta Statului, whose agents suspected, probably without just cause, that Zamfir Arbore maintained contacts with Madan over the following period.

In June 1909, Constantin Mille's daily, Adevarul, printed a draft of Zamfir Arbore's memoirs, dealing with Eminescu's political views.

Zamfir Arbore did not join the Romanian Social Democratic Party, created by Rakovsky in 1910, but was a special guest at its reunions.

Zamfir Arbore was thus present at the PSDR's 1912 rally at Sala Dacia, where, in agreement with Rakovsky's political tenets, he spoke about the need to contain Russian imperialism; on the centenary of Bessarabia's occupation, he addressed Romanian student organizations, informing them about the state of affairs in Russian dominions.

Zamfir Arbore was claiming that some violent anarchists were in fact Russian agents: according to him, the suspected terrorist Ilie Catarau was a secret affiliate of the loyalist Black Hundreds.

In September 1914, Zamfir Arbore was honored by the PSDR's festive assembly honoring the 50th anniversary of the First International.

Zamfir Arbore's first-born daughter, who had by then made her first contributions to social medicine, became directly involved with the PSDR and the Romania Muncitoare club, and, in 1912, was elected to the PSDR Executive Committee.

In 1912, Zamfir Arbore translated and published for Minerva newspaper the 1886 manifesto "To the Romanian People", signed by Bulgarian revolutionary Zahari Stoyanov, in which Stoyanov spoke about his country's "moral duty" toward Romania and deplored the slow descent into ethnic rivalry.

Zamfir Arbore's stance was compatible with the PSDR's Zimmerwald neutralism: by 1915, Ecaterina Zamfir Arbore was noted for her political statements against a Russian alliance.

Suspicion arose that Zamfir Arbore was in the pay of German intelligence, receiving at least 28,000 lei through such channels.

In summer 1916, Romania disappointed Zamfir Arbore by rallying with the Entente.

Zamfir Arbore stayed behind in German-occupied Bucharest while the legitimate government withdrew to Iasi, and maintained a generally friendly but discreet attitude toward the occupiers.

Zamfir Arbore was less active as a journalist and militant, but contributed to the Germanophile daily Lumina, put out by the Bessarabian activist Constantin Stere, and once lectured on the Bessarabian question during April 1918.

Zamfir Arbore kept a low profile during the 1918 truce, when, with German acquiescence, Romania united with Bessarabia.

Zamfir Arbore further antagonized the public when, as a Communist Party of Romania founder, she supported the self-determination of Bessarabia and its separation from Romania, in line with Comintern policies.

Dumitru Zamfir Arbore joined the Communist Party, was kept under surveillance by the authorities for hosting conspirative sessions at his home in Prahova County, but remained in Romania, where he died in an October 1921 accident.

Zamfir Arbore lost his Senate seat when Parliament was dissolved by King Ferdinand I; he soon after left the Peasants' Party, pushed into opposition, and was reelected to the Senate as a People's Party candidate in the summer 1920 election.

In 1923, Zamfir Arbore published a new installment of his memoirs, as In temnitele rusesti.

Zamfir Arbore was still a contributor to the central leftist press: in December 1926, Adevarul published his piece about the Serbian politician Nikola Pasic, defunct leader of the People's Radical Party.

In 1930, the recently widowed Zamfir Arbore was pensioned from his teaching position at the Bucharest War School, where he had been lecturing in Geography and Topography.

Zamfir Arbore died in Bucharest, on April 2 or April 3,1933.

Zamfir Arbore was buried at Sfanta Vineri Cemetery, alongside Ecaterina, Dumitru, and Lolica Arbore.

Critic and political historian Ioan Stanomir writes that Zamfir Arbore, "the agent who precipitates revolution", was "an aristocrat animated by dramatic self-loathing".

Zamfir Arbore notably inventoried the villages originally settled by free peasants, accounting for 151 such localities in central Bessarabia and 4 in the Budjak.

However, as early as 1912, Zamfir Arbore was envisaging a general rising against Russia, involving the Poles and the Finns.

Zamfir Arbore therefore saw the Transylvanian union as a hopeless project; his consolation for Romanians, Transylvanian as well as Bukovinian, was in the federalization of Austria-Hungary.

Zamfir Arbore was more outspoken during the interwar period: his December 1918 speech demanded the guarantee of minority rights in Greater Romania, saluted the policies of Soviet Russia as a liberating force, and predicted a Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War.

Zamfir Arbore's works were reprinted in Moldova, the independent post-Soviet republic comprising the bulk of historical Bessarabia.

Zamfir Arbore's name was assigned to streets in both Chisinau and Bucharest.

Zamfir Arbore's contribution made an impact outside its immediate cultural context.

Zamfir Arbore's memoirs were reviewed early on by anarchist historian Max Nettlau, who called them inaccurate, without specifying to what extent.